Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Jain literature

Texts related to the religion of Jainism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Jain literature (Sanskrit: जैन साहित्य) refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit (Middle-Indo Aryan) language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Jain literature is primarily divided between the canons of the Digambara and Śvētāmbara orders. These two main sects of Jainism do not always agree on which texts should be considered authoritative.

More recent Jain literature has also been written in other languages, like Marathi, Tamil, Rajasthani, Dhundari, Marwari, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam and more recently in English.

Remove ads

Origins: The Oral Tradition (Śrutajñāna)

Summarize

Perspective

According to Jain tradition, the teachings that form the basis of their scriptures are eternal.[1] It's believed that in each universal time cycle, twenty-four tīrthaṅkaras reveal these truths.[1] The first tīrthaṅkara of the current cycle, Ṛṣabhanātha, is considered the original source of the teachings in this era, millions of years ago.[1]

Jains believe the tīrthaṅkaras deliver their teachings in a divine preaching hall called the samavasaraṇa, which are heard simultaneously by gods, ascetics, and laypersons.[2] This divine discourse itself is known as śrutajñāna ("heard knowledge").[2] Crucially, this initial form is not a written text but an oral transmission.[3][4]

The tradition holds that the chief disciples (Gaṇadharas) of a tīrthaṅkara possess the unique ability to perfectly understand and recall this divine discourse.[3] They are credited with converting the śrutajñāna into structured scriptures (suttas), initially comprising the fourteen Pūrvas (ancient or prior texts) and the eleven Aṅgas ("limbs").[5] The complete structure is often referred to as the "twelve-limbed basket" (duvala samgagani pidaga), as the twelfth Aṅga contained the Pūrvas.[5][1][6]

For many centuries, these foundational scriptures were meticulously transmitted orally from teacher (guru) to disciple (shishya) through rigorous memorization and chanting.[citation needed] This emphasis on oral transmission was a defining characteristic of the early literary tradition.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Datings

While some authors date the composition of the Jain Agamas starting from the 6th century BCE,[7] some western scholars, such as Ian Whicher and David Carpenter, argue that the earliest portions of Jain canonical works were composed around the 4th or 3rd century BCE.[8][9] According to Johannes Bronkhorst it is extremely difficult to determine the age of the Jain Agamas, however:

Mainly on linguistic grounds, it has been argued that the Ācārāṅga Sūtra, the Sūtrakṛtāṅga Sūtra, and the Uttarādhyayana Sūtra are among the oldest texts in the canon.[10]

Elsewhere, Bronkhorst states that the Sūtrakṛtāṅga "dates from the 2nd century BCE at the very earliest," based on how it references the Buddhist theory of momentariness, which is a later scholastic development.[10]

Remove ads

The Great Schism and the Divergence of Canons

Summarize

Perspective

The Jaina congregation gradually split into the two sects. While Śvetāmbaras maintain that the schism happened in the 1st century CE, Digambaras hold that it happened in 2nd century BCE. Śvetāmbaras hold that the theory of Jain monks migrating from North to South is a fabricated account.[11] Some scholars specifically state that the said lore was developed after 600 CE and is inauthentic.[12]

Śvetāmara Efforts to Preserve the Canon

Śvetāmbaras convened the First Council at Pataliputra (modern Patna) around 300 BCE (traditional dating varies).[14] During this council, the monks pooled their collective memory to compile the eleven Aṅgas.[14] However, the twelfth Aṅga, the Dṛṣṭivāda, which contained the fourteen Pūrvas, was found to be incomplete or lost, as Bhadrabāhu, the only master who knew it fully, was absent.[15] While Sthulabhadra learned 10 of the 14 purvas from Bhadrabāhu when the latter was in Nepal, the full transmission was broken.[16][page needed][17][page needed]

Further efforts to consolidate the texts occurred, possibly including a council in the Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves under King Kharavela in the 2nd century BCE.[18]

The most definitive step for the Śvetāmbara tradition was the Council of Vallabhi (in Gujarat) held around 454 or 466 CE, presided over by Devardhigaṇi Kṣamāśramaṇa.[18][19][20] Faced with the ongoing weakening of memory, the council made the historic decision to commit the entire remembered canon to writing in manuscript form.[18][19][20]

The Śvetāmbara sect considers this written canon, based on the Vallabhi council texts, to be the authentic Agamas, derived from the original oral tradition passed down from Mahavira, even while acknowledging that the twelfth Aṅga and parts of the Pūrvas are missing.[5][21]

Digambara View: The Canon Was Lost

The Digambara tradition holds a fundamentally different view.[22][23] They believe that due to the famine and the passage of time, the original Aṅgas and Pūrvas were completely lost by around the 2nd century CE.[22][23] They state that Āchārya Bhutabali (1st century CE) was the last ascetic with even partial knowledge of the original canon.[22] They maintain that Āchārya Pushpadanta and Bhutabali wrote the Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama (Six Part Scripture) under guidance of Dharasena, which is held to be one of the oldest Digambara texts (2nd to 3rd century CE).[22][24] Around the same time, Āchārya Gunadhar wrote Kasayapahuda (Treatise on the Passions).[22][25][24]

Consequently, Digambaras reject the scriptures compiled by the Śvetāmbaras at Pataliputra and Vallabhi, viewing them as incomplete and corrupted.[22] This disagreement over the authenticity and survival of the Agamas is a central reason for the historical schism between the two major sects.[26] Lacking the original Agamas, the Digambara tradition instead came to hold authoritative a set of later texts, believed to encapsulate the essence of the lost teachings.[27][28][29]

Remove ads

Svetambara Canon (The Agamas)

Summarize

Perspective

The canons (Siddhāntha) of the Śvētāmbaras are generally composed of the following texts:[19][30]

- Twelve Angās (limbs)

- Āyāraṃga (Jain Prakrit; Sanskrit: Ācāranga, meaning: 'On monastic conduct')

- Sūyagaḍa (Sūtrakṛtāṅga, 'On heretical systems and views')

- Ṭhāṇaṃga (Sthānāṅga, 'On different points [of the teaching]')

- Samavāyaṃga (Samavāyāṅga, 'On "rising numerical groups"')

- Viyāha-pannatti / Bhagavaī (Vyākhyā-prajñapti or Bhagavatī, 'Exposition of explanations' or 'the holy one')

- Nāyā-dhamma-kahāo (Jñāta-dharmakathānga, 'Parables and religious stories')

- Uvāsaga-dasāo (Upāsaka-daśāḥ,'Ten chapters on the Jain lay follower')

- Aṇuttarovavāiya-dasāo (Antakṛd-daśāḥ, 'Ten chapters on those who put an end to rebirth in this very life')

- Anuttaraupapātikadaśāh (Anuttaropapātika-daśāḥ, 'Ten chapters on those who were reborn in the uppermost heavens')

- Paṇha-vāgaraṇa (Praśna-vyākaraṇa, 'Questions and explanations')

- Vivāga-suya (Vipākaśruta,'Bad or good results of deeds performed')

- Diṭhīvāya (Dṛṣṭivāda) - this text was lost after 1000 years of Mahavira.[31]

- Twelve Upāṅgas (auxiliary limbs)

- Uvavāiya-sutta (Sanskrit: Aupapātika-sūtra,'Places of rebirth')

- Rāya-paseṇaijja or Rāyapaseṇiya (Rāja-praśnīya, 'Questions of the king')

- Jīvājīvābhigama (Jīvājīvābhigama, 'Classification of animate and inanimate entities')

- Pannavaṇā (Prajñāpanā, 'Enunciation on topics of philosophy and ethics')

- Sūriya-pannatti (Sūrya-prajñapti, 'Exposition on the sun')

- Jambūdvīpa-pannatti (Jambūdvīpa-prajñapti, 'Exposition on the Jambū continent and the Jain universe')

- Canda-pannatti (Candra-prajñapti, 'Exposition on the moon and the Jain universe')

- Nirayāvaliyāo or Kappiya (Narakāvalikā, 'Series of stories on characters reborn in hells')

- Kappāvaḍaṃsiāo (Kalpāvataṃsikāḥ, 'Series of stories on characters reborn in the kalpa heavens')

- Pupphiāo (Puṣpikāḥ, 'Flowers' refers to one of the stories')

- Puppha-cūliāo (Puṣpa-cūlikāḥ, 'The nun Puṣpacūlā')

- Vaṇhi-dasāo (Vṛṣṇi-daśāh, 'Stories on characters from the legendary dynasty known as Andhaka-Vṛṣṇi')

- Six Chedasūtras (Texts relating to the conduct and behaviour of monks and nuns)

- Āyāra-dasāo (Sanskrit: Ācāradaśāh, 'Ten [chapters] about monastic conduct', chapter 8 is the famed Kalpa-sūtra.)

- Bihā Kappa (Bṛhat Kalpa, '[Great] Religious code')

- Vavahāra (Vyavahāra, 'Procedure')

- Nisīha (Niśītha, 'Interdictions')

- Jīya-kappa (Jīta-kalpa, Customary rules), only accepted as canonical by Mūrti-pūjaks

- Mahā-nisīha (Mahā-niśītha, Large Niśītha), only accepted as canonical by Mūrti-pūjaks

- Four Mūlasūtras ('Fundamental texts' which are foundational works studied by new monastics)

- Dasaveyāliya-sutta (Sanskrit: Daśavaikālika-sūtra), this is memorized by all new Jain mendicants

- Uttarajjhayaṇa-sutta (Uttarādhyayana-sūtra)

- Āvassaya-sutta (Āvaśyaka-sūtra)

- Piṇḍa-nijjutti and Ogha-nijjutti (Piṇḍa-niryukti and Ogha-niryukti), only accepted as canonical by Mūrti-pūjaks

- Two Cūlikasūtras ("appendixes")

- Nandī-sūtra – discusses the five types of knowledge

- Anuyogadvāra-sūtra – a technical treatise on analytical methods, discusses Anekantavada

Miscellaneous collections

To reach the number 45, Mūrtipūjak Śvētāmbara canons contain a "Miscellaneous" collection of supplementary texts, called the Paiṇṇaya suttas (Sanskrit: Prakīrnaka sūtras, "Miscellaneous"). This section varies in number depending on the individual sub-sect (from 10 texts to over 20). They also often included extra works (often of disputed authorship) named "supernumerary Prakīrṇakas".[32] The Paiṇṇaya texts are generally not considered to have the same kind of authority as the other works in the canon. Most of these works are in Jaina Māhārāṣṭrī Prakrit, unlike the other Śvetāmbara scriptures which tend to be in Ardhamāgadhī. They are therefore most likely later works than the Aṅgas and Upāṅgas.[32]

Mūrtipūjak Jain canons will generally accept 10 Paiṇṇayas as canonical, but there is widespread disagreement on which 10 scriptures are given canonical status. The most widely accepted list of ten scriptures are the following:[32]

- Cau-saraṇa (Sanskrit: Catuḥśaraṇa, The 'four refuges')

- Āura-paccakkhāṇa (Ātura-pratyākhyāna, 'Sick man's renunciation')

- Bhatta-parinnā (Bhakta-parijñā, 'Renunciation of food')

- Saṃthāraga (Saṃstāraka, 'Straw bed')

- Tandula-veyāliya (Taṇḍula-vaicārika, 'Reflection on rice grains')

- Canda-vejjhaya (Candravedhyaka, 'Hitting the mark')

- Devinda-tthaya (Devendra-stava, 'Praise of the kings of gods')

- Gaṇi-vijjā (Gaṇi-vidyā, 'A Gaṇi's knowledge')

- Mahā-paccakkhāṇa (Mahā-pratyākhyāna, 'Great renunciation')

- Vīra-tthava (Vīra-stava, 'Great renunciation')

From the 15th century onwards, various Śvetāmbara subsects began to disagree on the composition of the canon. Mūrtipūjaks ("idol-worshippers") accept 45 texts, while the Sthānakavāsins and Terāpanthins only accept 32.[33]

Remove ads

Digambara Canon (The Siddhanta)

Summarize

Perspective

The Digambara canon of scriptures includes these two main texts, three commentaries on the main texts, and four (later) Anuyogas (expositions), consisting of more than 20 texts.[34][35]

The great commentator Virasena wrote two commentary texts on the Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama, the Dhaval‑tika on the first five volumes and Maha‑dhaval‑tika on the sixth volume of the Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama, around 780 CE.[24] Virasena and his disciple, Jinasena, also wrote a commentary on the Kaşāyapāhuda, known as Jaya‑dhavala‑tika.[25][24]

There is no agreement on the canonical Anuyogas ("Expositions"). The Anuyogas were written between the 2nd and the 11th centuries CE, either in Jaina Śaurasenī Prakrit or in Sanskrit.[36]

The expositions (Anuyogas) are divided into four literary categories:[34]

- The 'first' (Prathamānuyoga) category contains various works such as Jain versions of the Rāmāyaṇa (like the 7th-century Padma-purāṇa by Raviṣeṇa) and Mahābhārata (like Jinasena's 8th century Harivaṃśa-purāṇa), as well as 'Jain universal histories' (like Jinasena's 8th-century Ādi-purāṇa).

- The 'calculation' (Karaṇānuyoga) expositions are mainly works on Jain cosmology (such as Tiloya-paṇṇatti of Yati Vṛṣabha, dating from the 6th to 7th century) and karma (for example, Nemicandra's Gommaṭa-sāra). The Gommatsāra of Nemichandra (fl. 10th century) is one of the most important Digambara works and provides a detailed summary of Digambara doctrine.[37]

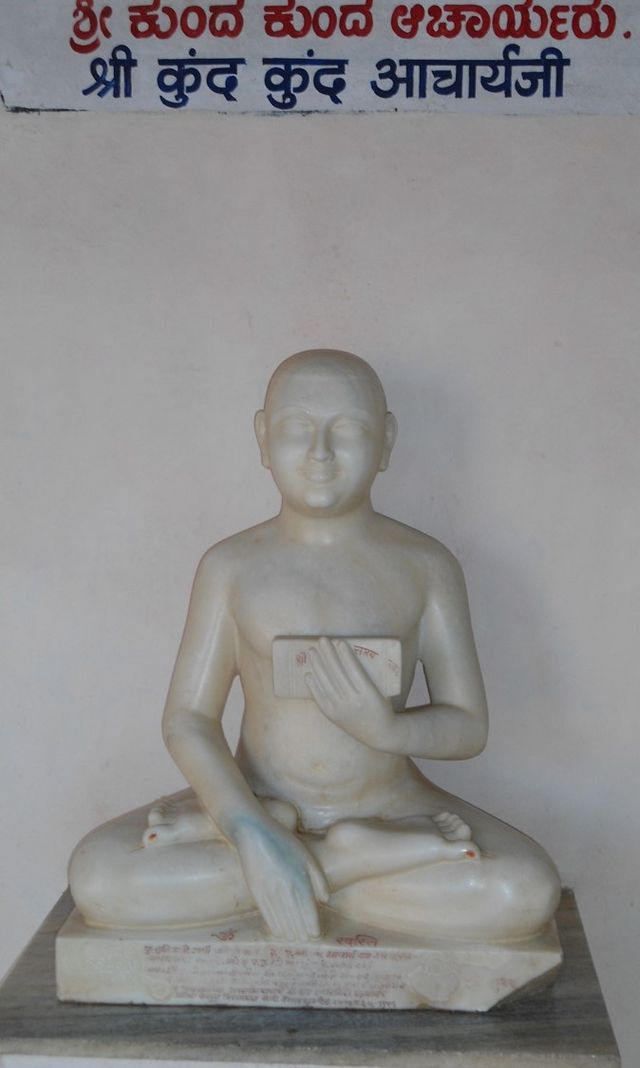

- The 'behaviour' (Caraṇānuyoga) expositions are texts about proper behaviour, such as Vaṭṭakera's Mūlācāra (on monastic conduct, 2nd century) and the Ratnakaraṇḍaka-Śrāvakācāra by Samantabhadra (5th-century) which focuses on the ethics of a layperson.[38] Works in this category also treat the purity of the soul, such as the work of Kundakunda like the Samaya-sāra, the Pancastikayasara, and Niyamasara. These works by Kundakunda (2nd century CE or later) are highly revered and have been historically influential.[39][40][41]

- The 'substance' (Dravyānuyoga) exposition includes texts about ontology of the universe and self. Umāsvāmin's comprehensive Tattvārtha-sūtra is the standard work on ontology and Pūjyapāda's (464–524 CE) Sarvārthasiddhi is one of the most influential Digambara commentaries on the Tattvārtha. This collection also includes various works on epistemology and reasoning, such as Samantabhadra's Āpta-mīmāṃsā and the works of Akalaṅka (720–780 CE), such as his commentary on the Apta-mīmāṃsā and his Nyāya-viniścaya.

Remove ads

Post-Canonical literature

Summarize

Perspective

Philosophy and Logic

There are various later Jain works that are considered post-canonical, that is to say, they were written after the closure of the Jain canons, though the different canons were closed at different historical eras, and so this category is ambiguous.

Thus, Umasvāti's (c. between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE) Tattvarthasūtra ("On the Nature of Reality") is included in the Digambara canon, but not in the Śvētāmbara canons (though they do consider the work authoritative). Indeed, the Tattvarthasūtra is considered the authoritative Jain philosophy text by all traditions of Jainism.[42][43][44] It has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sūtras and Yogasūtras have in Hinduism.[42][45][46]

Other non-canonical works include various texts attributed to Bhadrabahu (c. 300 BCE) which are called the Niryuktis and Samhitas.

According to Winternitz, after the 8th century or so, Svetambara Jain writers, who had previously worked in Prakrit, began to use Sanskrit. The Digambaras also adopted Sanskrit somewhat earlier.[47] The earliest Jain works in Sanskrit include the writings of Siddhasēna Divākara (c. 650 CE), who wrote the Sanmatitarka ('The Logic of the True Doctrine') is the first major Jain work on logic written in Sanskrit.[48]

Other later works and writers include:

- Jinabhadra (6th–7th century) – author of Avasyaksutra (Jain tenets) Visesanavati and Visesavasyakabhasya (Commentary on Jain essentials).

- Mallavadin (8th century) – author of Nayacakra and Dvadasaranayacakra (Encyclopedia of Philosophy) which discusses the schools of Indian philosophy.[49]

- Haribhadra-sūri (c 8th century) is an important Svetambara scholar who wrote commentaries on the Agamas. He also wrote the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, a key Jain text on Yoga which compares the Yoga systems of Buddhists, Hindus and Jains. Gunaratna (c. 1400 CE) wrote a commentary on Haribhadra's work.

- Prabhacandra (8th–9th century) – Jain philosopher, composed a 106-Sutra Tattvarthasutra and exhaustive commentaries on two key works on Jain Nyaya, Prameyakamalamartanda, based on Manikyanandi's Parikshamukham and Nyayakumudacandra on Akalanka's Laghiyastraya.

- Abhayadeva (1057–1135 CE) – author of Vadamahrnava (Ocean of Discussions) which is a 2,500 verse tika (Commentary) of Sanmartika and a great treatise on logic.[49]

- Hemachandra (c. 1088 – c. 1172 CE) wrote the Yogaśāstra, a textbook on yoga and Adhyatma Upanishad. His minor work Anyayogavyvaccheda gives outlines of the Jaina doctrine in form of hymns. This was later detailed by Mallisena (c. 1292 CE) in his work Syadavadamanjari.

- Vadideva (11th century) – He was a senior contemporary of Hemacandra and is said to have authored Paramananayatattavalokalankara and its voluminous commentary syadvadaratnakara that establishes the supremacy of doctrine of Syādvāda.

- There are also other important commentators on the Agamas, including Abhayadeva-sūri (c. 11th century) and Malayagiri (c. the 12th century).

- Vidyanandi (11th century) – Jain philosopher, composed the brilliant commentary on Acarya Umasvami's Tattvarthasutra, known as Tattvarthashlokavartika.

- Devendrasuri wrote the Karmagrantha which is an exposition of the Jain theory of Karma.

- Yaśovijaya (1624–1688) was a Jain scholar of Navya-Nyāya and wrote Vrttis (commentaries) on most of the earlier Jain Nyāya works by Samantabhadra, Akalanka, Manikyanandi, Vidyānandi, Prabhācandra and others in the then-prevalent Navya-Nyāya style. Yaśovijaya has to his credit a prolific literary output – more than 100 books in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Gujarati and Rajasthani. He is also famous for Jnanasara (essence of knowledge) and Adhayatmasara (essence of spirituality).

- The Lokaprakasa of Vinayavijaya was written in the 17th century CE.

- Srivarddhaeva (aka Tumbuluracarya) wrote a Kannada commentary on Tattvarthadigama-sutra.

- Atmasiddhi Shastra is a spiritual treatise in verse, composed in Gujarati by the nineteenth century Jain saint, philosopher poet Shrimad Rajchandraji (1867–1901) which comprises 142 verses explaining the fundamental philosophical truths about the soul and its liberation. It propounds six fundamental truth on soul which are also known as Satapada (six steps).

- The Saman Suttam is a compilation of ancient texts and doctrines recognised by all Jain sects, assembled primarily by Jinendra Varni and then examined and approved by monks of different sects and other scholars in 1974.

Grammar and Linguistics

Jainendra Vyākaraṇa of Acharya Pujyapada and Śākaṭāyana-vyākaraṇa of Śākaṭāyana (also called Pālyakīrti)[50] are both works on grammar written in c. 9th century CE.[51]

Pañcagranthi by Ācārya Buddhisāgarasūri (10th century) in poetic form, complemented with auto-commentary.[52] Siddha-Hema-Śabdānuśāsana by Acharya Hemachandra (c. 12th century CE) is considered by F. Kielhorn as the best grammar work of the Indian middle ages.[53] Hemacandra's book Kumarapalacaritra is also noteworthy.[54][55] Malayagiri, a contemporary to Hemachandra, also authored a Śabdānuśāsana, accompanied with an auto-commentary.[50]

Tamil grammar is extensively described in the oldest available grammar book for Tamil, the Tolkāppiyam (dated between 300 BCE and 300 CE) whose author was a Jain.[56] S. Vaiyapuri Pillai suggests that Tolkappiyar was a Jain scholar well-versed in the Aintiram grammatical system and posits a later date, placing him in southern Kerala around the 5th century CE. Notably, Tolkappiyam incorporates several Sanskrit and Prakrit loanwords, reflecting its historical and linguistic context.[57]

Another grammatical text Naṉṉūl (Tamil: நன்னூல்) is a work on Tamil grammar written by a Jain ascetic Pavananthi Munivar around 13th century CE. It is the most significant work on Tamil grammar after Tolkāppiyam.[58]

Prākṛta-Lakṣaṇa (The characteristic of Prakrit) is one of the earliest extant specialised grammar of Prakrit. A. F. Rudolf Hoernle opines that the grammar was written by a Jaina author.[59]

Jain acharya Hemchandra also contributed to grammar. He wrote Siddha-Hema-Śabdanuśāśana, which includes six languages: Sanskrit, the "standard" Prakrit (virtually Mahārāṣṭrī Prākrit), Śaurasenī, Māgadhī, Paiśācī, the otherwise-unattested Cūlikāpaiśācī and Apabhraṃśa (virtually Gurjar Apabhraṃśa, prevalent in the area of Gujarat and Rajasthan at that time and the precursor of Gujarati language). He gave a detailed grammar of Apabhraṃśa and also illustrated it with the folk literature of the time for better understanding. It is the only known Apabhraṃśa grammar. He wrote the grammar in the form of rules, with eight adhyayas (chapters) and its auto-commentaries, namely "Tattvaprakāśikā Bṛhadvṛtti" with "Śabdamahārṇava Nyāsa" in one year. Jayasimha Siddharaja had installed the grammar work in Patan's (historically Aṇahilavāḍa) state library. Many copies were made of it, and many schemes were announced for the study of the grammar. Scholars like Kākala Kāyastha were invited to teach it.[60] Moreover, an annual public examination was organized on the day of Jñāna-pañcamī.[61] Kielhorn regards this as best grammar of Indian middle ages.[62]

The German scholar Georg Buhler wrote, "In grammar, in astronomy as well as in all branches of belles letters the achievements of the Jains have been so great that even their opponents have taken notice of them and that some of their work are of importance for European science even today. In the south where they have worked among the Dravidian peoples, they have also promoted the development of these languages. The Kanarese, Tamil, Telugu literary languages rest on the foundations erected by the Jain monks."[63]

Narrative, Poetics, and Puranas

Jaina narrative literature mainly contains stories about sixty-three prominent figures known as Salakapurusa, and people who were related to them. Some of the important works are Harivamshapurana of Jinasena (c. 8th century CE), Vikramarjuna-Vijaya (also known as Pampa-Bharata) of Kannada poet named Adi Pampa (c. 10th century CE), Pandavapurana of Shubhachandra (c. 16th century CE).

Mathematics and Cosmology

Jain literature covered multiple topics of mathematics around 150 CE including the theory of numbers, arithmetical operations, geometry, operations with fractions, simple equations, cubic equations, bi-quadric equations, permutations, combinations and logarithms.[64]

Remove ads

Languages

Summarize

Perspective

The spoken scriptural language is believed to be Magadhi Prakrit by Śvetāmbara Jains, and a form of divine sound or sonic resonance by Digambaras.[5] The Jain Agamas and their commentaries were composed mainly in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit as well as in Maharashtri Prakrit.[47]

Jains literature exists mainly in Jain Prakrit, Sanskrit, Marathi, Tamil, Rajasthani, Dhundari, Marwari, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Telugu[65] and more recently in English.[66]

Jains have contributed to India's classical and popular literature. For example, almost all early Kannada literature and many Tamil works were written by Jains. Some of the oldest known books in Hindi and Gujarati were written by Jain scholars.[citation needed]

The first autobiography in the ancestor of Hindi, Braj Bhasha, is called Ardhakathānaka and was written by a Jain, Banarasidasa, an ardent follower of Acarya Kundakunda who lived in Agra. Many Tamil classics are written by Jains or with Jain beliefs and values as the core subject. Practically all the known texts in the Apabhramsha language are Jain works.[citation needed]

The oldest Jain literature is in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit[67] and the Jain Prakrit (the Jain Agamas, Agama-Tulya, the Siddhanta texts, etc.). Many classical texts are in Sanskrit (Tattvartha Sutra, Puranas, Kosh, Sravakacara, mathematics, Nighantus etc.). "Abhidhana Rajendra Kosha" written by Acharya Rajendrasuri, is only one available Jain encyclodaedic dictionary to understand the technical Jain terms in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit and other languages, with specific reference to Jain literature.[citation needed]

Jain literature was written in Apabhraṃśa (Kahas, rasas, and grammars), Standard Hindi (Chhahadhala, Moksh Marg Prakashak, and others), Tamil (Nālaṭiyār, Civaka Cintamani, Valayapathi, and others), and Kannada (Vaddaradhane and various other texts). Jain versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata are found in Sanskrit, the Prakrits, Apabhraṃśa and Kannada.[citation needed]

Jain Prakrit is a term loosely used for the language of the Jain Agamas (canonical texts). The books of Jainism were written in the popular vernacular dialects (as opposed to Sanskrit), and therefore encompass a number of related dialects. Chief among these is Ardha Magadhi, which due to its extensive use has also come to be identified as the definitive form of Prakrit. Other dialects include versions of Maharashtri and Sauraseni.[19]

Remove ads

Manuscript Heritage and Preservation

Summarize

Perspective

The Jain literary tradition is notable for its large and ancient body of manuscripts.[68] The act of commissioning and donating texts, known as shastra-dana (the "gift of knowledge"), has been a traditional act of religious merit for centuries.[citation needed] This practice, by both ascetics and the laity, led to the accumulation of large manuscript collections, many of which remain unstudied.[69]

The Bhandaras (Knowledge Warehouses)

Jain manuscript libraries, or jñāna bhaṇḍāras ('knowledge warehouses'), are among the oldest surviving libraries in India.[68] They were often housed in temple basements for preservation and managed by the lay community or designated monks.[70]

These bhandaras hold hundreds of thousands of documents, including some of the earliest-known palm-leaf manuscripts from the 11th century.[citation needed] Significant historical collections are located in Patan (Gujarat), Jaisalmer (Rajasthan), and Moodabidri (Karnataka), among others.[citation needed] These collections are a primary source for the literary, religious, and social history of the regions.[citation needed]

Modern Preservation and Digitization

The manuscript collections, written on organic materials like palm leaf and paper, face constant threats from disintegration, moisture, and insect damage.[71] This has led to modern conservation and digitization efforts to preserve the texts.[71]

National and international institutions are involved in this work.[citation needed] For example, the Government of India has supported the establishment of a Centre for Jain Manuscriptology at Gujarat University, a facility dedicated to the conservation, digitization, and research of these manuscripts.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Influence on Indian literature

Summarize

Perspective

Parts of the Sangam literature in Tamil are attributed to Jains. Tamil Jain texts such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār are credited to Digambara Jain authors.[72][73] These texts have seen interpolations and revisions. For example, it is generally accepted now that the Jain nun Kanti inserted a 445-verse poem into Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in the 12th century.[74][75] The Tamil Jain literature, according to Dundas, has been "lovingly studied and commented upon for centuries by Hindus as well as Jains".[73] The themes of two of the Tamil epics, including the Silapadikkaram, have an embedded influence of Jainism.[73] Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain.[76] S. Vaiyapuri Pillai suggests that Tolkappiyar was a Jain scholar well-versed in the Aintiram grammatical system and posits a later date, placing him in southern Kerala around the 5th century CE. Notably, Tolkappiyam incorporates several Sanskrit and Prakrit loanwords, reflecting its historical and linguistic context.[77]

A number of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been found in Tamil Nadu that date from the 3rd century BCE. They are regarded to be associated with Jain monks and lay devotees.[78][79]

Some scholars consider the Tirukkural by Valluvar to be the work by a Jain.[80][81][82] It emphatically supports moral vegetarianism (Chapter 26) and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than a thousand offerings in fire (verse 259).[83][84]

Silappatikaram, a major work in Tamil literature, was written by a Samaṇa(jain), Ilango Adigal. It describes the historical events of its time and also of the then-prevailing religions, Jainism, and Shaivism. The main characters of this work, Kannagi and Kovalan, who have a divine status among Tamils, were Jains.

According to George L. Hart, the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies" was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai:

There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 CE in Maturai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the cangkam legend."[85]

Jainism began to decline around the 8th century, with many Tamil kings embracing Hindu religions, especially Shaivism. Still, the Chalukya, Pallava and Pandya dynasties embraced Jainism.

Jain scholars also contributed to Kannada literature.[86] The Digambara Jain texts in Karnataka are unusual in having been written under the patronage of kings and regional aristocrats. They describe warrior violence and martial valor as equivalent to a "fully committed Jain ascetic", setting aside Jainism's absolute non-violence.[87]

Jain manuscript libraries called bhandaras inside Jain temples are the oldest surviving in India.[88] Jain libraries, including the Śvētāmbara collections at Patan, Gujarat and Jaiselmer, Rajasthan, and the Digambara collections in Karnataka temples, have a large number of well-preserved manuscripts.[88][89] These include Jain literature and Hindu and Buddhist texts. Almost all have been dated to about, or after, the 11th century CE.[90] The largest and most valuable libraries are found in the Thar Desert, hidden in the underground vaults of Jain temples. These collections have witnessed insect damage, and only a small portion have been published and studied by scholars.[90]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads