Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Irish Catholic Martyrs

Irish Catholic men and women martyed by English monarch From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Irish Catholic Martyrs (Irish: Mairtírigh Chaitliceacha na hÉireann) were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for both a life of heroic virtue and for dying for their Catholic faith between the reign of King Henry VIII and Catholic Emancipation in 1829.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The more than three century-long religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland came in waves, caused by an overreaction by the State to certain incidents and interspersed with intervals of comparative respite.[1][need quotation to verify]

The 1975 canonization of Archbishop Oliver Plunkett, who was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on 1 July 1681, as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales raised considerable public interest in other Irishmen and Irishwomen who had similarly died for their Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries.[citation needed] On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II beatified an additional 17 martyrs and assigned June 20, the anniversary of the 1584 martyrdom of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley, as their feast day.[2]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Henry VIII

Religious persecution of Catholics in Ireland began under King Henry VIII (then Lord of Ireland) after his excommunication in 1533.[3] The Irish Parliament adopted the Acts of Supremacy, which declared the Irish Church subservient to the State.[4] In response, Irish bishops, priests, and laity who continued to pray for the pope during Mass were tortured and killed.[5] The Treasons Act 1534 defined even unspoken mental allegiance to the Holy See as high treason. Many were imprisoned on this basis. Alleged traitors who were brought to trial.[6] King Henry and Thomas Cromwell continued Cardinal Wolsey's policies of centralizing government power in Dublin Castle and sought to destroy the political and military independence of both the Old English nobility, the Irish clans, and the Gaelic nobility of Ireland.[citation needed] This, in addition to the King's religious policy, ultimately triggered Old English aristocrat Silken Thomas, 10th and last Earl of Kildare, to launch a 1534-1535 military uprising against the rule of the House of Tudor in Ireland.[7]

On c.30 July 1535 John Travers, a graduate of Oxford University and the Chancellor of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, was executed in Dublin for writing a volume denouncing the Act of Supremacy.[8] He was burned at the stake in the Common then known as, "Oxmantown Green", part of which has since become Smithfield Market on the city's Northside.[9][7][10]

Elizabeth I

The focus of religious persecution turned from Catholics to Protestants after the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary, but after Mary's death in November 1558, her sister Queen Elizabeth I arranged for Parliament to pass the Act of Supremacy of 1559, which re-established the control by the State over the Church within her dominions and criminalized religious dissent as high treason.[citation needed] While reviving Thomas Cranmer's prayerbook, the Queen ordered the Elizabethan religious settlement to favor High Church Anglicanism, which preserved many traditionally Catholic ceremonies. Meanwhile, the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity (1559), the Prayer Book of 1559, and the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) mixed the doctrines of Protestantism and Caesaropapism.[11] From the early years of her reign, pressure was put on all her subjects to conform to the "Established Church" of the realm or be considered guilty of high treason. Prosecutions for Recusancy and refusals to take the Oath of Supremacy, the issuing of torture warrants, and the use of priest hunters escalated rapidly.[citation needed]

In 1563 the Earl of Essex issued a proclamation, by which all Catholic priests, secular and regular, were forbidden to officiate, or even to reside in Dublin or in The Pale. Fines and penalties were strictly enforced for Recusancy from the Anglican Sunday service; before long. Catholic priests and others were hunted into the Mass rocks in mountains and caves; and the parish churches and few monastic chapels which had escaped earlier destruction were also destroyed.[12] It ultimately resulted in Pope Pius V's 1570 papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which, "released [Elizabeth I's] subjects from their allegiance to her".[1]

In Ireland the First Desmond Rebellion, led by James FitzMaurice FitzGerald and which sought to replace Queen Elizabeth I with Don John of Austria as High King of Ireland, was launched in 1569, at almost the same time as the Northern Rebellion in England. The Wexford Martyrs were found guilty of high treason for aiding in the escape of James Eustace, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass and refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and declare Elizabeth I of England to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland.[citation needed]

The ongoing religious persecution also became highly significant as the primary cause of the Nine Years War, which similarly sought to replace Queen Elizabeth with a High King from the House of Habsburg.[citation needed] The war formally began when Red Hugh O'Donnell expelled English High Sheriff of Donegal Humphrey Willis, but not before Red Hugh listed his reasons for taking up arms against the House of Tudor and alluded in particular to the recent torture and executions of Archbishop Dermot O'Hurley and Bishop Patrick O'Hely.[13]

Beatified Martyrs of this period include Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, who died as a prisoner of conscience in Dublin Castle for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, 1584[14] Dominic Collins, was Jesuit lay brother and former Catholic League military officer, under the nom de guerre "Captain de la Branche", who served during the Brittany Campaign of the French Wars of Religion. Captured following Battle of Kinsale and the 11-day Siege of Dunboy. Officially hanged for high treason, but in reality for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, outside the walls of his native Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[15]

King James I

According to D.P. Conyngham, "It was fondly hoped by the Catholics of Ireland that the accession of James would bring peace and repose to the Church in that distracted and oppressed country. A general feeling of relief and joy pervaded all classes. Many of those who had been forced into exile returned to their native country: churches were rebuilt - monasteries repaired - the sacred duties of the sanctuary were resumed, and the offices of the Church were performed with undisturbed safety throughout the Kingdom. This state of comparative tranquility was not, however, suffered to continue..."[16] A Royal edict issued on 4 July 1605 announced that Elizabethan-era Recusancy laws were to be rigorously enforced and added, "It hath seemed proper to us to proclaim, and we hereby make it known to our subjects in Ireland, that no toleration shall ever be granted by us. This we do for the purpose of cutting off all hope that any other religion shall be allowed - save that which is consonant to the laws and statutes of this realm."[17]

King Charles I

According to historian D.P. Conyngham, "Ireland was torn by contending factions, and was oppressed by two belligerents during the reign of Charles. The Catholics took up arms in defense of themselves, their religion, and their King. Charles, with the proverbial fickleness of the Stuarts, when pressed by the Puritans, persecuted the Irish, while he encouraged them when he hoped their loyalty and devotion would be the means of establishing his royal prerogative. For eight years Ireland was the theatre of the most desolating war and implacable persecution."[18] Beatified Martyrs of the era included Peter O'Higgins, Dominican Order, hanged outside the walls of Dublin at St Stephen's Green, on 24 March 1642[19][20][21]

The Commonwealth and Protectorate of England

On 24 October 1644, the Puritan-controlled Rump Parliament in London, seeking to retaliate for acts of sectarian violence like the Portadown massacre during the recent 1641 uprising, resolved, "that no quarter shall be given to any Irishman, or to any papist born in Ireland." Upon landing with the New Model Army at Dublin, Oliver Cromwell issued orders that no mercy was to be shown to the Irish, whom he said were to be treated like the Canaanites during the time of the Old Testament prophet Joshua.[22] After taking Ireland in 1653, the New Model Army turned Inishbofin, County Galway, into a prison camps for Catholic priests arrested while exercising their religious ministry covertly in other parts of Ireland. Inishmore, in the Aran Islands, was used for exactly the same purpose. The last priests held on both islands were finally released following the Stuart Restoration in 1662.[23] Officially beatified martyrs of the era include Theobald Stapleton, (Irish: Teabóid Gálldubh), slain during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647.[24] Another beatified martyr was John Kearney (1619-1653) who was born in Cashel, County Tipperary and joined the Franciscans at the Kilkenny friary. After his novitiate, he went to Leuven in Belgium and was ordained in Brussels in 1642. Returned to Ireland, he taught in Cashel and Waterford, and was much admired for his preaching. In 1650 he became erenagh of Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, he was arrested by the New Model Army while continuing to exercise an illegal and underground priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir and executed by hanging at Clonmel, County Tipperary on 21 March 1653. He lies buried in the chapter hall of the suppressed friary of Cashel.[25][26]

Age of the Whig oligarchy

A 1709 Penal Act demanded that Catholic priests take the Oath of Abjuration, and recognise the Protestant Queen Anne as Supreme Head of the Church within all her dominions and declare that Catholic doctrine regarding Transubstantiation to be "base and idolatrous".[27] Priests who refused to take the oath abjuring the Catholic faith were arrested and executed.[citation needed] Priests had to register with the local magistrates to be allowed to preach, and most did so.[citation needed] Bishops were not permitted to register.[28] In 1713, the Irish House of Commons declared that "prosecution and informing against Papists was an honourable service", which revived the Elizabethan era profession of the priest hunter,[29] the most infamous of whom remains John O'Mullowny, nicknamed (Irish: Seán na Sagart), of the Partry Mountains in County Mayo.[30] The reward rates for capture varied from £50–100 for a bishop, to £10–20 for the capture of an unregistered priest: substantial amounts of money at the time.[28]

Remove ads

Investigations

Summarize

Perspective

The Irish Martyrs suffered over several reigns and even at the hands of both sides during regime change wars.[citation needed] There was a long delay by the Holy See in opening an Apostolic Process into the Sainthood Causes of the Irish Catholic Martyrs for fear of escalating the ongoing religious persecution. Further complicating the investigation is that the records of these martyrs could not be safely investigated or publicized except by the Irish diaspora in Catholic Europe, due to the danger of being caught possessing such evidence at home. Details of their endurance in most cases have been lost.[4] The first general catalog, that of Father John Houling, S.J., was compiled in Portugal between 1588 and 1599. It is styled a very brief abstract of certain persons whom it commemorates as sufferers for the Faith under Elizabeth.[5]

Detailed accounts were also written and published by Philip O'Sullivan Beare, David Rothe, Luke Wadding, Richard Stanihurst, Anthony Bruodin, John Lynch, John Coppinger, and John Mullin.[31] A series of re-publications of primary sources relating to the period of the persecutions and meticulous comparisons against archival Government documents in London and Dublin were also made by Daniel F. Moran and other historians. The first Apostolic Process under Canon Law began in Dublin in 1904, after which a positio was submitted to the Holy See.[citation needed]

In the 12 February 1915 Apostolic decree In Hibernia, heroum nutrice, Pope Benedict XV formally authorized the formal introduction of additional Causes for Catholic sainthood.[32] During a further Apostolic Process held at Dublin between 1917 and 1930 and against the backdrop of the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, the evidence surrounding 260 alleged cases of Catholic martyrdom were further investigated, after which the findings were again submitted to the Holy See.[31] So far, the only Martyr to complete the process was Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, who was Canonized as a Saint in 1975 by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.[4] Plunkett was certainly targeted during the anti-Catholic witch hunt connected to Titus Oates and was executed following a show trial motivated solely in odium fidei ("out of hatred of the Faith"), instead of being in any way guilty of than any real crime against the state.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Lists of Martyrs

Summarize

Perspective

Canonized Martyrs

12 October 1975 by Pope Paul VI.

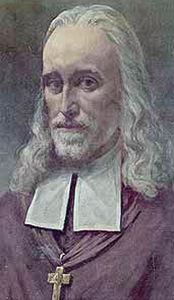

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, 1 July 1681 at Tyburn, London; beatified 1920[citation needed]

Beatified Martyrs

15 December 1929 by Pope Pius XI.[citation needed]

- John Carey (alias Terence Carey) and Patrick Salmon, laymen, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Cornelius (Irish: Seán Conchobhar Ó Mathghamhna), Jesuit priest, 4 July 1594 at Dorchester, England

- John Roche, layman, 30 August 1588 at Tyburn, England

22 November 1987 by Pope John Paul II.[citation needed]

- Charles Mahoney (alias Meehan), Franciscan, 21 August 1679, Ruthin, Wales

The 17 Blessed Irish Martyrs

27 September 1992 by Pope John Paul II.[citation needed]

- Patrick O'Hely (Irish: Pádraig Ó hÉilí), Franciscan Bishop of Mayo, betrayed to Lord President of Munster Sir William Drury by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock 13 August 1579

- Conn O'Rourke (Irish: Conn Ó Ruairc), Franciscan Friar, betrayed to the priest hunters by the Rebel Earl and Countess of Desmond and executed at Kilmallock, 13 August 1579

- Wexford Martyrs, 5 July 1581: Matthew Lambert, Robert Myler, Edward Cheevers, Patrick Cavanagh (Irish: Pádraigh Caomhánach), John O'Lahy, and one other unknown individual

- Margaret Ball, former Lady Mayoress of Dublin, died 1584, as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle[14]

- Dermot O'Hurley (Irish: Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile), Archbishop of Cashel, sentenced to death by military tribunal and hanged at Lower Baggot Street, then outside the walls of Dublin, 20 June 1584

- Muiris Mac Ionrachtaigh (Maurice MacKenraghty), military chaplain to the Rebel Earl of Desmond, executed at Clonmel, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, 30 April 1585

- Dominic Collins, Jesuit lay brother captured by the Tudor Army following the Siege of Dunboy and executed without trial at Youghal, County Cork, 31 October 1602[15]

- Concobhar Ó Duibheannaigh (Conor O'Devany), Franciscan Bishop of Down & Connor, 11 February 1612

- Patrick O'Loughran, priest from County Tyrone and former spiritual director to Aodh Mór Ó Néill, 11 February 1612

- Francis Taylor, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, died as a prisoner of conscience inside Dublin Castle, 1621

- Peter O'Higgins OP, Prior of the Dominican monastery of Naas, hanged under orders from Sir Charles Coote, despite O'Higgins' well-documented and successful efforts to protect Protestant civilians from sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing during the Irish rebellion of 1641, at St Stephen's Green, then outside the walls of Dublin, on 24 March 1642[19][20][21]

- Theobald Stapleton, (Irish: Teabóid Gálldubh), Catholic priest and one of the creators of modern Irish language orthography. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Fr. Stapleton sought sanctuary inside St. Patrick's Cathedral upon the Rock of Cashel and was slain, alongside six other priests, by the Parliamentary Army of Lord Inchiquin (Irish: Murchadh na dTóiteán) during the Sack of Cashel, 15 September 1647. Fr. Stapleton is said to have blessed his attackers with holy water moments before his death.[24]

- Terence O'Brien OP, Dominican Order, Bishop of Emly, captured following the Siege of Limerick, court martialed, sentenced to death, and hanged by New Model Army General Henry Ireton.[33] Gallows Green, Limerick City, 31 October 1651

- John Kearney, Franciscan Prior of Cashel, hanged at Clonmel, officially for high treason, but in reality for covertly continuing his priestly ministry throughout the valley of the River Suir in nonviolent resistance to the Commonwealth of England's recent decree banishing of all Catholic priests, 21 March 1653[25][26]

- William Tirry (Irish: Liam Tuiridh), Augustinian Friar from St. Austin's Abbey in Cork City, captured by the priest hunters at Fethard, County Tipperary and executed by hanging, officially for high treason against The Protectorate and Commonwealth of England, but in reality for remaining in Ireland and continuing his priestly ministry in nonviolent resistance of the regime's decree of banishment for all priests, at Clonmel, County Tipperary, 12 May 1654

Remove ads

Church dedications

Various parish churches have also been dedicated since 1992 to the Irish Catholic Martyrs, including:

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballyraine, Letterkenny,[14] County Donegal

- Church of the Irish Martyrs, Ballycane, Naas[34] County Kildare

See also

- List of Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation

- Charles Reynolds (Irish: Cathal Mac Raghnaill) (c. 1496 – 1535), envoy of Silken Thomas to the Holy See who secured a Papal promise to excommunicate Henry VIII over the Act of Supremacy.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads