Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

History of Newark, New Jersey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Newark has long been the largest city in New Jersey. Founded in 1666, it greatly expanded during the Industrial Revolution, becoming the commercial and cultural hub of the region. Its population grew with various waves of migration in the mid-19th century, peaking in 1950. It suffered greatly during the era of urban decline and suburbanization in the late 20th century. Since the millennium it has benefited from interest and re-investment in America's cities, recording population growth in the 2010 and 2020 censuses.

Remove ads

Founding and 18th century

Summarize

Perspective

Newark was founded in 1666 by Connecticut Puritans led by Robert Treat from the New Haven Colony to avoid losing political power to others not of their own church after the union of the Connecticut and New Haven colonies.[1][2][3] The site for Newark was chosen because the Purtians wanted an isolated location that was remote and protected from outside influence.[4] It was the third settlement founded in New Jersey, after Bergen, New Netherland (later dissolved into Hudson County, then incorporated into Jersey City) and Elizabethtown (modern-day Elizabeth).[5]

They sought to establish a theocratic colony with strict church rules similar to the one they had established in Milford, Connecticut. Treat wanted to name the community "Milford." Another settler, Abraham Pierson, had previously been a preacher in England's Newark-on-Trent, and adopted the name;[6] he is also quoted as saying that the community reflecting the new task at hand should be named "New Ark" for "New Ark of the Covenant." The name was shortened to Newark.[7][8] References to the name "New Ark" are found in preserved letters written by historical figures such as James McHenry dated as late as 1787.[9]

Treat and the party bought the property on the Passaic River from the Hackensack Indians by exchanging gunpowder, 100 bars of lead, 20 axes, 20 coats, guns, pistols, swords, kettles, blankets, knives, beer, and ten pairs of breeches.[10]

Following the Treaty of Westminster, New Jersey split into East Jersey and West Jersey. From 1674 to 1702, Newark was part of East Jersey and became a town in Essex County on March 7, 1683, one of the four newly independent counties in East Jersey. On October 31, 1693, Newark was organized as a New Jersey township based on the Newark Tract, which was first purchased on July 11, 1667. In 1702, New Jersey was reunified and became a royal colony.[11]

Newark was granted a royal charter on April 27, 1713. It was incorporated on February 21, 1798, by the New Jersey Legislature's Township Act of 1798, as one of New Jersey's initial group of 104 townships. During its time as a township, portions were taken to form Springfield Township (April 14, 1794), Caldwell Township (February 16, 1798; now known as Fairfield Township), Orange Township (November 27, 1806), Bloomfield Township (March 23, 1812) and Clinton Township (April 14, 1834, remainder reabsorbed by Newark on March 5, 1902).[11]

The first four settlers built houses at what is now the intersection of Broad Street and Market Street, also known as "Four Corners."[12]

The total control of the community by the Puritan Church continued until 1733 when Josiah Ogden harvested wheat on a Sunday following a lengthy rainstorm and was disciplined by the Church for Sabbath breaking.[13] He left the church and corresponded with Episcopalian missionaries, who arrived to build a church in 1746 and broke up the Puritan theocracy.[14]

It took 70 years to eliminate the last vestiges of theocracy from Newark, when the right to hold office was finally granted to non-Protestants.[15]

First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916) and Indian and the Puritan (1916) are two of four public art works created by Gutzon Borglum that are located in Newark commemorating the city's founding.[16][17][18]

American Revolution

During Washington's retreat across New Jersey, General Washington and the Continental Army made camp at Military Park in Newark and General Washington made his headquarters at Eagle Tavern on Broad Street from November 22 to 28, 1776.[19][20][4]

On the night of January 25, 1780, British troops attacking from Manhattan, via a frozen Hudson River, raided Newark and burned down Newark Academy, which was being used as barracks to house Continental Army soldiers, ransacked neighboring homes and killed several people. Over thirty people were captured and taken prisoner back to Manhattan by the British.[21]

Remove ads

Industrial era to 1900

Summarize

Perspective

Newark's rapid growth began in the early 19th century, much of it due to a Massachusetts transplant named Seth Boyden. Boyden came to Newark in 1815 and immediately began a torrent of improvements to leather manufacture, culminating in the process for making patent leather. Boyden's genius led to Newark's manufacturing nearly 90% of the nation's leather by 1870, bringing in $8.6 million in revenue to the city in that year alone. In 1824, Boyden, bored with leather, found a way to produce malleable iron. Newark also prospered by the construction of the Morris Canal in 1831. The canal connected Newark with the New Jersey hinterland, at that time a major iron and farm area.[22]

By 1826, Newark's population stood at 8,017, ten times the 1776 number.[23] Railroads arrived in 1834 and 1835 along with a flourishing shipping business and Newark became the area's industrial center. On April 11, 1836, Newark was reincorporated as a city replacing Newark Township based on the results of a referendum passed on March 18, 1836.[11]

The middle 19th century saw continued growth and diversification of Newark's industrial base. The first commercially successful plastic — Celluloid — was produced in a factory on Mechanic Street by John Wesley Hyatt. Hyatt's Celluloid found its way into Newark-made carriages, billiard balls, and dentures. Dr. Edward Weston perfected a process for zinc electroplating, as well as a superior arc lamp at the Weston Electric Light Company in Newark. As a result, the city's Military Park had the first public electric lamps anywhere in the United States. Before moving to Menlo Park in 1876, Thomas Edison made Newark his home in the early 1870s where he developed the Universal Stock Ticker which was one of the earliest practical stock ticker machines.[24]

In the late 19th century, Newark's industry was further developed, especially through the efforts of such men as J. W. Hyatt. From the mid-century on, numerous Irish and German immigrants moved to the city. The Germans were primarily refugees from the revolutions of 1848,[25] and, as other groups later did, established their own ethnic enterprises, such as newspapers and breweries. However, tensions existed between the "native stock" and the newer groups.

In the middle 19th century, Newark added insurance to its repertoire of businesses; Mutual Benefit was founded in the city in 1845 and Prudential in 1873. Prudential, or "the Pru" as generations knew it, was founded by another transplanted New Englander, John Fairfield Dryden. He found a niche catering to the middle and lower classes. In the late 1880s, companies based in Newark sold more insurance than those in any city except Hartford, Connecticut.[26]

By 1860, Newark had grown to be the eleventh largest city in the United States and the country's largest industrial-based city.[4]

In 1867, the designers of New York's Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, had been asked by the Newark Park Commission, created by the New Jersey State Legislature, for their recommendations on sites in Newark to create a "central park" for the city. In October 1867, they presented a report on a site adjacent to Old Blue Jay Swamp as the best location for the park.[27] However, the state legislature denied the $1 million required to acquire and improve the land. The idea for a park was scuttled until Essex County spearheaded the project 28 years later. By the time Branch Brook Park was built in 1895 as the first county park in the United States, only a third of the original 700 acres (280 ha) that were envisioned were available for twice the cost. Prior to Branch Brook Park, almost no land in Newark was preserved for park space with the exception of the Downtown colonial era commons at Military Park, Washington Park and Lincoln Park. Even in these limited park spaces, Newark didn't provide basic amenities such as benches or water fountains that were often found in parks in other cities.[4][28]

Sanitary conditions were bad throughout urban America in the 19th century, but Newark had an especially bad reputation. The city lacked the bold leadership and imagination seen in other cities in addressing urban problems. For most of the 19th century, city leaders allowed the business elite and private interests to formulate civic policy and run public agencies in pursuit of unfettered growth and industrialization. This led to multiple issues such as a lack of any urban planning and park construction, the accumulation of human and horse waste build up on unpaved city streets, the over reliance on cesspools and wells followed by the city's inadequate, poorly designed and haphazardly constructed sewage system, and the unreliability and dubious quality of its water supply. Newark did not have a proper public medical center or hospital until 1882, relying on neighboring cities and private medical facilities for emergency care.[29] By 1890, Newark had the highest rate of death for cities of over 100,000 people, led the nation in deaths by scarlet fever and had the highest rate of infant mortality in the United States. Newark also ranked in the top ten of cities for diseases such as croup, diphtheria, malaria, tuberculosis and typhoid fever. As a result, that year the United States Census Bureau declared Newark "the nation's unhealthiest city."[30][28]

In 1889, to finally address the public health crisis, mayor Joseph E. Haynes (1884–1894) contracted with the East Jersey Water Company for $6 million to construct three reservoirs and several aqueducts on the Pequannock River capable of delivering 50 million gallons of water daily to the city. The reservoir system opened in May 1892 removing the city's water supply from the polluted Passaic River which led to a 70% decline in typhoid deaths.[31][32]

In 1880, Newark's population stood at 136,500 in 1890 at 181,830; in 1900 at 246,070; and in 1910 at 347,000, a jump of 200,000 in three decades.[33] As Newark's population approached a half million in the 1920s, the city's potential seemed limitless. It was said with great hubris in 1927: "Great is Newark's vitality. It is the red blood in its veins – this basic strength that is going to carry it over whatever hurdles it may encounter, enable it to recover from whatever losses it may suffer and battle its way to still higher achievement industrially and financially, making it eventually perhaps the greatest industrial center in the world."[34]

Remove ads

1900-1945

Summarize

Perspective

Newark was bustling in its heydays of the early-to-mid-20th century with commerce, new construction and innovation. The Newark Public Library, founded in 1887, opened its main branch of the library in 1901.[35] Newark City Hall and the Essex County Courthouse opened as two civic landmarks in 1902 and 1904 respectively. Broad and Market Streets served as a center of retail commerce for the region, anchored by four flourishing department stores: Hahne & Company, Bambergers and Company, S. Klein and Kresge-Newark. "Broad Street today is the Mecca of visitors as it has been through all its long history," Newark merchants boasted, "they come in hundreds of thousands now when once they came in hundreds."[36] Newark before the 20th century was described by visitors as "a prosperous but uninteresting city" because "New York is too conveniently near" providing little "encouragement from artists and actors."[4] That sentiment changed after the turn of the century to the point that by 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters, 46 movie theaters, and an active nightlife. Oct. 23, 1935, mobster Dutch Schultz was killed at the Palace Chop House in one of the most notorious Mafia hits in American history.[37]

By some measures, the intersection of Broad and Market Streets — known as the "Four Corners" — was the busiest intersection in the United States. In 1915, Public Service counted over 280,000 pedestrian crossings in one 13-hour period. Eleven years later, on October 26, 1926, a State Motor Vehicle Department check at the Four Corners counted 2,644 trolleys, 4,098 buses, 2,657 taxis, 3,474 commercial vehicles, and 23,571 automobiles. In 1932, the Pulaski Skyway opened providing motorists a direct link with Jersey City and Manhattan via the Holland Tunnel. By 1935, traffic in Newark had become so heavy that the city decided to convert the bed of the old Morris Canal into the Newark City Subway line. The subway–surface line was capped by a new road for traffic, Raymond Boulevard, and designed to reduce congestion in the Downtown area by directing the trolley lines into the subway via several street ramps that connected them to the newly re-built Newark Penn Station.

Newark Airport opened in 1928 as the first major commercial airport to serve the New York metropolitan area, the first commercial airport in the United States and the first with a paved airstrip. Innovations continued at the airport when it became the site of the nation's first air traffic control tower and weather station in 1930 and the first passenger terminal in 1934. Amelia Earhart would dedicate the Newark Metropolitan Airport Building in 1935. The airport was the first in the United States to allow nighttime operations when it installed runway lights in 1952.[38]

New skyscrapers were being built every year with the two tallest in the city being the Art Deco National Newark Building built in 1931 and the Lefcourt-Newark Building built in 1930. The National Newark Building was the tallest in the state until 1989. In 1948, just after World War II, Newark hit its peak population of just under 450,000. The population also grew as immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe settled there. Newark was the center of distinctive neighborhoods, including a large Eastern European Jewish community concentrated along Prince Street.[39]

Remove ads

Post-World War II era

Summarize

Perspective

Problems existed underneath the industrial hum. In 1930, a city commissioner told the Optimists, a local booster club:

Newark is not like the city of old. The old, quiet residential community is a thing of the past, and in its place has come a city teeming with activity. With the change has come something unfortunate—the large number of outstanding citizens who used to live within the community's boundaries has dwindled. Many of them have moved to the suburbs and their home interests are there.[40]

While many observers attributed Newark's decline to post-World War II phenomena, others point to an earlier decline in the city budget as an indicator of problems. It fell from $58 million in 1938 to only $45 million in 1944. This was a slow recovery from the Great Depression. The buildup to World War II was causing an increase in the nation's economy. The city increased its tax rate from $4.61 to $5.30.

Some attribute Newark's downfall to its propensity for building large housing projects. Newark's housing had long been a matter of concern, as much of it was older. A 1944 city-commissioned study showed that 31% of all Newark dwelling units were below standards of health, and only 17% of Newark's units were owner-occupied. Vast sections of Newark consisted of wooden tenements, and at least 5,000 units failed to meet thresholds of being a decent place to live. Bad housing was the cause of demands that government intervene in the housing market to improve conditions.[41]

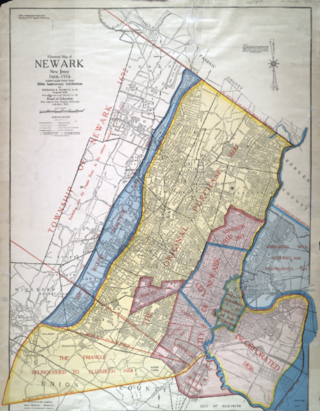

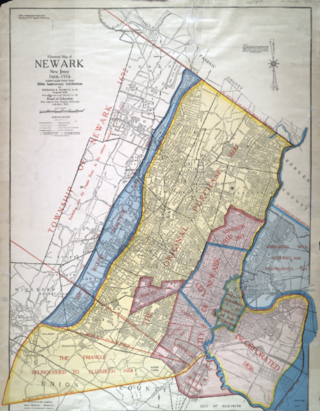

Historian Kenneth T. Jackson and others theorized that Newark, with a poor center surrounded by middle-class outlying areas, only did well when it was able to annex middle-class suburbs. When municipal annexation broke down, urban problems were exacerbated as the middle-class ring became divorced from the poor center. In 1900, mayor James M. Seymour (1896–1903), while arguing for the creation of "Greater Newark", confidently speculated, "East Orange, Vailsburg, Harrison, Kearny, and Belleville would be desirable acquisitions. By an exercise of discretion we can enlarge the city from decade to decade without unnecessarily taxing the property within our limits, which has already paid the cost of public improvements." Only Vailsburg would ever be added.[40]

Although numerous problems predated World War II, Newark was more hamstrung by a number of trends in the post-WWII era. The Federal Housing Administration redlined virtually all of Newark, preferring to back up mortgages in the white suburbs. This made it impossible for people to get mortgages for purchase or loans for improvements. Manufacturers set up in lower wage environments outside the city and received larger tax deductions for building new factories in outlying areas than for rehabilitating old factories in the city. The federal tax structure essentially subsidized such inequities.

Billed as transportation improvements, construction of new highways: Interstate 280, the New Jersey Turnpike, Interstate 78 and the Garden State Parkway harmed Newark. They directly hurt the city by dividing the fabric of neighborhoods and displacing many residents through property acquisition and demolition. The highways indirectly hurt the city because the new infrastructure made it easier for middle-class workers to live in the suburbs and commute into the city.

Despite its problems, Newark tried to remain vital in the postwar era. The city successfully persuaded Prudential and Mutual Benefit to stay and build new offices. Rutgers University-Newark and New Jersey Institute of Technology expanded their Newark presences, with the former building a brand-new campus on a 23-acre (9 hectare) urban renewal site. Seton Hall University School of Law relocated from Jersey City to Newark in 1951 and graduated its first class in 1954.[42] During the postwar era, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey made Port Newark the first container port in the nation and took over operations at Newark Liberty International Airport, now the twelfth busiest airport in the United States.

The city made serious mistakes with public housing and urban renewal, although these were not the sole causes of Newark's tragedy. Across several administrations, the city leaders of Newark considered the federal government's offer to pay for 100% of the costs of housing projects as a blessing. The decline in industrial jobs meant that more poor people needed housing, whereas in prewar years, public housing was for working-class families. While other cities were skeptical about putting so many poor families together and were cautious in building housing projects, Newark zealously pursued federal funds. Eventually, Newark had a higher percentage of its residents in public housing than any other American city.

The largely Italian-American First Ward, once known as Newark's Little Italy, was one of the hardest hit by urban renewal. Beginning in 1953, a 46 acre (19 ha) housing tract, labeled a slum because it had dense older housing, was torn down for multi-story, multi-racial Le Corbusier-style public housing high rises, named the Christopher Columbus Homes. The tract had contained 8th Avenue, the commercial heart of the neighborhood. Fifteen small-scale blocks were combined into three "superblocks." The area experienced one of the highest crime rates in the city during the 1970s and suffered major destruction from arson fires. The Columbus Homes, never in harmony with the rest of the neighborhood, were vacated and abandoned in the 1980s. They were finally torn down in 1996.[43][44] The Pavilion and Colonnade Apartments, built in 1960 for middle-class families, remain as New Jersey's first urban renewal project and one of the first in the nation.

Between 1949 and 1967, at least 10,000 historic buildings across 2,500 acres (1,011 ha) were demolished displacing 50,000 residents, 65% of whom were black and Hispanic. Newark spent more on urban renewal per capita than any of the nation’s thirty major cities.[45]

From 1950 to 1960, while Newark's overall population dropped from 438,000 to 408,000, it gained 65,000 non-whites. By 1966, Newark had a black majority, a faster turnover than most other northern cities had experienced. Evaluating the riots of 1967, Newark educator Nathan Wright Jr. said, "No typical American city has as yet experienced such a precipitous change from a white to a black majority." The misfortune of the Great Migration and Puerto Rican migration was that Southern blacks and Puerto Ricans were moving to Newark to be industrial workers just as the industrial jobs were decreasing sharply. Many suffered the culture shock of leaving a rural area for an urban industrial job base and environment. The latest migrants to Newark left poverty in the South to find poverty in the North.

During the 1950s alone, Newark's white population decreased by more than 25 percent, from 363,000 to 266,000. From 1960 to 1967, its white population fell further to 46,000. Although immigration of new ethnic groups combined with white flight markedly affected the demographics of Newark, the racial composition of city workers did not change as rapidly. In addition, the political and economic power in the city remained based on the white population.

In 1966, without consulting any residents of the neighborhood to be affected, mayor Hugh J. Addonizio (1962–1970) offered to condemn and raze 150 acres (61 hectares) of a densely populated black neighborhood in the central ward for the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) to move the school from Jersey City to Newark. UMDNJ had wanted to settle in nearby suburban Madison.

In response to the Addonizio administration's lack of school construction, ability to reduce crime, or address the city's concerning property tax situation, former mayor Leo P. Carlin (1953–1962) prophetically warned, "Newark is a city in trouble, a city that is running out of time."

In the spring of 1967, the Addonizio administration applied for federal urban renewal funding through the Model Cities Program. The application highlighted the city's unstable, poor population and its highest in the nation per-capita tax rate. In the application, the administration stated:

The most uncommon characteristic of the city may well be the extent and severity of its problems. There is no major city in the nation where these common urban problems range so widely and cut so deeply...Boasting about progress is unthinkable. Times are too volatile, and to ignore that fact in a welter of self-praise would be fatal.[4]

In 1967, out of a police force of 1,400, only 150 members were black, mostly in subordinate positions. Racial tensions arose because of the disproportion between residents and police demographics. Since Newark's black population lived in neighborhoods that had been white only two decades earlier, nearly all of their apartments and stores were white-owned as well. The loss of jobs affected overall income in the city, and many owners cut back on maintenance of buildings, contributing to a cycle of deterioration in housing stock.

Remove ads

1967 Newark riots

On July 12, 1967, a taxi driver named John Smith was violently injured while respectfully accepting arrest. A crowd gathered outside the police station where Smith was detained. Due to miscommunication, the crowd believed Smith had died in custody, although he had been transported to a hospital via a back entrance to the station. This sparked scuffles between African Americans and police in the Fourth Ward, although the damage toll was only $2,500.

After television news broadcasts on July 13, however, new and larger riots took place. Twenty-six people were killed, 1,500 were wounded, 1,600 were arrested, and $10 million in property was destroyed. More than a thousand businesses were torched or looted, including 167 groceries (most of which would never reopen). Newark's reputation suffered dramatically. It was said, "wherever American cities are going, Newark will get there first."[46]

The long and short-term causes of the riots are explored in depth in the documentary film Revolution '67.

Remove ads

After the riots

Summarize

Perspective

The 1970s and 1980s brought continued decline. Middle-class residents of all races continued to flee the city. Between 1960 and 1990, Newark lost more than 125,000 residents, one-third of its population, leaving abandoned neighborhoods behind. This led certain pockets of the city to develop as domains of poverty and social isolation. As a result, the neighborhood demolition that began under urban renewal continued into these neighborhoods destroying hundreds of historic structures.[45] Some say that whenever the media of New York needed to find some example of urban despair, they traveled to Newark. A writer at The New York Times Magazine said Newark is "a study in the evils, tensions, and frustrations that beset the central cities of America" and Newsweek stated that Newark was "a classic example of urban disaster." Late-night talk show hosts routinely made jokes at the expense of Newark's desperate situation. Johnny Carson once quipped "Have you heard?...The city of Newark is under arrest."[4]

In January 1975, an article in Harper's Magazine ranked the 50 largest American cities in 24 categories, ranging from park space to crime. Newark was one of the five worst in 19 out of 24 categories, and the very worst in nine. According to the article, only 70 percent of residents owned a telephone. St. Louis, the city ranked second worst, was much farther from Newark than the cities in the top five were from each other. The article declared Newark as "The Worst American City"[47] and concluded:

The city of Newark stands without serious challenge as the worst city of all. It ranked among the worst cities in no fewer than nineteen of twenty-four categories, and it was dead last in nine of them... Newark is a city that desperately needs help.[48]

In 1980, the documentary, Newark: It's My Home, was released. Hosted by Star-Ledger investigative journalist Gordon Bishop, the film profiled three families living in the city while focusing on the future of urban America.[49][50][51]

While navigating these challenges, Newark had some achievements in the two and a half decades since the riots. In 1968, the New Community Corporation was founded. It has become one of the most successful community development corporations in the nation. By 1987, the NCC owned and managed 2,265 low-income housing units.

Newark's downtown began to redevelop in the post-riot decades. Less than two weeks after the riots, Prudential announced plans to underwrite a $24 million office complex near Penn Station, dubbed "Gateway." While Gateway provided desperately needed tax revenue for Newark, it hurt the city by isolating office workers and their economic activity from the city. The complex's fortress like design and skywalks allows workers to commute to their offices by car or rail without having to set foot on the city streets. Gateway also set the tone for other office buildings in the area, which also lack a real connection with their surroundings. Today, Gateway houses thousands of white-collar workers, though few live in Newark.[52][53]

Before the riots, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey was considering building in the suburbs. The riots and Newark's undeniable desperation kept the medical school in the city. However, instead of being built on 167 acres (676,000 m2), the medical school was built on just 60 acres (240,000 m2), part of which was already city owned, after negotiations with local community organizations as part of the "Newark Accords." However, even with the reduced size of the project, 7,627 residents were displaced through property acquisition and demolition.[54] Students at the medical school soon started the "Student Family Health Care Center" to provide free health care for the underserved population, along with other community service projects. It continues to operate today under Rutgers Health as one of the nation's oldest student-run free health clinics.[55]

In 1970, Kenneth A. Gibson (1970–1986) was the first African-American to be elected mayor of Newark, as well as to be elected mayor of a major northeastern city. The 1970s were a time of battles between Gibson and the shrinking white population. Gibson admitted that "Newark may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation." He and the city council raised taxes to try to improve services such as schools and sanitation, but they did nothing for Newark's economic base. The CEO of Ballantine's Brewery asserted that Newark's $1 million annual tax bill was the cause of the company's bankruptcy.[56]

In 1986, real estate developer Harry Grant met with mayor Sharpe James (1986–2006) and proposed constructing the tallest building in the United States with a 1,750 ft (530 m), 121-story office tower named the Grant USA Tower. It would include a 500-key hotel, convention center, parking garage and a 60,000 sq ft (5,600 m2) indoor shopping mall called "Renaissance Mall" on the Downtown site of the former Central Railroad of New Jersey Broad Street Terminal. Grant offered to self finance the project in return for a 15-year property tax abatement. To garner more support from the city, Grant gifted Newark new flagpoles, sidewalks, a five-story Christmas tree and cladded the dome of Newark City Hall in 24-carat gold leaf. By 1989, Grant had lost support from James after Grant's construction crew ignored a cease-and-desist order on replacing the sidewalk in front of City Hall. Later that year the project was struggling and the Renaissance Mall was half constructed when Grant declared bankruptcy and abandoned the project leaving the mall an unfinished blighted construction site and eye sore for 16 years.[57]

In 1996, Money magazine ranked Newark "The Most Dangerous City in the Nation." The magazine cited that Newark had the nation's highest violent crime rate at six times the United States average with roughly 1 in 25 residents being a victim of violent crime. Additionally, the city's auto theft rate was also six times the national average.[58]

In American Pastoral, the 1997 novel by Newark-born author Philip Roth, the protagonist Swede Levov says:

Newark used to be the city where they manufactured everything, now it's the car theft capital of the world ... there was a factory where somebody was making something on every side street. Now there's a liquor store on every street — a liquor store, a pizza stand, and a seedy storefront church. Everything else is in ruins or boarded up.

During the 1990s, Newark started to be referred to as the Brick City. The nickname came from young Newark residents living in the brick high-rise public housing projects of the Newark Housing Authority that once occupied the core of the Central Ward. These numerous housing projects left a nickname on the city as part of their legacy that has been enshrined in music from local artists such as the Outsidaz, the Fugees and Redman.[59][60][61]

Prior to the election of former mayor Cory Booker (2006–2013) in 2006, Newark did not have a formal city planning department. As a result, Julia Vitullo-Martin, an urban planner and a fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, concluded:

Newark is a living laboratory for nearly every bad planning idea of the 20th century. Urban renewal destroyed whole neighborhoods, replacing low-rise, vernacular residences with public housing projects. Built on superblocks, the projects wiped out the original grid as well as commercial and retail activity. Interstate highways cut the city into pieces, dividing and isolating neighborhoods. And crime, of course, made sport of the general civic unraveling. Corporations, most prominently Prudential Insurance, tried to help. But to protect employees from the deteriorating environment, they built fortress-like towers, connected to the train station and to one another by skywalks, bypassing the streets below and walling off the waterfront with parking garages and hostile architecture. Meanwhile, surface roads were widened to facilitate traffic, making escape to the suburbs more efficient. Gradually, shops and restaurants closed, leaving a few dejected discount stores behind.[62][63]

By the mid-first decade of the 21st century, the rate of crime had fallen by 58% from historic highs associated with severe drug problems in the mid-1990s, however homicides remained at record highs for a city of its size with a per capita homicide rate three times that of nearby New York City.[64] In the first two months of 2008, the homicide rate dropped dramatically, with no homicides recorded for 43 days.[65] However, even with progress made to reduce crime, in 2012 Newark was ranked as the 6th most dangerous city in the United States.[66] In 2013 Newark recorded 111 homicides, the first year ending in triple digits in seven years[67] and the highest tally since 1990, accounting for 27% of all homicides statewide.[68] Since 2016, Newark has been successful in driving down the city's homicide rate to a new "historic low" of 37 homicides in 2024, down from 48 in 2023, the lowest homicide rate since 1960. However, overall violent crime rose 21% after two years of consecutive declines in 2022 and 2023.[69]

Federal monitor of the Newark Police Department

In July 2014, the United States Department of Justice announced that the Newark Police Department (NPD) would be placed under a federal monitor after a three year investigation found the NPD "engaged in a pattern of unconstitutional practices, chiefly in its use of force, stop-and-frisk tactics, unwarranted stops and arrests and discriminatory police actions." Specifically, disproportionately stopping and arresting African Americans to where three-quarters of the stops were deemed unconstitutional, use of excessive force in 20% of incidents, stealing property off of residents and retaliation against those who questioned police actions. The investigation also found that the department's internal affairs bureau was dysfunctional to the point that it had only sustained one complaint of police brutality over a five year period. Newark became the first municipal police department in state history to operate under a federal watchdog and the 13th in the United States.[70] In December 2014, mayor Ras Baraka (2014–present) announced the creation of a Civilian Complaint Review board.[71] In 2016, the city entered into consent decree agreeing to a federal monitoring program and comprehensive reforms. In 2018, the department began a de-escalation training program that they credit for the achievement of no officer discharging their weapon on duty in 2020.[72] Since entering the consent decree, overall crime in Newark has been reduced by 40%.[73] As of 2024, the Newark Police Department is still under federal oversight.[74]

State fiscal oversight

In August 2014, Newark cited a $30.1 million deficit in the city's 2013 budget from the Booker administration and an anticipated $63.4 million deficit for 2014 requiring $93 million to balance its 2014 budget. Mayor Baraka requested emergency aid from New Jersey which would require state oversight and involvement in the city's financial affairs.[75] In September 2014, the city auctioned 61 properties, most of which had been foreclosed, in an attempt to raise funds to address the budget deficit.[76] In October 2014, the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs awarded Newark $10 million in transitional aid, which came with a required oversight memorandum of understanding (MOU). As part of the MOU, state oversight required all senior hires be approved by the state Division of Local Government Services and all programs, including programs that offered grants, be state approved. The state also reduced the budget for the city clerk and expenses for council members by half for 2015 as part of the agreement. The state issued similar requirements in 2008, 2009 and 2012 when Newark requested extra state aid.[77] Additionally, New Jersey criticized the city for not following a 2011 state pension reform law requiring all public workers to contribute more toward their health care premiums. By Newark not collecting those payments from its workers, taxpayers had to make up the difference.[78]

Remove ads

Newark Water Crisis

Summarize

Perspective

Lead concentrations in Newark's water accumulated for several years in the 2010s as a result of inaccurate testing and poor leadership at the Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation (NWCDC). Newark's problem came from a negligence of officials who the city relied on to ensure clean water.[79] The decrease in the quality of the water was due to several factors that were all somewhat interconnected. The primary issue was that lead service pipes that carry water to homes were installed throughout Newark.[80]

Several top officials in Newark denied that their water system had a widespread lead problem, declaring on their website that the water was absolutely safe to drink. Even after municipal water tests revealed the severity of the problem and the city received three noncompliance notices for exceeding lead levels between 2017 and 2018, mayor Ras Baraka denied there was any issue and mailed a brochure to the residents of Newark saying that the drinking water meets all federal standards and was safe to drink. Although the city called an emergency declaration that allowed them to purchase and distribute water filters for faucets, many of the filters were faulty and didn't work.[81] In December 2018, in order to combat the negative publicity of the lead contamination, Newark hired Mercury Public Affairs, the same public relations firm that the former Governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder, hired during the water crisis in Flint, for $225,000.00 even after mayor Baraka rejected comparisons to the Flint water crisis calling them "absolutely and outrageously false statements" via a message on the city's website that was later deleted.[82] Mayor Baraka later called the allegations that he deliberately misled residents "BS" stating "we weren't saying that the water coming out of your tap was safe ... it said the source water is fine. After that, we explained what the problem is. It's misleading to tell people that the water is contaminated."[83]

In February 2024, officials announced that they found three properties with faulty service line replacements by a then un-named third party. The city had those lines replaced same day.[84] In October 2024, it was announced that the company hired to replace a portion of the city's lead service lines, JAS Group Enterprise, Inc., lied, falsified records and never performed the replacement work at 1,500 sites. The EPA stated that any lead pipes that were discovered have been replaced.[85]

Remove ads

Newark's Renaissance

Summarize

Perspective

Downtown

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center, which opened in the downtown area in 1997 at a cost of $180 million, was seen by many as the first step in the city's road to revival, and brought in people to Newark who otherwise might never have visited. NJPAC is known for its acoustics, and features the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra as its resident orchestra. NJPAC also presents a diverse group of visiting artists such as Itzhak Perlman, Sarah Brightman, Sting, 'N Sync, Lauryn Hill, the Vienna Boys' Choir, Yo Yo Ma, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.[86]

In 1999, the city built a now demolished (2019) baseball stadium (Riverfront Stadium) for the Newark Bears, the city's former minor league team that folded in 2013. In 2007, the Prudential Center (nicknamed, "The Rock") opened for the New Jersey Devils on the site of the former abandoned Renaissance Mall. The Newark Public Library underwent a renovation and modest expansion but closed four branches since 2009 due to financial difficulties and facility issues.[87] The Port Authority constructed a monorail connection (AirTrain Newark) to Newark Liberty International Airport Station in 2001. The Newark Light Rail was extended with a one mile (1.6 km) line from Newark Penn Station to Broad Street station in 2006. Since 2010, numerous commercial and residential developments have been built and proposed in the downtown area.[88] Since 2012, two public spaces have opened downtown, Mulberry Commons and Newark Riverfront Park, the latter along Passaic River waterfront is being built from the Ironbound through downtown to provide citizens with access to the riverfront for the first time in over a century.[89]

While most of the city's revitalization efforts have been focused in the downtown area, adjoining neighborhoods have in recent years begun to see some signs of development, particularly in the Central Ward.[90] Between 2000 and 2010, Newark experienced its first population increase since the 1940s. That trend continued between 2010 and 2020 with the city gaining 34,409 (12.4%) residents. Nevertheless, the "Renaissance" has been unevenly felt across the city where some districts continue to have below-average household incomes and higher-than-average rates of poverty. Overall, a quarter of Newark residents live in poverty, more than double the national rate.[91]

Newark's nicknames reflect the efforts to revitalize downtown. In the 1950s the term New Newark was given to the city by then-Mayor Leo Carlin to help convince major corporations to remain in Newark. In the 1960s Newark was nicknamed the Gateway City after the redeveloped Gateway Center area downtown, which shares its name with the tourism region of which Newark is a part, the Gateway Region. It has more recently been called the Renaissance City by the media and the public to gain recognition for its revitalization efforts.[60]

Tech hub

Extensive fiber optic networks in Newark started in the 1990s when telecommunication companies installed fiber optic network to put Newark as a strategic location for data transfer between Manhattan and the rest of the country during the dot-com boom. At the same time, the city encouraged those companies to install more than they needed.[92] A vacant department store was converted into a telecommunication center called 165 Halsey Street.[93] It became one of the world's largest carrier hotels.[94] As a result, after the dot-com bust, there were a surplus of dark fiber (unused fiber optic cables). Twenty years later, the city and other private companies started utilizing the dark fiber to create high performance networks within the city.[92]

Since 2007, several technology oriented companies have moved to Newark: Audible (global headquarters, 2007),[95] Panasonic (North America headquarters, 2013),[96] AeroFarms (global headquarters, 2015),[97] Broadridge Financial Solutions (1,000 jobs, 2017),[98] WebMD (700 jobs, 2021),[99] Ørsted (North American digital operations headquarters, 2021),[100] and HAX Accelerator (US headquarters, 2021).[101]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads