Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

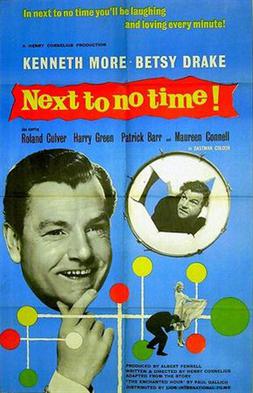

Next to No Time

1958 film by Henry Cornelius From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Next to No Time, also known as Next to No Time! is a 1958 British colour comedy film written and directed by Henry Cornelius and starring Kenneth More, Betsy Drake, John Laurie, Sid James, and Irene Handl.[1] It was based on Paul Gallico's short story "The Enchanted Hour". It was the last feature film completed by Cornelius before his death in 1958.[2] The film concerns an underconfident engineer who is helped by the advice of a ship's barman.

Remove ads

Plot

David Webb is a mild-mannered British planning engineer sent across the Atlantic by his firm to negotiate a deal, a task for which he feels hugely out of his depth. However, a friendly barman, with the aid of a special cocktail, convinces Webb that his personality changes during the hour when the clocks on the ship are stopped as it enters a new time zone.

Cast

- Kenneth More as David Webb

- Betsy Drake as Georgia Brent

- Roland Culver as Sir Godfrey Cowan

- Harry Green as Saul Wiener

- Patrick Barr as Jerry Lane

- Maureen Connell as Mary

- Reginald Beckwith as Warren, Sir Godfrey's secretary

- John Welsh as Steve, the barman

- Bessie Love as Becky Wiener

- Howard Marion-Crawford as Hobbs

- Clive Morton as Wallis

- John Laurie as Abercrombie, Scottish Director

- Raymond Huntley as Factory supervisor

- Eleanor Bryan as Susie

- Irene Handl as Greengrocer

- Sidney James as Cabin Steward

- Ferdy Mayne as Mario

- Rupert Davies as Auction organiser

- Sandra Walden as Hester

- Fred Griffiths as Customer

- Yvonne Buckingham as Mario's girlfriend

- Valerie Buckley as American girl

- Paul Cole as American boy

Remove ads

Production

In March 1957, Cornelius travelled to the United States to find an American co-star to appear opposite Kenneth More.[3]

The film was shot at Shepperton Studios.[1]

Cinematographer Freddie Francis described the film as "a bit of a mess" and said Cornelius was "a lovely man but a bit of a muddler." He suggested that Kenneth More had become somewhat of a "law unto himself" by this time, which may have contributed to the lack of strong direction.[4]

Release

The film premiered at a cinema aboard the RMS Queen Elizabeth, on which some of the film was shot, while the ship was docked at Southampton.[5] It was released in the United States by Rank Distributors of America, marking the first time that company distributed a non-Rank production.[6]

Kinematograph Weekly noted that despite More's presence the film "failed to bring much kudos" at the box office.[7]

Remove ads

Critical reception

Summarize

Perspective

Variety called the film "a flimsy comedy" with "impeccable casting".[8]

The New York Times described it as "thin, transparent and bouncy," likening it to the bubbles cascading around the opening credits.[9]

FilmInk argued that Kenneth More was miscast in a role that would have suited Alec Guinness or Norman Wisdom better, stating that More's natural confidence undermined the "worm turning" device.[10]

Leslie Halliwell called it a "whimsical comedy which never gains momentum."[11]

The Radio Times Guide to Films gave the film 3/5 stars, writing: "This whimsical comedy was something of a disappointment considering it marked the reunion of director Henry Cornelius with his Genevieve star Kenneth More. Sadly, it proved to be Cornelius's last picture before his tragically early death the same year during the production of Law and Disorder. More is curiously out of sorts as an engineer who uses a voyage on the Queen Elizabeth to persuade wealthy Roland Culver to back his latest project. His romantic interest is provided by Betsy Drake, who was then married to Cary Grant."[12]

In British Sound Films: The Studio Years 1928–1959, David Quinlan rated the film as "good," writing: "Pleasant, if uneasy mixture of genres. Smiles rather than guffaws."[13]

Remove ads

Notes

Summarize

Perspective

After Cornelius' death, Monja Danischewsky reflected on how "intensely personal" the film was to the writer-director, stating:

A man of acute introspection and self-examination, he identified himself closely with The Little Guy in the story... The character in the film, played by Kenneth More, is a planning engineer in a large factory who finds a difficulty in convincing his employers of his ability. "I know I've got it in me," the character says in effect, "but when it comes to putting myself over to people, I don't know how to do it." In the course of the story, The Little Guy learns how to do it, and becomes a Big Guy. Remembering his own early struggles to convince people of his ability, studying his own development as a man, ever grateful for the success which his ability and determination attained, Cornelius had a passionate belief that his new film, for all its trappings of comedy, would give help and encouragement to the millions of Little Guys who would be given an opportunity to see it. This perhaps serves best to illustrate his overall attitude towards film-making. From boyhood, he saw the medium as a means of disseminating ideas. And the idea that seemed most to excite him is that in our world, The Big Guy is only The Little Guy who has crossed the rubicon by his belief in himself. His death robs the British cinema of its most serious comedy maker.[2]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads