Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Leaving group

Atom(s) that detach from the substrate during a chemical reaction From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

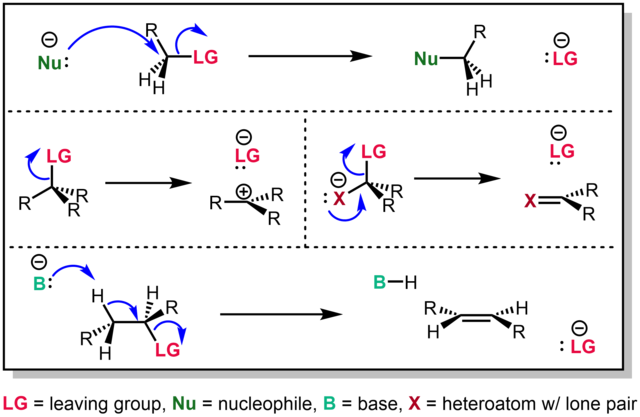

In organic chemistry, a leaving group typically means a molecular fragment that departs with an electron pair during a reaction step with heterolytic bond cleavage. In this usage, a leaving group is a less formal but more commonly used synonym of the term nucleofuge; although IUPAC gives the term a broader definition.

A species' ability to serve as a leaving group can affect whether a reaction is viable, as well as what mechanism the reaction takes.

Leaving group ability depends strongly on context, but often correlates with ability to stabilize additional electron density from bond heterolysis. Common anionic leaving groups are Cl−, Br− and I− halides and sulfonate esters such as tosylate (TsO−). Water (H2O), alcohols (R−OH), and amines (R3N) are common neutral leaving groups, although they often require activating catalysts. Some moieties, such as hydride (H−) serve as leaving groups only extremely rarely.

Remove ads

Nomenclature

IUPAC defines a leaving group to be any group of atoms that detaches from the main substrate during a reaction step.[1] The term thus includes groups that depart without an electron pair in a heterolytic cleavage (electrofuges), like H+ or SiR+3, which commonly depart in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions.[1][2] Similarly, species of high thermodynamic stability like nitrogen (N2) or carbon dioxide (CO2) commonly act as leaving groups in homolytic bond cleavage reactions of radical species.

In organic chemistry, the term leaving group is rarely used for such species, being restricted only to nucleofugal leaving groups.[3] Leaving groups are generally anions or neutral species, departing from neutral or cationic substrates, respectively, though in rare cases, cations leaving from a dicationic substrate are also known.[4]

This article follows the organic chemistry convention.

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

Leaving group ability manifests physically in a fast reaction rate. Equivalently, reactions involving good leaving groups have low activation barriers and relatively stable transition states. Because different reaction mechanisms have different transition states, leaving group ability depends on the reaction in question.

For example, consider the first step of an SN1 or E1 reaction in neutral media: ionization, with an anionic leaving group.

Because the leaving group gains negative charge in the transition state (and products), a good leaving group must stabilize this negative charge and form a stable anion. Strong bases such as OH−, OR− and NR−2 tend to make poor leaving groups, as they cannot stabilize further negative charge; whereas extremely weak bases, such as OSO2CH−

3, leave easily. Mathematically, leaving groups typically exhibit Bell–Evans–Polanyi correlation between the dissociation constant for their conjugate acid (pKaH) and lability.[citation needed]

Context-dependence

The correlation in SN1 and E1 reactions between leaving group ability and pKaH is not perfect. Leaving group ability reflects the energy difference (ΔG‡) between neutral starting materials and the partially-charged, partially-bonded transition state. The pKaH, however, represents net energy difference (ΔG°) for the (possibly multi-step) adduction equilibrium between the leaving group and a solvated proton. Hammond's postulate explains conceptually when and why the two energy differences correlate.[citation needed]

For reactions with a different transition state, other aspects of the leaving group may govern. In acid-catalyzed reactions' rate-determining step, only adducts between the formal leaving group and the acid catalyst depart. In those cases, leaving group ability correlates with bond strength to the catalyst (see § Leaving group activation). Even more dramatically, benzoate anions decarboxylate when heated with a copper salt catalyst, in principle expulsing an aryl anion from CO2. The true leaving group is most likely an arylcopper compound rather than the aryl anion salt.[citation needed]

Even for the same reaction mechanism in the same media, relative lability may depend on the other reagents. In the substitutions tabulated below, ethoxide displaces tosylate before any halide, but para-thiocresolate prefers to displace iodide and even bromide before tosylate.[5]

| Leaving group (X) |  |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cl | 0.0074 | 0.0024 (at 40 °C) |

| Br | 1 | 1 |

| I | 3.5 | 1.9 |

| OTs | 0.44 | 3.6 |

Remove ads

Table

Many organic chemistry textbooks offer a table comparing typical leaving groups' ability across common reactions:

| Leaving groups ordered approximately in decreasing ability to leave[6] | |

|---|---|

| R−N+2 | dinitrogen |

| R−OR'+2 | dialkyl ether |

| R−OSO2RF | perfluoroalkylsulfonates (e.g. triflate) |

| R–I | iodide |

| R–OTs, R–OMs, etc. | tosylates, mesylates and similar sulfonates |

| R–Br | bromide |

| R−OH+2, R'−OHR+ | water, alcohols |

| R–Cl | chloride |

| R−ONO2, R−OPO(OR')2 | nitrate, phosphate, and other inorganic esters |

| R−SR'+2 | thioether |

| R−NR'+3, R−NH+3 | amines, ammonia |

| R–F | fluoride |

| R–OCOR | carboxylate |

| R–OAr | phenoxides |

| R–OH, R–OR | hydroxide, alkoxides |

| R–NR2 | amides |

| R–H | hydride |

| R–R' | arenide, alkanide |

It is exceedingly rare for groups such as H− (hydrides), R3C− (alkyl anions, R = alkyl or H), or Ar− (aryl anions, Ar = aryl) to depart with a pair of electrons because of the high energy of these species. The Chichibabin reaction provides an example of hydride as a leaving group, while the Wolff-Kishner reaction and Haller-Bauer reaction feature unstabilized carbanion leaving groups.

SN2 reactions

For SN2 reactions, typical synthetically-useful leaving groups include Cl−, Br−, I−, −OTs, −OMs, −OTf, and H2O. Phosphate and carboxylate substrates are more likely to react by competitive addition-elimination, while sulfonium and ammonium salts generally form ylides or undergo E2 elimination. Phenoxides (−OAr) constitute the lower limit for feasible SN2 leaving groups: very strong nucleophiles like Ph2P− or EtS− demethylate anisole derivatives through SN2 displacement at the methyl group. Hydroxide, alkoxides, amides, hydride, and alkyl anions do not serve as leaving groups in SN2 reactions.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Basic eliminations

Summarize

Perspective

When anionic or dianionic tetrahedral intermediates collapse, the high electron density of the neighboring heteroatom facilitates the expulsion of even a very poor leaving group. This dramatic departure occurs because forming a very strong C=O double-bond can drive an otherwise unfavorable reaction forward.[citation needed] For example, even amides expulse R2N−, an extremely poor leaving group, in nucleophilic acyl substitution.

This elimination of poor leaving groups also extends vinylogously to conjugate base eliminations. Many E1cb reactions (e.g. the aldol condensation) commonly involve a hydroxide leaving group from an enolate β position.

Likewise, in SNAr reactions, the rate is generally increased when the leaving group is fluoride relative to the other halogens. This effect is due to the fact that the highest energy transition state for this two step addition-elimination process occurs in the first step, where fluoride's greater electron withdrawing capability relative to the other halides stabilizes the developing negative charge on the aromatic ring. The departure of the leaving group takes place quickly from this high energy Meisenheimer complex, and since the departure is not involved in the rate limiting step, it does not affect the overall rate of the reaction.[7][page needed]

E1cb reactions

E1cb reactions proceed with poor leaving groups, but because the C=C double bond is weaker than a C=O bond, the leaving group affects the elimination mechanism.

Poor leaving groups favor the E1cB mechanism, but as the leaving group improves, transition state BC‡ becomes lower in energy. First, the rate-determining step shifts: initially leaving-group elimination from intermediate B; it becomes deprotonation via transition state AB‡ (not pictured). Eventually, BC‡ is no longer stationary on the potential energy surface, and the reaction becomes a concerted E2 elimination (albeit very asynchronous in the diagrammed case).[citation needed]

Remove ads

Activation

In SN1 and E1 reactions, protonation or complexation with a Lewis acid commonly transform a poor leaving group into a good one. Then the reaction proceeds with (respectively) nucleophilic attack or elimination. For example, protonation before departure allows a molecule to formally lose such poor leaving groups as hydroxide.

The same principle is applies in Friedel-Crafts reactions. There, a strong Lewis acid is required to generate a carbocation from an alkyl halide or an acylium ion from an acyl halide.

In Friedel-Crafts alkylations, the normal halogen leaving group order is reversed, and the reaction rate follows RF > RCl > RBr > RI. This effect is due to their greater ability to complex the Lewis acid catalyst. The actual group that leaves is an "ate" complex between the Lewis acid and the formal leaving group.[8]

Remove ads

Spontaneous departures

Summarize

Perspective

Any leaving group comparable to triflate is called a super leaving group; such compounds generally autoionize if the electrofuge can form a stable carbocation.[citation needed] Thus, the most commonly encountered organic triflates are alkenyl, aryl, and methyl triflates, of which none can form stable carbocations. Conversely, mixed acyl-triflyl anhydrides smoothly undergo Friedel-Crafts acylation,[9] where the corresponding acyl halides would require a strong Lewis acid catalyst.

Even more reactive are the hyper leaving groups, which are stronger than triflate and react with reductive elimination. Prominent hyper leaving groups include various halonium ions,[10] such as diaryl iodonium salts; and other λ3-iodanes.

Hyper leaving groups can be displaced by extraordinarily weak nucleophiles, in part because entropy favors splitting one molecule into three.[citation needed] Heating neat samples of (CH3)2Cl+ [CHB11Cl11]− under reduced pressure methylated the very poorly nucleophilic carborane anion, with concomitant expulsion of the CH3Cl leaving group.[11] Likewise, dialkylhalonium hexafluoroantimonate salts alkylate other alkyl halides to give exchanged products.[12]

In one study, reactivities increased in the order chloride (krel = 1), iodide (krel = 91), tosylate (krel = 3.7×104), triflate (krel = 1.4×108), phenyliodonium tetrafluoroborate (PhI+ BF−4, krel = 1.2×1014).[citation needed] In general, leaving groups from dialkylhalonium ions increase in lability as RI < RBr < RCl.[citation needed]

Remove ads

See also

- Entering group (a relatively uncommon term) — a species that bonds to a substrate-derived intermediate.

- Electrofuge

- Electrophile

- Elimination reaction

- Nucleofuge

- Nucleophile

- Substitution reaction

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads