Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

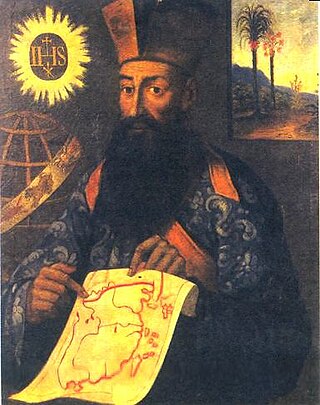

Martino Martini

Jesuit missionary, cartographer and historian (1614–1661) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Martino Martini (20 September 1614 – 6 June 1661) was a Jesuit missionary in China. Born and raised in Trento, he worked as a cartographer and historian of ancient imperial China.[1]

Remove ads

Early years

Martini was born in Trento, in the Bishopric of Trent, Holy Roman Empire. After finishing high school in Trento in 1631, he joined the Society of Jesus, continuing his studies of classical literature and philosophy at the Roman College in Rome (1634–1637). However, his main interest was astronomy and mathematics, which he studied under the supervision of Athanasius Kircher. His request to undertake missionary work in China was eventually approved by Mutius Vitelleschi, the then Superior General of the Jesuits. He pursued his theological studies in Portugal (1637–1639), where he was ordained priest (1639, in Lisbon).

Remove ads

In the Chinese Empire

Summarize

Perspective

He set out for China in 1640 and arrived in Portuguese Macau in 1642 where he studied Chinese for some time. In 1643 he crossed the border and settled in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, from where he did much travelling in order to gather scientific information, especially on the geography of the Chinese empire: he visited several provinces, as well as Peking and the Great Wall. He made great use of his talents as missionary, scholar, writer and superior.

Soon after Martini's arrival to China, the Ming capital Beijing fell to Li Zicheng's rebels (April 1644) and then to the Qing dynasty, and the last legitimate Ming emperor, the Chongzhen Emperor, hanged himself. Down in Zhenjiang, Martini continued working with the short-lived regime of Zhu Yujian, Prince of Tang, who set himself up as the (Southern) Ming Longwu Emperor. Soon enough, the Qing troops reached Zhejiang. According to Martini's report (which appeared in some editions of his De bello tartarico), the Jesuit was able to switch his allegiance to China's new masters in an easy but bold, way. When Wenzhou, in southern Zhejiang, where Martini happened to be on a mission for Zhu Yujian, was besieged by the Qing and was about to fall, the Jesuit decorated the house where he was staying with a large red poster with seven characters saying, "Here lives a doctor of the divine Law who has come from the Great West". Under the poster he set up tables with European books, astronomical instruments, etc., surrounding an altar with an image of Jesus. When the Qing troops arrived, their commander was sufficiently impressed with the display to approach Martini politely and ask if he wished to switch his loyalty to the new Qing Dynasty. Martini agreed and had his head shaved in the Manchu way, and his Chinese dress and hat were replaced with Qing-style ones. The Qing then allowed him to return to his Hangzhou church and provided him and the Hangzhou Christian community with the necessary protection.[2]

Remove ads

The Chinese Rites affair

Summarize

Perspective

In 1651 Martini left China for Rome as the Delegate of the Chinese Mission Superior. He took advantage of the long, adventurous voyage (going first to the Philippines, from thence on a Dutch privateer to Bergen, Norway,[3] which he reached on 31 August 1653, and then to Amsterdam). Further, and still on his way to Rome, he met printers in Antwerp, Vienna and Munich to submit to them historical and cartographic data he had prepared. The works were printed and made him famous.

When passing through Leyden, Martini was met by Jacobus Golius, a scholar of Arabic and Persian at the university there. Golius did not know Chinese, but had read about "Cathay" in Persian books, and wanted to verify the truth of the earlier reports of Jesuits such as Matteo Ricci and Bento de Góis who believed that Cathay was the same place as China, where they lived or, visited. Golius was familiar with the discussion of the "Cathayan" calendar in Zij-i Ilkhani, a work by the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, completed in 1272. When Golius met Martini (who, of course, knew no Persian), the two scholars found that the names of the 12 divisions into which, according to Nasir al-Din, the "Cathayans" were dividing the day, as well as those of the 24 sections of the year reported by Nasir al-Din matched those that Martini had learned in China. The story, soon published by Martini in the "Additamentum" to his Atlas of China, seemed to have finally convinced most European scholars that China and Cathay were the same.[4]

On his way to Rome, Martini met his then 10-year-old cousin Eusebio Kino who later became another famed Jesuit missionary explorer and the world-renowned cartographer of New Spain.

In the spring of 1655 Martini reached Rome. There, in Rome, was the most difficult part of his journey. He had brought along (for the Holy Office of the Church) a long and detailed communication from the Jesuit missionaries in China, in defence of their inculturated missionary and religious approach: the so-called Chinese Rites (Veneration of ancestors, and other practices allowed to new Christians). Discussions and debates took place for five months, at the end of which the Propaganda Fide issued a decree in favour of the Jesuits (23 March 1656). A battle was won, but the controversy did not abate.

Remove ads

Return to China

Summarize

Perspective

In 1658, after a most difficult journey, he was back in China with the favourable decree. He was again involved in pastoral and missionary activities in the Hangzhou area where he built a three naves church that was considered to be one of the most beautiful in the country (1659–1661). The church was hardly built when he died of cholera (1661). David E. Mungello wrote that he died of rhubarb overdosing which aggravated his constipation.[5]

Travels

Martini travelled in at least fifteen countries in Europe and seven provinces of the Chinese empire, making stops in India, Java, Sumatra, the Philippines and South Africa. After studying in Trento and Rome, Martini reached Genoa, Alicante, Cádiz, Sanlucar de Barrameda (a port near to Seville in Spain), Seville, Evora and Lisbon (Portugal), Goa (in the western region of India), Surat (a port in the northwestern region of India), Macao (on the China's southern coast, administrated by the Portuguese), Guangzhou (the capital of Guangdong Province), Nanxiong (in northern Guangdong province, between the mountains), Nanchang (the capital of Jiangxi Province), Jiujiang (in northwest Jiangxi Province), Nanjing, Hangzhou (the capital of Zhejiang Province) and Shanghai.

Traversing the Shandong Province he reached Tianjin and Beijing, Nanping in the Fujian Province, Wenzhou (in southern Zhejiang Province), Anhai (a port in southern Fujian), Manila (in the Philippines), Makassar (Sulawesi island in the Dutch Indonesia), Batavia/Jakarta (Sumatra island, capital of the Dutch Indonesia), Cape Town/Kaapstad (a stop of twenty days in the fort, the Dutch Governor Jan van Riebeeck had built in 1652), Bergen, Hamburg, the Belgian Antwerp and Brussels where he met the archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, the Dutch Leiden (with the scholar Jacobus Golius) and Amsterdam, where he met the famous cartographer Joan Blaeu.

He reached almost certainly some cities in France, then Monaco di Baviera, Vienna and the nearby Hunting Pavilion of Ebersdorf (where he met the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III of Habsburg), and finally Rome. For his last journey (from 11 January 1656 to 17 July 1658) Martini sailed from Genoa, the Hyeres islands on the French Riviera (to escape pirates), to Alicante, Lisboa, Goa, the Portuguese colony of Larantuka in Flores Island (Indonesia) resting over a month, Makassar (where he met a Dominican friar, Domingo Navarrete), Macao, and finally Hangzhou, where he died.[6]

Remove ads

Post-mortem phenomenon

According to the attestation of Prospero Intorcetta (in Litt. Annuae, 1861), Martini's corpse was found to be undecayed after twenty years. It became a longstanding object of cult, not only for Christians, until, in 1877, suspecting idolatry, the hierarchy had it reburied.[7]

Modern views

Today's scientists have shown increasing interest in the works of Martini. During an international convention organized in the city of Trento (his birthplace), a member of the Chinese academy of Social Sciences, Prof. Ma Yong said: "Martini was the first to study the history and geography of China with rigorous scientific objectivity; the extent of his knowledge of the Chinese culture, the accuracy of his investigations, the depth of his understanding of things Chinese are examples for the modern sinologists". Ferdinand von Richthofen calls Martini "the leading geographer of the Chinese mission, one who was unexcelled and hardly equalled, during the XVIII century ... There was no other missionary, either before or after, who made such diligent use of his time in acquiring information about the country". (China, I, 674 sq.)[citation needed]

Remove ads

Works

- Martini's most important work is Novus Atlas Sinensis, which appeared as part of volume 10 of Joan Blaeu's Atlas Maior (Amsterdam 1655). This work, a folio with 17 maps and 171 pages of text was, in the words of the early 20th-century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, the most complete geographical description of China that we possess, and through which Martini has become the father of geographical learning on China. The French Jesuits of the time concurred, saying that even du Halde's monumental Description...de la Chine did not fully supersede Martini's work.[8][9] The maps were reprinted in the 1659 Geographica Blaviana and the 1690 Atlas van der Hagen.

- Of the great chronological work which Martini had planned, and which was to comprise the whole Chinese history from the earliest age, only the first part appeared: Sinicæ Historiæ Decas Prima (Munich 1658), which reached until the birth of Jesus.

- His De Bello Tartarico Historia (Antwerp 1654) is also important as Chinese history, for Martini himself had lived through the frightful occurrences which brought about the overthrow of the ancient Ming dynasty. The works have been repeatedly published and translated into different languages. There is also a later version, entitled Regni Sinensis a Tartaris devastati enarratio (1661); compared to the original De Bello Tartarica Historia, it has some additions, such as an index.

- Interesting as missionary history is his Brevis Relatio de Numero et Qualitate Christianorum apud Sinas, (Brussels, 1654).

- Besides these, Martini wrote a series of theological and apologetical works in Chinese, including a De Amicitia (Hangzhou, 1661) that could have been the first anthology of Western authors available in China (Martini's selection drew mainly from Roman and Greek writings).

- Grammatica Linguae Sinensis (1652–1653). The first manuscript grammar of Mandarin Chinese and the first grammar of the Chinese language ever printed and published in M. Thévenot Relations des divers voyages curieux (1696)[10]

- Several works, among them a Chinese translation of the works of Francisco Suarez, which has not been found yet.

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads