Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

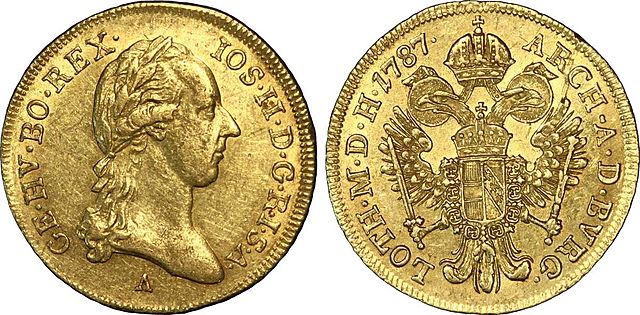

Joseph II (13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from 18 August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 29 November 1780 until his death. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Emperor Francis I, and the brother of Marie Antoinette, Leopold II, Maria Carolina of Austria, and Maria Amalia, Duchess of Parma. He was thus the first ruler in the Austrian dominions of the union of the Houses of Habsburg and Lorraine, styled Habsburg-Lorraine.

Joseph was a proponent of enlightened absolutism like his brother Leopold II; however, his commitment to secularizing, liberalizing and modernizing reforms resulted in significant opposition, which resulted in failure to fully implement his programs. Meanwhile, despite making some territorial gains, his reckless foreign policy badly isolated Austria. He has been ranked with Catherine the Great of Russia and Frederick the Great of Prussia as one of the three great Enlightenment monarchs. False but influential letters depict him as a somewhat more radical philosophe than he probably was. His policies are now known as Josephinism. He was a supporter of the arts, particularly of composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri. He died with no known surviving legitimate offspring and was succeeded by his younger brother Leopold II.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Joseph II was a son of Maria Theresa and Francis I. He was born on Monday, March 13, 1741, at two in the morning, in Vienna's Hofburg, the Habsburg dynasty's principal house and administrative center. The following day, Joseph Benedict Augustus Johann Anton Michael Adam was baptized by the papal nuncio with the help of no fewer than sixteen other prelates. The godfathers, Pope Benedict XIV and Polish King Augustus III, were represented by delegates.[1] He had 15 siblings of whom 6 died before their adolescence.[2]

Education

Joseph II received a comprehensive and carefully structured education befitting his status as Maria Theresa's eldest son and heir. Joseph's early education was supervised by a group of distinguished teachers selected by Maria Theresa, including, most notably, Pater Anton von Weger and Karl Joseph Batthyány serving as Joseph’s Hofmeister who were entrusted with overseeing his education. In addition to these principal figures, several other tutors played important roles in Joseph’s education. Johann Wilhelm Höller Franz and Bernhard Weickhart were responsible for instruction in Latin and classical studies, providing a foundation in historical and philosophical texts. Jean Bréquin, a Frenchman, was tasked with teaching Joseph mathematics.[3] A great deal of his education focused on history, taught by State Secretary Christoph von Bartenstein.[4]

Remove ads

Marriages and children

Summarize

Perspective

Despite being an inevitable political arrangement, Joseph's marriage, which occurred when he was nineteen, ended up being a pleasant one for the duration. The marriage was linked to the Diplomatic Revolution, also known as the Austro-French Alliance of 1756. The stunning Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV's mistress, and Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz, the Austrian chancellor, collaborated on it. Louis XV proposed that Joseph, the infant heir to the Austrian throne, wed his granddaughter Isabella of Parma in order to solidify this Habsburg-Bourbon alliance. Joseph, who admired Isabel's appearance when he saw her portrait, was also thrilled, as did Maria Theresa. The wedding was lavishly celebrated in June 1760. The service was conducted at the Augustinian church by Borromeo, the papal legate.[5]

The marriage of Joseph and Isabella resulted in the birth of a daughter, Maria Theresa. Isabella was fearful of pregnancy and early death, largely a result of the early loss of her mother. Her own pregnancy proved especially difficult as she suffered from pregnancy depression, though Joseph attended to her and tried to comfort her. [6]

In 1763 Isabella fell ill with smallpox and went into premature labor, resulting in the birth of their second child, Archduchess Maria Christina (b.d November 22, 1763), who died shortly after being born. Isabella died soon afterwards. The loss of his beloved wife and their newborn child was devastating for Joseph, after which he felt keenly reluctant to remarry.[7]

For political reasons, and under constant pressure, in 1765, he relented and married his second cousin, Princess Maria Josepha of Bavaria, the daughter of Charles VII, Holy Roman Emperor, and Archduchess Maria Amalia of Austria. Though Maria Josepha loved her husband, she felt timid and inferior in his company. Lacking common interests or pleasures, the relationship offered little for Joseph, who confessed he felt no love (nor attraction) for her in return. He adapted by distancing himself from his wife to the point of near total avoidance, seeing her only at meals and upon retiring to bed. Maria Josepha, in turn, suffered considerable misery in finding herself locked in a cold, loveless union. Four months after the second anniversary of their wedding, Maria Josepha grew ill and died from smallpox. Joseph neither visited her during her illness nor attended her funeral, though he later expressed regret for not having shown her more kindness, respect, or warmth. One thing the union did provide him was the improved possibility of laying claim to a portion of Bavaria, though this would ultimately lead to the War of the Bavarian Succession. Joseph never remarried.[8]

Remove ads

Co-ruler

Summarize

Perspective

Joseph was made a member of the constituted council of state (Staatsrat) and began to draw up minutes for his mother to read. These papers contain the germs of his later policy, and of all the disasters that finally overtook him. He was a friend to religious toleration, anxious to reduce the power of the church, to relieve the peasantry of feudal burdens, and to remove restrictions on trade and knowledge. In these, he did not differ from Frederick, or his own brother and successor Leopold II, all enlightened rulers of the 18th century.[9] He tried to liberate serfs, but that did not last after his death.[10]

Where Joseph differed from great contemporary rulers, and was akin to the Jacobins in the intensity of his belief in the power of the state when directed by reason. As an absolutist ruler, however, he was also convinced of his right to speak for the state uncontrolled by laws, and of the wisdom of his own rule. He had also inherited from his mother the belief of the House of Austria in its "August" quality and its claim to acquire whatever it found desirable for its power or profit. He was unable to understand that his philosophical plans for the moulding of humanity could meet with pardonable opposition.[11][9]

Joseph was documented by contemporaries as being impressive, but not necessarily likable. In 1760, his arranged consort, the well educated Isabella of Parma, was handed over to him. Joseph appears to have been completely in love with her, but Isabella preferred the companionship of Joseph's sister, Marie Christine of Austria. The overweening character of the Emperor was obvious to Frederick II of Prussia, who, after their first interview in 1769, described him as ambitious, and as capable of setting the world on fire. The French minister Vergennes, who met Joseph when he was traveling incognito in 1777, judged him to be "ambitious and despotic".[12][13] In August 1765 his father died after a seizure. In a letter to his former tutor Batthyany, Joseph — now automatically becoming emperor — expressed sorrow and self-pity at the death of his father.[14]

He was my teacher, my friend . . . I am now twenty-four years of age. Providence has given me the cup of sorrow in my early days. I lost my wife after having possessed her scarcely three years. Dear Isabel! thou wilt never be forgotten by me! You, my prince, were the guide of my youth; under your direction I became a man. Do now support me also as a monarch in the important duties which destiny imposes upon me, and preserve your heart for your friend.

As emperor, the nominal head of the venerable but inert institution known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation he had little true power. Joseph was only allowed to have as much power during his mother's lifetime as Maria Theresa, the Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Bohemia and Hungary, felt comfortable giving him. The actual power was held by Maria Theresa, who ruled the Austrian hereditary dominions. Maria Theresia took the extraordinary decision to make her son co-regent because she felt she could no longer continue running the government alone. Joseph had no power save in the army, treasury, and court administration. This was limited, though, as his mother had the last say on all significant issues. Although Joseph had a little more influence in military matters, he prudently avoided using it since he was aware of his mother's rage and always showed deference to his mother's superior.[15]

As co-regent alongside his mother, Empress Maria Theresa, from 1765 onward, Joseph II quickly became involved in the financial administration of the Habsburg Monarchy, recognizing the urgent need to reform and rationalize the state and court budget. The Austrian fiscal system at the time was notoriously inefficient and weighed down by the costs of maintaining a sprawling imperial court, a vast bureaucracy, and a large standing army. Joseph, influenced by Enlightenment ideals of efficiency and utility, advocated for a more centralized and accountable approach to public finance.[16]

One of his first priorities was to gain a clearer understanding of the monarchy’s financial state, which had long been obscured by a patchwork of regional accounts and a lack of standardized procedures. Joseph pressed for the creation of more systematic and transparent bookkeeping practices, insisting on detailed and regular financial reports from court and government departments. He also sought to reduce unnecessary expenditure at court, curbing lavish spending on ceremonies, festivities, and personal privileges that had characterized the reign of his father, Francis I, and earlier Habsburg rulers.[16]

Joseph initiated reductions in the size and costs of the imperial household, cut down on the number of court officials and servants, and attempted to limit the extravagance of court life. He championed the idea that the monarchy should serve the state, not vice versa, and that royal resources were to be used for the common good rather than for personal luxury. Furthermore, Joseph advocated for the reform of tax collection, pushing for a more equitable distribution of the tax burden and greater efficiency in revenue gathering. [16] In the mid-18th century, the Jesuit order had become a target of suspicion and criticism throughout Europe, seen by many rulers as too independent, too influential in education, and insufficiently loyal to secular authority. Joseph shared these Enlightenment-inspired concerns and regarded the Jesuits as a barrier to modernizing reforms, particularly in education and church-state relations. When Pope Clement XIV formally dissolved the Society of Jesus in 1773, the Habsburg Monarchy, under Maria Theresa’s rule with Joseph’s strong encouragement, moved quickly to implement the papal brief. Joseph had already been pressing for greater state control over education and religious institutions, and the papal suppression provided the perfect opportunity.[17]

As Josephs power become more and more cemented he focused on foreign affairs. Joseph played a key role in the negotiations and the subsequent integration of Galicia into the Habsburg Monarchy the First Partition of Poland in 1772.[18] His co-regency period also saw important legal and educational reforms initiated under Maria Theresa’s leadership, with Joseph’s support. The 1774 General School Ordinance (Allgemeine Schulordnung) established a standardized, state-controlled school system, reflecting Enlightenment ideals about education and citizenship.[19]

During these years, Joseph traveled much. He met Frederick the Great privately at Neisse in 1769 (later painted in The Meeting of Frederick II and Joseph II in Neisse in 1769), and again at Mährisch-Neustadt in 1770; the two rulers initially got along well. On the second occasion, he was accompanied by Prince Kaunitz, whose conversation with Frederick may be said to mark the starting point of the First Partition of Poland. To this and to every other measure which promised to extend the dominions of his house, Joseph gave hearty approval.[20] Thus, when Frederick fell severely ill in 1775, Joseph assembled an army in Bohemia which, in the event of Frederick's death, was to advance into Prussia and demand Silesia (a territory Frederick had conquered from Maria Theresa in the War of the Austrian Succession). However, Frederick recovered, and thereafter became wary and mistrustful of Joseph.[21]

A crisis that threatened a resumption of the great conflicts between Prussia and Austria was brought on by the sudden death of Maximilian Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, in December 1777. It had long been clear that the Bavarian house's male line was destined to disappear, and the Austrian court had been quietly formulating plans to acquire significant territory when the succession issue arose. In order to bridge the gap between Bohemia and the southern provinces of the Austrian empire, it was most desirable to have Bavaria, or at least a piece of it, and it appeared that colorable claims might be made to a sizable chunk of the empty inheritance. The unfortunate second marriage of the young emperor had been arranged primarily to secure this benefit. The Empress Josepha's untimely death in 1766 had put things back in their previous order, and while Maximilian focused his efforts on preserving the integrity of his dominions after his passing, Joseph—who was always a willing student when it came to territorial expansion—kept developing their aggressive plans.[22]

Joseph’s ambitions alarmed Frederick the Great of Prussia, who feared a shift in the balance of power. When Austria moved to occupy parts of Bavaria, Prussia responded by mobilizing its army, and the two powers prepared for war. Maria Theresa was much more cautious and deeply opposed to the prospect of a major conflict, but Joseph pressed aggressively for territorial gains, personally leading the diplomatic negotiations and military planning. When war broke out in 1778, Joseph took command of the Austrian army in the field, joining the troops in Bohemia. However, the campaign quickly bogged down into a war of maneuver and attrition, with little actual fighting—hence its nickname, the "Potato War," as both armies spent more time trying to secure supplies than engaging in battle. Joseph’s logistical and organizational limitations became evident, and his hopes for a swift, glorious conquest faded amid stalemate and mounting costs.[22]

Throughout the crisis, Joseph’s mother worked tirelessly behind the scenes to limit the damage. Maria Theresa maintained secret correspondence with Frederick the Great and sought a diplomatic solution, fearing that a protracted war would weaken the monarchy and risk losing more than it gained. Ultimately, her efforts—supported by the mediation of France and Russia—prevailed. The conflict was resolved by the Treaty of Teschen in 1779, which granted Austria only a small strip of territory (the Innviertel) but forced Joseph to abandon his greater ambitions in Bavaria.[23]

Remove ads

Sole reign

Summarize

Perspective

Domestic policy

The death of Maria Theresa on 29 November 1780 left Joseph free to pursue his own policy, and he immediately directed his government on a new course, attempting to realize his ideal of enlightened despotism acting on a definite system for the good of all.[20] He undertook the spread of education, the secularization of church lands, the reduction of the religious orders and the clergy, in general, to complete submission to the lay state, the issue of the Patent of Toleration (1781) providing limited guarantee of freedom of worship, and the promotion of unity by the compulsory use of the German language (replacing Latin or in some instances local languages)—everything which from the point of view of 18th-century philosophy, the Age of Enlightenment, appeared "reasonable". He strove for administrative unity with characteristic haste to reach results without preparation. Joseph carried out measures of the emancipation of the peasantry, which his mother had begun,[20] and abolished serfdom in 1781.[24] After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Joseph sought to help the family of his estranged sister Queen Marie Antoinette of France and her husband King Louis XVI. Joseph kept an eye on the development of the revolution, and became actively involved in the planning of a rescue attempt. These plans failed, however, either due to Marie Antoinette's refusal to leave her children behind in favor of a faster carriage or Louis XVI's reluctance to become a fugitive king.

Administrative policies

When Maria Theresa died, Joseph started issuing edicts, over 6,000 in all, plus 11,000 new laws designed to regulate and reorder every aspect of the empire. The spirit of Josephinism was benevolent and paternal. He intended to make his people happy, but strictly in accordance with his own criteria.

Joseph set about building a rationalized, centralized, and uniform government for his diverse lands, a hierarchy under himself as a supreme autocrat. The personnel of government was expected to be imbued with the same dedicated spirit of service to the state that he himself had. It was recruited without favor for a class or ethnic origins, and promotion was solely by merit. To further uniformity, the emperor made German the compulsory language of official business throughout the Habsburg Monarchy, which affected especially the Kingdom of Hungary.[25] The Diet of Hungary was stripped of its prerogatives, and not even called together.

As privy finance minister, Count Karl von Zinzendorf (1739–1813) introduced a uniform system of accounting for state revenues, expenditures, and debts of the territories of the Austrian crown. Austria was more successful than France in meeting regular expenditures and in gaining credit. However, the events of Joseph II's last years also suggest that the government was financially vulnerable to the European wars that ensued after 1792.[26]

The Emperor also attempted to simplify the administration of his dominions, often a patchwork of states united in personal union by the Habsburg monarch. As an example, in 1786 he abolished the separate administration of the Duchy of Mantua, merging it with the neighbouring Duchy of Milan. Local opposition to the change forced his successor Leopold II to reverse this measure and restore the duchy in 1791.

Legal reform

Joseph II’s reforming spirit went far beyond simply tweaking the punishment system—he sought nothing less than a thorough overhaul of the entire legal structure. During his years as co-regent, he encouraged outspoken critics of the existing Theresiana code, such as Prince Kaunitz and Baron Binder, who argued that the piecemeal revisions of the old Roman law were hopelessly outdated and that Austria needed a completely new legal framework. When Maria Theresa died in 1780, Joseph seized the chance to act on these ideas in earnest.

Initially, Joseph aimed for a total transformation of both criminal and civil law, but he soon realized the sheer complexity of such an undertaking made it impractical even for a ruler with his energy and determination. Within his first year as sole ruler, Joseph concluded that a more realistic path was to systematically organize and compile the current laws, supplementing them with fresh legislation and targeted procedural reforms in the courts. While the comprehensive legal codification would take time, Joseph immediately set about implementing procedural changes.[27]

These intentions were first laid out in his 1781 directive, the Allgemeine Gerichtsordnung. Joseph kept the Oberste Justizstelle as the empire’s supreme court, making it independent from administrative bodies and answerable only to the emperor himself. To improve efficiency and professionalism, he reduced the number of lower courts and required all judges to have completed university-level legal studies. The number of appellate courts was also cut down to just six for the entire realm. Judges were instructed to adhere strictly to the written law and consult the higher court whenever legal ambiguities arose.[27]

Joseph also restructured the classification of crimes. Serious offenses were now labeled simply as Verbrechen, while less severe infractions, called politische Verbrechen, confusingly adopted a term previously reserved for grave political crimes under Maria Theresa. Punishments for these lesser offenses included beatings, public shaming in the stocks, or deportation, and imprisonment terms for such crimes were capped at one year. Major offenders were to be held in prisons, while special courts, except those for military personnel, were dissolved. Joseph also abolished noble privileges in court, insisting on equality before the law for all social classes.[27] Interestingly, Joseph restored some harsh penalties that had been abolished earlier, such as branding lifelong prisoners or fastening them to cell walls with iron. He also separated crimes against the state—Staatsverbrechen—into their own category, covering offenses like treason, counterfeiting, and crimes against the sovereign. These cases were assigned directly to appellate courts for trial, bypassing the lower courts altogether. Once Joseph had resolved this, he shifted his focus back to a longstanding concern of his: the use of capital punishment. In a confidential directive issued in August 1783, he ruled that, while the death penalty would officially remain part of the law, in practice it would rarely, if ever, be implemented.[27]

Instead, after the sentence was pronounced in court, it would be automatically commuted to imprisonment—unless Joseph himself made an exception. At the same time, he changed the prior limit on prison sentences set by the Theresiana code, making the maximum term indefinite except in cases where a death sentence was commuted. According to Prince Kaunitz, who was well-placed to observe the Emperor’s thinking, Joseph’s motivation was neither a desire to follow Enlightenment philosophers nor a particular aversion to executions; rather, he believed that harsh conditions in prison would serve as a stronger deterrent to crime than the threat of execution.[27]

The commission tasked with reforming the criminal code, which was at first supposed to draft a completely new law but was later told just to revise the Theresiana, worked nearly as slowly as the earlier commission under Maria Theresa. It was not until January 1787 that the new Allgemeines Gesetzbuch über Verbrechen und deren Bestrafung (General Code of Crimes and Punishments) was finally published. This comprehensive document marked both progress and retreat compared to its predecessor: while it effectively abolished the death penalty, it introduced a variety of new measures designed to make imprisonment particularly unpleasant.[27]

Monetary fines, once common for lesser offenses, were largely eliminated in favor of police detention or forced labor, such as street cleaning. The principle of nullum crimen sine lege—no crime without a law—became the basis for all criminal proceedings. However, the practice of allowing legal counsel for the accused was discontinued, as Joseph argued that it was the judge’s responsibility to consider the possibility of a defendant’s innocence and to seek the truth above all else. Additionally, certain crimes such as adultery, blasphemy, and sodomy were downgraded to political offenses, while judges lost the authority to reduce charges or negotiate outside the usual legal process. From this point forward, all offenses would be prosecuted as crimes against the state, even if no individual accuser was willing to bring the matter to court.[27]

As part of Joseph II’s civil law reforms, marriage was redefined as a civil contract. For non-Catholic couples, divorce became possible under certain conditions. The reforms also ensured equal inheritance rights for sons and daughters. Additionally, parents of children who refused to attend school could be fined. Joseph II’s reforms extended to education and society as well. Access to secondary schools and universities was made easier for citizens and peasants alike. In hiring teachers, only professional knowledge and competence were taken into account. Censorship was also relaxed during his reign.[28]

Education and medicine

To produce a literate citizenry, elementary education was made compulsory for all boys and girls, and higher education on practical lines was offered for a select few. Joseph created scholarships for talented poor students and allowed the establishment of schools for Jews and other religious minorities. In 1784 he ordered that the country change its language of instruction from Latin to German, a highly controversial step in a multilingual empire.

By the 18th century, centralization was the trend in medicine because more and better-educated doctors were requesting improved facilities. Cities lacked the budgets to fund local hospitals, and the monarchy wanted to end costly epidemics and quarantines. Joseph attempted to centralize medical care in Vienna through the construction of a single, large hospital, the famous Allgemeines Krankenhaus, which opened in 1784. Centralization worsened sanitation problems, causing epidemics and a 20% death rate in the new hospital; the city nevertheless became preeminent in the medical field in the next century.[29]

Religion

Joseph II’s church reforms, like his attempts to reshape the state, encountered widespread resistance throughout the Habsburg monarchy. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals, he pushed further than his mother Maria Theresa, implementing much more radical changes. One of his earliest acts was the “Edict of Toleration,” which granted Lutherans, Calvinists, and Greek Orthodox Christians the right to practice their faith openly. Though their churches faced restrictions—no bells, towers, or direct street access—the Protestant communities could now organize legally after centuries underground. The unexpectedly large number of converts to Protestantism led Joseph II to require a six-week Catholic “conversion course” before switching faiths. Despite opposition from many Catholics, this edict marked a significant step forward, granting non-Catholics civil rights equal to those of Catholics. Protestants could now hold public office, learn trades, and attend universities, removing religious affiliation as a barrier to civic participation.[30]

Joseph’s next major reform concerned the Jewish population, who had long faced discrimination. In 1782, he issued an edict allowing Jews to work in various professions, attend schools and universities, hire domestic staff, and rent city apartments—steps that undermined the old ghetto system. Discriminatory clothing laws were abolished. Joseph’s motives were both humanitarian and economic; he wished to make existing Jewish communities more useful to the state, not expand them. Despite resistance, he enforced these changes against entrenched prejudice.[30]

Joseph’s most consequential religious policy was the closure of monasteries that did not engage in education or healthcare, but focused solely on contemplation and prayer. While Maria Theresa had already begun some reforms, Joseph’s actions were broader, reflecting the era’s utilitarian belief that only those contributing to the common good were valuable. His goal was not hostility toward the Church, but practical reform: he wanted religious orders to play a greater role in social and educational work. Within a few years, about one third of Austrian and Hungarian monasteries were dissolved, and their assets redirected to a fund supporting religion and charity.[30]

His anticlerical and liberal innovations induced Pope Pius VI to pay him a visit in March 1782. Joseph received the Pope politely and showed himself a good Catholic, but refused to be influenced.[20] On the other hand, Joseph was very friendly to Freemasonry, as he found it highly compatible with his own Enlightenment philosophy, although he apparently never joined a Lodge himself. Freemasonry attracted many anticlericals and was condemned by the Church.

Joseph's feelings towards religion are reflected in a witticism he once spoke in Paris. While being given a tour of the Sorbonne's library, the archivist took Joseph to a dark room containing religious documents and lamented the lack of light which prevented Joseph from being able to read them. Joseph put the man at rest by saying "Ah, when it comes to theology, there is never much light."[31] Thus, Joseph was undoubtedly a much laxer Catholic than his mother. In 1789 he issued a charter of religious toleration for the Jews of Galicia, a region with a large Yiddish-speaking traditional Jewish population. The charter abolished communal autonomy whereby the Jews controlled their internal affairs; it promoted Germanization and the wearing of non-Jewish clothing.

Foreign policy

The Habsburg Empire also had a policy of war, expansion, colonization and trade as well as exporting intellectual influences. While opposing Prussia and Turkey, Austria maintained its defensive alliance with France and was friendly to Russia though trying to remove the Danubian Principalities from Russian influence. Mayer argues that Joseph was an excessively belligerent, expansionist leader, who sought to make the Habsburg monarchy the greatest of the European powers.[32] His main goal was to acquire Bavaria, if necessary in exchange for the Austrian Netherlands, but in 1778 and again in 1785 he was thwarted by King Frederick II of Prussia, whom he feared greatly; on the second occasion, a number of other German princes, wary of Joseph's designs on their lands, joined Frederick's side.[33] Russia acted in alliance with Austria and – at times – also with Prussian subsidies against Turkey, but after the Ottoman Empire had been largely weakened, Joseph II increasingly feared the growing influence of the Russian Empire in Southeast Europe. The emperor saw the Balkans, whose Slavic peoples were his subjects, as being in danger. He had to be concerned about security. He therefore traveled to Russia himself under the pseudonym Count Falkenstein to meet with Catherine II [34] that eventually led to the Austro-Russian Alliance (1781)[35]The agreement with Russia would later lead Austria into the expensive and largely futile Austro-Turkish War (1787–1791).[36]

The Balkan policy of both Maria Theresa and Joseph II reflected the Cameralism promoted by Prince Kaunitz, stressing consolidation of the borderlands by reorganization and expansion of the Military Frontier. Transylvania was incorporated into the frontier in 1761 and the frontier regiments became the backbone of the military order, with the regimental commander exercising military and civilian power. "Populationistik" was the prevailing theory of colonization, which measured prosperity in terms of labor. Joseph II also stressed economic development. Habsburg influence was an essential factor in Balkan development in the last half of the 18th century, especially for the Serbs and Croats.[37]

Reaction

Multiple interferences with old customs began to produce unrest in all parts of his dominions. Meanwhile, Joseph threw himself into a succession of foreign policies, all aimed at aggrandizement, and all equally calculated to offend his neighbors—all taken up with zeal, and dropped in discouragement. He endeavored to get rid of the Barrier Treaty, which debarred his Flemish subjects from the navigation of the Scheldt. When he was opposed by France, he turned to other schemes of alliance with the Russian Empire for the partition of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice. These plans also had to be given up in the face of the opposition of neighbors, and in particular of France. Then Joseph resumed his attempts to obtain Bavaria—this time by exchanging it for the Austrian Netherlands—and only provoked the formation of the Fürstenbund, organized by Frederick II of Prussia.[20]

Joseph II’s ambitious reforms provoked significant unrest and resistance within his diverse empire. While his centralized policies and Enlightenment-inspired changes were intended to modernize and unify the Habsburg lands, many local populations saw them as a threat to their traditions, privileges, and autonomy.In the Austrian Netherlands and Hungary everyone resented the way he tried to do away with all regional government, and to subordinate everything to his own personal rule in Vienna. The ordinary people were not happy. They loathed the Emperor's interference in every detail of their daily lives. [38]

In 1789, widespread unrest broke out, culminating in the so-called "Brabant Revolution." Rebels expelled imperial officials and briefly established the independent United Belgian States. Although the Habsburgs eventually regained control, the revolt revealed the deep dissatisfaction with Joseph’s methods. In Hungary, Joseph’s attempts to enforce German as the administrative language and to weaken the power of the Hungarian nobility were deeply unpopular. Hungarian nobles and clergy resisted efforts to centralize authority and erode their traditional privileges. Large-scale protests and passive resistance forced Joseph to withdraw many of his reforms in Hungary shortly before his death. The opposition demonstrated the limits of imperial power and the enduring strength of local identities.[38]

At the same time, Joseph II became entangled in conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. Hoping to gain territory and prestige, he entered into an alliance with Russia and declared war on the Ottomans in 1788. However, the campaign was poorly prepared and met with limited success.[39]

Remove ads

Death

In the autumn of 1788, the Emperor returned to Vienna already unwell. The medical treatment he underwent immediately afterwards was of little use. "I cough, I spit, and I have difficulty breathing," he wrote to his brother Leopold. 'I drink seltzer water and goat's milk, but I notice no improvement. This has been going on for eight months now.' It is now believed that the emperor suffered from exudative pulmonary tuberculosis. After months of relative wellbeing, his health deteriorated rapidly from January 1790 onwards. Constant fever, coughing fits, shortness of breath and chest pains tormented the monarch, who was shadowed by death. On the night of 19–20 February 1790, Joseph was able to sleep for a few hours, apparently thanks to painkillers. At five o'clock in the morning, he woke up and asked for his confessor. Five minutes later, he died. He was just under forty-nine years old. The Emperor was dressed in the uniform of a Field Marshal and, three days later, was buried in a plain copper coffin at the foot of his parents' magnificent Baroque coffins in the Kapuzinergruft in Vienna.[30][40]

Remove ads

Memory and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

The legacy of Josephinism would live on through the Austrian Enlightenment. To an extent, Joseph II's enlightenment beliefs were exaggerated by the author of what Beales called the "false Constantinople letters". Long considered genuine writings of Joseph II, these forged works have erroneously augmented the emperor's memory for centuries.[41][42]These legendary quotations have created a larger-than-life impression of Joseph II as a Voltaire and Diderot-like philosophe, more radical than he probably was.[43]

In 1849, the Hungarian Declaration of Independence declared that Joseph II was not a true King of Hungary as he was never crowned, thus any act from his reign was null and void.[44]

In 1888, Hungarian historian Henrik Marczali published a three-volume study of Joseph, the first important modern scholarly work on his reign, and the first to make systematic use of archival research. Marczali was Jewish and a product of the bourgeois-liberal school of historiography in Hungary, and he portrayed Joseph as a Liberal hero. The Russian scholar Pavel Pavlovich Mitrofanov published a thorough biography in 1907 that set the standard for a century after it was translated into German in 1910. The Mitrofanov interpretation was highly damaging to Joseph: he was not a populist emperor and his liberalism was a myth; Joseph was not inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment but by pure power politics. He was more of a despot than his mother. Dogmatism and impatience were the reasons for his failures.[45]

P. G. M. Dickson noted that Joseph II rode roughshod over age-old aristocratic privileges, liberties, and prejudices, thereby creating for himself many enemies, and they triumphed in the end. Joseph's attempt to reform the Hungarian lands illustrates the weakness of absolutism in the face of well-defended feudal liberties.[46] Behind his numerous reforms lay a comprehensive program influenced by the doctrines of enlightened absolutism, natural law, mercantilism, and physiocracy. With a goal of establishing a uniform legal framework to replace heterogeneous traditional structures, the reforms were guided at least implicitly by the principles of freedom and equality and were based on a conception of the state's central legislative authority. Joseph's accession marks a major break, since the preceding reforms under Maria Theresa had not challenged these structures; but there was no similar break at the end of the Josephinian era. The reforms initiated by Joseph II were continued to varying degrees under his successor Leopold and later successors, and given an absolute and comprehensive "Austrian" form in the Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (Austrian civil code) of 1811. They have been seen as providing a foundation for subsequent reforms extending into the 20th century, handled by much better politicians than Joseph II.[citation needed]

The Austrian-born American scholar Saul K. Padover reached a wide American public with his colorful The Revolutionary Emperor: Joseph II of Austria (1934). Padover celebrated Joseph's radicalism, saying his "war against feudal privileges" made him one of the great "liberators of humanity". Joseph's failures were attributed to his impatience and lack of tact, and his unnecessary military adventures; but despite all this, Padover claimed the emperor was the greatest of all Enlightenment monarchs.[47] While Padover depicted a sort of New Deal Democrat, Nazi historians in the 1930s made Joseph a precursor of Adolf Hitler.[48]

A new era of historiography began in the 1960s. American Paul Bernard rejected the German national, radical, and anticlerical images of Joseph and instead emphasized long-running continuities. He argued that Joseph's reforms were well suited to the needs of the day. Many failed because of economic backwardness and Joseph's unfortunate foreign policy.[49] British historian Tim Blanning stressed profound contradictions inherent in his policies that made them a failure. For example, Joseph encouraged small-scale peasant holdings, thus retarding economic modernization that only the large estates could handle.[50] French historian Jean Bérenger concludes that despite his many setbacks, Joseph's reign "represented a decisive phase in the process of the modernization of the Austrian Monarchy". The failures came because he "simply wanted to do too much, too fast".[51] Szabo concludes that by far the most important scholarship on Joseph is by Derek Beales, appearing over three decades and based on exhaustive searches in many archives. Beales looks at the emperor's personality, with its arbitrary behavior and mixture of affability and irascibility. Beales shows that Joseph genuinely appreciated Mozart's music and greatly admired his operas. Like most other scholars, Beales has a negative view of Joseph's foreign policies. Beales finds that Joseph was despotic in the sense of transgressing established constitutions and rejecting sound advice, but not despotic in the sense of any gross abuse of power.[52]

Popular memory

Joseph's image in popular memory has been varied. After his death the central government built many monuments to him across his lands. On independence in 1918, the first Czechoslovak Republic tore down the monuments. While the Czechs credited Joseph II with educational reforms, religious toleration, and the easing of censorship, they condemned his policies of centralization and Germanization that they blamed for causing a decline in Czech culture.[53]

Patron of the arts

Like many of the "enlightened despots" of his time, Joseph was a lover and patron of the arts and is remembered as such. He was known as the "Musical King" and steered Austrian high culture towards a more Germanic orientation. He commissioned the German-language opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail from Mozart. The young Ludwig van Beethoven was commissioned to write a funeral cantata for him, but it was not performed because of its technical difficulty.

Joseph is prominently featured in Peter Shaffer's play Amadeus and the movie based upon it. In the film version, he is portrayed by actor Jeffrey Jones as a well-meaning but somewhat befuddled monarch of limited but enthusiastic musical skill, easily manipulated by Antonio Salieri; however, Shaffer has made it clear his play is fiction in many respects and not intended to portray historical reality. Joseph was portrayed by Danny Huston in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette.

His reign saw the flourishing of Viennese classical music and the development of public concerts and performances, moving the arts beyond the exclusive domain of the aristocracy. Joseph II’s policies fostered a vibrant cultural scene in Vienna, helping the city become one of Europe’s leading centers of music, theatre, and intellectual life during the late 18th century. A series of measures taken by Emperor Joseph II demonstrate his concern for the people. In 1766, for example, he opened the Prater to the Viennese population, and innkeepers and coffeehouse owners subsequently settled there. From 1774 onwards, the gate that had blocked the entrance to this former Habsburg hunting ground at night was removed, making the Prater accessible even after dark. In a similar vein, Joseph II also opened the imperial Augarten park to the public. At the entrance to this area, there is an inscription that is very indicative of his intentions: “A place of enjoyment dedicated to all people by your admirer.”[54]

Remove ads

Coat of arms

Middle Coat of arms |

Greater Coat of arms |

Greater Coat of arms (Shield variant) |

Greater Coat of arms (Shield variant with supporters) |

Titles

The full titulature of Joseph after he inherited the thrones of the Holy Roman Empire and the vast realms of Central and Eastern Europe from his mother Maria Theresa was as follows:

"His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty, Joseph II, by the Grace of God elected Holy Roman Emperor, forever Augustus, King of Germany, King of Hungary, of Bohemia, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, of Slavonia, of Galicia, of Lodomeria, of Italy, of Cumania, of Bulgaria, of Serbia, etc. etc.; Archduke of Austria; Duke of Burgundy, of Styria, of Carinthia and of Carniola; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Brabant, of Limburg, of Luxemburg, of Guelders, of Württemberg, of Upper and Lower Silesia, of Milan, of Mantua, of Parma, of Piacenza, of Guastalla, of Auschwitz, of Zator and of Teck; Prince of Swabia; Princely Count of Habsburg, of Flanders, of Tyrol, of Hainault, of Kyburg, of Gorizia and of Gradisca; Margrave of Burgau, of Upper and Lower Lusatia; Count of Namur; Lord of the Wendish Mark and of Mechlin; Duke of Lorraine and Bar, Grand Duke of Tuscany, etc. etc. [55]

Remove ads

Ancestry

See also

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads