Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

New Testament

Second division of the Christian biblical canon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The New Testament[a] (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events relating to first-century Christianity. The New Testament's background, the first division of the Christian Bible, has the name of Old Testament, which is based primarily upon the Hebrew Bible; together they are regarded as Sacred Scripture by Christians.[1]

The New Testament is a collection of 27 Christian texts written in Koine Greek by various authors, forming the second major division of the Christian Bible. It includes four gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, epistles attributed to Paul and other authors, and the Book of Revelation. The New Testament canon developed gradually over the first few centuries of Christianity through a complex process of debate, rejection of heretical texts, and recognition of writings deemed apostolic, culminating in the formalization of the 27-book canon by the late 4th century. It has been widely accepted across Christian traditions since Late Antiquity.[2]

Literary analysis suggests many of its texts were written in the mid-to-late first century. There is no scholarly consensus on the date of composition of the latest New Testament text. The earliest surviving New Testament manuscripts date from the late second to early third centuries AD, with the possible exception of Papyrus 52.

The New Testament was transmitted through thousands of manuscripts in various languages and church quotations and contains variants. Textual criticism uses surviving manuscripts to reconstruct the oldest version feasible and to chart the history of the written tradition.[3] It has varied reception among Christians today. It is viewed as a holy scripture alongside Sacred Tradition among Catholics[4] and Orthodox, while evangelicals and some other Protestants view it as the inspired word of God without tradition.[5]

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

The word testament

The word testament in the expression "New Testament" refers to a Christian new covenant that Christians believe completes or fulfils the Mosaic covenant (the Jewish covenant) that Yahweh (the God of Israel) made with the people of Israel on Mount Sinai through Moses, described in the books of the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[6] While Christianity traditionally even claims this Christian new covenant as being prophesied in the Jewish Bible's Book of Jeremiah,[7] Judaism traditionally disagrees:[8][9]

Behold, the days come, saith the LORD, that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel, and with the house of Judah; not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt; forasmuch as they broke My covenant, although I was a lord over them, saith the LORD. But this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, saith the LORD, I will put My law in their inward parts, and in their heart will I write it; and I will be their God, and they shall be My people; and they shall teach no more every man his neighbour, and every man his brother, saying: 'Know the LORD'; for they shall all know Me, from the least of them unto the greatest of them, saith the LORD; for I will forgive their iniquity, and their sin will I remember no more.

The word covenant means 'agreement' (from Latin con-venio "to agree", literally 'to come together'): the use of the word testament, which describes the different idea of written instructions for inheritance after death, to refer to the covenant with Israel in the Old Testament, is foreign to the original Hebrew word brit (בְּרִית) describing it, which only means 'alliance, covenant, pact' and never 'inheritance instructions after death'.[10][11] This use comes from the transcription of Latin testamentum 'will (left after death)',[12] a literal translation of Greek diatheke (διαθήκη) 'will (left after death)',[13] which is the word used to translate Hebrew brit in the Septuagint.[14]

The choice of this word diatheke, by the Jewish translators of the Septuagint in Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd century BC, has been understood in Christian theology to imply a reinterpreted view of the Old Testament covenant with Israel as possessing characteristics of a 'will left after death' (the death of Jesus) and has generated considerable attention from biblical scholars and theologians:[15] in contrast to the Jewish usage where brit was the usual Hebrew word used to refer to pacts, alliances and covenants in general, like a common pact between two individuals,[b] and to the one between God and Israel in particular,[c] in the Greek world diatheke was virtually never used to refer to an alliance or covenant (one exception is noted in a passage from Aristophanes)[6] and referred instead to a will left after the death of a person. There is scholarly debate[16][15] as to the reason why the translators of the Septuagint chose the term diatheke to translate Hebrew brit, instead of another Greek word generally used to refer to an alliance or covenant.

The phrase New Testament as the collection of scriptures

The use of the phrase New Testament (Koine Greek: Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, Hē Kainḕ Diathḗkē) to describe a collection of first- and second-century Christian Greek scriptures can be traced back to Tertullian in his work Against Praxeas.[17][18][19] Irenaeus uses the phrase New Testament several times, but does not use it in reference to any written text.[18] In Against Marcion, written c. 208 AD, Tertullian writes of:[20]

the Divine Word, who is doubly edged with the two testaments of the law and the gospel.

And Tertullian continues later in the book, writing:[21][d]

it is certain that the whole aim at which he [Marcion] has strenuously laboured, even in the drawing up of his Antitheses, centres in this, that he may establish a diversity between the Old and the New Testaments, so that his own Christ may be separate from the Creator, as belonging to this rival God, and as alien from the law and the prophets.

By the 4th century, the existence—even if not the exact contents—of both an Old and New Testament had been established. Lactantius, a 3rd–4th century Christian author wrote in his early-4th-century Latin Institutiones Divinae (Divine Institutes):[22]

But all scripture is divided into two Testaments. That which preceded the advent and passion of Christ—that is, the law and the prophets—is called the Old; but those things which were written after His resurrection are named the New Testament. The Jews make use of the Old, we of the New: but yet they are not discordant, for the New is the fulfilling of the Old, and in both there is the same testator, even Christ, who, having suffered death for us, made us heirs of His everlasting kingdom, the people of the Jews being deprived and disinherited. As the prophet Jeremiah testifies when he speaks such things: "Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will make a new testament to the house of Israel and the house of Judah, not according to the testament which I made to their fathers, in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt; for they continued not in my testament, and I disregarded them, saith the Lord."[23] ... For that which He said above, that He would make a new testament to the house of Judah, shows that the old testament which was given by Moses was not perfect; but that which was to be given by Christ would be complete.

Eusebius describes the collection of Christian writings as "covenanted" (ἐνδιαθήκη) books in Hist. Eccl. 3.3.1–7; 3.25.3; 5.8.1; 6.25.1.

Remove ads

Books

Summarize

Perspective

The Gospels

Each of the four gospels in the New Testament narrates the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth (the gospel of Mark in the original text ends with the empty tomb and has no account of the post-resurrection appearances, but the emptiness of the tomb implies a resurrection). The word "gospel" derives from the Old English gōd-spell[24] (rarely godspel), meaning "good news" or "glad tidings". Its Hebrew equivalent being "besorah" (בְּשׂוֹרָה). The gospel was considered the "good news" of the coming Kingdom of Messiah, and the redemption through the life and death of Jesus, the central Christian message.[25]

Starting in the late second century, the four narrative accounts of the life and work of Jesus Christ have been referred to as "The Gospel of ..." or "The Gospel according to ..." followed by the name of the supposed author. The first author to explicitly name the canonical gospels is Irenaeus of Lyon,[18][26] who promoted the four canonical gospels in his book Against Heresies, written around 180.[27]

- The Gospel of Matthew, ascribed to the Apostle Matthew. This gospel begins with a genealogy of Jesus and a story of his birth that includes a visit from magi and a flight into Egypt, and it ends with the commissioning of the disciples by the resurrected Jesus.[28]

- The Gospel of Mark, ascribed to Mark the Evangelist. This gospel begins with the preaching of John the Baptist and the baptism of Jesus and ends with the Ascension of Jesus.[29]

- The Gospel of Luke, ascribed to Luke the Evangelist, who was not one of the Twelve Apostles, but was mentioned as a companion of the Apostle Paul and as a physician.[30]

- The Gospel of John, ascribed to John the Evangelist.[31] This gospel begins with a philosophical prologue and ends with appearances of the resurrected Jesus.[31]

These four gospels that were eventually included in the New Testament were only a few among many other early Christian gospels. The existence of such texts is even mentioned at the beginning of the Gospel of Luke.[32] Many non-canonical gospels were also written, all later than the four canonical gospels, and like them advocating the particular theological views of their various authors.[33][34] In modern scholarship, the Synoptic Gospels are the primary sources for reconstructing Christ's ministry.[35][note 1]

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles is a narrative of the apostles' ministry and activity after Christ's death and resurrection, from which point it resumes and functions as a sequel to the Gospel of Luke. Examining style, phraseology, and other evidence, modern scholarship generally concludes that Acts and the Gospel of Luke share the same author, referred to as Luke–Acts. Luke–Acts does not name its author.[36] Church tradition identified him as Luke the Evangelist, the companion of Paul, but the majority of scholars reject this due to the many differences between Acts and the authentic Pauline letters, though most scholars still believe the author, whether named Luke or not, met Paul.[37][38][39][40][41] The most probable date of composition is around 80–90 AD, although some scholars date it significantly later,[42][43] and there is evidence that it was still being substantially revised well into the 2nd century.[44]

Epistles

Pauline letters to churches

The Pauline letters are the thirteen New Testament books that present Paul the Apostle as their author.[e] Paul's authorship of six of the letters is disputed. Four are thought by most modern scholars to be pseudepigraphic, i.e., not actually written by Paul even if attributed to him within the letters themselves. Opinion is more divided on the other two disputed letters (2 Thessalonians and Colossians).[48] These letters were written to Christian communities in specific cities or geographical regions, often to address issues faced by that particular community. Prominent themes include the relationship both to broader "pagan" society, to Judaism, and to other Christians.[49]

- Epistle to the Romans

- First Epistle to the Corinthians

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- Epistle to the Galatians

- Epistle to the Ephesians*

- Epistle to the Philippians

- Epistle to the Colossians*

- First Epistle to the Thessalonians

- Second Epistle to the Thessalonians*

[Disputed letters are marked with an asterisk (*).]

Pauline letters to persons

The last four Pauline letters in the New Testament are addressed to individual persons. They include the following:

[Disputed letters are marked with an asterisk (*).]

All of the above except for Philemon are known as the pastoral epistles. They are addressed to individuals charged with pastoral oversight of churches and discuss issues of Christian living, doctrine and leadership. They often address different concerns to those of the preceding epistles. These letters are believed by many to be pseudepigraphic. Some scholars (e.g., Bill Mounce, Ben Witherington, R.C. Sproul) will argue that the letters are genuinely Pauline, or at least written under Paul's supervision.

Hebrews

The Epistle to the Hebrews addresses a Jewish audience who had come to believe that Jesus was the Anointed One (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ—transliterated in English as "Moshiach", or "Messiah"; Greek: Χριστός—transliterated in English as "Christos", for "Christ") who was predicted in the writings of the Hebrew Scriptures. The author discusses the superiority of the new covenant and the ministry of Jesus, to the Mosaic Law Covenant[50] and urges the readers in the practical implications of this conviction through the end of the epistle.[51]

The book has been widely accepted by the Christian church as inspired by God and thus authoritative, despite the acknowledgment of uncertainties about who its human author was. Regarding authorship, although the Epistle to the Hebrews does not internally claim to have been written by the Apostle Paul, some similarities in wordings to some of the Pauline Epistles have been noted and inferred. In antiquity, some began to ascribe it to Paul in an attempt to provide the anonymous work an explicit apostolic pedigree.[52]

In the 4th century, Jerome and Augustine of Hippo supported Paul's authorship. The Church largely agreed to include Hebrews as the fourteenth letter of Paul, and affirmed this authorship until the Reformation. The letter to the Hebrews had difficulty in being accepted as part of the Christian canon because of its anonymity.[53] As early as the 3rd century, Origen wrote of the letter, "Men of old have handed it down as Paul's, but who wrote the Epistle God only knows."[54]

Contemporary scholars often reject Pauline authorship for the epistle to the Hebrews,[55] based on its distinctive style and theology, which are considered to set it apart from Paul's writings.[56]

Catholic epistles

- Second Epistle of Peter, ascribed to the Apostle Peter, though widely considered not to have been written by him.[57]

Book of Revelation

The final book of the New Testament is the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse of John. In the New Testament canon, it is considered prophetical or apocalyptic literature. Its authorship has been attributed either to John the Apostle (in which case it is often thought that John the Apostle is John the Evangelist, i.e. author of the Gospel of John) or to another John designated "John of Patmos" after the island where the text says the revelation was received (1:9). Some ascribe the writership date as c. 81–96 AD, and others at around 68 AD.[58] The work opens with letters to seven local congregations of Asia Minor and thereafter takes the form of an apocalypse, a "revealing" of divine prophecy and mysteries, a literary genre popular in ancient Judaism and Christianity.[59]

New Testament canons

- Table notes

- The growth and development of the Armenian biblical canon is complex; extra-canonical New Testament books appear in historical canon lists and recensions that are either distinct to this tradition, or where they do exist elsewhere, never achieved the same status.[citation needed] Some of the books are not listed in this table; these include the Prayer of Euthalius, the Repose of St. John the Evangelist, the Doctrine of Addai, a reading from the Gospel of James, the Second Apostolic Canons, the Words of Justus, Dionysius Areopagite, the Preaching of Peter, and a Poem by Ghazar.[citation needed] (Various sources[citation needed] also mention undefined Armenian canonical additions to the Gospels of Mark and John. These may refer to the general additions—Mark 16:9–20 and John 7:53–8:11—discussed elsewhere in these notes.) A possible exception here to canonical exclusivity is the Second Apostolic Canons, which share a common source—the Apostolic Constitutions—with certain parts of the Orthodox Tewahedo New Testament broader canon.[citation needed] The Acts of Thaddeus was included in the biblical canon of Gregory of Tatev.[60] There is some uncertainty about whether Armenian canon lists include the Doctrine of Addai or the related Acts of Thaddeus.[citation needed] Moreover, the correspondence between King Abgar V and Jesus Christ, which is found in various forms—including within both the Doctrine of Addai and the Acts of Thaddeus—sometimes appears separately (see list[full citation needed]). The Prayer of Euthalius and the Repose of St. John the Evangelist appear in the appendix of the 1805 Armenian Zohrab Bible.[citation needed] Some of the aforementioned books, though they are found within canon lists, have nonetheless never been discovered to be part of any Armenian biblical manuscript.[60]

- Though widely regarded as non-canonical,[citation needed] the Gospel of James obtained early liturgical acceptance among some Eastern churches and remains a major source for many of Christendom's traditions related to Mary, the mother of Jesus.[citation needed]

- The Diatessaron, Tatian's gospel harmony, became a standard text in some Syriac-speaking churches down to the 5th century, when it gave way to the four separate gospels found in the Peshitta.[citation needed]

- Parts of these four books are not found in the most reliable ancient sources; in some cases, are thought to be later additions, and have therefore not appeared historically in every biblical tradition.[citation needed] They are as follows: Mark 16:9–20, John 7:53–8:11, the Comma Johanneum, and portions of the Western version of Acts. To varying degrees, arguments for the authenticity of these passages—especially for the one from the Gospel of John—have occasionally been made.[citation needed]

- Skeireins, a commentary on the Gospel of John in the Gothic language, was included in the Wulfila Bible.[citation needed] It exists today only in fragments.[citation needed]

- The Acts of Paul and Thecla and the Third Epistle to the Corinthians are all portions of the greater Acts of Paul narrative, which is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus, but has survived only in fragments.[citation needed] Some of the content within these individual sections may have developed separately.[citation needed]

- These four works were questioned or "spoken against" by Martin Luther, and he changed the order of his New Testament to reflect this, but he did not leave them out, nor has any Lutheran body since.[citation needed] Traditional German Luther Bibles are still printed with the New Testament in this changed "Lutheran" order.[citation needed] The vast majority of Protestants embrace these four works as fully canonical.[citation needed]

- The Peshitta excludes 2 John, 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation, but certain Bibles of the modern Syriac traditions include later translations of those books.[citation needed] Still today, the official lectionary followed by the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Assyrian Church of the East presents lessons from only the twenty-two books of Peshitta, the version to which appeal is made for the settlement of doctrinal questions.[citation needed]

- The Epistle to the Laodiceans is present in some western non-Roman Catholic translations and traditions.[citation needed] Especially of note is John Wycliffe's inclusion of the epistle in his English translation,[citation needed] and the Quakers' use of it to the point where they produced a translation and made pleas for its canonicity, see Poole's Annotations, on Col. 4:16. The epistle is nonetheless widely rejected by the vast majority of Protestants.[citation needed]

- The Apocalypse of Peter, though not listed in this table, is mentioned in the Muratorian fragment and is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus.[citation needed] It was also held in high regard by Clement of Alexandria.[citation needed]

- Other known writings of the Apostolic Fathers not listed in this table are as follows: the seven Epistles of Ignatius, the Epistle of Polycarp, the Martyrdom of Polycarp, the Epistle to Diognetus, the fragment of Quadratus of Athens, the fragments of Papias of Hierapolis, the Reliques of the Elders Preserved in Irenaeus, and the Apostles' Creed.[citation needed]

- Though they are not listed in this table, the Apostolic Constitutions were considered canonical by some including Alexius Aristenus, John of Salisbury, and to a lesser extent, Grigor Tat`evatsi.[citation needed] They are even classified as part of the New Testament canon within the body of the Constitutions itself; moreover, they are the source for a great deal of the content in the Orthodox Tewahedo broader canon.[citation needed]

- These five writings attributed to the Apostolic Fathers are not currently considered canonical in any biblical tradition, though they are more highly regarded by some more than others.[citation needed] Nonetheless, their early authorship and inclusion in ancient biblical codices, as well as their acceptance to varying degrees by various early authorities, requires them to be treated as foundational literature for Christianity as a whole.[according to whom?][citation needed]

- Ethiopic Clement and the Ethiopic Didascalia are distinct from and should not be confused with other ecclesiastical documents known in the west by similar names.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Book order

The order in which the books of the New Testament appear differs between some collections and ecclesiastical traditions. In the Latin West, prior to the Vulgate (an early 5th-century Latin version of the Bible), the four Gospels were arranged in the following order: Matthew, John, Luke, and Mark.[f] The Syriac Peshitta places the major Catholic epistles (James, 1 Peter, and 1 John) immediately after Acts and before the Pauline epistles.

The order of an early edition of the letters of Paul is based on the size of the letters: longest to shortest, though keeping 1 and 2 Corinthians and 1 and 2 Thessalonians together. The Pastoral epistles were apparently not part of the Corpus Paulinum in which this order originated and were later inserted after 2 Thessalonians and before Philemon. Hebrews was variously incorporated into the Corpus Paulinum either after 2 Thessalonians, after Philemon (i.e. at the very end), or after Romans.

Luther's canon, found in the 16th-century Luther Bible, continues to place Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Apocalypse (Revelation) last. This reflects the thoughts of the Reformer Martin Luther on the canonicity of these books.[64][g][65]

Authors

Summarize

Perspective

It is considered the books of the New Testament were all or nearly all written by Jewish Christians—that is, Jewish disciples of Christ, who lived in the Roman Empire, and under Roman occupation.[66] The author of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts is frequently thought of as an exception; scholars are divided as to whether he was a Gentile or a Hellenistic Jew.[67] A few scholars identify the author of the Gospel of Mark as probably a Gentile, and similarly for the Gospel of Matthew, though most assert Jewish-Christian authorship.[68][69][70][verification needed]

However, more recently the above understanding has been challenged by the publication of evidence showing only educated elites after the Jewish War would have been capable of producing the prose found in the Gospels.[71][verification needed][page needed]

Gospels

Authorship of the Gospels remains divided among both evangelical and critical scholars. The names of each Gospel stems from church tradition, and yet the authors of the Gospels do not identify themselves in their respective texts. All four gospels and the Acts of the Apostles are anonymous works.[72] The Gospel of John claims to be based on eyewitness testimony from the Disciple whom Jesus loved, but never names this character. The author of Luke-Acts claimed to access an eyewitness to Paul; this claim remains accepted by most scholars.[h] Objections to this viewpoint mainly take the form of the following two interpretations, but also include the claim that Luke-Acts contains differences in theology and historical narrative which are irreconcilable with the authentic letters of Paul the Apostle.[74] According to Bart D. Ehrman of the University of North Carolina, none of the authors of the Gospels were eyewitnesses or even explicitly claimed to be eyewitnesses of Jesus's life.[75][76][77] Ehrman has argued for a scholarly consensus that many New Testament books were not written by the individuals whose names are attached to them.[78][79] Scholarly opinion is that names were fixed to the gospels by the mid second century AD.[80] Many scholars believe that none of the gospels were written in the region of Palestine.[81]

Christian tradition identifies John the Apostle with John the Evangelist, the supposed author of the Gospel of John. Traditionalists tend to support the idea that the writer of the Gospel of John himself claimed to be an eyewitness in their commentaries of John 21:24 and therefore the gospel was written by an eyewitness.[82][83] This idea is rejected by the majority of modern scholars; most think the verses claim the beloved disciple was the author of the gospel,[84] but the passage is widely viewed as a later addition by either the author of chapters 1-20 or by another redactor,[85] though a growing minority view it as part of the earliest text.[86][87][88] The author may also claim to be a witness in 19:35.[89][90]

Most scholars hold to the two-source hypothesis, which posits that the Gospel of Mark was the first gospel to be written, though alternative hypotheses that posit the direct use of Matthew by Luke or vice versa without Q are increasing in popularity within scholarship.[91][92] On this view, the authors of the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke used as sources the Gospel of Mark and a hypothetical Q document to write their individual gospel accounts.[93][94][95][96][97] These three gospels are called the Synoptic Gospels, because they include many of the same stories, often in the same sequence, and sometimes in exactly the same wording. Scholars agree that the Gospel of John was written last, by using a different tradition and body of testimony. In addition, most scholars agree that the author of Luke also wrote the Acts of the Apostles. Scholars hold that these books constituted two-halves of a single work, Luke–Acts.[citation needed]

Acts

The same author appears to have written the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, and most refer to them as the Lucan texts.[98][99] The most direct evidence comes from the prefaces of each book; both were addressed to Theophilus, and the preface to the Acts of the Apostles references "my former book" about the ministry of Jesus.[100] Furthermore, there are linguistic and theological similarities between the two works, suggesting that they have a common author.[101][102][103][104]

Pauline epistles

The Pauline epistles are the thirteen books in the New Testament traditionally attributed to Paul of Tarsus. Seven letters are generally classified as "undisputed", expressing contemporary scholarly near consensus that they are the work of Paul: Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon. Six additional letters bearing Paul's name do not currently enjoy the same academic consensus: Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy and Titus.[i]

The anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews is, despite unlikely Pauline authorship, often functionally grouped with these thirteen to form a corpus of fourteen "Pauline" epistles.[j]

While many scholars uphold the traditional view, some question whether the first three, called the "Deutero-Pauline Epistles", are authentic letters of Paul. As for the latter three, the "Pastoral epistles", some scholars uphold the traditional view of these as the genuine writings of the Apostle Paul;[i] most regard them as pseudepigrapha.[107]

One might refer to the Epistle to the Laodiceans and the Third Epistle to the Corinthians as examples of works identified as pseudonymous. Since the early centuries of the church, there has been debate concerning the authorship of the anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews, and contemporary scholars generally reject Pauline authorship.[108]

The epistles all share common themes, emphasis, vocabulary and style; they exhibit a uniformity of doctrine concerning the Mosaic Law, Jesus, faith, and various other issues. All of these letters easily fit into the chronology of Paul's journeys depicted in Acts of the Apostles.

Other epistles

The author of the Epistle of James identifies himself in the opening verse as "James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ". From the middle of the 3rd century, patristic authors cited the Epistle as written by James the Just.[109] Ancient and modern scholars have always been divided on the issue of authorship. Many consider the epistle to be written in the late 1st or early 2nd centuries.[110]

The author of the First Epistle of Peter identifies himself in the opening verse as "Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ", and the view that the epistle was written by St. Peter is attested to by a number of Church Fathers: Irenaeus (140–203), Tertullian (150–222), Clement of Alexandria (155–215) and Origen of Alexandria (185–253). Unlike The Second Epistle of Peter, the authorship of which was debated in antiquity, there was little debate about Peter's authorship of this first epistle until the 18th century. Although 2 Peter internally purports to be a work of the apostle, many biblical scholars have concluded that Peter is not the author.[111] For an early date and (usually) for a defense of the Apostle Peter's authorship see Kruger,[112] Zahn,[113] Spitta,[114][full citation needed] Bigg,[115] and Green.[116]

The Epistle of Jude title is written as follows: "Jude, a servant of Jesus Christ and brother of James".[117] The debate has continued over the author's identity as the apostle, the brother of Jesus, both, or neither.[118]

Johannine works

The Gospel of John, the three Johannine epistles, and the Book of Revelation, exhibit marked similarities, although more so between the gospel and the epistles (especially the gospel and 1 John) than between those and Revelation.[119] Most scholars therefore treat the five as a single corpus of Johannine literature, albeit not from the same author.[120]

Burkett argues the gospel went through two or three "editions" before reaching its current form around AD 90–110, though more recent scholars tend to be less interested in theories about hypothetical editions or sources of the gospel.[121][122][88] It speaks of an unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved" as the source of its traditions, but according to Burkett does not say specifically that he is its author except in John 21, which is widely viewed as a later addition by either the author of chapters 1-20 or by another redactor,[85] though Keith notes a growing minority views it as original.[123][88] According to Méndez, the gospel gradually identifies its narrator as the beloved disciple, notably in chapter 19.[90] Christian tradition identifies this disciple as the apostle John, but while this idea still has supporters, for a variety of reasons the majority of modern scholars have abandoned it or hold it only tenuously.[124] It is significantly different from the synoptic gospels, with major variations in material, theological emphasis, chronology, and literary style, sometimes amounting to contradictions.[125]

The author of the Book of Revelation identifies himself several times as "John".[126] and states that he was on Patmos when he received his first vision.[127] As a result, the author is sometimes referred to as John of Patmos. The author has traditionally been identified with John the Apostle to whom the Gospel and the epistles of John were attributed. It was believed that he was exiled to the island of Patmos during the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian, and there wrote Revelation. Justin Martyr (c. 100–165 AD) who was acquainted with Polycarp, who had been mentored by John, makes a possible allusion to this book, and credits John as the source.[128] Irenaeus (c. 115–202) assumes it as a conceded point. According to the Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible, modern scholars are divided between the apostolic view and several alternative hypotheses put forth in the last hundred years or so.[129] Ben Witherington points out that linguistic evidence makes it unlikely that the books were written by the same person.[130]

Remove ads

Dating the New Testament

Summarize

Perspective

There is no scholarly consensus on the date of composition of the latest New Testament texts. John A. T. Robinson, Dan Wallace, William F. Albright, Maurice Casey, and James Crossley all dated many or all of the books of the New Testament before 70 AD.[131][132][133] Jonathan Bernier's recent argument for early dates has enjoyed a positive reception, with endorsements from Chris Keith and Anders Runesson, among others.[134] Many other scholars, such as Bart D. Ehrman and Stephen L. Harris, date some New Testament texts much later than this;[135][136][137] Richard Pervo dated Luke–Acts to c. 115 AD,[42] and David Trobisch places Acts in the mid-to-late second century, contemporaneous with the publication of the first New Testament canon.[43] Whether the Gospels were composed before or after 70 AD, according to Bas van Os, the lifetime of various eyewitnesses that includes Jesus's own family through the end of the First Century is very likely statistically.[138] Markus Bockmuehl finds this structure of lifetime memory in various early Christian traditions.[139]

External evidence

The earliest manuscripts of New Testament books date from the late second to early third centuries (although see Papyrus 52 for a possible exception).[140]

Internal evidence

Literary analysis of the New Testament texts themselves can be used to date many of the books of the New Testament to the mid-to-late first century. The earliest works of the New Testament are the letters of the Apostle Paul. It can be determined that 1 Thessalonians is likely the earliest of these letters, written around 52 AD.[141]

Remove ads

Language

Summarize

Perspective

The major languages spoken by both Jews and Greeks in the Holy Land at the time of Jesus were Aramaic and Koine Greek, and also a colloquial dialect of Mishnaic Hebrew. It is generally agreed by most scholars that the historical Jesus primarily spoke Aramaic,[142] perhaps also some Hebrew and Koine Greek. The majority view is that all of the books that would eventually form the New Testament were written in the Koine Greek language.[3][143]

As Christianity spread, these books were later translated into other languages, most notably, Latin, Syriac, and Egyptian Coptic. Some of the Church Fathers[144] imply or claim that Matthew was originally written in Hebrew or Aramaic, and then soon after was written in Koine Greek. Nevertheless, some scholars believe the Gospel of Matthew known today was composed in Greek and is neither directly dependent upon nor a translation of a text in a Semitic language.[145]

Style

The style of Koine Greek in which the New Testament is written differs from the general Koine Greek used by Greek writers of the same era, a difference that some scholars have explained by the fact that the authors of the New Testament, nearly all Jews and deeply familiar with the Septuagint, wrote in a Jewish-Greek dialect strongly influenced by Aramaic and Hebrew[146] (see Jewish Koine Greek, related to the Greek of the Septuagint). But other scholars say that this view is arrived at by comparing the linguistic style of the New Testament to the preserved writings of the literary men of the era, who imitated the style of the great Attic texts and as a result did not reflect the everyday spoken language, so that this difference in style could be explained by the New Testament being written, unlike other preserved literary material of the era, in the Koine Greek spoken in everyday life, in order to appeal to the common people, a style which has also been found in contemporary non-Jewish texts such as private letters, receipts and petitions discovered in Egypt (where the dry air has preserved these documents which, as everyday material not deemed of literary importance, had not been copied by subsequent generations).[147]

Remove ads

Development of the New Testament canon

Summarize

Perspective

The process of canonization of the New Testament was complex and lengthy. In the initial centuries of early Christianity, there were many books widely considered by the church to be inspired, but there was no single formally recognized New Testament canon.[148] The process was characterized by a compilation of books that apostolic tradition considered authoritative in worship and teaching, relevant to the historical situations in which they lived, and consonant with the Old Testament.[149] Writings attributed to the apostles circulated among the earliest Christian communities and the Pauline epistles were circulating, perhaps in collected forms, by the end of the 1st century AD.[150]

One of the earliest attempts at solidifying a canon was made by Marcion, c. 140 AD, who accepted only a modified version of Luke (the Gospel of Marcion) and ten of Paul's letters, while rejecting the Old Testament entirely. His canon was largely rejected by other groups of Christians, notably the proto-orthodox Christians, as was his theology, Marcionism. Adolf von Harnack,[151] John Knox,[152] and David Trobisch,[43] among other scholars, have argued that the church formulated its New Testament canon partially in response to the challenge posed by Marcion.

Polycarp,[153] Irenaeus[154] and Tertullian[155] held the epistles of Paul to be divinely inspired "scripture". Other books were held in high esteem but were gradually relegated to the status of New Testament apocrypha. Justin Martyr, in the mid 2nd century, mentions "memoirs of the apostles" as being read on Sunday alongside the "writings of the prophets".[156]

The Muratorian fragment, dated at between 170 and as late as the end of the 4th century (according to the Anchor Bible Dictionary), may be the earliest known New Testament canon attributed to mainstream Christianity. It is similar, but not identical, to the modern New Testament canon.

The oldest clear endorsement of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John being the only legitimate gospels was written c. 180 AD. A four gospel canon (the Tetramorph) was asserted by Irenaeus, who refers to it directly[157][158] in his polemic Against Heresies:

It is not possible that the gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the church is scattered throughout all the world, and the "pillar and ground" of the church is the gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars, breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh.[158]

— Irenaeus of Lyon (emphasis added)

The books considered to be authoritative by Irenaeus included the four gospels and many of the letters of Paul, although, based on the arguments Irenaeus made in support of only four authentic gospels, some interpreters deduce that the fourfold Gospel must have still been a novelty in Irenaeus's time.[159]

Origen (3rd century)

By the early 200s, Origen may have been using the same twenty-seven books as in the Catholic New Testament canon, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of the Letter to the Hebrews, Epistle of James, II Peter, II John and III John and the Book of Revelation,[160] known as the Antilegomena. Likewise, the Muratorian fragment is evidence that, perhaps as early as 200, there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to the twenty-seven book NT canon, which included four gospels and argued against objections to them.[161] Thus, while there was a good measure of debate in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the major writings are claimed to have been accepted by almost all Christians by the middle of the 3rd century.[162]

Origen was largely responsible for the collection of usage information regarding the texts that became the New Testament. The information used to create the late-4th-century Easter Letter, which declared accepted Christian writings, was probably based on the Ecclesiastical History (HE) of Eusebius of Caesarea, wherein he uses the information passed on to him by Origen to create both his list at HE 3:25 and Origen's list at HE 6:25. Eusebius got his information about what texts were then accepted and what were then disputed, by the third-century churches throughout the known world, a great deal of which Origen knew of firsthand from his extensive travels, from the library and writings of Origen.[163]

In fact, Origen would have possibly included in his list of "inspired writings" other texts kept out by the likes of Eusebius—including the Epistle of Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas, and 1 Clement. Notwithstanding these facts, "Origen is not the originator of the idea of biblical canon, but he certainly gives the philosophical and literary-interpretative underpinnings for the whole notion."[164]

Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History

Eusebius, c. 300, gave a detailed list of New Testament writings in his Ecclesiastical History Book 3, Chapter XXV:

- "1... First then must be put the holy quaternion of the gospels; following them the Acts of the Apostles... the epistles of Paul... the epistle of John... the epistle of Peter... After them is to be placed, if it really seem proper, the Book of Revelation, concerning which we shall give the different opinions at the proper time. These then belong among the accepted writings."

- "3 Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name. Among the rejected [Kirsopp Lake translation: "not genuine"] writings must be reckoned also the Acts of Paul, and the so-called Shepherd, and the Apocalypse of Peter, and in addition to these the extant epistle of Barnabas, and the so-called Teachings of the Apostles; and besides, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books. And among these some have placed also the Gospel according to the Hebrews... And all these may be reckoned among the disputed books."

- "6... such books as the Gospels of Peter, of Thomas, of Matthias, or of any others besides them, and the Acts of Andrew and John and the other apostles... they clearly show themselves to be the fictions of heretics. Wherefore they are not to be placed even among the rejected writings, but are all of them to be cast aside as absurd and impious."

The Book of Revelation is counted as both accepted (Kirsopp Lake translation: "recognized") and disputed, which has caused some confusion over what exactly Eusebius meant by doing so. From other writings of the church fathers, it was disputed with several canon lists rejecting its canonicity. EH 3.3.5 adds further detail on Paul: "Paul's fourteen epistles are well known and undisputed. It is not indeed right to overlook the fact that some have rejected the Epistle to the Hebrews, saying that it is disputed by the church of Rome, on the ground that it was not written by Paul." EH 4.29.6 mentions the Diatessaron: "But their original founder, Tatian, formed a certain combination and collection of the gospels, I know not how, to which he gave the title Diatessaron, and which is still in the hands of some. But they say that he ventured to paraphrase certain words of the apostle Paul, in order to improve their style."

4th century and later

In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of the books that would become the twenty-seven-book NT canon,[165] and he used the word "canonized" (kanonizomena) in regards to them.[166] The first council that accepted the present canon of the New Testament may have been the Synod of Hippo Regius in North Africa (393 AD). The acts of this council are lost. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Council of Carthage (397) and the Council of Carthage (419).[167] These councils were under the authority of St. Augustine, who regarded the canon as already closed.[168][169][170]

Pope Damasus I's Council of Rome in 382, if the Decretum Gelasianum is correctly associated with it, issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above,[165] or, if not, the list is at least a 6th-century compilation.[171] Likewise, Damasus' commissioning of the Latin Vulgate edition of the Bible, c. 383, was instrumental in the fixation of the canon in the West.[172] In c. 405, Pope Innocent I sent a list of the sacred books to a Gallic bishop, Exsuperius of Toulouse. Christian scholars assert that, when these bishops and councils spoke on the matter, they were not defining something new but instead "were ratifying what had already become the mind of the Church."[168][173][174]

The New Testament canon as it is now was first listed by St. Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, in 367, in a letter written to his churches in Egypt, Festal Letter 39. Also cited is the Council of Rome, but not without controversy. That canon gained wider and wider recognition until it was accepted at the Third Council of Carthage in 397 and 419. The Book of Revelation was not added till the Council of Carthage (419).[175]

Thus, some claim that, from the 4th century, there existed unanimity in the West concerning the New Testament canon (as it is today),[176] and that, by the 5th century, the Eastern Church, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation and thus had come into harmony on the matter of the canon.[177] Nonetheless, full dogmatic articulations of the canon were not made until the Canon of Trent of 1546 for Roman Catholicism, the Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563 for the Church of England, the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1647 for Calvinism, and the Synod of Jerusalem of 1672 for the Greek Orthodox.

On the question of NT Canon formation generally, New Testament scholar Lee Martin McDonald has written that:[178]

Although a number of Christians have thought that church councils determined what books were to be included in the biblical canons, a more accurate reflection of the matter is that the councils recognized or acknowledged those books that had already obtained prominence from usage among the various early Christian communities.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on the Canon of the New Testament: "The idea of a complete and clear-cut canon of the New Testament existing from the beginning, that is from Apostolic times, has no foundation in history. The Canon of the New Testament, like that of the Old, is the result of a development, of a process at once stimulated by disputes with doubters, both within and without the Church, and retarded by certain obscurities and natural hesitations, and which did not reach its final term until the dogmatic definition of the Tridentine Council."[179]

In 331, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius (Apol. Const. 4) recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists, and that Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus may be examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta and Codex Alexandrinus, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[180]

Remove ads

Early manuscripts

Like other literature from antiquity, the text of the New Testament was (prior to the advent of the printing press) preserved and transmitted in manuscripts. Manuscripts containing at least a part of the New Testament number in the thousands. The earliest of these (like manuscripts containing other literature) are often very fragmentarily preserved. Some of these fragments have even been thought to date as early as the 2nd century (i.e., Papyrus 90, Papyrus 98, Papyrus 104, and famously Rylands Library Papyrus P52, though the early date of the latter has recently been called into question).[181]

Remove ads

Textual variation

Summarize

Perspective

Textual criticism deals with the identification and removal of transcription errors in the texts of manuscripts. Ancient scribes made errors or alterations (such as including non-authentic additions).[182] The New Testament has been preserved in more than 5,800 Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Ethiopic and Armenian. Even if the original Greek versions were lost, the entire New Testament could still be assembled from the translations.[183]

In addition, there are so many quotes from the New Testament in early church documents and commentaries that the entire New Testament could also be assembled from these alone.[183] Not all biblical manuscripts come from orthodox Christian writers. For example, the Gnostic writings of Valentinus come from the 2nd century AD, and these Christians were regarded as heretics by the mainstream church.[184] The sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, but it also gives scholars a better idea of how close modern Bibles are to the original versions.[184]

On noting the large number of surviving ancient manuscripts, Bruce Metzger sums up the view on the issue by saying "The more often you have copies that agree with each other, especially if they emerge from different geographical areas, the more you can cross-check them to figure out what the original document was like. The only way they'd agree would be where they went back genealogically in a family tree that represents the descent of the manuscripts.[183]

Interpolations

In attempting to determine the original text of the New Testament books, some modern textual critics have identified sections as additions of material, centuries after the gospel was written. These are called interpolations. In modern translations of the Bible, the results of textual criticism have led to certain verses, words and phrases being left out or marked as not original. According to Bart D. Ehrman, "These scribal additions are often found in late medieval manuscripts of the New Testament, but not in the manuscripts of the earlier centuries."[185]

Most modern Bibles have footnotes to indicate passages that have disputed source documents. Bible commentaries also discuss these, sometimes in great detail. While many variations have been discovered between early copies of biblical texts, almost all have no importance, as they are variations in spelling, punctuation, or grammar. Also, many of these variants are so particular to the Greek language that they would not appear in translations into other languages. For example, order of words (i.e. "man bites dog" versus "dog bites man") often does not matter in Greek, so textual variants that flip the order of words often have no consequences.[183]

Outside of these unimportant variants, there are a couple variants of some importance. The two most commonly cited examples are the last verses of the Gospel of Mark[186][187][188] and the story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery in the Gospel of John.[189][190][191] Many scholars and critics also believe that the Johannine Comma reference supporting the Trinity doctrine in the First Epistle of John to have been a later addition.[192][193] According to Norman Geisler and William Nix, "The New Testament, then, has not only survived in more manuscripts than any other book from antiquity, but it has survived in a purer form than any other great book—a form that is 99.5% pure".[194]

The often referred to Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, a book written to prove the validity of the New Testament, says: "A study of 150 Greek [manuscripts] of the Gospel of Luke has revealed more than 30,000 different readings... It is safe to say that there is not one sentence in the New Testament in which the [manuscript] is wholly uniform."[195]

Biblical criticism

Biblical criticism is the scholarly "study and investigation of biblical writings that seeks to make discerning judgments about these writings."[196]

Establishing a critical text

The textual variation among manuscript copies of books in the New Testament prompted attempts to discern the earliest form of text already in antiquity (e.g., by the 3rd-century Christian author Origen). The efforts began in earnest again during the Renaissance, which saw a revival of the study of ancient Greek texts. During this period, modern textual criticism was born. In this context, Christian humanists such as Lorenzo Valla and Erasmus promoted a return to the original Greek of the New Testament. This was the beginning of modern New Testament textual criticism, which over subsequent centuries would increasingly incorporate more and more manuscripts, in more languages (i.e., versions of the New Testament), as well as citations of the New Testament by ancient authors and the New Testament text in lectionaries in order to reconstruct the earliest recoverable form of the New Testament text and the history of changes to it.[3]

Remove ads

Relationship to earlier and contemporaneous literature

Books that later formed the New Testament, like other Christian literature of the period, originated in a literary context that reveals relationships not only to other Christian writings, but also to Graeco-Roman and Jewish works. Of singular importance is the extensive use of and interaction with the Jewish Bible and what would become the Christian Old Testament. Both implicit and explicit citations, as well as countless allusions, appear throughout the books of the New Testament, from the Gospels and Acts, to the Epistles, to the Apocalypse.[197]

Remove ads

Early versions

Summarize

Perspective

The first translations (usually called "versions") of the New Testament were made beginning already at the end of 2nd century. The earliest versions of the New Testament are the translations into the Syriac, Latin, and Coptic languages.[198]

Syriac

The Philoxenian probably was produced in 508 for Bishop Philoxenus of Mabbug.[199]

Coptic

There are several dialects of the Coptic language: Bohairic (the Nile Delta), Fayyumic (in the Faiyum in Middle Egypt), Sahidic (in Upper Egypt), Akhmimic (what is now Sohag Governorate in Upper Egypt), and others. The first translation was made by at least the third century into the Sahidic dialect (copsa). This translation represents a mixed text, mostly Alexandrian, though also with Western readings.[200]

A Bohairic translation was made later, but existed already in the 4th century. Though the translation makes less use of Greek words than the Sahidic, it does employ some Greek grammar (e.g., in word-order and the use of particles such as the syntactic construction μεν—δε). For this reason, the Bohairic translation can be helpful in the reconstruction of the early Greek text of the New Testament.[201]

Other ancient translations

The continued spread of Christianity, and the foundation of national churches, led to the translation of the Bible—often beginning with books from the New Testament—into a variety of other languages at a relatively early date: Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Persian, Sogdian, and eventually Gothic, Old Church Slavonic, Arabic, and Nubian.[202]

Remove ads

Modern translations

Summarize

Perspective

The 16th century saw the rise of Protestantism and an explosion of translations of the New (and Old) Testament into the vernacular. Notable are those of Martin Luther (1522), Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (1523), the Froschau Bible (1525–1529, revised in 1574), William Tyndale (1526, revised in 1534, 1535 and 1536), the Brest Bible (1563), and the Authorized Version (also called the "King James Version") (1611).

Translations of the New Testament made since the appearance of critical editions of the Greek text (notably those of Tischendorf, Westcott and Hort, and von Soden) have largely used them as their base text. Unlike the Textus Receptus, they have a pronounced Alexandrian character. Standard critical editions are those of Nestle-Åland (the text, though not the full critical apparatus of which is reproduced in the United Bible Societies' "Greek New Testament"), Souter, Vogels, Bover and Merk.

Notable translations of the New Testament based on these most recent critical editions include the Revised Standard Version (1946, revised in 1971), La Bible de Jérusalem (1961, revised in 1973 and 2000), the Einheitsübersetzung (1970, final edition 1979), the New American Bible (1970, revised in 1986 and 2011), the New International Version (1973, revised in 1984 and 2011), the Traduction Oecuménique de la Bible (1988, revised in 2004), the New Revised Standard Version (1989) and the English Standard Version (2001, revised in 2007, 2011 and 2016).

Theological interpretation in Christian churches

Summarize

Perspective

According to Gary T. Meadors:

The self-witness of the Bible to its inspiration demands a commitment to its unity. The ultimate basis for unity is contained in the claim of divine inspiration in 2 Timothy 3:16[203] that "all Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness" (KJV). The term "inspiration" renders the Greek word theopneustos. This term only occurs here in the New Testament and literally means "God-breathed" (the chosen translation of the NIV).[204]

Unity in diversity

The notion of unity in diversity of Scripture claims that the Bible presents a noncontradictory and consistent message concerning God and redemptive history. The fact of diversity is observed in comparing the diversity of time, culture, authors' perspectives, literary genre, and the theological themes.[204]

Studies from many theologians considering the "unity in diversity" to be found in the New Testament (and the Bible as a whole) have been collected and summarized by New Testament theologian Frank Stagg. He describes them as some basic presuppositions, tenets, and concerns common among the New Testament writers, giving to the New Testament its "unity in diversity":

- The reality of God is never argued but is always assumed and affirmed

- Jesus Christ is absolutely central: he is Lord and Savior, the foretold Prophet, the Messianic King, the Chosen, the way, the truth, and the light, the One through whom God the Father not only acted but through whom He came

- The Holy Spirit came anew with Jesus Christ.

- The Christian faith and life are a calling, rooted in divine election.

- The plight of everyone as sinner means that each person is completely dependent upon the mercy and grace of God

- Salvation is both God's gift and his demand through Jesus Christ, to be received by faith

- The death and resurrection of Jesus are at the heart of the total event of which he was the center

- God creates a people of his own, designated and described by varied terminology and analogies

- History must be understood eschatologically, being brought along toward its ultimate goal when the kingdom of God, already present in Christ, is brought to its complete triumph

- In Christ, all of God's work of creation, revelation, and redemption is brought to fulfillment[205]

Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Classical Anglicanism

For the Roman Catholic Church, there are two modes of Revelation: Scripture and Tradition. Both of them are interpreted by the teachings of the Church. The Roman Catholic view is expressed clearly in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1997):

§ 82: As a result the Church, to whom the transmission and interpretation of Revelation is entrusted, does not derive her certainty about all revealed truths from the holy Scriptures alone. Both Scripture and Tradition must be accepted and honoured with equal sentiments of devotion and reverence.

§ 107: The inspired books teach the truth. Since therefore all that the inspired authors or sacred writers affirm should be regarded as affirmed by the Holy Spirit, we must acknowledge that the books of Scripture firmly, faithfully, and without error teach that truth which God, for the sake of our salvation, wished to see confided to the Sacred Scriptures.

In Catholic terminology the teaching office is called the Magisterium. The Catholic view should not be confused with the two-source theory. As the Catechism states in §§ 80 and 81, Revelation has "one common source ... two distinct modes of transmission."[4]

While many Eastern Orthodox writers distinguish between Scripture and Tradition, Bishop Kallistos Ware says that for the Orthodox there is only one source of the Christian faith, Holy Tradition, within which Scripture exists.[206]

Traditional Anglicans believe that "Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation", (Article VI), but also that the Catholic Creeds "ought thoroughly to be received and believed" (Article VIII), and that the Church "hath authority in Controversies of Faith" and is "a witness and keeper of Holy Writ" (Article XX).[207]

In the famous words of Thomas Ken, Bishop of Bath and Wells: "As for my religion, I dye in the holy catholic and apostolic faith professed by the whole Church before the disunion of East and West, more particularly in the communion of the Church of England, as it stands distinguished from all Papal and Puritan innovations, and as it adheres to the doctrine of the Cross."[This quote needs a citation]

Protestantism

Following the doctrine of sola scriptura, Protestants believe that their traditions of faith, practice and interpretations carry forward what the scriptures teach, and so tradition is not a source of authority in itself. Their traditions derive authority from the Bible, and are therefore always open to reevaluation. This openness to doctrinal revision has extended in Liberal Protestant traditions even to the reevaluation of the doctrine of Scripture upon which the Reformation was founded, and members of these traditions may even question whether the Bible is infallible in doctrine, inerrant in historical and other factual statements, and whether it has uniquely divine authority. The adjustments made by modern Protestants to their doctrine of scripture vary widely.[citation needed]

American evangelical and fundamentalist Protestantism

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (May 2025) |

Within the US, the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (1978) articulates evangelical views on this issue.[citation needed][according to whom?] Paragraph four of its summary states: "Being wholly and verbally God-given, Scripture is without error or fault in all its teaching, no less in what it states about God's acts in creation, about the events of world history, and about its own literary origins under God, than in its witness to God's saving grace in individual lives."[5]

American mainline and liberal Protestantism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (May 2025) |

Officials of the Presbyterian Church USA report: "We acknowledge the role of scriptural authority in the Presbyterian Church, but Presbyterians generally do not believe in biblical inerrancy. Presbyterians do not insist that every detail of chronology or sequence or prescientific description in scripture be true in literal form. Our confessions do teach biblical infallibility. Infallibility affirms the entire truthfulness of scripture without depending on every exact detail."[208]

Messianic Judaism

Messianic Judaism generally holds the same view of New Testament authority as evangelical Protestants.[209] According to the view of some Messianic Jewish congregations, Jesus did not annul the Torah, but that its interpretation is revised and ultimately explained through the Apostolic Scriptures.[210]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses accept the New Testament as divinely inspired Scripture, and as infallible in every detail, with equal authority as the Hebrew Scriptures. They view it as the written revelation and good news of the Messiah, the ransom sacrifice of Jesus, and the Kingdom of God, explaining and expounding the Hebrew Bible, not replacing but vitally supplementing it. They also view the New Testament as the primary instruction guide for Christian living, and church discipline. They generally call the New Testament the "Christian Greek Scriptures", and see only the "covenants" as "old" or "new", but not any part of the actual Scriptures themselves.[211]

United Pentecostals

Oneness Pentecostalism subscribes to the common Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. They view the Bible as the inspired Word of God, and as absolutely inerrant in its contents (though not necessarily in every translation).[212][213] They regard the New Testament as perfect and inerrant in every way, revealing the Lord Jesus Christ in the Flesh, and his Atonement, and which also explains and illuminates the Old Testament perfectly, and is part of the Bible canon, not because church councils or decrees claimed it so, but by witness of the Holy Spirit.[214][215]

Seventh-day Adventists

The Seventh-day Adventist Church holds the New Testament as the inspired Word of God, with God influencing the "thoughts" of the Apostles in the writing, not necessarily every word though. The first fundamental belief of the Seventh-Day Adventist church stated that "The Holy Scriptures are the infallible revelation of [God's] will." Adventist theologians generally reject the "verbal inspiration" position on Scripture held by many conservative evangelical Christians. They believe instead that God inspired the thoughts of the biblical authors and apostles, and that the writers then expressed these thoughts in their own words.[216] This view is popularly known as "thought inspiration", and most Adventist members hold to that view. According to Ed Christian, former JATS editor, "few if any ATS members believe in verbal inerrancy".[217]

How the Mosaic Law should be applied came up at Adventist conferences in the past, and Adventist theologians such as A. T. Jones and E. J. Waggoner looked at the problem addressed by Paul in Galatians as not the ceremonial law, but rather the wrong use of the law (legalism). They were opposed by Uriah Smith and George Butler at the 1888 Conference. Smith in particular thought the Galatians issue had been settled by Ellen White already, yet in 1890 she claimed that justification by faith is "the third angel's message in verity."[218] White interpreted Colossians 2:14[219] as saying that the ceremonial law was nailed to the cross.[220]

Latter-day Saints

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) believe that the New Testament, as part of the Christian biblical canon, is accurate "as far as it is translated correctly".[221] They believe the Bible as originally revealed is the word of God, but that the processes of transcription and translation have introduced errors into the texts as currently available, and therefore they cannot be regarded as completely inerrant.[222][223] In addition to the Old and New Testaments, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price are considered part of their scriptural canon.[224][225]

In the arts

Summarize

Perspective

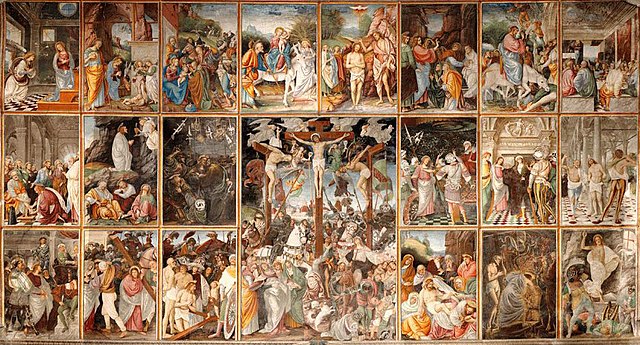

Most of the influence of the New Testament upon the arts has come from the Gospels and the Book of Revelation.[citation needed] Literary expansion of the Nativity of Jesus found in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke began already in the 2nd century, and the portrayal of the Nativity has continued in various art forms to this day. The earliest Christian art would often depict scenes from the New Testament such as the raising of Lazarus, the baptism of Jesus or the motif of the Good Shepherd.

Biblical paraphrases and poetic renditions of stories from the life of Christ (e.g., the Heliand) became popular in the Middle Ages, as did the portrayal of the arrest, trial and execution of Jesus in Passion plays. Indeed, the Passion became a central theme in Christian art and music. The ministry and Passion of Jesus, as portrayed in one or more of the New Testament Gospels, has also been a theme in film, almost since the inception of the medium (e.g., La Passion, France, 1903).

See also

- Authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews

- Catalogue of Vices and Virtues

- Chronology of Jesus

- Earlier Epistle to the Ephesians Non-canonical books referenced in the New Testament

- Historical background of the New Testament

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- List of Gospels

- Novum Testamentum Graece

Notes

- Ancient Greek: Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. Hē Kainḕ Diathḗkē; Latin: Novum Testamentum; Hebrew: הברית החדשה.

- For example, the pact between Jacob with Laban in Genesis (Genesis 31:44).

- For example, the covenant at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:5) or the "new covenant" verse from Jeremiah 31:31 above (Jeremiah 31:31).

- See also Tertullian, Against Marcion, Book IV, chapters I, II, XIV. His meaning in chapter XX is less clear, and in chapters IX and XL he uses the term to mean 'new covenant'.

- Joseph Barber Lightfoot in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians writes: "At this point[45] the apostle takes the pen from his amanuensis, and the concluding paragraph is written with his own hand. From the time when letters began to be forged in his name[46] it seems to have been his practice to close with a few words in his own handwriting, as a precaution against such forgeries.... In the present case he writes a whole paragraph, summing up the main lessons of the epistle in terse, eager, disjointed sentences. He writes it, too, in large, bold characters (Gr. pelikois grammasin), that his handwriting may reflect the energy and determination of his soul."[47]

- The Gospels are in this order in many Old Latin manuscripts, as well as in the Greek manuscripts Codex Bezae and Codex Washingtonianus.

- See also the article on the Antilegomena.

- A glance at recent extended treatments of the "we" passages and commentaries demonstrates that, within biblical scholarship, solutions in the historical eyewitness traditions continue to be the most influential explanations for the first-person plural style in Acts. Of the two latest full-length studies on the "we" passages, for example, one argues that the first-person accounts came from Silas, a companion of Paul but not the author, and the other proposes that first-person narration was Luke's (Paul's companion and the author of Acts) method of communicating his participation in the events narrated.[73]

- Donald Guthrie lists the following scholars as supporting authenticity: Wohlenberg, Lock, Meinertz, Thörnell, Schlatter, Spicq, Jeremias, Simpson, Kelly, and Fee[105]

- Sanders (2010): "John, however, is so different that it cannot be reconciled with the Synoptics except in very general ways [...] Scholars have unanimously chosen the Synoptic Gospels' version of Jesus' teaching [...] The Synoptic Gospels, then, are the primary sources for knowledge of the historical Jesus. They are not, however, the equivalent of an academic biography of a recent historical figure. Instead, the Synoptic Gospels are theological documents that provide information the authors regarded as necessary for the religious development of the Christian communities in which they worked."

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads