Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Itinerant court

Government that travels from place to place From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

An itinerant court was a migratory form of government in European kingdoms during the Early Middle Ages. It was an alternative to having a capital city, a permanent political center governed by a kingdom.

Medieval Western Europe was generally characterized by a political rule wherein the highest political authorities frequently changed their location, bringing parts of the country's central government on their journey. Therefore, such a realm had no actual center or permanent seat of government. Itinerant courts were gradually replaced from the thirteenth century, when stationary royal residences began to develop into modern capital cities.

Remove ads

Holy Roman Empire

Summarize

Perspective

The itinerant court system of ruling a country is strongly associated with German history, where the emergence of a capital city took a long time. The German itinerant regime (Reisekönigtum) was the usual form of royal or imperial government from the Frankish period and up to late medieval times.[1] The Holy Roman Emperors did not rule from any permanent central residence during or after the Middle Ages. They constantly traveled, with their family and court, through the empire. A key reason was certainly that—unlike in England and France—there was no hereditary monarchy in the Holy Roman Empire, but rather the electoral principle, which led to kings of very different regional origins being elected in imperial elections.

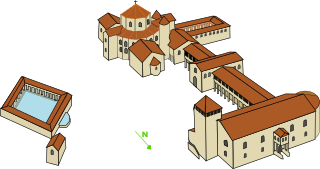

The Holy Roman Empire did not have a capital city. The emperors owned their varying dynastic lands, including castles, but could not limit themselves to these if they wanted to keep control of their large empire, including its often-rebellious regional princes. Therefore, the emperor and other princes ruled by constantly changing their residences. The Merovingian kings of the Frankish Empire practiced this system, and the subsequent Carolingian dynasty adopted both the custom and its associated palaces (Kaiserpfalz, lit. 'royal palace'). During the reigns of successive emperors, these palaces were expanded, abandoned, rebuilt elsewhere (often on the kings' own estates), and often became part of the royal estates of the kings' successors. Royal pfalzes were scattered around the whole country—notably in accessible, fertile areas—and surrounded by imperial property administrated by the palace to ensure supplies.

The locations of royal estates or palaces depended on several factors. Royal granges served as transit quarters and were therefore set up at a distance of 15–19 miles (24–31 km),[2] which corresponded to a day's journey by the royal entourage with horses and carriages. Individual riders, such as postal riders, covered much greater distances, up to 75 miles per day on dry ground. In 1146, Conrad III of Germany could travel as fast as 41 miles a day on his journey from Frankfurt to Weinheim.[3] During a year, large distances were covered. However, these distances could not be maintained on all routes—there were large territories in which no royal pfalz or grange existed, or lacked nearby monasteries or towns. In these cases, the emperors and kings spent the night in tent camps.[4] This also occurred during campaigns and sieges in which the kings took part.

Pfalzes were often located near Roman urban remnants, which constituted the oldest cities in Germany and France. These settlements were also mostly located on navigable rivers—mainly the Rhine, Main, and Danube—which enabled quick and comfortable travel and facilitated supplying. Old bishoprics were often located in these places, another advantage in that bishops were usually more loyal to the king than regional dukes, who pursued their own dynastic goals.

The routes the court followed during the journeys were called itinerarium. The composition of the ruler's retinue constantly changed, depending on what area the court was passing through and which noblemen joined or left.

Remove ads

In other countries

Summarize

Perspective

The itinerant court was the case in most other contemporary European countries, where terms like "corte itinerante" describe this phenomenon. Kings and their companions traveled continuously from one royal palace to the next. Early historical sources describe Scotland as being ruled by an itinerant court, with the Parliament of Scotland assembling in many different places. In Saxon England, conditions were the same.[5]

A more centralized way of ruling did evolve during this time, but only slowly and gradually.[6] London and Paris began to develop into permanent political centers from the late 1300s, and Lisbon showed similar tendencies. Smaller kingdoms too had a similar, but slower development. Spain, on the other hand, lacked a fixed royal residence until the late 1500s, when Philip II elevated El Escorial outside Madrid to this rank.[7]

Emperor Charles V made 40 journeys during his lifetime, traveling from country to country with no single fixed capital city. It is estimated that he spent a quarter of his reign on the road.[8] He made ten trips to the Low Countries, nine to German-speaking lands, seven to Spain, seven to Italian states, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa. As he said in his last public speech, "My life has been one long journey."[9] During his travels, Charles V left a documentary trail nearly everywhere he went, allowing historians to surmise that he spent nearly half his life (over 10,000 days) in the Low Countries and almost one-third (6,500 days) in Spain. He spent more than 3,000 days in what is now Germany and nearly 1,000 days in Italy, with much of the remainder in France (195), North Africa (99), and England (44). For 260 days, his exact location is unrecorded, all of them being days spent at sea traveling between his dominions.[10]

Remove ads

The evolving capital city

Summarize

Perspective

Holy Roman Empire

Germany did not develop a fixed capital city during the medieval or early modern period—its alternative solution was a decentralized state (Multizentralität, "pluricentricity") until the late modern period.

England

England's central political power was permanently established in London, approximately in the middle of the fourteenth century. London's position as a financial center had been firmly established several centuries earlier.[when?] King Henry II of England (1133–1189) was attracted by the city's great wealth, but he was hesitant about taking up residence there. During his reign, London became as near to an economic capital as the conditions of the age allowed. But its very prosperity and its extensive and long-recognized liberties, the latter subsequently characterized in Magna Carta as 'ancient', forbade it as a desirable place of residence for the king and his court, preventing it from becoming a political capital.

The king often wished to be near London, but he claimed the same power to control the court that the citizens demanded to govern their city. The only way to avoid conflict between the household and municipal jurisdictions was for the king to keep away from the latter much of the time. He could only be in the city as a guest or a conqueror. Accordingly, he seldom ventured within the city walls; on such occasions, he established himself either in the Tower Fortress or at his Palace of Westminster just outside the City of London.

London was the natural leader among English towns. To control England, the kings needed to maintain London first. London was too powerful to handle; it took centuries before the monarchs settled there. They tried, unsuccessfully, to drive the London merchants out of business by making Westminster a rival economic center. They tried to find some other suitable place in the kingdom to deposit their archives, which were gradually growing too large and heavy to be transported on their unending journeys.[11]

York tended towards becoming a political capital during times of war with Scotland. The Hundred Years' War against France caused the political center of gravity to shift to the southern parts of England, where London was dominant. Gradually, many state institutions ceased to follow the king on his journeys and established themselves permanently in London: the Treasury, Parliament, and the court. The king himself was last to take up permanent residence in London. It was only possible for him to make London his capital city after he had become powerful enough to "tame the financial metropolis" and transform it into an obedient tool of the State's authority.[11]

Remove ads

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads