Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Jud Süß (Feuchtwanger novel)

1925 historical novel by Lion Feuchtwanger From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

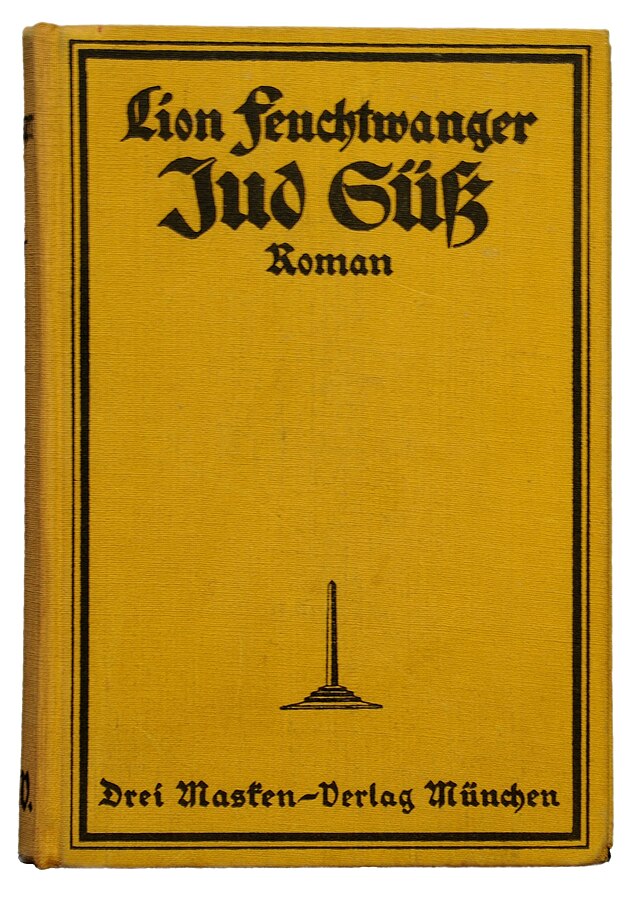

Jud Süß is a 1925 historical novel by Lion Feuchtwanger based on the life of Joseph Süß Oppenheimer.[1]

Historical background

Joseph Süß Oppenheimer was an 18th-century court Jew in the employ of Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg in Stuttgart. In the course of his work for the duke, Oppenheimer made a number of powerful enemies, some of whom conspired to bring about his arrest and execution after Karl Alexander's death.

The story was the subject of a number of literary and dramatic treatments over the course of more than a century, the earliest of these being Wilhelm Hauff's 1827 novella. The most successful literary adaptation was Feuchtwanger's novel, which is based on a play that he wrote in 1916 but subsequently withdrew. The novel was translated into English by Willa and Edwin Muir. In the afterword to his novel, Feuchtwanger characterized Hauff's novella as 'naïvely anti-Semitic'.[2]

Remove ads

Feuchtwanger's themes

For Feuchtwanger, Süß was a forerunner that symbolized the evolution in European philosophy and cultural mentality, representing a shift towards Eastern philosophy, from Nietzsche to Buddha, from "the old to the new covenant."[3] Karl Leydecker writes:

For Feuchtwanger, Jud Süß was primarily a novel of ideas, dealing with a number of philosophical oppositions such as vita activa versus vita contemplativa, outer versus inner life, appearance versus essence, power versus wisdom, the pursuit of one's desires vs. the denial of desires, Nietzsche vs. Buddha.[4]

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

The novel tells the story of a Jewish businessman, Joseph Süß Oppenheimer, who, because of his exceptional talent for finance and politics, becomes the top advisor for the Duke of Württemberg. Surrounded by jealous and hateful enemies, Süß helps the Duke create a corrupt state that brings the two of them immense wealth and power.

Süß discovers he is the illegitimate son of a respected nobleman, but decides to continue living as a Jew, as he is proud of having achieved such a position despite this. The Duke discovers that Süß has a daughter who he has been hiding; the Duke tries to rape her and accidentally kills her. Süß is devastated. He takes revenge by first encouraging the Duke's plan to overthrow the Parliament and then exposing it; the Duke dies in fury. Subsequently, Süß realizes nothing will bring back his daughter, and apathetically turns himself over to authorities. Accused of fraud, embezzlement, treason, lecherous relations with the court ladies and accepting bribes, his case is adjudicated. Under pressure from the public, the court sentences him to death by hanging. Despite being given a last chance for reprieve if he reveals his noble origins or converts to Christianity, he dies reciting the Shema Yisrael, the most important prayer in Judaism.

Adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

Ashley Dukes and Paul Kornfeld each wrote dramatic adaptations of the Feuchtwanger novel. Orson Welles made his stage debut (at the Gate Theatre on October 13, 1931) in Dukes's adaptation, as the Duke. In 1934, Lothar Mendes directed a film adaptation of the novel starring Conrad Veidt.[5]: 42–44

In Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbels had Veit Harlan direct a virulently anti-Semitic film to counter the philo-semitism of Feuchtwanger's novel and Mendes's adaption of it. Harlan's film violated almost everything about the novel's characters and its sentiments. In the Harlan film, Süß rapes a Gentile German girl and tortures her father and fiancé before being put to death for his crimes.

In Feuchtwanger's play and novel, Josef Süß Oppenheimer emerges as a father, and his fictional daughter (named Tamar in the play, Naemi in the novel) provides both a central ideal and a turning point for the narrative. In Harlan's Nazi film, the central female figure Dorothea Sturm (played by Kristina Söderbaum) is, again, represented as ideal. However, Harlan's version of her violation and subsequent suicide transform Süß's execution (historically a miscarriage of justice) into a symbol of the judicial court's righteousness that is hailed by the masses. Like a negative image, Harlan's film inverts Feuchtwanger's narrative, reversing the central elements; Feuchtwanger's depiction of Oppenheimer's journey from power-hungry financial and political genius to a more enlightened human being is turned into an anti-Semitic propaganda piece.[6]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads