Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ico

2001 video game From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Ico[b] (/ˈiːkoʊ/ EE-koh) is a 2001 action-adventure game developed and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation 2. It was designed and directed by Fumito Ueda, who wanted to create a minimalist game based on a "boy meets girl" concept. Originally planned for the PlayStation, Ico took approximately four years to develop. The team employed a "subtracting design" approach to reduce gameplay elements that interfered with the game's setting and story in order to create immersion.

This article or section is undergoing significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are actively editing this article or section, you can replace this template with {{in use|5 minutes}}.

This article was last edited by Harizotoh9 (talk | contribs) 2 days ago. (Update timer) |

The player controls Ico, a boy born with horns, which his village considers a bad omen. After warriors lock him in an abandoned castle, he frees Yorda, the daughter of the castle's Queen, who plans to use Yorda to extend her life. Ico must work with Yorda to escape the castle while protecting her from enemies, assisting her across obstacles, and solving puzzles.

Ico introduced several design and technical elements that have influenced subsequent games, including a story told with minimal dialogue, bloom lighting, and key frame animation. Although not a commercial success, it was acclaimed for its art, original gameplay and story elements. It received several awards, including "Game of the Year" nominations and three Game Developers Choice Awards. Considered a cult classic, it has been called one of the greatest video games ever made, and is often brought up in discussions about video games as an art form. In 2006, it was re-released in Europe alongside Shadow of the Colossus, the spiritual successor to Ico. A high-definition remaster of the game was included in The Ico & Shadow of the Colossus Collection for the PlayStation 3.

Remove ads

Gameplay

Summarize

Perspective

Ico is primarily a three-dimensional platform game. The player controls Ico from a third-person perspective as he explores the castle and attempts to escape it with Yorda.[3] The camera is fixed but swivels to follow Ico or Yorda as they move; the player can also pan the view a small degree in other directions to observe more of the surroundings.[4] The game includes many elements of platform games; for example, the player must have Ico jump, climb, push, and pull objects. The player must also perform other tasks such as solving puzzles in order to progress within the castle.[5]

Only Ico can carry out these actions; Yorda can only jump short distances and cannot climb over tall barriers. The player must use Ico to help Yorda cross obstacles, such as by lifting her to a higher ledge, or by arranging the environment to allow Yorda to cross a larger gap herself. The player can tell Yorda to follow Ico, or to wait at a particular spot. The player can have Ico take Yorda's hand and pull her along at a faster pace across the environment.[6] The player cannot progress until they move Yorda to certain doors that only she can open.[3]

Escaping the castle is made difficult by shadow creatures sent by the Queen. These creatures attempt to drag Yorda into black vortexes if Ico leaves her for any length of time, or if she is in certain areas of the castle. Ico can dispel these shadows using a stick or sword, as well as free Yorda if she is drawn into a vortex.[3] While the shadow creatures cannot harm Ico, the game is over if Yorda becomes fully engulfed in a vortex; the player must then restart from a save point. The player will also restart from a save point if Ico falls from a large height. Save points in the game are represented by stone benches that Ico and Yorda rest on as the player saves the game.[6] In the European and Japanese releases, upon completion of the game, the player can restart the game in a local co-operative two-player mode; the second player plays as Yorda, under the same limitations as the computer-controlled version of the character. The new game mode also adds subtitles that translate Yorda's fictional language.[7][8]

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Ico, a horned boy, is taken by a group of warriors to an abandoned castle and locked inside a stone coffin to be sacrificed.[9] A tremor topples the coffin and Ico escapes. As he searches the castle, he meets Yorda, a captive girl who speaks a different language. Yorda is magically linked to the castle and has the ability to open various gates using white energy that emanates from her body. However, she is physically incapable of defending herself. Ico helps Yorda escape and defends her from shadow-like creatures. The pair make their way through the castle and arrive at the bridge leading to land. As they cross, the Queen – ruler of the castle – appears and tells Yorda that she cannot leave the castle.[10] Later, as they try to escape, the bridge splits and they get separated; Yorda tries to save Ico but the Queen prevents it. He falls off the bridge and loses consciousness.

Ico awakens below the castle and makes his way back to the upper levels, finding a magic sword that dispels the shadow creatures. After discovering that Yorda has been turned to stone by the Queen, he confronts her, who reveals that she plans to possess Yorda's body.[11] Ico slays the Queen with the sword, but his horns are broken in the fight and loses consciousness afterwards. The castle begins to collapse around Ico, but the Queen's spell on Yorda is broken, and a shadowy Yorda carries Ico safely out of the castle to a boat, sending him to drift to the shore alone. She says "Nonomori" (translating to "good bye") to Ico as he drifts away from the castle.[8]

Ico awakens on a beach shore to find the distant castle in ruins, and Yorda – in her human form – washed up nearby.[4] She wakes up and smiles at Ico.

Remove ads

Development

Summarize

Perspective

Lead designer Fumito Ueda came up with the concept for Ico in 1997, envisioning a "boy meets girl" story where the two main characters would hold hands during their adventure, forming a bond between them without communication.[4] Ueda's original inspiration for Ico was a TV commercial he saw, which depicted a woman holding the hand of a child while walking through the woods. He was also inspired by the manga series Galaxy Express 999, where a woman protects a young boy as they travel through the galaxy, which he considered adapting into a new idea for video games.[13] He also cited his work as an animator on Kenji Eno's Sega Saturn game Enemy Zero, which influenced Ico's animation, cutscenes, lighting effects, sound design, and mature appeal.[14] Ueda was also inspired by the video game Another World (Outer World in Japan), which used cinematic cutscenes, lacked any head-up display elements as to play like a movie, and also featured an emotional connection between two characters despite the use of minimal dialog.[15][16][17] He also cited Sega Mega Drive games,[18] Virtua Fighter,[19] Lemmings, Flashback, and the original Prince of Persia games as influences, specifically regarding animation and gameplay style.[15][17] With the help of an assistant, Ueda created an animation in Lightwave to better convey his vision.[4] In the three-minute demonstration reel, Yorda had the horns instead of Ico, and flying robotic creatures were seen firing weapons at the castle.[4][20] Ueda stated that having this movie that represented his vision helped to keep the team on track during development. He reused this technique for the development of Shadow of the Colossus, the team's next project.[4][21]

Ueda, at the time an employee at Sony Computer Entertainment Japan, began working with producer Kenji Kaido in 1998 to develop the idea and bring the game to the PlayStation. He was granted his own unit as the studio primarily assisted on games from other Japanese developers.[22] Ueda also brought in a number of people outside the video game industry to help with development. These consisted of two programmers, four artists, and one designer in addition to Ueda and Kaido.[4][22]

Ico's design aesthetics were guided by three key notions: to make a game that would be different from others in the genre, feature an aesthetic style that would be consistently artistic, and have an imaginary yet realistic setting.[4] This was achieved through the use of "subtracting design"; elements which interfered with the game's immersion were removed.[4] This included removing any form of interface elements, keeping the gameplay focused only on escaping the castle, and having a single enemy type. Ueda commented that he purposely tried to distance Ico from conventional video games due to the negative image video games were receiving at that time, in order to draw more people to the title.[23]

An interim design of the game shows Ico and Yorda facing horned warriors similar to those who take Ico to the castle. The game originally focused on returning Yorda to her room in the castle after she was kidnapped by these warriors.[20] Ueda believed this version was too detailed for the graphics engine they had developed and, as part of the "subtracting design", replaced the warriors with the shadow creatures.[4] On reflection, Ueda noted that the subtracting design may have taken too much out of the game, and did not go to as great an extreme with Shadow of the Colossus.[4]

After two years of development, the team ran into limitations on PlayStation hardware and faced a critical choice: either terminate the project altogether, alter their vision to fit the constraints of the hardware, or continue to explore more options. The team decided to remain true to Ueda's vision, and began to use the PlayStation 2's Emotion Engine, taking advantage of the improved abilities of the platform.[24][25] Character animation was accomplished through key frame animation instead of the more common motion capture technique.[26] The game took about four years to develop.[4] Ueda intentionally left the ending vague, not stating whether Yorda was alive, whether she would travel with Ico, or if it was simply the protagonist's dream.[4]

Ico uses minimal dialogue in a fictional language to provide the story throughout the game.[3] Voice actors included Kazuhiro Shindō as Ico, Rieko Takahashi as Yorda, and Misa Watanabe as the Queen.[27] Ico and the Queen's words are presented in either English or Japanese subtitles depending on the release region, but Yorda's speech is presented in a symbolic language.[3] This symbolic language consists of 26 runic letters which correspond to the Latin alphabet, and the script was designed by team member Kei Kuwabara.[28] Ueda opted not to provide the translation for Yorda's words as it would have overcome the language barrier between Ico and Yorda, and detracted from the "holding hands" concept of the game.[4] The game initially had 115 lines of spoken dialogue; however, 77 of these lines were not used in the final game, and can only be accessed via data-mining.[29]

Remove ads

Release

Summarize

Perspective

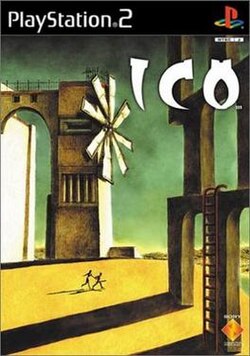

The game was released in Japan on December 6, 2001 alongside Yoake no Mariko, developed by another unit of Sony as a collaboration with Spümcø.[31] The cover is inspired by the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico and his work The Nostalgia of the Infinite; Ueda believed that "the surrealistic world of de Chirico matched the allegoric world of Ico".[32] It was used for the releases in Japan and PAL regions. The North American version was released two months earlier; due to time constraints, it lacks the cover art intended by Ueda, as well as additional features such as the two-player mode.[33][34] The North American cover has been considered one of the worst video game covers in contrast to the game's quality.[35][30] On reflection, Yasuhide Kobayashi, vice-president of Sony's Japan division, believed the North American box art and lack of an identifiable English title led to the game's poor sales in the United States, and stated plans to correct that for the release of The Last Guardian.[36]

In PAL regions, a limited edition of the game was available; this included a cardboard wrapping displaying artwork from the game and four art cards inside the box.[37] In 2006, the game was re-released across all PAL regions (except France) following the release of Shadow of the Colossus, Ico's spiritual sequel, to allow players to "fill the gap in their collection".[38]

Despite the positive reception by critics, Ico did not sell well. By 2009, only 700,000 copies had been sold worldwide, with 270,000 in the United States,[36] and the bulk in PAL regions.[22] Ueda considered his design by subtraction approach may have hurt the marketing of the game, as at the time of the game's release, promotion of video games were primarily done through screenshots; since Ico lacked any heads-up display, it appeared uninteresting to potential buyers.[39]

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Reception

Ico received acclaim from players and critics, with an aggregated review score of 90 out of 100 at Metacritic.[40] The game has gained a cult following,[49] and is considered by some to be one of the greatest games of all time; Edge ranked Ico as the 13th top game in a 2007 listing,[50] while IGN ranked the game at number 18 in 2005,[51] and at number 57 in 2007.[52] Ico has been used as an example of a game that is a work of art.[53][54][55]

Some reviewers have likened Ico to older, simpler adventure games such as Prince of Persia or Tomb Raider, that seek to evoke an emotional experience from the player;[42][53] IGN's David Smith commented that while simple, as an experience the game was "near indescribable".[56] Critics praised the game's graphics and sound design; Smith continues that "The visuals, sound, and original puzzle design come together to make something that is almost, if not quite, completely unlike anything else on the market, and feels wonderful because of it."[56] Many reviewers were impressed with the expansiveness and the details given to the environments, the animation used for the main characters despite their low polygon count, and the use of lighting effects.[3][5][56] Ico's ambiance, created by the simple music and the small attention to detail in the voice work of the main characters, were also called out as strong points for the game. Charles Herold of The New York Times summed up his review stating that "Ico is not a perfect game, but it is a game of perfect moments."[26] Herold later commented that Ico breaks the mold of games that usually involve companions. In most games these companions are invulnerable and players will generally not concern with the non-playable characters' fate, but Ico creates the sense of "trust and childish fragility" around Yorda, which leads to the character being "the game's entire focus".[57]

The game is noted for its simple combat system that would "disappoint those craving sheer mechanical depth", as stated by GameSpot's Miguel Lopez.[5] The game's puzzle design has been praised for creating a rewarding experience for players who work through challenges on their own;[56] Kristen Reed of Eurogamer, for example, said that "you quietly, logically, willingly proceed, and the illusion is perfect: the game never tells you what to do, even though the game is always telling you what to do".[6] Ico is also considered a short game, taking between seven and ten hours for a single play through, which GameRevolution calls "painfully short" with "no replay outside of self-imposed challenges".[45] G4TV's Matthew Keil, however, felt that "the game is so strong, many will finish 'Ico' in one or two sittings".[3] The lack of features in the North American release, which would become unlocked on subsequent playthroughs after completing the game, was said to reduce the replay value of the title.[3][56] Electronic Gaming Monthly notes that "Yorda would probably be the worst companion -she's scatterbrained and helpless; if not for the fact that the player develops a bond with her, making the game's ending all the more heartrending."[58]

Francesca Reyes reviewed the game for Next Generation, rating it four stars out of five, and stated that "Intensely involving and wonderfully simple, Ico, though flawed, deserves to find its niche as a quiet classic."[48]

Awards

Ico received several acclamations from the video game press, and was considered to be one of the Games of the Year by many publications, despite competing with releases such as Halo: Combat Evolved, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, and Grand Theft Auto III.[52] The game received three Game Developers Choice Awards in 2002, including "Excellence in Level Design", "Excellence in Visual Arts", and "Game Innovation Spotlight".[59] The game won two Interactive Achievement Awards from the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences in 2002 for outstanding achievement in "Art Direction" and "Character or Story Development"; it also received nominations for "Game of the Year", "Console Game of the Year", "Console Action/Adventure Game of the Year", "Innovation in Console Gaming", and outstanding achievement in "Game Design" and "Sound Design".[60] It won GameSpot's annual "Best Graphics, Artistic" prize among console games.[61] It was one of three titles to win the Special Award at the sixth CESA Game Awards.[62][63]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Ico influenced numerous other video games, which borrowed from its simple and visual design ideals.[39] Several game designers, such as Eiji Aonuma, Hideo Kojima, and Jordan Mechner, have cited Ico as having influenced the visual appearance of their games, including The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, respectively.[22] Marc Laidlaw, scriptwriter for the Half-Life series, commented that, among several other more memorable moments in the game, the point where Yorda attempts to save Ico from falling off the damaged bridge was "a significant event not only for that game, but for the art of game design".[64] The Naughty Dog team used Ico as part of the inspiration for developing Uncharted 3.[39] Vander Caballero credits Ico for inspiring the gameplay of Papo & Yo.[65] Phil Fish used the design by subtraction approach in developing the title Fez.[39] The developers of both Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons and Rime have Ico as a core influence on their design.[39] Hidetaka Miyazaki, creator and director of the Dark Souls series, cited Ico as a key influence to him becoming involved in developing video games, stating that Ico "awoke me to the possibilities of the medium".[66] Goichi Suda aka Suda51, said that Ico's save game method, where the player has Ico and Yorda sit on a bench to save the game, inspired the save game method in No More Heroes where the player-character sits on a toilet to save the game.[67]

Ico was one of the first video games to use a bloom lighting effect, which later became a popular effect in video games.[1] Patrice Désilets, creator of Ubisoft games such as Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Assassin's Creed, cited Ico as an influence on the game design of The Sands of Time.[68][69] Jenova Chen, creator of art games such as Flower and Journey, cited Ico as one of his biggest influences.[70] Ico was also cited as an influence by Halo 4 creative director Josh Holmes.[39] Naughty Dog said The Last of Us was influenced by Ico, particularly in terms of character building and interaction,[71] and Neil Druckmann credited the gameplay of Ico as a key inspiration when he began developing the story of The Last of Us.[72][73]

Film director Guillermo del Toro cited both Ico and Shadow of the Colossus as "masterpieces" and part of his directorial influence.[74] Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead considers it one of his top ten video games of all time, saying it "might be the best one".[75][76]

Related media

Ico's audio featured a limited amount of music and sound effects. The soundtrack, Ico: Kiri no Naka no Senritsu (ICO~霧の中の旋律~, Iko Kiri no Naka no Senritsu; lit. "Ico: Melody in the mist"), was composed by Michiru Oshima and sound unit "pentagon" (Koichi Yamazaki & Mitsukuni Murayama) and released in Japan by Sony Music Entertainment on February 20, 2002. The album was distributed by Sony Music Entertainment Visual Works. The last song of the CD, "ICO -You Were There-", includes vocals sung by former Libera member Steven Geraghty.[77][78]

A novelization of the game titled Ico: Kiri no Shiro (ICO-霧の城-, Iko: Kiri no Shiro; lit. 'Ico: Castle of Mist') was released in Japan in 2004.[79] Author Miyuki Miyabe wrote the novel because of her appreciation of the game.[80] A Korean translation of the novel, entitled 이코 – 안개의 성 (I-ko: An-gae-eui Seong) came out the following year, by Hwangmae Publishers,[81] while an English translation was published by Viz Media on August 16, 2011.[82]

On June 11th, 2009, costumes (including Ico and Yorda), stickers, and sound effects from Ico were released as part of a paid downloadable add-on pack for the game LittleBigPlanet, titled Team Ico, which was available for download as DLC on the PlayStation Network store alongside similar materials from Shadow of the Colossus, after being teased by the game's developers Media Molecule about two weeks prior.[83][84][85] Ico makes cameo appearances in Astro's Playroom and Astro Bot, Yorda also appearing in the latter.[86][87]

Other Team Ico games

Shadow of the Colossus was developed by the same team and released for the PlayStation 2 in 2005. The game features similar graphics, gameplay, and storytelling elements as Ico. The game was referred by its working title "Nico" ("Ni" being Japanese for the number 2") until the final title was revealed.[88] Ueda, when asked about the connection between the two games, stated that Shadow of the Colossus is a prequel to Ico.[23]

The team's third game, The Last Guardian, was announced for the PlayStation 3 at E3 2009. The game centers on the connection between a young boy and a large griffin-like creature that he befriends, requiring the player to cooperate with the creature to solve the game's puzzles. The game fell into development hell due to hardware limitations and the departure of Ueda from Sony around 2012, along with other Team Ico members, though Ueda and the other members continued to work on the game via consulting contracts. Development subsequently switched to the PlayStation 4 in 2012, and the game was reannounced in 2015 and released in December 2016.[89][90] Ueda has said that "the essence of the game is rather close to Ico".[91]

HD remaster

Ico, along with Shadow of the Colossus, received a high-definition remaster for the PlayStation 3 that was released worldwide in September 2011. In addition to improved graphics, the games were updated to include support for stereoscopic 3D and PlayStation Trophies. The Ico port was also based on the European version, and includes features such as Yorda's translation and the two-player mode.[92] In North America and Europe/PAL regions, the two games were released as a single retail collection,[93] while in Japan, they were released as separate titles.[94] Both games have since been released separately as downloadable titles on the PlayStation Network store.[95] Patch 1.01 for the digital high-definition Ico version added the Remote Play feature, allowing the game to be played on the PlayStation Vita.[96]

Remove ads

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads