Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Necropolis of the Rabs

Punic-era cemetery From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Necropolis of the Rabs, also known as the Necropolis of Sainte-Monique, Necropolis of Bordj Djedid, or Djebel Louzir, is a Punic-era cemetery (5th–2nd century BC) located on the archaeological site of Carthage in Tunisia, which was excavated between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The excavation, led by Alfred Louis Delattre, took place under the standard conditions of that period, which impacted the comprehensive understanding of the site. The cemetery, designated for an elite social group within the Punic city, contained marble sarcophagi—now housed in the National Museum of Carthage and the Louvre Museum—along with a diverse collection of funerary items, such as jewelry and ceramics. Salah-Eddine Tlatli described these finds as significant examples of Punic art.

Despite the challenging excavation methods, researchers were able to examine the burial rituals and identify distinct features of the necropolis, distinguishing it from other known Punic burial sites in Carthage across various historical periods.

The archaeological site of the necropolis no longer exists in the early 21st century, as extensive urban development, including the construction of the presidential palace along the coast, has altered the area.

Remove ads

Location and etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Alfred Louis Delattre named the Necropolis of the Rabs in reference to “high sacerdotal dignitaries.”[L 1] He applied this name to a sector of the Sainte-Monique necropolis due to the abundance and quality of the findings, which he believed belonged to “families or funerary colleges.”[M 1] The term "rab," appearing in inscriptions and meaning “chief” in a general sense, reflects the challenges of interpreting the structure and organization of the Punic city, as its usage varies across contexts.[I 1]

The Necropolis of the Rabs is situated in a “rugged and peripheral region” of the Punic city.[H 1] It lies on Sainte-Monique hill,[A 1][H 2] between the Bordj Djedid plateau (translated as “New Fort” in Arabic[K 1]) and the Sainte-Monique convent. Delattre’s excavations took place in the area now located between a modern high school zone and the presidential palace.[K 2] Determining a more exact location is complicated by the limited excavation methodology of the time and the site’s subsequent abandonment.[H 3] Delattre provided no detailed documentation—such as plans, sketches, or precise descriptions—and the necropolis is thought to have originally covered a relatively large area.[L 1]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Ancient history

Necropolises of Carthage

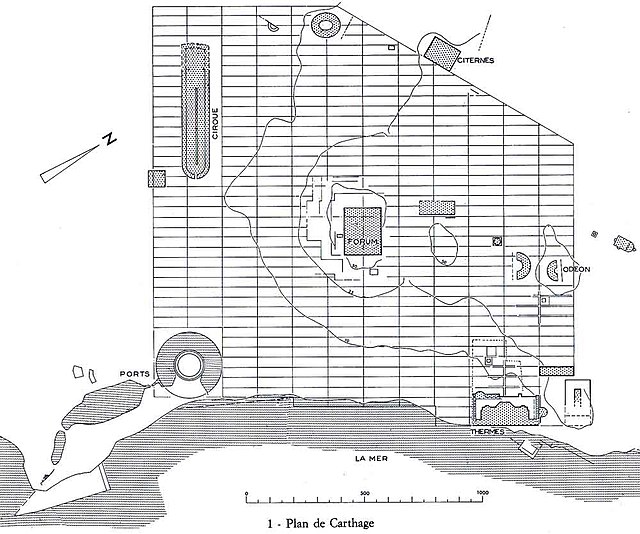

The necropolises of Carthage are estimated to have spanned approximately 60 hectares, while Salah-Eddine Tlatli suggests that the Punic city itself covered more than 300 hectares.[L 2] Hélène Bénichou-Safar, in her book published in 1982 and covering research up to 1977,[K 3] lists over 3,000 tombs excavated over a century on the archaeological site of Carthage.[K 4] M'hamed Hassine Fantar proposes that this figure might be as high as 3,500.[N 1] The excavators of the necropolis of the Rabs explored approximately 1,000 burial chambers at this site alone, which were aligned in rows.[H 2]

History of the so-called "Necropolis of the Rabs"

According to Abdelmajid Ennabli, the Necropolis of the Rabs was in use from the 5th to the 2nd century BC, with peak activity during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.[H 2] He notes that approximately one-third of the tombs date to the 4th century BC, while two-thirds are from the 3rd century BC. Salah-Eddine Tlatli dates the necropolis on Sainte-Monique hill specifically to the 3rd century BC,[L 3] while Colette Picard suggests it was active from the 5th to 4th century BC until the destruction of the Punic city after the Third Punic War in 146 BC.[A 1]

Over time, the necropolises of Carthage evolved, with designated areas allocated for religious colleges, families, or clans, shifting from individual to collective tombs.[K 5] In the 3rd–2nd century BC, the funerary rites used were cremation and inhumation; the deceased were accompanied in their final resting place by gold jewelry, carved ivories, bronze vases, and Sicilian or Etruscan ceramics.[A 2] During the Hellenistic period, from the 4th to the 2nd century BC, cremation predominated, with remains preserved in a limestone box.[Q 1] At that time, “there was a restriction of spaces allotted to the dead.”[Q 2]

Due to the richness of the furnishings found and the architecture of the tombs, it is accepted that the necropolis of the Rabs holds the burials of the Carthaginian high society.[B 1][L 4] Colette Picard posits that it may have been reserved for the city’s priests and priestesses.[A 1] The clergy, drawn from the Punic aristocracy, lacked political authority but included many women among its religious dignitaries.[R 1] Their roles were primarily ceremonial, involving rituals and sacrifices, as evidenced by a rate schedule from the Punic capital discovered in Marseille in the mid-19th century.[R 2]

During the Roman period, under the Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago, the necropolis saw limited use. Alfred Louis Delattre identified a structure in opus reticulatum as a "fanum of Ceres".[H 4] The presence of Punic-era terracotta figurines dedicated to Demeter has led to speculation about a Temple of Demeter existing there in the early 4th century BC, possibly built to address the destruction of a similar temple during the Sicilian Wars. While Stéphane Gsell rejected this idea, findings such as a stuccoed capital (noted by Charles Saumagne) and another architectural element (discovered by a soldier and housed in the Bardo Museum since 1926) have led Gilbert Charles-Picard, Alexandre Lézine, and Naïdé Ferchiou to support the temple hypothesis. Pierre Cintas mentions a temple that existed from the Punic period to the Roman period.[H 5]

The necropolis was later looted for its valuable contents. The sarcophagi of a priest and a priestess were disturbed in antiquity,[T 1] with damage occurring where the marble was thinnest.[U 1]

Organization and architecture of the tombs of the Necropolis of the Rabs

Access to the chambers is either through wells or dromos-type entrances.[O 1] Wells, varying in depth, first appeared in Carthage around the 6th century BC. In the Sainte-Monique necropolis, these wells average 12 meters deep, though some reach depths of up to 27 meters.[M 2] Their depth served multiple purposes: protection against theft, a display of prestige, and possibly religious significance.[K 6] Notches carved into the well walls provided footholds for those ascending or descending.[K 7]

The tombs were dug with varying degrees of care[K 8] and were dug with consideration for the nature of the rock.[M 3] The ground may consist of rock, compacted earth, or sand.[K 9] The access bay to the burial chambers, measuring 1.32 meters by 0.63 meters, may have a console sculpted in the rock.[K 10] The chamber walls were carefully shaped and coated with stucco, occasionally mixed with marble powder.[K 11] Some chambers included decorative stucco elements, and Alfred Louis Delattre noted the presence of cornices at entrances or within the chambers.[N 2] In wealthier tombs, such as that of Yada’milk,[O 2] ceilings may have been lined with wooden paneling made from durable woods sourced from the Kroumirie forests[Q 3] or Cyrenaica.[K 12] Over time, wells could accommodate multiple burial chambers, such as those for couples, typically measuring 2.20 meters by 2.80 meters with a height of 1.90 meters.[L 5]

By the time excavations began, any "external monuments" associated with the necropolis had vanished.[L 1] It is possible that monumental structures,[K 13] such as mausoleums similar to those at Dougga, Sabratha, or Medracen, once existed, as architectural fragments have been uncovered at nearby sites like Ard el-Khéraïb and Byrsa.[N 3] Alfred Louis Delattre described a building covering several funeral wells.[M 4] The city may have had nearby quarries in antiquity; stones could be transported from the quarries of Cape Bon across the Gulf of Tunis, and then shaped on-site.[K 14]

Burial locations were marked by stones or cippi,[L 5] sometimes bearing inscriptions to commemorate the deceased.[M 5] From the 4th century BC, Anthropomorphic stelae, depicting figures in prayerful poses have been identified.[P 1][N 3] Funerary inscriptions, often found in the "aristocratic quarter of the City of the Dead",[K 15] These epitaphs are sometimes engraved on slabs set into the entrances of the tombs,[N 3] were typically engraved on slabs sealing tomb entrances or on rectangular stone tablets described as notable examples of Punic calligraphy.[K 16]

Rediscovery

Early excavation

Between 1878 and 1906, Alfred Louis Delattre excavated several necropolises in Carthage, including the hills of Juno, Byrsa, Douïmès, Bordj Djedid, and Sainte-Monique.[L 6] During the same period, Paul Gauckler conducted parallel excavations on parts of the necropolises, amid a competitive dynamic with the White Fathers.[N 1][Q 4] Archaeological excavations were often "an excuse for social events."[Q 5]

The Necropolis of the Rabs was identified in 1897,[H 2] though earlier reports of tombs in the area had come from "stone hunters."[M 6] Delattre, who discovered the site, excavated it intensively and exclusively between 1898 and 1905 or 1906, working at a rapid pace.[L 7][H 2][H 3] The methods used, while consistent with early 20th-century practices, are considered inadequate by modern standards, and little attention was paid to studying the tomb architecture.[G 1][N 4] Delattre assigned workers to multiple areas within a single sector and provided generalized conclusions for each.[K 17]

The military service made a plan as early as 1898.[K 17] A partial plan was also published in an issue of the journal Cosmos in 1904.[H 2] However, Delattre has been criticized for not creating a comprehensive plan, with some attributing this to his amateur approach. The primary goal of the excavations was to recover funerary artifacts to enhance museum collections, resulting in a significant haul of materials.[H 3][H 6]

Funding for the excavations came from the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Letters.[D 1] Delattre periodically updated the academy on his progress and submitted reports, particularly about the sarcophagi, preserving details that might otherwise have been lost.[M 7] Additional resources were generated through the sale of less significant duplicate items, while many pieces of common pottery were intentionally discarded.[N 3][L 8]

In November 1898,[U 2] Delattre uncovered a painted marble sarcophagus,[C 1] followed by a second one in May 1901.[C 2] On November 25, 1902, at the bottom of a well 12 meters deep,[L 9] he discovered a sarcophagus of a woman hiding her face with a veil,[C 3] which contained two bodies,[C 4] and also that of the priest.[C 5] A tomb containing two sarcophagi was also excavated in November 1902 but had been violated. The lids had been broken by the thieves but without damaging the faces of the figures.[C 6] The male sarcophagus bore traces of a long insignia, which Delattre interpreted as a mark of the individual’s status.[C 7] The female figure in the second sarcophagus appeared elderly, as inferred from her worn teeth.[C 8] Both sarcophagi were photographed and opened on-site before being transported to the Lavigerie Museum on November 27.[U 3][U 1]

On November 4, 1904, a marble sarcophagus of a priest was discovered, accompanied by an ivory box containing bronze objects.[L 1] In total, Alfred Louis Delattre discovered thirteen sarcophagi in the necropolis, four of which contained statues and the others "architectural in style."[T 2]

Legacy, end of excavation, and new studies at the end of the 20th century

Alfred Louis Delattre proposed offering one of the sarcophagi to the Louvre Museum, allowing the institution to select from several pieces.[D 2] The museum’s administration requested two sarcophagi, a proposal accepted by both Delattre and the Tunisian Department of Antiquities and Arts.[D 3] The Louvre Museum received the works in 1906.[T 3] A plaster replica was then deposited at the Carthage Museum.[L 8] At the Lavigerie Museum, the sarcophagi of the priest and priestess were displayed upright in the Punic room, where they attracted significant attention.[U 4]

The discoveries generated widespread interest among specialists. Paul Gauckler, for instance, described the priestess’s sarcophagus as highly significant for the study of ancient art.[L 10] He also noted the similarity between the sarcophagus of the priest and a sarcophagus discovered at the Etruscan archaeological site of Tarquinia as early as 1909 in the Bulletin des antiquaires de France, although the comparative study was later carried out by Jérôme Carcopino.[T 4]

Delattre published his findings in outlets such as the journal Cosmos[H 2]and the Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, as well as in smaller, now-rare publications.[M 8] The terracotta figures were deposited at the Carthage Museum but not cataloged; others joined the Bardo Museum through the Society of Friends of that cultural institution.[H 5]

After the excavations, the site was roughly backfilled and abandoned, eventually fading from clear record.[H 3] Emergency excavations were carried out in 1950 and then in 1951; another excavation in 1967 on the site of a villa led to the excavation of thirteen tombs, whose contents were dated to the 4th–3rd century BCE. Construction work near the presidential palace in Carthage in the 1990s revealed Punic remains, but no excavations followed.[H 7]

Hélène Bénichou-Safar revisited the topic of Carthage’s Punic necropolises in her 1982 publication, Les tombes puniques de Carthage, which compiled the available but scattered documentation.[H 6][O 3] Her work did not include a chronological interpretation.[L 11] Furthermore, excavations carried out on the hill of Byrsa in the 1970s as part of UNESCO’s “Save Carthage” campaign enabled methodical excavations of Punic tombs dating from the 7th–6th centuries BCE.[O 3]

An unknown part of the necropolis was reported in 2015 following preventive excavations prior to the construction of a villa near the presidential palace and Le Corbusier’s Baizeau villa. The remains, although not excavated due to lack of resources, appear to be preserved.[1]

Remove ads

Funerary furniture and various artifacts

Summarize

Perspective

Artifacts with magical or functional purpose

Among the artifacts found during the excavations were both “functional” elements and others intended to provide “magical protection.”[R 3] Objects buried with the deceased served various purposes: identifying them, ensuring their survival or well-being in the afterlife, warding off "evil spirits" through apotropaic items, or acting as offerings.[K 18] Some objects were intended for Chthonic cults and funeral liturgy.[K 19]

The funerary furniture included “six classical items”: a lamp, a patera (shallow libation dish), two jars, and two oenochoae (wine jugs). Food offerings were represented by clay models.[L 12] Female burials contained numerous elements related to beauty: makeup boxes, perfume vials, jewelry, and adornments intended for a “final toilette.”[L 13] Over time, funerary furnishings transitioned from an Egyptian-influenced style to a more Hellenistic one. By the 4th century BCE, burials grew more elaborate, with coins—possibly intended as an obol for Charon—appearing among the grave goods.[L 14] Salah-Eddine Tlatli, following Stéphane Gsell, noted that funerary practices retained a predominantly Eastern character, though they were influenced by temporary Hellenizing trends.[L 15] Tlatli highlighted Carthage’s cosmopolitan nature, shaped by Greek, Egyptian, Phoenician, Etruscan, and Libyan influences.[L 16]

Artifacts were often placed in niches, on sarcophagi, or beside the body,[Q 6][Q 7] including vases, ceramics, statuettes, amulets, jewelry, sarcophagi, ossuaries, and stelae.[H 2] The adornments, described as finely crafted, primarily functioned as protective phylacteries.[K 20]

Ceramics ranged from locally made pieces, sometimes of average quality, to imported ones.[M 9] Jewelry was crafted from precious metals and stones, with glass paste also common. Tombs contained objects made of iron, bronze, and lead.[N 5] Starting in the 4th century BCE, coins linked to Greek Sicily appeared,[M 10] alongside food offerings in pottery and toiletry items.[P 2] Ceramics included baby bottles and askos, as well as lamps of the Greek type.[M 11] Greek pottery was also found, such as dishes decorated with a female figure in profile; these types were locally imitated.[M 12] Statuettes from coroplast workshops also formed part of the standard funerary assemblage.[G 2] Some of this funerary furniture bore inscriptions.[K 21]

Excavations at the Necropolis of the Rabs uncovered amulets crafted from glazed paste or multicolored glass paste, ranging from 5 to 7 centimeters in size and described as "true glass jewels." These were found alongside scarabs reflecting "Egypto-Asiatic" influences.[M 13] The glass paste amulets were worn as pendants[R 4] and were produced locally on cores starting at least from the 4th century BCE.[Q 8] They may depict deities such as Tanit, Ba’al Hammon, or Eshmoun.[Q 9]

The area also yielded Roman-era marble statues representing Ceres and Aesculapius, as well as architectural elements and inscriptions deposited at the National Museum of Carthage by Alfred Louis Delattre.[H 4] In the 1920s, the same area produced a favissa containing Punic-period terracotta statuettes of Demeter and anthropomorphic incense burners.[H 5] The anthropomorphic incense burners are dated to the 3rd century BCE and are associated with the cult of Demeter according to Hélène Bénichou-Safar.[H 5] Statuettes of female musicians were also discovered: players of the tympanon or the lyre.[M 14]

Another terracotta piece depicting a Néréide sur un hippocampe (Nereid on a hippocamp) was also discovered.[H 5] Representations of fruits and animal statuettes were also discovered, symbolizing offerings of actual fruit to deities or the deceased, with evidence suggesting animal sacrifices occurred during funerary rites, possibly tied to symbolic banquets.[R 3][Q 10][M 15]

The tombs yielded objects made of gold, silver, bronze, ivory, and high-quality ceramics.[L 9] However, few gold items were found.[M 16] Some ivory pieces demonstrated skilled craftsmanship.[M 17]

Additional finds included pecten-type seashells, bone or ivory objects such as a makeup spoon, spindles, and spindle whorls.[M 18] Bronze artifacts comprised discs, inscribed razors, Greek-style ewers (though not necessarily Greek-made), and small figurines.[M 19]

Ostrich eggs and protomes were also present, with the eggs—[O 4]sometimes painted red and black using red hematite and silica[Q 11]—regarded as a widespread symbol of life.[K 22]

Inscriptions appeared on vases (many now lost) and on white and black limestone plaques. The Carthage Museum preserves a collection of epitaphs,[N 6] which typically record the deceased’s name, lineage, profession or public role, and, for women, their husband’s name.[N 3][O 5]

Remains of organic material objects

Excavations at the Necropolis of the Rabs revealed traces of organic material objects on stone sarcophagi, including wicker baskets, sandal soles, and vegetal crowns.[M 20] It is suggested that the deceased may have been placed on wooden catafalques, though no direct evidence has been found, making this use speculative.[K 23]

The tombs contained wooden objects, including coffins equipped with bronze handles.[K 24] These could be adorned with ivory decorative elements.[K 25] This practice dates back to the 7th century BCE and became more common at the Sainte-Monique necropolis site. Wood preservation in Carthage is generally poor; however, it has been confirmed that one of the coffins was a reused old chest whose interior was lined with clay.[M 21] Funerary chests made specifically for this purpose did exist, and some examples have been found in various locations along the Sahel and Cape Bon, including Ksour Essef, Thapsus, and Mahdia.[K 26] These chests featured wide feet and hinged lids, reflecting the Carthaginians’ reputation as skilled carpenters.[K 27] Coffins in the Necropolis of the Rabs were assembled with lead pegs and were either painted or sculpted,[K 28] drawing inspiration from techniques used for marble sarcophagi.[G 3] Decomposed coffins left behind traces of "woody dust" and associated fittings in the tombs. In one instance, the colored imprint of an anthropoid coffin was discovered in an otherwise unremarkable tomb, featuring a high-relief statue, possibly of a woman—a find reminiscent of a similar discovery at the Arg el-Ghazouani necropolis near Kerkouane.[K 29] Such coffins are considered to have been reserved for an elite social group.[K 30]

Remove ads

Funerary monuments

Summarize

Perspective

Ossuaries

Over 1,000 ossuary chests have been found in Carthage.[K 31] In the Necropolis of the Rabs, these ossuaries are sometimes crafted from alabaster,[K 32] though they may also be made of cedar or other woods and placed in troughs.[K 31] Their design appears to draw influence from wooden chests, such as those found at Ksour Essef.[K 33]

One notable ossuary, known as the tomb of Ba’alshilek the rab, features a high-relief figure on its lid, identified as a religious dignitary.[M 1][K 34] Dated to the 3rd century BCE and housed at the Carthage Museum, this ossuary depicts a bearded, mustached man wearing an epitoge—described as a “priestly insignia”—with his right hand raised in a prayer gesture. Measuring 0.28 meters by 0.48 meters with a thickness of 0.21 meters,[R 5] it is considered an imitation of the larger priest’s sarcophagus, sharing similar posture and attire.[E 1][S 1] This artifact was discovered in 1898.[T 5][C 9] Such attributes in male figures on sarcophagi and ossuaries are typical of Carthaginian art from the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE.[T 6] Another limestone ossuary features a priest in low relief, seated on two cushions.[R 6]

Sarcophagi

Punic sculpture is not well-documented, with most known examples coming from funerary contexts.[R 7]

Excavations at the Rabs necropolis have yielded around fifteen sarcophagi of Greek influence, dated to the 4th–3rd century BCE, which show parallels with Southern Italy and Athens.[B 1] The site also revealed elements influenced by Egypt, being in the form of mummies.[P 3] Hélène Bénichou-Safar dates the sarcophagi from the end of the 4th to the mid-3rd century BCE.[K 35]

The sarcophagi are made of monolithic limestone.[L 5] These sarcophagi stand in contrast with traditional Carthaginian funerary art, which was executed in local limestone and usually devoid of aesthetic considerations.[Q 12] They were crafted above ground and lowered into burial shafts using ropes.[K 36]

The sarcophagi discovered could have been made of wood, sandstone, stone, and marble.[H 2] Some wooden sarcophagi are fragmentary, with only traces remaining.[N 5] Excavations uncovered components, fragments, metal fittings, and handles.[P 2] Sarcophagi made of shelly sandstone are of an earlier type.[M 7] One stone sarcophagus features on its lid a figure of a priest with his head resting on a bolster.[M 1]

Sarcophagi in the form of a Greek emple

Some sarcophagi show Greek influence with a rectangular chest and a lid shaped like a roof.[P 3] They resemble Greek temples, with acroteria[C 10] and pediments once decorated with paintings now faded. They may have been made in Carthage by Greek immigrants.[A 3][K 37] While their Greek origin is likely, they were designed for Punic patrons.[E 2] The sarcophagus, chest and lid, forms “the image of the dwelling of the dead.”[C 10]

Some sarcophagi were made of white marble or limestone, the largest measuring 2.75 meters by 1 meter and weighing perhaps 5 tons. They may have been adorned with paintings or sculptures, and the pediments might have been decorated with moldings.[K 36] Identified decorative themes include a winged spirit, Scylla surrounded by her dogs, and opposing sphinxes.[K 37]

Sarcophagi with sculpted lids

General overview

The use of sarcophagi by the Phoenicians is very ancient and inspired by Ancient Egypt.[F 1][K 38] The sarcophagus served to protect the deceased, complementing the shroud and coffin, following the Egyptian practice of multiple wrappings for the dead.[K 39]

Anthropoid sarcophagi are the “most original and most sumptuous” category,[K 37] and the collection includes four pieces with sculpted[B 1] and painted lids, in limestone or marble.[A 1] The paintings on the sarcophagi disappeared after their rediscovery due to exposure to air,[M 22] and only traces of color remain today. These works are notable for both their size and the quality of the sculptures.[M 1] One of the pieces had its lid and chest sealed with iron and lead. The lid either had handles or was fitted with cords.[K 40]

The sarcophagi feature high relief carvings[G 3] and depict “reclining statues of figures shown standing on a stone base fixed in a hieratic pose.”[K 41] The deceased is depicted standing but in a horizontal position.[F 2][C 11] The figures have been interpreted as priests or priestesses based on their clothing.[K 40] Their gestures are, for the women, “conventional,” and for the male figures, gestures of prayer[K 40] or devotion according to Serge Lancel.[Q 13]

Anthropoid sarcophagi of Carthage

Among the four sarcophagi, two depict male figures and two depict female figures. A burial chamber containing a priest’s sarcophagus also housed the sarcophagus known as the Winged Priestess.[E 3] This same tomb included an additional funerary chamber where the remains of six coffins and six stone ossuaries were discovered, one of which had a marble lid described as improvised.[U 5]

Two sarcophagi depict a male figure interpreted as a priest dressed in a tunic, with his right hand raised in adoration[Q 13] or prayer and his left hand holding a censer.[A 1][P 4] The gesture of prayer is common in Carthaginian civilization.[G 4] The priest’s facial expression is described as calm,[E 2] “serious and solemn,”[C 5] conveyed through full-round sculpture and traces of paint that lend the figure a lifelike quality.[E 2][C 9] The man wears a robe and a shoulder mantle (epitoge).[P 4] The priest’s sarcophagus was sealed with iron and lead. The deceased had a rod beside him, possibly indicating a badge of office.[U 6] The sarcophagus preserved in Carthage is in high relief and represents a bearded figure dressed in a long tunic. The work is dated to the end of the 4th century BCE and the beginning of the 3rd century BCE.[E 2] The sarcophagus preserved in the Louvre measures 1.80 meters.[T 3]

The female sarcophagus, known as the Lady’s Sarcophagus,[T 2] held at the Louvre Museum, features "a stele with a flat background.”[S 2] The work is inspired by Greek art.[T 2] This full-round sarcophagus[P 4] shows a priestess veiling herself, in a style related to Greek works of the 4th century BCE.[D 1] The “modest and graceful posture” of the young woman is highlighted by Antoine Héron de Villefosse, with the figure rendered lifelike and finely crafted.[C 12]

The sarcophagus known as the Winged Priestess Sarcophagus, crafted in white marble,[S 2] is “the most remarkable” of the series.[P 3] It portrays a woman with bird-like wings, possibly symbolizing the goddess Tanit. One hand holds an inverted dove, likely a mourning symbol, while the other holds a perfume vase or a box.[A 1][P 4] The figure is veiled, exuding a sense of majesty.[C 7][P 3] She wears an Egyptian hairstyle, and the wings seem to recall attributes of Isis or Nephthys.[2] A falcon-headed veil covers her.[R 7] The wings cross over her knees,[P 5] and the lower part of the body “almost resembles a fish tail.”[U 7] This full-round sculpture, likely depicting a priestly figure, features a head of understated beauty.[P 3] Originally adorned with bright colors, the sarcophagus measures 0.93 meters in height, 1.93 meters in length, and 0.67 meters in width.[P 4][R 7] The lid was broken in antiquity to allow access.[S 2] The effigy lies on a gabled roof of Greek type and is the work with the most pronounced orientalizing[T 2] or Egyptianizing traits among the series of sarcophagi.[S 2] The woman buried in the sarcophagus was elderly at her death and measured between 1.55 and 1.56 meters.[U 8] Twenty-one bronze coins were found with her by the excavator.[U 6]

The sarcophagus of the priestess displays a blend of influences, with Greek elements discernible alongside Egyptian ones.[C 13] Hédi Dridi describes it as “a true manifesto of Punic eclecticism", reflecting a fusion of Oriental, Egyptian, and Greek styles.[R 8][B 1]

Initially, these sarcophagi were thought to be Greek creations.[E 2] Serge Lancel suggests that while Greek artisans could have been involved, the works might also have been crafted by Carthaginians.[T 7] Hédi Slim considers the Punic character particularly evident in the priestess’s clothing. The male figures find parallels in the representations seen on stelae.[R 8] Consequently, the sarcophagi are regarded as local products enriched by diverse influences,[S 2] challenging earlier assertions by Stéphane Gsell or Jérôme Carcopino, who attributed them solely to Greek origins.[Q 14] The design appears to stem from an Oriental prototype, adapted in a Greek style during the Hellenistic period,[K 42] making these pieces examples of Punic art from that era.[R 8]

The figures have been interpreted as idealized portraits or as protective deities.[K 40] Similar sarcophagi, crafted in wood, have been uncovered at Carthage and Kerkouane, and may have inspired Etruscan works.[F 2]

- Detail of the wooden sarcophagus of Kerkouane, preserved in the site museum.

- Sarcophagus of the priestess preserved in the Carthage museum, marble, 4th or 3rd century BC, 76 × 197 × 68 cm.[2]

- Detail of the priestess' sarcophagus.

- Sarcophagus of the priest kept in the Carthage Museum, white marble, formerly painted, 4th century BC, 72 × 193 × 65 cm.[J 1]

Analogy with the Tarquinia sarcophagus

One of the priest sarcophagi has a close counterpart housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Tarquinia in Etruria, prompting questions about its origin and the workshops involved.[K 42] According to C. Mahy, the works show differences in detail.[T 1] This piece, in Parian marble, was discovered in 1876 in the Monterozzi necropolis in a family tomb containing fifteen sarcophagi. It was the first in the series to be placed in the hypogeum.[T 8] The name of the sarcophagus’s owner, Laris Partiunus, appears in three locations and is “written from right to left.”[T 9] Archaeologists have traced the genealogy of the gens Part(i)unus, a prominent family among the city’s elite, spanning five generations.[T 10]

The figure depicted is not identified as a priest or magistrate. The sarcophagus is dated either to the second half of the 4th century BCE, a period marked by notable interactions between Carthaginians and Etruscans, or to the late 4th century through the first half of the 3rd century BCE. During this time, treaties between the two groups encompassed political, economic, and military dimensions.[T 11] The work is comparable to known portraits from Greece dated to the mid-4th century BCE.[T 12] This mode of representation developed in the 4th–3rd centuries BCE.[T 13]

Unlike the Carthaginian sarcophagi,[T 14] the Tarquinia sarcophagus features a chest adorned with frescoes depicting mythological scenes. One scene has been interpreted either as an episode from the Iliad, showing Achilles slaying Trojan prisoners, or as a representation of Alexander the Great’s triumphs over the Persians.[T 15] The opposite side portrays an Amazonomachy, depicting Greeks defeated in battle,[T 16] while one short side includes an Amazon figure.[T 17] The paintings were done by Etruscans based on Greek models like those in the François Tomb.[T 18]

The lid depicts “an upright statue later laid down by the sculptor” on a gabled roof with acroteria.[T 19] The figure, bearded and curly-haired, has an “idealized” face, his right hand raised, and the left holding a pyxis. He wears a tunic, an epitoge, and sandals. The face was originally polychrome.[T 20]

A Sicilian origin was once suggested for both the Tarquinia and Carthaginian sarcophagi, but C. Mahy deems this hypothesis unlikely.[T 21] The Etruscan origin of the sarcophagus is likely.[T 16] Even though Greek artisans were present in the Punic world, the underlying belief behind the Carthaginian sarcophagi is Punic.[T 22]

The style of representation may have been introduced by Etruscans who traveled to Carthage.[T 13] Archaeological evidence confirms the presence of Etruscans in Carthage’s Bordj Djedid necropolis, the city’s wealthiest burial site at the time, by the late 4th century BCE.[T 23] Laris Partunus, the sarcophagus’s owner, may have resided in Carthage and could have been involved in the conflict against Agathocles, where Etruscans played a role.[T 15] He may have returned to his homeland with the sarcophagus or had it shipped later.[T 24] The piece is dated to the end of the 4th century BCE.[T 14]

The sarcophagus from Carthage and the one in Tarquinia share a notable similarity.[T 1] C. Mahy suggests that, based on comparisons with other Carthaginian finds, they likely belong to the same group of sculpted monuments. The Tarquinia sarcophagus may have been crafted in Carthage by Greek artisans, possibly for a Carthaginian or Etruscan client in Africa, or for an Etruscan with strong ties to the Punic capital.[T 25] The frescoes on the chest may have been added after importation, and the repeatedly inscribed name may correspond to the time needed to complete the paintings.[T 26]

- View of the upper part of the sarcophagus, seen from the left side. The man has his right hand raised.

- General view of the upper part of the sarcophagus.

- Close-up of the figure's face.

- View of one side of the sarcophagus with paintings and the gabled roof.

- View of a long side of the sarcophagus with the painting of either Alexander or the Greeks defeated in battle.

Remove ads

Interpretation

Summarize

Perspective

The place of death and Necropolises in Carthaginian civilization

Carthaginian civilization placed great importance on the "eternal dwelling," known as BT'LMQ.[Q 16] Funerary pits, or shafts, were designed to protect against looters. Depending on their social status, the deceased were interred in wooden coffins, sarcophagi, or directly within the funerary chamber.[L 12][N 5] The care given to the dead is a sign of "a deep spiritual life."[L 16] Tombs were regarded as places of peace, rest, or eternal abode for the dead.[O 4] Necropolises were known as shad elonim, meaning "field of the gods," with individual tombs called qabr.[G 5]

Funerary furnishings were intended to remind the deceased of their life or to protect them from "evil forces." There may have been a belief in "a certain form of survival" after death.[O 6] The tomb was therefore considered "a replica of the dwelling of the living."[M 23]

Funerary architecture emerged from the natural rock, characterized by simplicity. Most funerary chambers lacked decoration, reflecting a preference for mystical austerity,[L 12] with the exception of a tomb at Djebel Mlezza near Kerkouane.[K 14] In this tomb, the soul, termed rouah—comparable to the Latin animus—was depicted as a bird. The tomb’s painted decoration features a rooster moving from a mausoleum toward a city, which M’hamed Hassine Fantar interprets as symbolizing the soul’s journey to the "city of the dead" or a celestial realm.[O 6][G 2][R 9] A sacrificial altar with a fire is located near a mausoleum.[Q 2] The rooster is associated with the mausoleum in Africa, as recalled by the inscription on the Mausoleum of the Flavii in Kasserine; this association may be Libyan or the result of a cultural blending with the Punic people.[Q 17]

The rituals reflect the "mixed nature of the Carthaginian population," composed of Easterners and a Libyan population. The presence of red ochre on the bodies, reminiscent of blood, is related to indigenous rites.[R 3] The color red had a "strong revivifying power," according to Hélène Bénichou-Safar.[K 43]

The deceased, referred to as rephaïm,[Q 16] may have been subjects of religious reverence. Protected by deities, some sites suggest the presence of ritual funerary enclosures. Carthaginians likely held beliefs in the soul’s survival and exhibited a deep concern about the uncertainties of death, accompanied by superstitious tendencies.[K 44][K 45]

Distinctive features of the necropolis

Necropolises in Carthage, like those in many ancient Greco-Roman Mediterranean cities, were situated outside the city boundaries. At the Carthage site, pinpointing the exact layout of the city wall remains challenging, though the necropolis hills were strategically incorporated within the fortified area.[N 7] The necropolises known in the early 21st century form a "semicircle around the coastal plain."[O 3]

The Carthage site contains other necropolises, some of which are near the Rabs Necropolis, such as the one known as Ard el-Khéraïb, also located on the hill of Bordj Djedid.[H 6][H 8]

The Rabs Necropolis contains more shaft tombs.[H 9] It is also marked by a "Hellenistic influence," unlike two other necropolises, Dermech and Douïmès, which are marked instead by "an Egyptian and Asiatic influence."[H 9]

The objects found at these sites show Egyptian influence, with amulets representing Anubis, Bes, Osiris, and similar figures.[L 4] The necropolises of Ard el-Mourali and Ard el-Khéraïb display transitional characteristics.[M 24] The Rabs Necropolis is also the one that yielded the most epitaphs from the Carthage site.[M 5]

According to Paul Gauckler, Punic religion underwent profound changes with the introduction of the cult of Demeter and Persephone at the beginning of the 4th century BCE, which had consequences for the funerary rites, as evidenced by discoveries in the Rabs Necropolis. Salah-Eddine Tlatli, however, highlights a persistent adherence to Eastern traditions until the Punic city’s destruction, noting that Hellenistic trends left only a superficial imprint.[L 15] Pierre Cintas describes a "Hellenized world" overlying a fundamentally Punic cultural base, attributing this Hellenization to the adoption of Greek cults and interactions with Greek Sicily.[M 25] These religious borrowings were meant to better protect the deceased.[M 26]

Testimony of the apogee before the end of the Punic city

The necropolises that follow that of the Rabs, particularly on the Odeon Hill, are significantly less elaborate and lack jewelry. Salah-Eddine Tlatli describes Carthage during this period as "a ruined, anxious city, forced to deprive the dead of the final honors of the living,"[L 17] attributing this to the severe difficulties brought by the Punic wars.

Funerary traditions continued, indicating "the stability of the ethnic base and the persistence of undergone influences," even though some were no longer understood, demonstrating gestures performed "automatically."[K 46] These traditions are a sign of conservatism in the Punic city. Cremation developed significantly due to the process of Hellenization, especially through relations with Greek Sicily and later with Alexandria.[K 47]

Carthaginian funerary sculpture, including sarcophagi, constitutes the only known works of Punic statuary, as most were destroyed by looting of the archaeological site or by the removal of artworks by Scipio Aemilianus.[Q 18] The garments of the priestess—or perhaps a representation of Tanit—reflect "a unique syncretism" between Egyptianizing and Hellenistic elements.[Q 19]

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads