Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

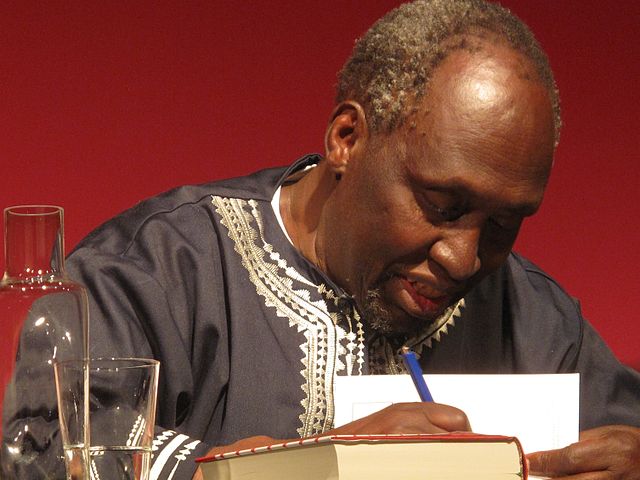

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Kenyan writer and academic (1938–2025) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (Gikuyu: [ᵑɡoɣe wá ðiɔŋɔ];[1] born James Ngugi; 5 January 1938 – 28 May 2025) was a Kenyan author and academic, who has been described as East Africa's leading novelist and an important figure in modern African literature.[2][3][4]

Ngũgĩ wrote primarily in English before switching to writing primarily in Gikuyu and becoming a strong advocate for literature written in native African languages.[5] His works include novels such as the celebrated novel The River Between, plays, short stories, memoirs, children's literature and essays ranging from literary to social criticism. He was the founder and editor of the Gikuyu-language journal Mũtĩiri. His 2016 short story "The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright" has been translated into more than 100[6] languages.[7]

In 1977, Ngũgĩ embarked upon a novel form of theatre in Kenya that sought to liberate the theatrical process from what he held to be "the general bourgeois education system", by encouraging spontaneity and audience participation in the performances.[8] His project sought to "demystify" the theatrical process, and to avoid the "process of alienation [that] produces a gallery of active stars and an undifferentiated mass of grateful admirers" which, according to Ngũgĩ, encourages passivity in "ordinary people".[8] Although his landmark play Ngaahika Ndeenda (1977), co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii, was a commercial success, it was shut down by the then authoritarian Kenyan regime six weeks after its opening.[8]

Ngũgĩ was subsequently imprisoned for more than a year. Adopted as an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience, he was released from prison and fled Kenya.[9] He was appointed Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and English at the University of California, Irvine. He had previously taught at University of Nairobi, Northwestern University, Yale University, and New York University. Ngũgĩ was frequently regarded as a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature.[10][11][12] He won the 2001 International Nonino Prize in Italy, and the 2016 Park Kyong-ni Prize. Among his children are authors Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ[13] and Wanjikũ wa Ngũgĩ.[14]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early years and education

Ngũgĩ was born on 5 January 1938[15][2] in Kamiriithu, near Limuru[16] in Kiambu district, Kenya Colony of the British Empire. He is of Kikuyu descent, and was baptised James Ngugi. His father, Thiong'o wa Ndūcũ,[17][18][19] had four wives and 28 children; Ngũgĩ was born to his third wife, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ.[20][21][22][23] His family were farmers whose land had been repossessed under the British Imperial Land Act of 1915.[17] During Ngũgĩ's childhood, they were caught up in the 1952–1960 Mau Mau Uprising; his half-brother Mwangi was actively involved in the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (in which he was killed), another brother was shot during the State of Emergency, and his mother was tortured at the Kamiriithu home guard post.[18][24][25]

Ngũgĩ left Limuru in 1955 to go to the Alliance High School, a boys' public school about 20 kilometres away.[26] He would later write about the scene of desolation he found on returning home after his first term there: "...the British had razed the entire village to the ground. Kenya was under State of Emergency, the colonial state’s way of trying to isolate the forces of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, waging war against the settler state. My village destroyed, Alliance High School, for the next four years became the new base, from which I looked back at Limuru, the region of my birth. By losing my home, I became more aware of it, the home that I had lost."[26]

Ngũgĩ went on to study at Makerere University College in Kampala, Uganda, from 1959 to 1963, and he said it was in those years in his new country of residence that he found his voice as a writer: "The novels The River Between and Weep Not, Child were the early products of my residency in the country of my educational migration. Uganda enabled me to discover my Kenya and even relive my life in the village. I discovered my home country by being away from the home country."[26] As a student, he attended the African Writers Conference held at Makerere in June 1962,[27][28][29][30] and his play The Black Hermit premiered as part of the event at The National Theatre.[31][32] At the conference, Ngũgĩ asked Chinua Achebe to read the manuscripts of The River Between and Weep Not, Child, which were subsequently published in the Heinemann African Writers Series, launched in London that year, with Achebe as its first advisory editor.[33] Ngũgĩ received his B.A. degree in English from Makerere University College in 1963.[2]

First publications and studies in England

Ngũgĩ's debut novel, Weep Not, Child, was published in May 1964. It was the first novel in English to be published by an African writer from East Africa.[33][34]

Later that year, having won a scholarship to the University of Leeds to study for an MA, Ngũgĩ travelled to England, where he was when his second novel, The River Between, came out in 1965.[33] The River Between, which has the Mau Mau Uprising as its background and describes an unhappy romance between Christians and non-Christians, was previously on Kenya's national secondary school syllabus.[35][36][37] He left Leeds in 1967 without completing his thesis on Caribbean literature,[38] for which his studies had focused on Barbadian writer George Lamming, about whom Ngũgĩ said in his 1972 collection of essays Homecoming: "He evoked for me, an unforgettable picture of a peasant revolt in a white-dominated world. And suddenly I knew that a novel could be made to speak to me, could, with a compelling urgency, touch cords [sic] deep down in me. His world was not as strange to me as that of Fielding, Defoe, Smollett, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Dickens, D. H. Lawrence."[33]

Change of name, ideology and teaching

Ngũgĩ's 1967 novel A Grain of Wheat marked his embrace of Fanonist Marxism.[39] He subsequently renounced writing in English, and the name James Ngugi as colonialist;[40] by 1970 he had changed his name to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o,[41] and began to write in his native Gikuyu.[42] In 1967, Ngũgĩ also began teaching at the University of Nairobi as a professor of English literature. He continued to teach at the university for ten years while serving as a Fellow in Creative Writing at Makerere University. During this time, he also guest-lectured at Northwestern University in the department of English and African Studies for a year.[32]

While a professor at the University of Nairobi, Ngũgĩ was the catalyst of the discussion to abolish the English department. He argued that after the end of colonialism, it was imperative that a university in Africa teach African literature, including oral literature, and that such should be done with the realization of the richness of African languages.[43] In the late 1960s, these efforts resulted in the university dropping English Literature as a course of study, and replacing it with one that positioned African Literature, oral, and written, at the centre.[40]

Imprisonment

In 1976, Ngũgĩ helped to establish The Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre which, among other things, organised African Theatre in the area. The following year saw the publication of Petals of Blood. Its strong political message, and that of his play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii and also published in 1977, provoked the then Kenyan Vice-President Daniel arap Moi to order his arrest. Copies of his play, books by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin were confiscated from him.[25] He was sent to Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, and kept there without a trial for nearly a year.[25]

Ngũgĩ was imprisoned in a cell with other political prisoners. During part of their imprisonment, they were allowed one hour of sunlight a day. In Ngũgĩ's words: "The compound used to be for the mentally deranged convicts before it was put to better use as a cage for 'the politically deranged.'" He found solace in writing and wrote the first modern novel in Gikuyu, Devil on the Cross (Caitaani mũtharaba-Inĩ), on prison-issued toilet paper.[25][44]

During his time in prison, Ngũgĩ decided to cease writing his plays and other works in English and began writing all his creative works in his native tongue, Gikuyu.[32]

Ngũgĩ's time in prison also inspired the play The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976). Written in collaboration with Micere Githae Mugo,[45] The Trial of Dedan Kimathi was performed at FESTAC 77 in Lagos, Nigeria.[46] The play recreates the indomitable courage of the Mau Mau revolutionary and his right-hand person – a woman warrior. While Kimathi remains in jail, it is 'the woman' – representing Kenyan mothers – who tries to free him and in turn train the next generation for the struggle. The role of Kenyan women in the Mau Mau movement (Kenyan freedom struggle) is a historical reality."[47]

After Ngũgĩ's release in December 1978,[32] he was not reinstated to his job as professor at Nairobi University, and his family was harassed. Because he wrote about the injustices of the dictatorial government at the time, Ngũgĩ and his family were forced to live in exile. Only after Daniel Arap Moi, the longest-serving Kenyan president, retired in 2002, was it safe for them to return.[48]

Exile

While in exile, Ngũgĩ worked with the London-based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya (1982–98).[9][32] Matigari ma Njiruungi (translated by Wangui wa Goro into English as Matigari) was published at this time. In 1984, he was a Visiting Professor at Bayreuth University, and the following year was Writer-in-Residence for the Borough of Islington in London.[32] He also studied film at Dramatiska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden (1986).[32]

Ngũgĩ's later works include Detained, his prison diary (1981), Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), an essay arguing for African writers' expression in their native languages rather than European languages, in order to renounce lingering colonial ties and to build authentic African literature, and Matigari (translated by Wangui wa Goro), (1987), one of his most famous works, a satire based on a Gikuyu folk tale.[49] Describing himself as a "literary migrant", he also stated: "I had to be away from my mother tongue to discover my mother tongue."[26]

Ngũgĩ was Visiting Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Yale University between 1989 and 1992.[32] In 1992, he was a guest at the Congress of South African Writers and spent time in Zwide Township with Mzi Mahola, the year he became a professor of Comparative Literature and Performance Studies at New York University, where he held the Erich Maria Remarque Chair. He served as Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and was first director of the International Center for Writing and Translation at the University of California, Irvine.[50]

21st century

On 8 August 2004, Ngũgĩ returned to Kenya as part of a month-long tour of East Africa. On 11 August, robbers broke into his high-security apartment: they assaulted Ngũgĩ, sexually assaulted his wife and stole various items of value.[51] When Ngũgĩ returned to the U.S. at the end of his month-long trip, five men were arrested on suspicion of the crime, including one of his nephews.[48] In 2006, the American publishers Random House published his first new novel in nearly two decades, Wizard of the Crow, translated to English from Gikuyu by the author himself.[52]

On 10 November 2006, while in San Francisco at Hotel Vitale at the Embarcadero, Ngũgĩ was harassed and ordered to leave the hotel by an employee. The event led to a public outcry and angered both African-Americans and members of the African diaspora living in America,[53][54] which led to an apology by the hotel.[55]

Ngũgĩ's later books include Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing (2012), and Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance, a collection of essays published in 2009 making the argument for the crucial role of African languages in "the resurrection of African memory", about which Publishers Weekly said: "Ngugi's language is fresh; the questions he raises are profound, the argument he makes is clear: 'To starve or kill a language is to starve and kill a people's memory bank.'"[56] This was followed by two well-received autobiographical works: Dreams in a Time of War: a Childhood Memoir (2010)[57][58][59][60][61] and In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012), which was described as "brilliant and essential" by the Los Angeles Times,[62] among other positive reviews.[63][64][65]

There was perennial speculation about Ngũgĩ being a likely candidate to win the Nobel Prize in Literature,[66] and he had been considered a firm favourite in 2010.[11][12][67] However, that year it was awarded to Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, and afterwards Ngũgĩ was reported as saying that he was less disappointed than the photographers who had gathered outside his home: "I was the one who was consoling them!"[68]

Ngũgĩ's 2016 short story The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright became "the single most translated short story in the history of African writing",[69] now with versions in more than 100 languages.[6] Originally written in Gikuyu (as "Ituĩka Rĩa Mũrũngarũ: Kana Kĩrĩa Gĩtũmaga Andũ Mathiĩ Marũngiĩ"), with an English translation by the author himself, alongside translations into numerous African languages, it was released by the Jalada Africa Trust, a Pan-African writers' collective, in its inaugural Translation Issue,[70][71] starting a project that aimed to translate each story into 2,000 African languages.[7][69] In 2019, The Upright Revolution, Or Why Humans Walk Upright, illustrated by Sunandini Banerjee, was published by Seagull Books.[72]

Ngũgĩ's book The Perfect Nine, originally written and published in Gikuyu as Kenda Muiyuru: Rugano Rwa Gikuyu na Mumbi (2019), was translated into English by Ngũgĩ for its 2020 publication, and is a reimagining in epic poetry of his people's origin story.[73] It was described by the Los Angeles Times as "a quest novel-in-verse that explores folklore, myth and allegory through a decidedly feminist and pan-African lens."[74] The review in World Literature Today said:

"Ngũgĩ crafts a beautiful retelling of the Gĩkũyũ myth that emphasizes the noble pursuit of beauty, the necessity of personal courage, the importance of filial piety, and a sense of the Giver Supreme – a being who represents divinity, and unity, across world religions. All these things coalesce into dynamic verse to make The Perfect Nine a story of miracles and perseverance; a chronicle of modernity and myth; a meditation on beginnings and endings; and a palimpsest of ancient and contemporary memory, as Ngũgĩ overlays the Perfect Nine's feminine power onto the origin myth of the Gĩkũyũ people of Kenya in a moving rendition of the epic form."[75]

Fiona Sampson writing in The Guardian concluded that The Perfect Nine is "a beautiful work of integration that not only refuses distinctions between 'high art' and traditional storytelling, but supplies that all-too rare human necessity: the sense that life has meaning."[76]

In March 2021, The Perfect Nine became the first work written in an indigenous African language to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize, with Ngũgĩ becoming the first nominee as both the author and translator of the book.[77][78]

When asked in 2023 whether Kenyan English or Nigerian English were now local languages, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o responded: "It's like the enslaved being happy that theirs is a local version of enslavement. English is not an African language. French is not. Spanish is not. Kenyan or Nigerian English is nonsense. That's an example of normalised abnormality. The colonised trying to claim the coloniser's language is a sign of the success of enslavement."[40] In 2025, he commented "In Kenya, even today, we have children and their parents who cannot speak their mother tongues... They are very happy when they speak English and even happier when their children don’t know their mother tongue. That’s why I call it mental colonization." He also commented that he had no issue speaking English, but that "I don’t want it to be my primary language... if you know all the languages of the world, and you don’t know your mother tongue, that’s enslavement, mental enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue, and add other languages, that is empowerment."[79]

Remove ads

Personal life

Family

Four of his children are also published authors: Tee Ngũgĩ, Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, Nducu wa Ngũgĩ, and Wanjikũ wa Ngũgĩ.[74][80][81][82][83][84]

Illness and death

In 1995, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o was diagnosed with prostate cancer and was told he had three months to live; nevertheless, he recovered. In 2019, he had triple bypass heart surgery, and around this time, began to struggle with kidney failure. He died in Buford, Georgia, United States on 28 May 2025, at the age of 87. At the time of his death, Ngũgĩ was reportedly receiving kidney dialysis treatments, but his immediate cause of death was not announced.[85][86][87][88]

After Ngũgĩ's death, Western news outlets highlighted his efforts to fight colonialism and other social critiques.[89][90][91][92] Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, fellow Kenyan writer David Gian Maillu, Kenyan President William Ruto, and politicians Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka, and Raila Odinga paid tribute to Ngũgĩ following his death.[93]

Remove ads

Awards and honours

- 1966: UNESCO First Prize for his debut novel Weep Not Child, at the first World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar, Senegal[94][95][96]

- 1973: The Lotus Prize for Literature, at Alma Atta, Khazakhistan[96]

- 1992 (6 April): The Paul Robeson Award for Artistic Excellence, Political Conscience and Integrity, in Philadelphia, U.S.[97]

- 1992 (October): honoured by New York University by being appointed to the Erich Maria Remarque Professorship in Languages to "acknowledge extraordinary scholarly achievement, strong leadership in the University Community and the Profession and significant contribution to our educational mission."[98]

- 1993: The Zora Neale Hurston-Paul Robeson Award, for artistic and scholarly achievement, awarded by the National Council for Black Studies, in Accra, Ghana[97]

- 1994 (October): The Gwendolyn Brooks Center Contributors Award for significant contribution to The Black Literary Arts[97]

- 1996: The Fonlon-Nichols Prize, New York, for Artistic Excellence and Human Rights[97]

- 2001: Nonino International Prize for Literature[99][100]

- 2002 (July): Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature, UCI.[97]

- 2002 (October): Medal of the Presidency of the Italian Cabinet Awarded by the International Scientific Committee of the Pio Manzù Centre, Rimini, Italy.[97]

- 2003 (May): Honorary Foreign Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[101]

- 2006: Wizard of the Crow is No. 3 on Time magazine's Top 10 Books of the Year (European edition)[102]

- 2006: Wizard of the Crow is one of The Economist's Best Books of the Year[103][104]

- 2006: Wizard of the Crow is one of Salon.com's picks for Best Fiction of the year[105]

- 2007: Wizard of the Crow – shortlisted for the 2007 Commonwealth Writers' Prize Best Book – Africa.[106]

- 2007: Wizard of the Crow - Gold medal winner in Fiction for the 2007 California Book Awards[107]

- 2007: Wizard of the Crow – finalist for the 2007 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for Black Literature[108]

- 2008: Wizard of the Crow nominated for the 2008 IMPAC Dublin Award[109]

- 2008 (2 April): Order of the Elder of Burning Spear (Kenya Medal – conferred by Kenya's Ambassador to the United States in Los Angeles).[97]

- 2008 (24 October): Grinzane for Africa Award[97]

- 2008: Dan and Maggie Inouye Distinguished Chair in Democratic Ideals, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.[110]

- 2009: Shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize[111][112]

- 2012: National Book Critics Circle Award (finalist Autobiography) for In the House of the Interpreter[113]

- 2012 (31 March): W.E.B. Du Bois Award, National Black Writers Conference, New York.[114]

- 2013 (October): UCI Medal[97]

- 2014: Elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences[115]

- 2014: Nicolás Guillén Lifetime Achievement Award for Philosophical Literature[116]

- 2014 (16 November): Honoured at Archipelago Books' 10th anniversary gala in New York.[117]

- 2016: Park Kyong-ni Prize[118]

- 2016 (14 December): Sanaa Theatre Awards/Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of excellence in Kenyan Theatre, Kenya National Theatre.[119]

- 2017: Los Angeles Review of Books/UCR Creative Writing Lifetime Achievement Award[120]

- 2018: Grand Prix des mécènes of the GPLA 2018, for his entire body of work.[121]

- 2019: Premi Internacional de Catalunya Award for his Courageous work and Advocacy for African languages[96]

- 2019: Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize[97]

- 2021: Longlisted for the International Booker Prize for The Perfect Nine[77]

- 2021: Elected a Royal Society of Literature International Writer[122]

- 2021: EBRD Literature Prize[96]

- 2022: PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature[123]

Honorary degrees

- Albright College, Doctor of Humane Letters honoris causa, 1994[97]

- Roskilde University, Honorary Doctor, Denmark, 1997[97]

- University of Leeds, Honorary doctorate of Letters (LittD), 2004[97]

- Walter Sisulu University (formerly U. Transkei), South Africa, Honorary Degree, Doctor of Literature and Philosophy, July 2004.[97]

- California State University, Dominguez Hills, Honorary Degree, Doctor of Humane Letters, May 2005.[97]

- Dillard University, New Orleans, Honorary Degree, Doctor of Humane Letters, May 2005.[97]

- University of Auckland, Honorary doctorate of Letters (LittD), 2005[97]

- New York University, Honorary Degree, Doctor of Letters, 15 May 2008[97]

- University of Dar es Salaam, Honorary doctorate in Literature, 2013[124]

- University of Bayreuth, Honorary doctorate (Dr. phil. h.c.), 2014[100]

- KCA University, Kenya, Honorary Doctorate degree of Human Letters (honoris causa) in Education, 27 November 2016[97]

- Yale University, Honorary doctorate (D.Litt. h.c.), 2017[125]

- University of Edinburgh, Honorary doctorate (D.Litt.), 2019[126]

Remove ads

Publications

Novels

- Weep Not, Child (1964), ISBN 978-0143026242[97]

- The River Between (1965), ISBN 0-435-90548-1[97]

- A Grain of Wheat (1967, 1992), ISBN 0-14-118699-2[97]

- Petals of Blood (1977), ISBN 0-14-118702-6[97]

- Caitaani Mutharaba-Ini (Devil on the Cross, 1980)[97]

- Matigari ma Njiruungi, 1986 (Matigari, translated into English by Wangui wa Goro, 1989), ISBN 0-435-90546-5[97]

- Mũrogi wa Kagogo (Wizard of the Crow, 2006), ISBN 9966-25-162-6[97]

- The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi (2020)[127]

Short-story collections

- A Meeting in the Dark (1974)[128]

- Secret Lives, and Other Stories (1976, 1992), ISBN 0-435-90975-4[129]

- Minutes of Glory and Other Stories (2019)[130]

Plays

- The Black Hermit (1963)[97]

- This Time Tomorrow (three plays, including the title play "This Time Tomorrow", "The Rebels", and "The Wound in the Heart") (1970)[131]

- The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976), ISBN 0-435-90191-5, African Publishing Group, ISBN 0-949932-45-0 (written with Micere Githae Mugo)[128]

- Ngaahika Ndeenda: Ithaako ria ngerekano (I Will Marry When I Want) (1977, 1982) (with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii)[97]

- Mother, Sing for Me (1986)[132]

Memoirs

- Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary (1981)[97]

- Dreams in a Time of War: a Childhood Memoir (2010), ISBN 978-1-84655-377-6[97]

- In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012), ISBN 978-0-30790-769-1[133]

- Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Memoir of a Writer's Awakening (2016), ISBN 978-1-62097-240-3[134]

- Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir (2018)[135]

Other non-fiction

- Homecoming: Essays on African and Caribbean Literature, Culture and Politics. Lawrence Hill and Company. 1972. ISBN 978-0-435-18580-0.[97]

- Education for a National Culture (1981)[128]

- Barrel of a Pen: Resistance to Repression in Neo-Colonial Kenya (1983)[128]

- Writing against Neo-Colonialism (1986)[128]

- Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), ISBN 978-0852555019[97]

- Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms (1993), ISBN 978-0852555309[97]

- Penpoints, Gunpoints and Dreams: The Performance of Literature and Power in Post-Colonial Africa (The Clarendon Lectures in English Literature 1996), Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-818390-9[136]

- Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance (2009), ISBN 978-0-465-00946-6[137]

- Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing (2012), ISBN 978-0231159517 JSTOR[97]

- Secure the Base: Making Africa Visible in the Globe (2016), ISBN 978-0857423139[138][139]

- The Language of Languages (2023), ISBN 978-1-80309-071-9[140]

- Decolonizing Language and Other Revolutionary Ideas (2025)[44]

Children's books

- Njamba Nene and the Flying Bus (translated by Wangui wa Goro) (Njamba Nene na Mbaathi i Mathagu, 1986)[141]

- Njamba Nene and the Cruel Chief (translated by Wangui wa Goro) (Njamba Nene na Chibu King'ang'i, 1988)[142]

- Njamba Nene's Pistol (Bathitoora ya Njamba Nene, 1990), ISBN 0-86543-081-0[143]

- The Upright Revolution, Or Why Humans Walk Upright (illustrated by Sunandini Banerjee), Seagull Books, 2019, ISBN 9780857426475[72][144]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads