Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Moncef Marzouki

President of Tunisia from 2011 to 2014 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

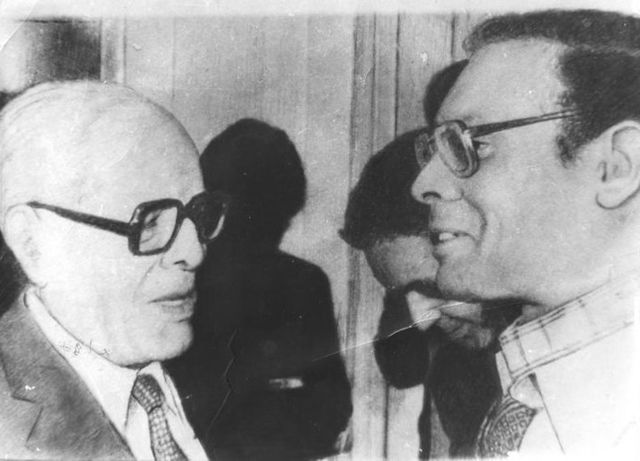

Mohamed Moncef Marzouki (Arabic: محمد المنصف المرزوقي; Muhammad al-Munṣif al-Marzūqī, born 7 July 1945) is a Tunisian politician who served as the third president of Tunisia from 2011[1][2][3] to 2014. Through his career he has been a human rights activist, physician and politician. On 12 December 2011, he was elected president of Tunisia by the Constituent Assembly.

Remove ads

Early life

Born in Grombalia, Tunisia, Marzouki was the son of a Qadi. His father, being a supporter of Salah Ben Youssef (Bourguiba's opponent), emigrated to Morocco in the late 1950s because of political pressures.[4] Marzouki finished his secondary education in Tangier, where he obtained the Baccalauréat in 1961.[4] He then went to study medicine at the University of Strasbourg in France. Returning to Tunisia in 1979, he founded the Center for Community Medicine in Sousse and the African Network for Prevention of Child Abuse, also joining Tunisian League for Human Rights.[5] In his youth, he had travelled to India to study Mahatma Gandhi's non-violent resistance.[6] Later, he also travelled to South Africa to study its transition from apartheid.[7]

Remove ads

Political career

Summarize

Perspective

When the government cracked down violently on the Islamist Ennahda Movement in 1991, Marzouki confronted Tunisian President Ben Ali calling on him to adhere to the law.[7] In 1993, Marzouki was a founding member of the National Committee for the Defense of Prisoners of Conscience, but he resigned after it was taken over by supporters of the government. He was arrested on several occasions on charges relating to the propagation of false news and working with banned Islamist groups. He subsequently founded the National Committee for Liberties. He became President[5] of the Arab Commission for Human Rights and as of 17 January 2011[ref] continues as a member of its executive board.[8]

In 2001, he founded the Congress for the Republic.[9][10] This political party was banned in 2002, but Marzouki moved to France and continued running it.[5]

Following President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali's departure from Tunisia and the Tunisian revolution, Marzouki announced his return to Tunisia and his intention to run for the presidency.[5]

President of Tunisia

On 12 December 2011, the Constituent Assembly of Tunisia, a body elected to govern the country and draft a new constitution, elected Marzouki as interim president, with 155 votes for, 3 against, and 42 blank votes.[11][12] Blank votes were the result of a boycott from the opposition parties, who considered the new mini-constitution of the country an undemocratic one. He was the first president who was not an heir to the legacy of the country's founding president, Habib Bourguiba.

On 14 December, one day after his accession to office, he appointed Hamadi Jebali of the moderate Islamist Ennahda Movement as Prime Minister.[13] Jebali presented his government on 20 December.[14]

On 3 May 2012, Nessma TV owner Nabil Karoui and two others were convicted of "blasphemy" and "disturbing public order". The charges stemmed from the network's decision to broadcast a dubbed version of the 2007 Franco-Iranian film Persepolis, which includes several visual depictions of God. Karoui was fined 2,400 dinars for the broadcast, while the station's programming director and the president of the women's organization which provided dubbing for the film were fined 1,200 dinars.[15] Responding to the verdict, Marzouki stated to members of the press in the presidential palace in Tunis, "I think this verdict is bad for the image of Tunisia. Now people in the rest of the world will only be talking about this when they talk about Tunisia."[16]

As President, Marzouki played a leading role in establishing Tunisia's Truth and Dignity Commission in 2014, as a key part of creating a national reconciliation.[17]

In March 2014, President Marzouki lifted the state of emergency that had been in place since the outbreak of the 2011 revolution, and a top military chief said soldiers stationed in some of the country's most sensitive areas would return to their barracks. The decree from President Marzouki said the state of emergency ordered in January 2011 is lifted across the country immediately. The state of emergency was imposed by longtime President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and maintained after he was overthrown. It was repeatedly renewed.[18]

In April 2014, he cut his pay by two-thirds, citing the state's need to be a model in dealing with the deteriorating financial situation.[19]

Marzouki was defeated by Beji Caid Essebsi in the November–December 2014 presidential election, and Essebsi was sworn in as President on 31 December 2014, succeeding Marzouki.[20]

Remove ads

Post-presidency

Summarize

Perspective

On 25 June 2015, Marzouki participated in the Freedom Flotilla III to the Gaza Strip. On 29 June, during their approach to the territorial waters of Gaza, but while still in international waters, the flotilla was intercepted by the Israeli navy and taken to the port of Ashdod, where the participants were interviewed. Marzouki was greeted by a delegation of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, but he declined to talk with them. On 30 June, he was deported to Paris and returned to Tunis on 1 July, where he was greeted by hundreds of supporters.[21] In 2016, he was appointed by the African Union to oversee the Comorian presidential election.[22] On 14 October 2021, the Tunisia government under Kais Saied stripped Marzouki of his diplomatic passport.[23] In November 2021, Moncef Marzouki was the subject of an international arrest warrant issued by the Tunisian government for endangering state security.[24] On 23 December 2021, Marzouki was sentenced to four years in prison and was found guilty of “undermining the security of the state from abroad” and of having caused “diplomatic harm”. Marzouki rejected the ruling, describing it as illegal, saying it was “issued by an illegitimate president who overturned the constitution”.[25][26]

On 29 December 2021, Marzouki vowed to return to Tunisia and "overthrow the incumbent regime".[27] In January 2022, Marzouki was among 19 predominantly high-ranking politicians to be referred to court for trial by the Tunisian judiciary for "electoral violations" allegedly committed during the 2019 presidential elections.[28]

In 2022 Marzouki was sentenced to 4 years in prison in absentia for “assaulting” the security of the state.[29] In 2024, he received another eight-year sentence in absentia for remarks that were interpreted by authorities as incitement and calling for the overthrow of the government.[30] In June 2025, Marzouki was sentenced in absentia by the Tunis Court of First Instance to 22 years' imprisonment on terrorism charges.[31]

Remove ads

Personal life

- From a first marriage, Moncef Marzouki has two daughters: Myriam and Nadia.[32] Myriam, a former student of the École Normale Supérieure de Paris (ENS-SHS) and an agrégée in philosophy, is a director and artistic director of a theater company.[33] His younger daughter, Nadia, obtained a PhD in political science from Sciences Po in 2008. As a research fellow at the CNRS,[34] her research focuses on religious expertise.[35] The Franco-Tunisian businessman Lotfi Bel Hadj is his nephew.[36]

In December 2011, during a private civil ceremony in Carthage Palace, he married Beatrix Rhein, a French physician.[37]

He owns a house in Port El-Kantaoui, near Sousse.[38]

Moncef Marzouki refuses to wear a tie, preferring the burnous in homage to Tunisian culture.[39]

Remove ads

Decorations

Tunisian National Honours

:

:

- Grand Collar of the Order of Independence (In his capacity as President of the Tunisian Republic)

- Grand Collar of the Order of the Republic (In his capacity as President of the Tunisian Republic)

- Grand Collar of the National Order of Merit of Tunisia (In his capacity as President of the Tunisian Republic)

Foreign Honors

France : Commander of the Legion of Honour (4 July 2013)

France : Commander of the Legion of Honour (4 July 2013) Morocco : Special Class of the Order of Muhammad (31 May 2014)

Morocco : Special Class of the Order of Muhammad (31 May 2014) Egypt : Grand Cross of the Golden Lion of Alexandria (6 June 2014)

Egypt : Grand Cross of the Golden Lion of Alexandria (6 June 2014) Niger : Grand Cross of the Order of the Niger (23 June 2014)

Niger : Grand Cross of the Order of the Niger (23 June 2014)

Remove ads

Distinctions and awards

- The Maghrebian Medicine Prize (1982)[40]

- Foundation Scanno Literary Prize (1988)[40]

- The Price of the Arab Congress of Medicine (1989)[40]

- Human Rights Watch awards for Freedoms (2001)[40]

- Gold Medal of the Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2012)[41]

- The Chatham House Prize for the year 2012 in London (with Rached Ghannouchi)[42]

- Honorary Degree from University of Tsukuba in 2013[43]

- Al Qods Prize for 2015 in Chicago[44]

- Foundation Ducci Peace Award for 2016 in Rome[45]

- One of the 100 Most Influential Arabs in the World in 2018[46]

Remove ads

Main publications

- Arabes, si vous parliez, ed. Lieu commun, Paris, 1987

- Laisse mon pays se réveiller : vers une quatrième civilisation, ed. Éditions pour le Maghreb arabe, Tunis, 1988

- Le mal arabe, ed. L'Harmattan, Paris, 2004

- Dictateurs en sursis : une voie démocratique pour le monde arabe, ed. de l'Atelier, Paris, 2009

- L'invention d'une démocratie. Les leçons de l'expérience tunisienne, ed. La Découverte, Paris, 2013

- Tunisie, du triomphe au naufrage (with Pierre Piccinin da Prata & Thibaut Werpin), ed. L'Harmattan, Paris, 2013

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads