Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Hunminjeongeum Haerye

1446 Korean text on Hangul From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

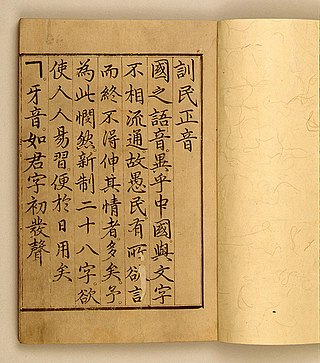

Hunminjeongeum Haerye (Korean: 훈민정음 해례; Hanja: 訓民正音解例), or simply Haerye, refers to either a commentary section on the text Hunminjeongeum or to copies of the Hunminjeongeum that contain the commentary section.[1] The Hunminjeongeum and commentary were published together as a single text around October 1446 (Gregorian calendar). Together, they introduce the native Korean alphabet Hangul.

The Joseon king Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450) authored the preface to the overall text as well as the basic introduction of the letters. The following members of the government agency Hall of Worthies coauthored the Haerye section: Chŏng Inji, Ch'oe Hang, Pak P'aengnyŏn, Sin Sukchu, Sŏng Sammun, Kang Hŭian, Yi Kae, and Yi Sŏllo. The text's postface was written by Chŏng Inji.[2] The commentary and postface describe how the shapes of Hangul's letters were derived.

The base Hunminjeongeum was republished separately from the Haerye on a number of occasions and consistently remained in the historical record. However, the Haerye section was eventually lost and forgotten, possibly by the early 16th century. A copy of the full Hunminjeongeum Haerye text was only rediscovered in 1940. Its rediscovery revolutionized scholarship on Hangul. As it is now in the collection of Kansong Art Museum, it is known as the "Kansong copy". A second copy, the "Sangju copy", was discovered in 2008, although its discoverer has continually refused to show much of it to others. The South Korean government agency Korea Heritage Service was ruled the legal owner of that copy in 2019. A number of police raids to seize the copy from the discoverer have failed.

The Kansong copy of the Haerye was designated a National Treasure of South Korea in 1962 and entered into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1997.

Remove ads

Publication date

An exact publication date for the work is not known. The base Hunminjeongeum claims to have been published in the 9th month of 1446 (Korean calendar). The postface to the Haerye is dated to the first ten days (상한; 上澣) of that month; it does not specify which day in that range the postface was completed. If the 10th day is assumed, that is October 9 in the Gregorian calendar; that day is celebrated as Hangul Day in South Korea.[3][4]

Remove ads

Contents

The Hunminjeongeum Haerye edition consists of two main parts: the base Hunminjeongeum and the Haerye. The Haerye has six sections. Several sections of the Haerye are written in seven-syllable lines in irregular rhyme.[a][6] The sections are:[7][8]

- "Explanation of the Design of the Letters" (제자해; 制字解)

- "An Explanation of the Initials" (초성해; 初聲解)

- "An Explanation of the Medials" (중성해; 中聲解)

- "An Explanation of the Finals" (종성해; 終聲解)

- "An Explanation of the Combination of the Letters" (합자해; 合字解)

- "Examples of the Uses of the Letters" (용자례; 用字例)

Remove ads

History

The base Hunminjeongeum was published separately from the Haerye on a number of different occasions and consistently remained in the historical record. By contrast, the Haerye was eventually lost and forgotten, possibly by the early 16th century.[10]

Kansong copy

Summarize

Perspective

In 1940, a copy of the Haerye was rediscovered.[11] It has since become part of the collection of Kansong Art Museum.[12] Its rediscovery dramatically altered scholarship on Hangul, especially as its explanations on the derivations of the shapes of the letters had been forgotten.[10] It is widely believed to largely be an authentic original copy from 1446, although some scholars challenge that assumption.[13] For example, according to Ledyard, linguist Pang Chonghyŏn argued that, while he believed the copy was authentic, it was not an original from the time of Sejong, and was instead produced some time before the 1592–1598 Imjin War.[14]

The copy had been held by the family of Yi Han'gŏl (이한걸; 李漢杰) in Andong.[15] It was claimed that the copy had been gifted to an ancestor of Yi (it is unclear which) by Sejong himself. Another claim was that, during the reign of Yeonsangun (r. 1495–1506), Hangul texts were sought out and destroyed; to preserve the text, the cover and first two leaves were destroyed to make the text harder to identify.[16]

In summer of 1940, one of Yi's sons Yongjun (이용준) informed a teacher of his[b] of the text's existence.[18] This information reached art collector Jeon Hyeong-pil (1906–1962), who expressed interest in purchasing it.[19]

Forged pages and cover

Although the rest of the text was in relatively good condition with the exception of the edges of some early pages,[19] Yi Yongjun apparently feared that the destroyed portions would ruin the text's value. He secretly attempted to restore it, in a manner that Ledyard described as "inept and malicious". Jeon reportedly instantly recognized that the work had been doctored; in order to spare the Yi family the embarrassment, he purchased it and agreed to not reveal where he acquired the text from.[20]

A tracing of the transcription soon reached the academic community. A moveable type edition was first published in 1940.[c] In 1943, newspaper The Chosun Ilbo published the text in full. It was only in October 1946 that a direct reproduction of the text was published by the Korean Language Society. In July 1957, Tongmungwan released a new photoprint edition. Both the Korean Language Society and Tongmungwan prints were widely referred to for long afterwards, although Ahn was critical of aspects of both of them.[22]

The truth of the forgery was gradually revealed, with scholars increasingly identifying flaws over time.[23] Scholars assume that the forgers relied on other Eonhae and Veritable Records versions of the Hunminjeongeum.[16]

Flaws in the forgery and cover include:

- The title for the work was lost; the restorer merely gives it as Hunminjeongeum, but Ahn argued that it should be Eoje hunminjeongeum (어제 훈민정음; 御製訓民正音; Ŏje hunminjŏngŭm), where eoje means "by His Majesty". It was convention during the Joseon period to attach that phrase to works produced by monarchs.[24]

- The forged leaves were boiled to make them appear older.[20]

- Tone markings are missing on the restored pages.[25]

- Restored pages have punctuation marks in a different style, with some mistakes.[26]

- The final character of Sejong's preface is mistakenly given as 矣 instead of 耳.[27]

- It was recut to be a little smaller than its original size.[d][29] The book's size is currently 29.3 cm × 20.1 cm (11.5 in × 7.9 in).[30]

Description

It currently has a silk cover in front and back; recent additions. It has oversewn binding in four-needle stitches. It was rebound in the 20th century, after it entered Jeon's possession. It is unknown what the previous binding method was; it was likely the common practice in Korea, which was five-needle stitching.[31] In total, there are 33 leaves in the work, with the Yeui occupying 4 and the Haerye the rest. Each body page in Yeui has seven lines with space for 11 characters each. Each page in the Haerye has eight lines with space for 13 characters each.[30]

The style of the Haerye differs from that of the Hunminjeongeum. For example, the Hunminjeongeum is written in a larger square printed style compared to the smaller square running style of the Haerye.[29] Ahn argues the differing style is because it was convention to make the king's writing distinguishable in print from that of his subjects.[32] It is generally believed that the calligraphy of both portions were by a single person intentionally using different styles: Grand Prince Anp'yŏng, one of Sejong's sons and a famed calligrapher.[33]

This edition was designated a National Treasure of South Korea on December 20, 1962[34][35] and a UNESCO Memory of the World in 1997.[36][37]

Remove ads

Sangju copy

Summarize

Perspective

History

On July 28, 2008, book dealer Bae Ik-gi (배익기) announced that he discovered that he was in possession of another copy of the Hunminjeongeum Haerye.[39] Bae revealed only a limited number of pages of the work to the public and to researchers, and otherwise refused to show it, as he sought a financial reward for it.[40]

On August 1, Jo Yeong-hun (조영훈) announced that the copy belonged to him, and that it had been stolen from him. According to Jo, the copy had been lying around in his bookstore and Bae took it without paying whilst purchasing boxes of other books. Jo filed criminal complaints against Bae that were dismissed. Jo then filed a lawsuit against Bae on February 5, 2010. On May 13, 2011, the Supreme Court of Korea ruled that Bae had indeed stolen it, and ordered Bae to return it to Jo. Bae refused. Jo filed a criminal report against Bae on July 5. Police conducted three raids on Bae's properties on August 30, but failed to locate the copy.[39]

An investigation by prosecutors found that the copy had originally been stored within a Buddhist statue at the temple Gwangheungsa (광흥사) in Andong, South Korea until it was stolen in 1999. The prosecution obtained a confession from the thief who took it and sold it to Jo. Bae was then arrested. On February 9, 2012, Bae was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison.[39] In May, Jo pledged to donate the copy to the government agency Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA).[41][39] On September 7, the Daegu High Court overturned Bae's conviction of theft on grounds of insufficient evidence. However, Bae continued to refuse to turn over the copy and kept it hidden. Jo died on December 26, 2012. Bae's acquittal was affirmed by the Supreme Court on May 29, 2014.[39]

On March 26, 2015, a fire destroyed Bae's home within 30 minutes.[e] Concerns were raised that the copy could have been destroyed.[39] In 2015, Bae shared a photo of the book, which had been partially charred by the fire.[43][44]

In 2015, Bae began offering to sell the copy for ₩100 billion (US$90 million).[39] This price was chosen based on an assessment by the CHA of the copy's value at over ₩1 trillion (US$900 million).[39][40] In 2017, he ran in a local election; he promised to share the work if he won, but he lost.[44] While doing so, Bae declared his assets as ₩1.48 trillion, in reflection of the work's assessed value.[43] Bae alleged that the price was fair, considering the value of the work, and claimed that the previous legal battles, as well as what he alleged was a smear campaign by CHA against him, had significantly negatively impacted him.[39][40] The CHA refuses to pay the amount, as it is illegal to purchase cultural assets considered stolen.[43] The CHA has also been reluctant to try and take the copy by force, in fear that Bae would destroy it in retaliation.[45]

In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that, while there was insufficient evidence to show that Bae had stolen the copy, the state was the copy's rightful owner.[46] Still, Bae refused to turn over the copy. The CHA held numerous meetings with Bae over the years to negotiate the copy's return, but Bae continually refused.[47] In 2019, a group of school children met with Bae to ask him to return the book, but he again refused.[48] In 2022, a raid on Bae's office failed to retrieve the copy.[47][43]

Bae has received significant criticism from the public.[43] According to a 2024 report, he has been isolating himself from his local community.[48]

Description

Only limited parts of the book have been seen by the public.[49] Scholar Nam Kwonhui believes the book to be an original first-edition copy that dates to the 15th-century.[41] It is possibly missing an undetermined number of pages; Kim and Nam claimer in 2014 that only pages after the 9th leaf have been attested to, meaning that the base Hunminjeongeum is not attested to. They also claim leaves 15 to 25 and 29 (containing Chŏng's postface) have not been attested to. Various pages contain brush-written notes in the margins.[50] Kim and Nam believe these notes to date the 18th century.[51]

It is made of traditional Korean paper (mulberry). It has a cover that appears newer and possibly dates to the 16th and 17th centuries. It was possibly rebound from 4-hole to 5-hole stitching.[52] The title of the work is given as Osŏngjejago (오성제자고; 五聲制字攷; lit. Investigation of the Five Classes of Sounds and Design of the Letters). This title was possibly given by whoever rebound the book, and is possibly a mistake.[53] Based on the limited pictures and videos, it is believed that the Sangju copy was printed with the same wood blocks as the Kansong copy.[54]

Remove ads

Notes

- Teacher was Kim T'aejun (김태준), school was Kyŏnghagwŏn, a Confucianist school and predecessor to Sungkyunkwan University.[17]

- Published in volume 35 of the journal Chŏngŭm (정음), then in the book Han'gŭlgal (한글갈) by Choe Hyeon-bae.[21]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads