Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Island gigantism

Biological phenomenon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

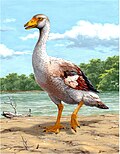

Island gigantism, or insular gigantism, is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. Island gigantism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies, and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies (insular dwarfism). This is itself one aspect of the more general phenomenon of island syndrome which describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular (island) species compared to their continental counterparts. Following the arrival of humans and associated introduced predators (dogs, cats, rats, pigs), many giant as well as other island endemics have become extinct (e.g. the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire, giant flightless pigeons related to the Nicobar pigeon). A similar size increase, as well as increased woodiness, has been observed in some insular plants such as the Mapou tree (Cyphostemma mappia) in Mauritius which is also known as the "Mauritian baobab" although it is member of the grape family (Vitaceae).

Remove ads

Possible causes

Summarize

Perspective

Large mammalian carnivores are often absent on islands because of insufficient range or difficulties in over-water dispersal. In their absence, the ecological niches for large predators may be occupied by birds, reptiles or smaller carnivorans, which can then grow to larger-than-normal size. For example, on prehistoric Gargano Island in the Miocene-Pliocene Mediterranean, on islands in the Caribbean like Cuba, and on Madagascar and New Zealand, some or all apex predators were birds like eagles, falcons and owls, including some of the largest known examples of these groups. However, birds and reptiles generally make less efficient large predators than advanced carnivorans.

Since small size usually makes it easier for herbivores to escape or hide from predators, the decreased predation pressure on islands can allow them to grow larger.[1][a] Small herbivores may also benefit from the absence of competition from missing types of large herbivores.

Benefits of large size that have been suggested for island tortoises include decreased vulnerability to scarcity of food and/or water, through ability to survive for longer intervals without them, or ability to travel longer distances to obtain them. Periods of such scarcity may be a greater threat on oceanic islands than on the mainland.[4]

Thus, island gigantism is usually an evolutionary trend resulting from the removal of constraints on the size of small animals related to predation and/or competition.[5] Such constraints can operate differently depending on the size of the animal, however; for example, while small herbivores may escape predation by hiding, large herbivores may deter predators by intimidation. As a result, the complementary phenomenon of island dwarfism can also result from the removal of constraints related to predation and/or competition on the size of large herbivores.[6] In contrast, insular dwarfism among predators more commonly results from the imposition of constraints associated with the limited prey resources available on islands.[6] As opposed to island dwarfism, island gigantism is found in most major vertebrate groups and in invertebrates.

Territorialism may favor the evolution of island gigantism. A study on Anaho Island in Nevada determined that reptile species that were territorial tended to be larger on the island compared to the mainland, particularly in the smaller species. In territorial species, larger size makes individuals better able to compete to defend their territory. This gives additional impetus to evolution toward larger size in an insular population.[7]

A further means of establishing island gigantism may be a founder effect operative when larger members of a mainland population are superior in their ability to colonize islands.[8]

Island size plays a role in determining the extent of gigantism. Smaller islands generally accelerate the rate of evolution of changes in organism size, and organisms there evolve greater extremes in size.[9]

Remove ads

Examples

Summarize

Perspective

Examples of island gigantism include the Galapagos giant tortoise, Komodo dragons, and the Flores giant rat.

Mammals

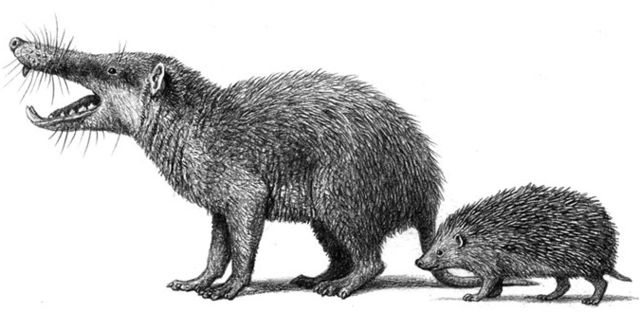

Many rodents grow larger on islands, whereas carnivorans, proboscideans and artiodactyls usually become smaller.

Eulipotyphlans

Rodents

Lagomorphs

Primates

Carnivorans

Gondwanatherians

Birds

Stem birds

Ratites

Waterfowl

Pangalliformes

Gruiformes

Pigeons

Birds of prey

Parrots

Owls

Caprimulgiformes

Passeriforms

Reptiles

Iguanids

Geckos

Skinks

Wall lizards

Snakes

Dubious examples

- The Komodo dragon of Flores and nearby islands, the largest extant lizard, and a similar (extinct) giant monitor lizard from Timor have been regarded as examples of giant insular carnivores. Since islands tend to offer limited food and territory, their mammalian carnivores (if present) are usually smaller than continental ones. These cases involve ectothermic carnivores on islands too small to support much mammalian competition. However, these lizards are not as large as their extinct Australian relative Megalania, and it has been proposed based on fossil evidence that the ancestors of these varanids first evolved their large size in Australia and then dispersed to Indonesia.[35] If this is true, rather than being insular giants they would be viewed as examples of phyletic gigantism. Supporting this interpretation is evidence for a lizard in Pliocene India, Varanus sivalensis, comparable in size to V. komodoensis.[35] Nevertheless, given that Australia is often described as the world's largest island and that the related Megalania, the largest terrestrial lizard known in the fossil record, was restricted to Australia, the perception of the largest Australasian/Indonesian lizards as insular giants may still have some validity.

- Giant tortoises in the Galápagos Islands and the Seychelles, the largest extant tortoises, as well as extinct tortoises of the Mascarenes and Canary Islands, are often considered examples of island gigantism. However, during the Pleistocene, comparably sized or larger tortoises were present in Australia (Meiolania), southern Asia (Megalochelys), Europe[36] (Titanochelon), Madagascar (Aldabrachelys), North America[37] (Hesperotestudo) and South America[38] (Chelonoidis, the same genus now found in the Galápagos[39]), and on a number of other, more accessible islands of Oceania and the Caribbean.[37] In the late Pliocene they were also present in Africa ("Geochelone" laetoliensis[40]). The present situation of large tortoises being found only on remote islands appears to reflect that these islands were discovered by humans recently and have not been heavily populated, making their tortoises less subject to overexploitation.

- Hatzegopteryx has features of island gigantism such as a more robust bodyplan and occupying niches taken by megafauna elsewhere (in this case, theropod dinosaurs).[41] However, similar sized giant pterosaurs occurred elsewhere, though nowhere near as robust.

Amphibians

Arthropods

Gastropods

Flora

In addition to size increase, island plants may also exhibit "insular woodiness".[49] The most notable examples are the megaherbs of New Zealand's subantarctic islands.[citation needed] Increased leaf and seed size was also reported in some island species regardless of growth form (herbaceous, bush, or tree).[50]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Based on the estimated total length of H. delcourti, ~23.6 in,[28] and the average length of a member of Diplodactylus, the most species-rich genus of Australian diplodactylid geckos, ~3.5 in.[29]

- Based on the average total length of the larger subspecies, R. l. leachianus, ~15.5 in,[30] and the average length of a member of Diplodactylus, the most species-rich genus of Australian diplodactylid geckos, ~3.5 in.[29]

- Based on the average mass of the larger subspecies, R. l. leachianus, ~240 g,[30] with the average weight of a member of Diplodactylus, the most species-rich genus of Australian diplodactylid geckos, ~4 g.[29]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads