Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

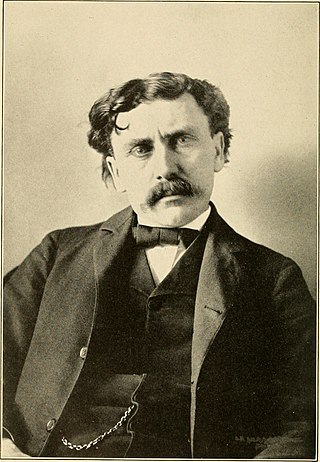

James Mooney

American ethnographer (1861–1921) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who worked for the Bureau of American Ethnology for thirty-six years and studied North American, particularly the Kiowa, Cheyenne and Cherokee tribes. He lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man",[1] he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Great Plains.[2] He did ethnographic studies of the Ghost Dance, a spiritual movement among various Native American culture groups, after Sitting Bull's death in 1890. His works on the Cherokee include The Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees (1891), and Myths of the Cherokee (1900). All were published by the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, within the Smithsonian Institution.

Native American artifacts collected by Mooney are held in the collections of the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution[3] and the Department of Anthropology, Field Museum of Natural History.[4] Papers and photographs from Mooney are in the collections of the National Anthropological Archives, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution.[5][6]

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

James Mooney was born on February 10, 1861, in Richmond, Indiana. He was the son of Irish Catholic immigrants, James Mooney Sr. and Ellen Devlin. His parents came from farming families in County Meath.[1]: 2 They left for Liverpool around 1849 and then migrated to New York in 1852. That same year, they were married at the Little Church of the Transfiguration in New York City. Their first child, Mary Anne, was born in 1853. The family soon moved to Richmond, Indiana, where James Mooney Sr. worked at a local gas station.[7]: 3 Their next daughter, Margaret, was born in 1856. A few years later, Ellen gave birth to their son, James Mooney. James Mooney Sr. died of pneumonia when his son was only a few months old.[8]: 35

Mooney's mother raised her children Catholic, sending them to St. Mary's Catholic Church for religious education. Mooney and his siblings were also brought up learning about their Irish roots through their mother and grandmother's stories about Irish folklore, history and traditions.[1]: 3 His sister Mary Anne would grow up to become a nun at Mount St. Clare Convent, while his other sister Margaret would remain a schoolteacher throughout her life.[1]: 4

As a child, Mooney was frequently left feeling weak due to his rheumatic fever, an illness which would pose difficulties for him throughout his adult life as well.[7]: 5 Since he was young, Mooney’s family and teachers had noted his studious nature. Mooney was known to go through obsessive phases. At eight years of age, he began a project to document all the books that had ever been published. Later on, he would also try to make a list of all the different types of sewing machines and all the insurance companies doing business at the time. In 1873, Mooney discovered his lifelong interest in Indians in the aftermath of the Modoc War, after hearing someone make a comment about it. He was 12 years of age at the time, and resolved to compile a list of the names and locations of all existing Native American tribes.[7]: 5

Mooney's formal education was limited to the public schools of the city, and he graduated from Richmond High School in May 1879.[9]: ix After graduation, Mooney became a schoolteacher for two semesters. In 1979, he joined the Richmond Palladium as a staff member but continued to devote his extra time to studying Native American cultures. He also increased his knowledge of Indian anthropology by studying the works of John Wesley Powell and Lewis Henry Morgan.[7]: 5 While in Richmond, Mooney lived in close proximity to Earlham College, which allowed him to meet people who were involved in Indian affairs. During this period, Mooney was also able to meet with some Indians themselves as many of them attended Quaker missionary schools in the area.[8]: 35 He spent his time in Earlham's library to read books about Indians and study his interests in more depth. He became a self-taught expert on American tribes by his own studies and his careful observation during long residences with different groups. The field of ethnography was new in the late 19th century, and he helped create high standards for the work.[2]

Remove ads

Career at the Bureau of American Ethnology

Summarize

Perspective

In 1885, Mooney started working with the Bureau of American Ethnology (now part of the Smithsonian Institution) at Washington, D.C., after years of written correspondence with John Wesley Powell to convince him of his qualifications. It was not until Mooney traveled to Washington in 1885 to personally meet with Powell and show him samples of his work that Powell allowed Mooney to work at the bureau as a volunteer.[7]: 7

Mooney's first major assignment was to classify Native American tribes by linguistic categories. Mooney had previously already compiled a list of approximately 2,500 tribal names, which he referred to as his "Indian Synonymy."[8]: 43-44 Powell assigned Henry Weatherbee Henshaw to assist Mooney in revising his synonymy. The final list was published as a 55-page booklet under the title A List of Linguistic Families of the Indian Tribes North of Mexico, with Provisional List of the Principal Tribal Names and Synonyms.[8]: 44 This work became an essential manual for the bureau until a more comprehensive classification appeared in 1891 under Powell’s name.

Mooney was then given a second assignment to build upon the work of Otis T. Mason, the curator of ethnology at the National Museum since 1884. The task was to review the bureau’s library to determine its usefulness for ethnological research and create thorough files on Indian tribes by their linguistic affinity. Under Henshaw, who assigned several staff members to each linguistic group, Mooney, alongside Garrick Mallery, expanded on his original synonymy project and focused on the Algonquian and Iroquoian families.[10]: 19

After officially being sworn in as an ethnologist by the bureau in 1886, Mooney decided to embark on his first fieldwork among the Eastern band of the Cherokee, mostly in North Carolina. He worked closely with them for three consecutive seasons from 1887 to 1889, learning their language and daily life while collecting enough material to produce several important ethnographic studies.[8]: 66 The extended length of time he spent amongst them allowed him to document sacred narratives, ritual practices, and historical traditions that were rarely shared with outsiders.[11]: 22 This culminated in one of his most acclaimed publications, Myths of the Cherokee (1900).

In the fall of 1890, Mooney was on his way to conduct fieldwork for his research on the Cherokee, authorized by the bureau, when the Ghost Dance began to draw public attention. He asked the bureau for permission to go observe the Ghost Dance instead, and was awarded it with the additional task of investigating the phenomenon thoroughly.[12]: xi His book, The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890 (1896) included a balanced historical account drawing on unpublished government records, newspaper reports, and interviews with Native American people. Mooney’s analysis was different from most of his contemporaries' analysis as he treated the Ghost Dance as a legitimate religious response to colonial dispossession rather than as a political conspiracy or delusion.[12]

In his later bureau career, Mooney devoted increasing attention to the peyote religion.[11]: 179–205 He viewed peyotism as one of the most significant Indigenous religious developments of the modern period and sought to document it comprehensively. His work in this area, however, caused him trouble with federal Indian policy and led him to be met with suspicion and doubt by government institutions.[11]: 86

Remove ads

Writing career

Summarize

Perspective

Mooney's writing style was widely considered as evocative. His sympathetic treatment of Native Americans is attributed to his upbringing and ethnic heritage. Although he wrote as a scientist, his objective attitude toward Native Americans contrasted with other writing, which was often either romantic or discriminatory. He largely accepted the goal of Indian assimilation as outlined by reformers of the era. But, he was a witness to what the costs were to the traditional peoples and reported on issues and changes with objectivity.[1]

During the late 1800s Native Americans were under harsh attack in many areas, and essentially subjects of genocide by the United States of America. The Indian Wars, intended to suppress tribal resistance to European-American settlement of the West, was generally presented as required because Native Americans made unjustified attacks on pioneers. Mooney wrote more objectively about issues in the West.

Mooney took the time to observe various Native American tribes in the way they lived on a daily basis. Prior to his work, most people outside reservations learned about issues only from a distance. He wanted to learn and to teach other Americans about their culture. He published several books based on his studies of Native American tribes.

The Ghost-dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890

Mooney spent twenty-two months living among roughly twenty Plains tribes. His ethnographic writing provides a preface with a historical survey of comparable millenarian movements among other American Indian groups. In response to the rapid spread of the Ghost Dance among tribes of the western United States in the early 1890s, Mooney set out to describe and understand the phenomenon. He visited Wovoka, the Ghost Dance prophet, at his home in Nevada. He also traced the movement of the Ghost Dance from place to place, describing the ritual and recording the distinctive song lyrics of seven separate tribes.[12] In his book, Mooney gave a vivid and detailed picture of a major revitalization movement and showed that the Ghost Dance is an Indian nativist movement which shared key similarities with other cultural renewal efforts and religions found across many societies, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.[12]: v Mooney compares Wovoka and his Ghost Dance to Messianic themes found in other religions and writes:

The doctrines of the Hindu avatar, the Hebrew Messiah, the Christian millennium, and the Hesunanin of the Indian Ghost dance are essentially the same, and have their origin in a hope and longing common to all humanity.[12]: 1

He argued that the Ghost Dance was meant to help Native American people cope with forced cultural change, not threatening war, as government agents and newspapers had claimed.

The second part of the text also investigated the background to and circumstances which resulted in the massacre of Indians at Wounded Knee in South Dakota in December 1890.[12]

Criticism and Backlash

Some of Mooney's contemporaries such as Samuel Langley, who was director of the Smithsonian at the time, thought that Mooney was taking up a risky endeavor by using a comparative lens to depict the Ghost Dance and its shared similarities with other religions. He believed Mooney's work would expose the bureau to criticism. Langley wrote to Powell that Mooney’s thoughts “had better have been left unwritten."[1]: 91

Professor of English, Michael A. Elliot, also calls out the internal contradictions of Mooney's approach. Elliot argues that Mooney attempts to uncover the Ghost Dance and its history through a sympathetic lens but in downplaying the Ghost Dance's militant nature or cry for change, the Ghost Dance is instead reduced to harmless religious reaction and not treated as a serious enough political response to colonial oppression. By framing it mainly as a spiritual revival caused by hunger, stress, and cultural loss, he downplayed Indigenous agency and resistance demanding a different future.[13]

Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians (1898)

"The desire to preserve to future ages the memory of past achievements is a universal human instinct,"Mooney said. "The reliability of the record depends chiefly on the truthfulness of the recorder and the adequacy of the method employed."[14] Mooney earned the confidence of the Kiowa who told him about their system of calendars to record events. They told him that the first calendar keeper in their tribe was Little Bluff, or Tohausan, principal chief of the tribe from 1833 to 1866. Mooney also worked with two other calendar keepers, Settan, or Little Bear; and Ankopaingyadete, meaning "In the Middle of Many Tracks", and commonly known as Anko. Other Plains tribes kept pictorial records, which are known as winter counts. They were commonly created in the winter, when the people were indoors, and expressed major events of the year.

The Kiowa recorded two events for each year, offering a finer-grained record and twice as many entries for any given period. Silver Horn (1860–1940), or Haungooah, was the most highly esteemed artist of the Kiowa tribe in the 19th and 20th centuries, and kept a calendar. He was a respected religious leader in his later years.[14]

Myths of the Cherokee (1900)

Mooney also spent much time with the Cherokee, by then removed to Indian Territory (in what is now Oklahoma and North Carolina). For many years he worked with Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians elder and translator Will West Long.[15] He studied their language, culture, and mythology. This comprehensive volume compiled 126 Cherokee myths, including sacred stories, animal myths, local legends, wonder stories, historical traditions, and miscellaneous myths and legends. Some myths included:

- How the World was Made

- Why the Deer's Teeth are Blunt

- How the Turkey got his Beard

- Why the Possum's Tail is Bare

The book also includes original Cherokee manuscripts, relating to the history, archaeology, geographic nomenclature, personal names, botany, medicine, arts, home life, religion, songs, ceremonies, and language of the tribe.[16]

The Sacred Formulas of The Cherokee (1891)

Mooney conducted his fieldwork for this publication in an Indian reservation among the North Carolina Cherokee between 1887 and 1888. The Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees is a smaller piece compared to its predecessor, Myths of the Cherokee. It is a succinct description of twenty-eight ritual formulas regarding the subjects of "medicine, love, hunting, fishing, war, self-protection, destruction of enemies, witchcraft, the crops, the council, the ball play, etc.,"[17]: 308 presented in the original Cherokee. It uses Sequoyah typography and is accompanied by an English translation and explanation. Mooney candidly discusses the difficulties obtaining these materials, the reluctance of his informants to make this information public.

Some critics question whether publishing these sacred chants violated the privacy of the people Mooney studied. They argue that sharing ritual material raises ethical concerns about an ethnographer’s responsibility to respect Indigenous beliefs.[18]

Historical Sketch of the Cherokee (1975)

Published posthumously, this account of the Cherokee started with their first contact with whites and, through battles won and lost, treaties signed then broken, towns destroyed and people massacred, ended around 1900. There is humanity along with inhumanity in the relations between the Cherokee and other groups, Indian and non-Indian; there is fortitude and persistence balanced with disillusionment and frustration. In these respects, the history of the Cherokee epitomizes the experience of most Native Americans,[19] Mooney writes. This, among with most, if not all of Mooney's works, is considered dispassionate and matter-of-fact, which is why his works are found in the Bureau of American Ethnology.

Remove ads

Collections

Summarize

Perspective

Mooney curated many collections and displays during his lifetime. The Smithsonian has also preserved a James Mooney collection since his passing, which contains "field notes, drawings, maps, letters, historical research, and writings related to his research work as Ethnologist for the Bureau of American Ethnology from 1887 to 1922."[20]

- 1891: Commissioned model tipis and summer houses from the Kiowa

- 1892: Began intensive field study of Kiowa winter counts and Kiowa heraldry Worked among the Navajo and Hopi, making collections for the World's Columbian Exposition

- 1892: Mooney collected material and prepared exhibits for the Spanish-Columbian Exposition in Madrid, Spain

- 1893: Curated World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois

- 1897: Prepared an exhibit for Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition in Nashville, Tennessee

- 1898: Prepared an exhibit for Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska

- 1901 - 1906: Entered into cooperative agreement between the BAE and the Field Museum; Studied and collected Kiowa for the BAE/USNM and studied and collected Cheyenne for the Field Museum

- 1903: Visited the Cheyenne-Arapaho agency in Darlington; finished Kiowa tipi models for the BAE's exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

- 1904: Supervised the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri.

Remove ads

Peyote Controversy and Ban on Fieldwork

Summarize

Perspective

In the 1870s, a new religion developed among Native Americans living on reservations in western Indian Territory, which involved the ritual consumption of peyote. Peyote is a small cactus without any spines that causes visual and auditory hallucinations when eaten. In 1890, the Bureau of Indian Affairs banned peyotism in 1890, stating that it was a harmful drug.[21] Mooney, who had been conducting research on peyote consumption since the early 1890s, was a strong supporter of the religion and defended it when Congress attempted to take action against its practitioners.[21]

In 1914, the Mohonk Conference held a session supporting the criminalization of Peyote.[1]: 181 After hearing about the conference proceedings, Mooney penned a reply to its secretary, defending peyotism: “I find several devoted to peyote, in which the whole tone is violently denunciative of the plant and the rite.”[22]: 182 Mooney presented his qualifications as someone who had spent time studing peyote consumption and its participants in details, and wrote that the plant did not foster immorality or affect one's lifespan. Rather, he wrote, the opposition to peyotism was simply based on ignorance.[22]: 182

Mooney later testified in front of the U.S. House of Representatives to combat the move to ban peyotism. Due to his speech, those in favor of peyote consumption were able to win the vote. In 1918, Mooney traveled to Oklahoma to help start the Native American Church.[23]: 9 However, Mooney's activism was not appreciated and that same year, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs banned Mooney from conducting fieldwork on any Indian reservations.[7]: 7

Remove ads

Personal life and death

Summarize

Perspective

He married Ione Lee Gaut, a native of Cleveland, Tennessee, on September 28, 1897, in Washington, D.C., and had six children. Mooney's wife would accompany him on multiple work related trips and prepared even prepared a bibliography for some of his printed works.[16]: 7 One of their sons was the writer Paul Mooney. The two also had three daughters, one of them named Alicia Howard Mooney. [24]: 194 After battling a long illness, Mooney died of heart disease in Washington, D.C., on December 22, 1921. He was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Ties to Irish-Catholic Background

While proud of his Irish roots, Mooney had a complicated relationship with Catholicism. During his years at the bureau, Mooney would occasionally be referred to as the “anthropological Irishman.”[25]: 20 In 1880, he was one of the organizers of the Richmond branch of the American Land League.[26]: 52 He was also the president of the Gaelic Society of Washington, D.C., established in 1907.[26]: 53

Mooney grew up regularly attending Church regularly but, as an adult, he did not attend mass a lot and turned his back on the Catholic Church. He also rarely attended religious celebrations or received the Church's sacraments.[26]

Remove ads

Legacy

James Mooney is now recognized as one of the most important ethnologists in early American anthropology. He was notable for his approach of understanding Native American cultures on their own terms, which marked a key shift toward modern ethnographic methods.

To honor his legacy, the Southern Anthropological Society established the annual James Mooney Award. According to the society, the award recognizes texts that maintain high standards of quality, clear thinking, and engaging writing. It celebrates Mooney as a dedicated ethnologist who advanced anthropology with both scientific rigor and deep sympathy. He was known for his thorough and professional study of American Indian cultures.[27]: 234

Remove ads

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

- Mooney, James. Linguistic families of Indian tribes north of Mexico, with provisional list of principal tribal names and synonyms.[28] U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1885.

- Mooney, James. The Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1885-6 Annual Report, 1891.

- Mooney, James. Siouan tribes of the East. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 1894.

- Mooney, James. The Ghost-dance religion and the Sioux outbreak of 1890. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1892-3 Annual Report, 2 vols., 1896.

- Mooney, James. Calendar history of the Kiowa Indians. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1895-6 Annual Report, 1898.

- Mooney, James. Myths of the Cherokee. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1897-8 Annual Report, 1902.

- Mooney, James. Indian missions north of Mexico. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 1907.

- Mooney, James. The Swimmer manuscript: Cherokee sacred formulas and medicinal prescriptions, revised, completed and edited by Frans M. Olbrechts, 1932.

- Mooney, James, 1861–1921. "James Mooney's history, myths, and sacred formulas of the Cherokees :containing the full texts of Myths of the Cherokee (1900) and The sacred formulas of the Cherokees (1891) as published by the Bureau of American Ethnology : with a new biographical introduction.

- Ellison, George, James Mooney and the eastern Cherokees, Asheville, NC: Historical Images, 1992.

Full etexts of many of the above are available at archive.org[29]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads