Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Karl Marx

German philosopher (1818–1883) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

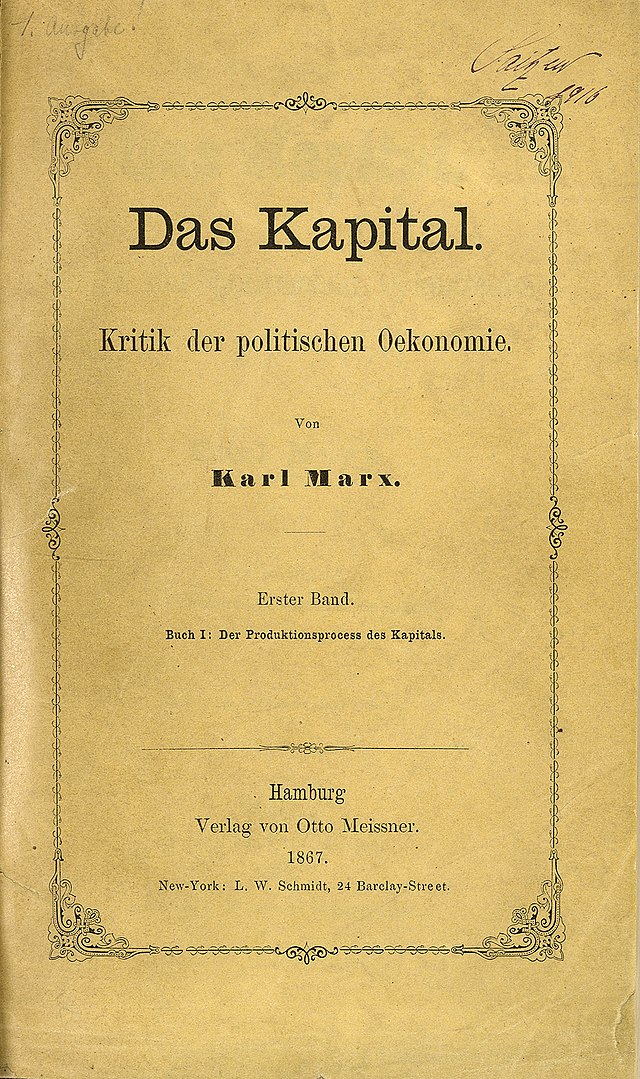

Karl Marx[a] (German: [ˈkaʁl ˈmaʁks]; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto (written with Friedrich Engels), and his three-volume Das Kapital (1867–1894), a critique of classical political economy which employs his theory of historical materialism in an analysis of capitalism, in the culmination of his life's work. Marx's ideas and their subsequent development, collectively known as Marxism, have had enormous influence.

Born in Trier in the Kingdom of Prussia, Marx studied at the University of Bonn and the University of Berlin, and received a doctoral degree in philosophy from the University of Jena in 1841. A Young Hegelian, he was influenced by the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and both critiqued and developed Hegel's ideas in works such as The German Ideology (written 1846) and the Grundrisse (written 1857–1858). While in Paris, Marx wrote his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and met Engels, who became his closest friend and collaborator. After moving to Brussels in 1845, they were active in the Communist League, and in 1848 they wrote The Communist Manifesto, which expresses Marx's ideas and lays out a programme for revolution. Marx was expelled from Belgium and Germany, and in 1849 moved to London, where he wrote The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852) and Das Kapital. From 1864, Marx was involved in the International Workingmen's Association (First International), in which he fought the influence of anarchists led by Mikhail Bakunin. In his Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875), Marx wrote on revolution, the state and the transition to communism. He died stateless in 1883 and was buried in Highgate Cemetery.

Marx's critiques of history, society and political economy hold that human societies develop through class conflict. In the capitalist mode of production, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and the working classes (the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour power for wages.[4] Employing his historical materialist approach, Marx predicted that capitalism produced internal tensions like previous socioeconomic systems and that these tensions would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system known as the socialist mode of production. For Marx, class antagonisms under capitalism—owing in part to its instability and crisis-prone nature—would eventuate the working class's development of class consciousness, leading to their conquest of political power and eventually the establishment of a classless, communist society constituted by a free association of producers.[5] Marx actively pressed for its implementation, arguing that the working class should carry out organised proletarian revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic emancipation.[6]

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures of the modern era, and his work has been both lauded and criticised.[7] Marxism has exerted major influence on socialist thought and political movements, with Marxist schools of thought such as Marxism–Leninism and its offshoots becoming the guiding ideologies of revolutions that took power in many countries during the 20th century, forming communist states. Marx's work in economics has had a strong influence on modern heterodox theories of labour and capital,[8][9][10] and he is often cited as one of the principal architects of modern sociology.[11][12]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Childhood and early education: 1818–1836

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818 to Heinrich Marx and Henriette Pressburg, at Brückengasse 664 in Trier, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia.[15] Marx's family was originally non-religious Jewish but had converted formally to Christianity before his birth. His maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi, while his paternal line had supplied Trier's rabbis since 1723, a role taken by his grandfather Meier Halevi Marx.[16] His father was the first in the line to receive a secular education. He became a lawyer with a comfortably upper middle class income and the family owned a number of Moselle vineyards, in addition to his income as an attorney. After Prussia's annexation of the Rhineland in 1815 and the subsequent abrogation of Jewish emancipation,[17] Heinrich converted from Judaism to the state Evangelical Church of Prussia in order to retain his career as a lawyer.[18]

Largely non-religious, Heinrich was a man of the Enlightenment, interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. A classical liberal, he took part in agitation for a constitution and reforms in Prussia, which was then an absolute monarchy.[19] In 1815, Heinrich Marx began working as an attorney and in 1819 moved his family to a ten-room property near the Porta Nigra.[20] His wife, Henriette Pressburg, was a Dutch Jew from a prosperous business family that later founded the company Philips Electronics. Her sister Sophie Pressburg married Lion Philips and was the grandmother of both Gerard and Anton Philips and great-grandmother to Frits Philips. Lion Philips was a wealthy Dutch tobacco manufacturer and industrialist, upon whom Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely for loans while they were exiled in London.[21]

Little is known of Marx's childhood.[22] The third of nine children, he became the eldest son when his brother Moritz died in 1819.[23] Marx and his surviving siblings were baptised into the Lutheran Church on 28 August 1824,[24] and their mother in November 1825.[25] Marx was privately educated by his father until 1830 when he entered Trier High School (Trier High School), whose headmaster, Hugo Wyttenbach, was a friend of his father. By employing many liberal humanists as teachers, Wyttenbach incurred the anger of the local conservative government. In 1832, police raided the school and discovered that literature promoting political liberalism was being distributed among the students. Viewing the distribution of such material as a seditious act, the authorities implemented reforms and replaced several members of the staff during Marx's time at the school.[26]

In October 1835 at the age of 16, Marx travelled to the University of Bonn wishing to study philosophy and literature, but his father insisted on law as a more practical field.[27] Due to a condition referred to as a "weak chest",[28] Marx was excused from military duty when he turned 18. While at the University at Bonn, Marx joined the Poets' Club, a group containing political radicals that were monitored by the police.[29] Marx also joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society and at one point served as the club's co-president.[30][31] In August 1836 he took part in a duel with a member of the university's Borussian Korps.[32] Although his grades in the first term were good, they soon deteriorated, leading his father to force a transfer to the more serious and academic University of Berlin.[33]

Hegelianism and early journalism: 1836–1843

Trierer students in front of the White Horse, among them, Karl Marx

Karl Marx (detail)

A famous lithograph by David Levi Elkan, simply known as "Die Trierer", depicts several students, and among them, Karl Marx, in front of the White Horse in 1836.[b]

Spending summer and autumn 1836 in Trier, Marx became more serious about his studies and his life. He became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, an educated member of the petty nobility who had known Marx since childhood. As she had broken off her engagement with a young aristocrat to be with Marx, their relationship was socially controversial owing to the differences between their religious and class origins, but Marx befriended her father Ludwig von Westphalen (a liberal aristocrat) and later dedicated his doctoral thesis to him.[35] Seven years after their engagement, on 19 June 1843, they married in a Protestant church in Kreuznach.[36]

In October 1836, Marx arrived in Berlin, matriculating in the university's faculty of law and renting a room in the Mittelstrasse.[37] During the first term, Marx attended lectures of Eduard Gans (who represented the progressive Hegelian standpoint, elaborated on rational development in history by emphasising particularly its libertarian aspects, and the importance of social question) and of Karl von Savigny (who represented the Historical School of Law).[38] Although studying law, he was fascinated by philosophy and looked for a way to combine the two, believing that "without philosophy nothing could be accomplished".[39] Marx became interested in the recently deceased German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose ideas were then widely debated among European philosophical circles.[40] During a convalescence in Stralau, he joined the Doctors Club, a student group which discussed Hegelian ideas, and through them became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young Hegelians in 1837. They gathered around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, with Marx developing a particularly close friendship with Adolf Rutenberg. Like Marx, the Young Hegelians were critical of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions but adopted his dialectical method to criticise established society, politics and religion from a left-wing perspective.[41] Marx's father died in May 1838, resulting in a diminished income for the family.[42] Marx had been emotionally close to his father and treasured his memory after his death.[43]

By 1837, Marx had completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix; a drama, Oulanem; and a number of love poems dedicated to his wife. None of this early work was published during his lifetime.[44] The love poems were published posthumously in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 1.[45] Marx soon abandoned fiction for other pursuits, including the study of English and Italian, art history and the translation of Latin classics.[46] He began co-operating with Bruno Bauer on editing Hegel's Philosophy of Religion in 1840. Marx was also engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,[47] which he completed in 1841. It was described as "a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy".[48] The essay was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided instead to submit his thesis to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his Ph.D. in April 1841.[49] As Marx and Bauer were both atheists, in March 1841 they began plans for a journal entitled Archiv des Atheismus (Atheistic Archives), but it never came to fruition. In July, Marx and Bauer took a trip to Bonn from Berlin. There they scandalised their class by getting drunk, laughing in church and galloping through the streets on donkeys.[50]

Marx was considering an academic career, but this path was barred by the government's growing opposition to classical liberalism and the Young Hegelians.[51] Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, where he became a journalist, writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland News), expressing his early views on socialism and his developing interest in economics. Marx criticised right-wing European governments as well as figures in the liberal and socialist movements, whom he thought ineffective or counter-productive.[52] The newspaper attracted the attention of the Prussian government censors, who checked every issue for seditious material before printing, which Marx lamented: "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear".[53] After the Rheinische Zeitung published an article strongly criticising the Russian monarchy, Tsar Nicholas I requested it be banned, and Prussia's government complied in 1843.[54]

Paris: 1843–1845

In 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new, radical left-wing Parisian newspaper, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), then being set up by the German activist Arnold Ruge to bring together German and French radicals.[55] Therefore Marx and his wife moved to Paris in October 1843. Initially living with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, they found the living conditions difficult, so moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844.[56] Although intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter and the only non-German writer was the exiled Russian anarchist collectivist Mikhail Bakunin.[57] Marx contributed two essays to the paper, "Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right"[58] and "On the Jewish Question",[59] the latter introducing his belief that the proletariat were a revolutionary force and marking his embrace of communism.[60] Only one issue was published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine's satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, leading the German states to ban it and seize imported copies (Ruge nevertheless refused to fund the publication of further issues and his friendship with Marx broke down).[61]

After Jahrbücher's collapse, Marx began writing for Vorwärts! (Forwards!), the only remaining uncensored German-language radical newspaper. Based in Paris, the paper was connected to the League of the Just, a utopian socialist secret society of workers and artisans. Marx attended some of their meetings but did not join.[62] In Vorwärts!, Marx refined his views on socialism based upon Hegelian and Feuerbachian ideas of dialectical materialism, at the same time criticising liberals and other socialists operating in Europe.[63]

On 28 August 1844, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship.[64] Engels showed Marx his recently published The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844,[65][66] convincing Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history.[67][68] Soon, Marx and Engels were collaborating on a criticism of the philosophical ideas of Marx's former friend, Bruno Bauer. This work was published in 1845 as The Holy Family.[69][70] Although critical of Bauer, Marx was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the Young Hegelians Max Stirner and Ludwig Feuerbach, but eventually Marx and Engels abandoned Feuerbachian materialism as well.[71]

During the time that he lived at 38 Rue Vaneau in Paris (from October 1843 until January 1845),[72] Marx engaged in an intensive study of political economy (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill, etc.),[73] the French socialists (especially Claude Henri St. Simon and Charles Fourier)[74] and the history of France.[75] The study of, and critique, of political economy is a project that Marx would pursue for the rest of his life[76] and would result in his major economic work—the three-volume series called Das Kapital.[77] Marxism is based in large part on three influences: Hegel's dialectics, French utopian socialism and British political economy. Together with his earlier study of Hegel's dialectics, the studying that Marx did during this time in Paris meant that all major components of "Marxism" were in place by the autumn of 1844.[78] Marx was constantly being pulled away from his critique of political economy—not only by the usual daily demands of the time, but additionally by editing a radical newspaper and later by organising and directing the efforts of a political party during years of potentially revolutionary popular uprisings of the citizenry. Still, Marx was always drawn back to his studies where he sought "to understand the inner workings of capitalism".[75]

An outline of "Marxism" had definitely formed in the mind of Karl Marx by late 1844. Indeed, many features of the Marxist view of the world had been worked out in great detail, but Marx needed to write down all of the details of his world view to further clarify the new critique of political economy in his own mind.[79] Accordingly, Marx wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts.[80] These manuscripts covered numerous topics, detailing Marx's concept of alienated labour.[81] By the spring of 1845, his continued study of political economy, capital and capitalism had led Marx to the belief that the new critique of political economy he was espousing—that of scientific socialism—needed to be built on the base of a thoroughly developed materialistic view of the world.[82]

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 had been written between April and August 1844, but soon Marx recognised that the Manuscripts had been influenced by some inconsistent ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach. Accordingly, Marx recognised the need to break with Feuerbach's philosophy in favour of historical materialism, thus a year later (in April 1845) after moving from Paris to Brussels, Marx wrote his eleven "Theses on Feuerbach".[83] The "Theses on Feuerbach" are best known for Thesis 11, which states that "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it".[81][84] This work contains Marx's criticism of materialism (for being contemplative), idealism (for reducing practice to theory), and, overall, philosophy (for putting abstract reality above the physical world).[81] It thus introduced the first glimpse at Marx's historical materialism, an argument that the world is changed not by ideas but by actual, physical, material activity and practice.[81][85] In 1845, after receiving a request from the Prussian king, the French government shut down Vorwärts!, with the interior minister, François Guizot, expelling Marx from France.[86]

Brussels: 1845–1848

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium in February 1845. However, to stay in Belgium he had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics.[86] In Brussels, Marx associated with other exiled socialists from across Europe, including Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen and Joseph Weydemeyer. In April 1845, Engels moved from Barmen in Germany to Brussels to join Marx and the growing cadre of members of the League of the Just now seeking home in Brussels.[86][87] Later, Mary Burns, Engels' long-time companion, left Manchester, England, to join Engels in Brussels.[88]

In mid-July 1845, Marx and Engels left Brussels for England to visit the leaders of the Chartists, a working-class movement in Britain. This was Marx's first trip to England and Engels was an ideal guide for the trip. Engels had already spent two years living in Manchester from November 1842[89] to August 1844.[90] Not only did Engels already know the English language,[91] but he had also developed a close relationship with many Chartist leaders.[91] Indeed, Engels was serving as a reporter for many Chartist and socialist English newspapers.[91] Marx used the trip as an opportunity to examine the economic resources available for study in various libraries in London and Manchester.[92]

In collaboration with Engels, Marx also set about writing a book which is often seen as his best treatment of the concept of historical materialism, The German Ideology.[93] In this work, Marx broke with Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Max Stirner and the rest of the Young Hegelians, while he also broke with Karl Grün and other "true socialists" whose philosophies were still based in part on "idealism". In German Ideology, Marx and Engels finally completed their philosophy, which was based solely on materialism as the sole motor force in history.[94] German Ideology is written in a humorously satirical form, but even this satirical form did not save the work from censorship. Like so many other early writings of his, German Ideology would not be published in Marx's lifetime and was published only in 1932.[81][95][96]

After completing German Ideology, Marx turned to a work that was intended to clarify his own position regarding "the theory and tactics" of a truly "revolutionary proletarian movement" operating from the standpoint of a truly "scientific materialist" philosophy.[97] This work was intended to draw a distinction between the utopian socialists and Marx's own scientific socialist philosophy. Whereas the utopians believed that people must be persuaded one person at a time to join the socialist movement, the way a person must be persuaded to adopt any different belief, Marx knew that people would tend, on most occasions, to act in accordance with their own economic interests, thus appealing to an entire class (the working class in this case) with a broad appeal to the class's best material interest would be the best way to mobilise the broad mass of that class to make a revolution and change society. This was the intent of the new book that Marx was planning, but to get the manuscript past the government censors he called the book The Poverty of Philosophy (1847)[98] and offered it as a response to the "petty-bourgeois philosophy" of the French anarchist socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon as expressed in his book The Philosophy of Poverty (1840).[99]

These books laid the foundation for Marx and Engels's most famous work, a political pamphlet that has since come to be commonly known as The Communist Manifesto. While residing in Brussels in 1846, Marx continued his association with the secret radical organisation League of the Just.[100] As noted above, Marx thought the League to be just the sort of radical organisation that was needed to spur the working class of Europe toward the mass movement that would bring about a working-class revolution.[101] However, to organise the working class into a mass movement the League had to cease its "secret" or "underground" orientation and operate in the open as a political party.[102] Members of the League eventually became persuaded in this regard. Accordingly, in June 1847 the League was reorganised by its membership into a new open "above ground" political society that appealed directly to the working classes.[103] This new open political society was called the Communist League.[104] Both Marx and Engels participated in drawing up the programme and organisational principles of the new Communist League.[105]

In late 1847, Marx and Engels began writing what was to become their most famous work – a programme of action for the Communist League. Written jointly by Marx and Engels from December 1847 to January 1848, The Communist Manifesto was first published on 21 February 1848.[106] The Communist Manifesto laid out the beliefs of the new Communist League. No longer a secret society, the Communist League wanted to make aims and intentions clear to the general public rather than hiding its beliefs as the League of the Just had been doing.[107] The opening lines of the pamphlet set forth the principal basis of Marxism: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles".[108] It goes on to examine the antagonisms that Marx claimed were arising in the clashes of interest between the bourgeoisie (the wealthy capitalist class) and the proletariat (the industrial working class). Proceeding on from this, the Manifesto presents the argument for why the Communist League, as opposed to other socialist and liberal political parties and groups at the time, was truly acting in the interests of the proletariat to overthrow capitalist society and to replace it with socialism.[109]

Later that year, Europe experienced a series of protests, rebellions, and often violent upheavals that became known as the Revolutions of 1848.[110] In France, a revolution led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the French Second Republic.[110] Marx was supportive of such activity and having recently received a substantial inheritance from his father (withheld by his uncle Lionel Philips since his father's death in 1838) of either 6,000[111] or 5,000 francs[112][113] he allegedly used a third of it to arm Belgian workers who were planning revolutionary action.[113] Although the veracity of these allegations is disputed,[111][114] the Belgian Ministry of Justice accused Marx of it, subsequently arresting him and he was forced to flee back to France, where with a new republican government in power he believed that he would be safe.[113][115]

Cologne: 1848–1849

Temporarily settling down in Paris, Marx transferred the Communist League executive headquarters to the city and also set up a German Workers' Club with various German socialists living there.[116] Hoping to see the revolution spread to Germany, in 1848 Marx moved back to Cologne where he began issuing a handbill entitled the Demands of the Communist Party in Germany,[117] in which he argued for only four of the ten points of the Communist Manifesto, believing that in Germany at that time the bourgeoisie must overthrow the feudal monarchy and aristocracy before the proletariat could overthrow the bourgeoisie.[118] On 1 June, Marx started the publication of a daily newspaper, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, which he helped to finance through his recent inheritance from his father. Designed to put forward news from across Europe with his own Marxist interpretation of events, the newspaper featured Marx as a primary writer and the dominant editorial influence. Despite contributions by fellow members of the Communist League, according to Friedrich Engels it remained "a simple dictatorship by Marx".[119][120][121]

Whilst editor of the paper, Marx and the other revolutionary socialists were regularly harassed by the police and Marx was brought to trial on several occasions, facing various allegations including insulting the Chief Public Prosecutor, committing a press misdemeanor and inciting armed rebellion through tax boycotting,[122][123][124] although each time he was acquitted.[125][124][126] Meanwhile, the democratic parliament in Prussia collapsed and the king, Frederick William IV, introduced a new cabinet of his reactionary supporters, who implemented counterrevolutionary measures to expunge left-wing and other revolutionary elements from the country.[127] Consequently, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung was soon suppressed, and Marx was ordered to leave the country on 16 May 1849.[121][128] Marx returned to Paris, which was then under the grip of both a reactionary counterrevolution and a cholera epidemic, and was soon expelled by the city authorities, who considered him a political threat. With his wife Jenny expecting their fourth child and with Marx not able to move back to Germany or Belgium, in August 1849 he sought refuge in London.[129][130]

Move to London and further writing: 1850–1860

Marx lived at 28 Dean Street, Soho, London from 1851 to 1856. An English Heritage Blue plaque is visible on the second floor.

Marx moved to London in early June 1849 and would remain based in the city for the rest of his life. The headquarters of the Communist League also moved to London. However, in the winter of 1849–1850, a split within the ranks of the Communist League occurred when a faction within it led by August Willich and Karl Schapper began agitating for an immediate uprising. Willich and Schapper believed that once the Communist League had initiated the uprising, the entire working class from across Europe would rise "spontaneously" to join it, thus creating revolution across Europe. Marx and Engels protested that such an unplanned uprising on the part of the Communist League was "adventuristic" and would be suicide for the Communist League.[131] Such an uprising as that recommended by the Schapper/Willich group would easily be crushed by the police and the armed forces of the reactionary governments of Europe. Marx maintained that this would spell doom for the Communist League itself, arguing that changes in society are not achieved overnight through the efforts and will power of a handful of men.[131] They are instead brought about through a scientific analysis of economic conditions of society and by moving toward revolution through different stages of social development. In the present stage of development (circa 1850), following the defeat of the uprisings across Europe in 1848 he felt that the Communist League should encourage the working class to unite with progressive elements of the rising bourgeoisie to defeat the feudal aristocracy on issues involving demands for governmental reforms, such as a constitutional republic with freely elected assemblies and universal (male) suffrage. In other words, the working class must join with bourgeois and democratic forces to bring about the successful conclusion of the bourgeois revolution before stressing the working-class agenda and a working-class revolution.[citation needed]

After a long struggle that threatened to ruin the Communist League, Marx's opinion prevailed and eventually, the Willich/Schapper group left the Communist League. Meanwhile, Marx also became heavily involved with the socialist German Workers' Educational Society.[132] The Society held their meetings in Great Windmill Street, Soho, central London's entertainment district.[133][134] This organisation was also racked by an internal struggle among its members, some of whom followed Marx while others followed the Schapper/Willich faction. The issues in this internal split were the same issues raised in the internal split within the Communist League, but Marx lost the fight with the Schapper/Willich faction within the German Workers' Educational Society and on 17 September 1850 resigned from the Society.[135]

New-York Daily Tribune and journalism

In the early period in London, Marx committed himself almost exclusively to his studies, such that his family endured extreme poverty.[136][137] His main source of income was Engels, whose own source was his wealthy industrialist father.[137] In Prussia as editor of his own newspaper, and contributor to others ideologically aligned, Marx could reach his audience, the working classes. In London, without finances to run a newspaper themselves, he and Engels turned to international journalism. At one stage they were being published by six newspapers from England, the United States, Prussia, Austria, and South Africa.[138] Marx's principal earnings came from his work as European correspondent, from 1852 to 1862, for the New-York Daily Tribune,[139]: 17 and from also producing articles for more "bourgeois" newspapers. Marx had his articles translated from German by Wilhelm Pieper, until his proficiency in English had become adequate.[140]

The New-York Daily Tribune had been founded in April 1841 by Horace Greeley.[141] Its editorial board contained progressive bourgeois journalists and publishers, among them George Ripley and the journalist Charles Dana, who was editor-in-chief. Dana, a fourierist and an abolitionist, was Marx's contact. The Tribune was a vehicle for Marx to reach a transatlantic public, such as for his "hidden warfare" against Henry Charles Carey.[142] The journal had wide working-class appeal from its foundation; at two cents, it was inexpensive;[143] and, with about 50,000 copies per issue, its circulation was the widest in the United States.[139]: 14 Its editorial ethos was progressive and its anti-slavery stance reflected Greeley's.[139]: 82 Marx's first article for the paper, on the British parliamentary elections, was published on 21 August 1852.[144]

On 21 March 1857, Dana informed Marx that due to the economic recession only one article a week would be paid for, published or not; the others would be paid for only if published. Marx had sent his articles on Tuesdays and Fridays, but, that October, the Tribune discharged all its correspondents in Europe except Marx and B. Taylor, and reduced Marx to a weekly article. Between September and November 1860, only five were published. After a six-month interval, Marx resumed contributions from September 1861 until March 1862, when Dana wrote to inform him that there was no longer space in the Tribune for reports from London, due to American domestic affairs.[145] In 1868, Dana set up a rival newspaper, the New York Sun, at which he was editor-in-chief.[146] In April 1857, Dana invited Marx to contribute articles, mainly on military history, to the New American Cyclopedia, an idea of George Ripley, Dana's friend and literary editor of the Tribune. In all, 67 Marx-Engels articles were published, of which 51 were written by Engels, although Marx did some research for them in the British Museum.[147] By the late 1850s, American popular interest in European affairs waned and Marx's articles turned to topics such as the "slavery crisis" and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 in the "War Between the States".[148] Between December 1851 and March 1852, Marx worked on his theoretical work about the French Revolution of 1848, titled The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon.[149] In this he explored concepts in historical materialism, class struggle, dictatorship of the proletariat, and victory of the proletariat over the bourgeois state.[150]

The 1850s and 1860s may be said to mark a philosophical boundary distinguishing the young Marx's Hegelian idealism and the more mature Marx's[151][152][153][154] scientific ideology associated with structural Marxism.[154] However, not all scholars accept this distinction.[153][155] For Marx and Engels, their experience of the Revolutions of 1848 to 1849 were formative in the development of their theory of economics and historical progression. After the "failures" of 1848, the revolutionary impetus appeared spent and not to be renewed without an economic recession. Contention arose between Marx and his fellow communists, whom he denounced as "adventurists". Marx deemed it fanciful to propose that "will power" could be sufficient to create the revolutionary conditions when in reality the economic component was the necessary requisite. The recession in the United States' economy in 1852 gave Marx and Engels grounds for optimism for revolutionary activity, yet this economy was seen as too immature for a capitalist revolution. Open territories on America's western frontier dissipated the forces of social unrest. Moreover, any economic crisis arising in the United States would not lead to revolutionary contagion of the older economies of individual European nations, which were closed systems bounded by their national borders. When the so-called Panic of 1857 in the United States spread globally, it broke all economic theory models, and was the first truly global economic crisis.[156]

First International and Das Kapital

Marx continued to write articles for the New York Daily Tribune as long as he was sure that the Tribune's editorial policy was still progressive. However, the departure of Charles Dana from the paper in late 1861 and the resultant change in the editorial board brought about a new editorial policy.[158] No longer was the Tribune to be a strong abolitionist paper dedicated to a complete Union victory. The new editorial board supported an immediate peace between the Union and the Confederacy in the Civil War in the United States with slavery left intact in the Confederacy. Marx strongly disagreed with this new political position and in 1863 was forced to withdraw as a writer for the Tribune.[159]

In 1864, Marx became involved in the International Workingmen's Association (known as the First International),[125] to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864.[160] In that organisation, Marx was involved in the struggle against the anarchist wing centred on Mikhail Bakunin.[137] Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to the decline of the International.[161] The most important political event during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the city for two months. In response to the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, "The Civil War in France", a defence of the Commune.[162][163]

Given the repeated failures and frustrations of workers' revolutions and movements, Marx also sought to understand and provide a critique suitable for the capitalist mode of production, and hence spent a great deal of time in the reading room of the British Museum studying.[164] By 1857, Marx had accumulated over 800 pages of notes and short essays on capital, landed property, wage labour, the state, and foreign trade, and the world market, though this work did not appear in print until 1939, under the title Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie (English: Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy).[165][166][167]

In 1859, Marx published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,[168] his first serious critique of political economy. This work was intended merely as a preview of his three-volume Das Kapital (English title: Capital: Critique of Political Economy), which he intended to publish at a later date. In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx began to critically examine axioms and categories of economic thinking.[169][170][171] The work was enthusiastically received, and the edition sold out quickly.[172]

The successful sales of A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy stimulated Marx in the early 1860s to finish work on the three large volumes that would compose his major life's work – Das Kapital and the Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed and critiqued the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo.[137] Theories of Surplus Value is often referred to as the fourth volume of Das Kapital and constitutes one of the first comprehensive treatises on the history of economic thought.[173] In 1867, the first volume of Das Kapital was published, a work which critically analysed capital.[174][171] Das Kapital proposes an explanation of the "laws of motion" of the mode of production from its origins to its future by describing the dynamics of the accumulation of capital, with topics such as the growth of wage labour, the transformation of the workplace, capital accumulation, competition, the banking system, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and land-rents, as well as how waged labour continually reproduce the rule of capital.[175][176][177] Marx proposes that the driving force of capital is in the exploitation of labour, whose unpaid work is the ultimate source of surplus value.

Demand for a Russian language edition of Das Kapital soon led to the printing of 3,000 copies of the book in the Russian language, which was published on 27 March 1872. By the autumn of 1871, the entire first edition of the German-language edition of Das Kapital had been sold out and a second edition was published.

Volumes II and III of Das Kapital remained mere manuscripts upon which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life. Both volumes were published by Engels after Marx's death.[137] Volume II of Das Kapital was prepared and published by Engels in July 1893 under the name Capital II: The Process of Circulation of Capital.[178] Volume III of Das Kapital was published a year later in October 1894 under the name Capital III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole.[179] Theories of Surplus Value derived from the sprawling Economic Manuscripts of 1861–1863, a second draft for Das Kapital, the latter spanning volumes 30–34 of the Collected Works of Marx and Engels. Specifically, Theories of Surplus Value runs from the latter part of the Collected Works' thirtieth volume through the end of their thirty-second volume;[180][181][182] meanwhile, the larger Economic Manuscripts of 1861–1863 run from the start of the Collected Works' thirtieth volume through the first half of their thirty-fourth volume. The latter half of the Collected Works' thirty-fourth volume consists of the surviving fragments of the Economic Manuscripts of 1863–1864, which represented a third draft for Das Kapital, and a large portion of which is included as an appendix to the Penguin edition of Das Kapital, volume I.[183] A German-language abridged edition of Theories of Surplus Value was published in 1905 and in 1910. This abridged edition was translated into English and published in 1951 in London, but the complete unabridged edition of Theories of Surplus Value was published as the "fourth volume" of Das Kapital in 1963 and 1971 in Moscow.[184]

During the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined, and he became incapable of the sustained effort that had characterised his previous work.[137] He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics, particularly in Germany and Russia. His Critique of the Gotha Programme opposed the tendency of his followers Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel to compromise with the state socialist ideas of Ferdinand Lassalle in the interests of a united socialist party.[137] This work is also notable for another famous Marx quote: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need".[185]

In a letter to Vera Zasulich dated 8 March 1881, Marx contemplated the possibility of Russia's bypassing the capitalist stage of development and building communism on the basis of the common ownership of land characteristic of the village mir.[137][186] While admitting that Russia's rural "commune is the fulcrum of social regeneration in Russia", Marx also warned that in order for the mir to operate as a means for moving straight to the socialist stage without a preceding capitalist stage it "would first be necessary to eliminate the deleterious influences which are assailing it [the rural commune] from all sides".[187] Given the elimination of these pernicious influences, Marx allowed that "normal conditions of spontaneous development" of the rural commune could exist.[187] However, in the same letter to Vera Zasulich he points out that "at the core of the capitalist system ... lies the complete separation of the producer from the means of production".[187] In one of the drafts of this letter, Marx reveals his growing passion for anthropology, motivated by his belief that future communism would be a return on a higher level to the communism of our prehistoric past. He wrote:

the historical trend of our age is the fatal crisis which capitalist production has undergone in the European and American countries where it has reached its highest peak, a crisis that will end in its destruction, in the return of modern society to a higher form of the most archaic type – collective production and appropriation.

He added that "the vitality of primitive communities was incomparably greater than that of Semitic, Greek, Roman, etc. societies, and, a fortiori, that of modern capitalist societies".[188] Before he died, Marx asked Engels to write up these ideas, which were published in 1884 under the title The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Family

Marx and von Westphalen had seven children together, but partly owing to the poor conditions in which they lived whilst in London, only three survived to adulthood.[189] Their children were: Jenny Caroline (m. Longuet; 1844–1883); Jenny Laura (m. Lafargue; 1845–1911); Edgar (1847–1855); Henry Edward Guy ("Guido"; 1849–1850); Jenny Eveline Frances ("Franziska"; 1851–1852); Jenny Julia Eleanor (1855–1898) and one more who died before being named (July 1857). According to his son-in-law, Paul Lafargue, Marx was a loving father.[190] In 1962, there were allegations that Marx fathered a son, Freddy,[191] out of wedlock by his housekeeper, Helene Demuth,[192] but the claim is disputed for lack of documented evidence.[193]

Helene Demuth was also largely entrusted as a confidante. In her obituary, penned by Friedrich Engels, her role is revealed as: "Marx took counsel of Helena Demuth, not only in difficult and intricate party matters, but even in respect of his economical writings".[194]

Marx frequently used pseudonyms, often when renting a house or flat, apparently to make it harder for the authorities to track him down. While in Paris, he used that of "Monsieur Ramboz", whilst in London, he signed off his letters as "A. Williams". His friends referred to him as "Moor", owing to his dark complexion and black curly hair, while he encouraged his children to call him "Old Nick" and "Charley".[195] He also bestowed nicknames and pseudonyms on his friends and family, referring to Friedrich Engels as "General", his housekeeper Helene as "Lenchen" or "Nym", while one of his daughters, Jennychen, was referred to as "Qui Qui, Emperor of China" and another, Laura, was known as "Kakadou" or "the Hottentot".[195]

Health

Marx drank heavily after joining the Trier Tavern Club drinking society in the 1830s, and continued to do so until his death.[31]

Marx was afflicted by poor health, what he himself described as "the wretchedness of existence",[196] and various authors have sought to describe and explain it. His biographer Werner Blumenberg attributed it to liver and gall problems which Marx had in 1849 and from which he was never afterward free, exacerbated by an unsuitable lifestyle. The attacks often came with headaches, eye inflammation, neuralgia in the head, and rheumatic pains. A serious nervous disorder appeared in 1877 and protracted insomnia was a consequence, which Marx fought with narcotics.[197]

The illness was aggravated by excessive nocturnal work and faulty diet. Marx was fond of highly seasoned dishes, smoked fish, caviare, pickled cucumbers, "none of which are good for liver patients", but he also liked wine and liqueurs and smoked an enormous amount "and since he had no money, it was usually bad-quality cigars". From 1863, Marx complained a lot about boils: "These are very frequent with liver patients and may be due to the same causes".[197] The abscesses were so bad that Marx could neither sit nor work upright. According to Blumenberg, Marx's irritability is often found in liver patients:

The illness emphasised certain traits in his character. He argued cuttingly, his biting satire did not shrink at insults, and his expressions could be rude and cruel. Though in general Marx had blind faith in his closest friends, nevertheless he himself complained that he was sometimes too mistrustful and unjust even to them. His verdicts, not only about enemies but even about friends, were sometimes so harsh that even less sensitive people would take offence ... There must have been few whom he did not criticize like this ... not even Engels was an exception.[198]

According to Princeton historian Jerrold Seigel, in his late teens, Marx may have had pneumonia or pleurisy, the effects of which led to his being exempted from Prussian military service. In later life whilst working on Das Kapital (which he never completed),[196][199] Marx suffered from a trio of afflictions. A liver ailment, probably hereditary, was aggravated by overwork, a bad diet, and lack of sleep. Inflammation of the eyes was induced by too much work at night. A third affliction, eruption of carbuncles or boils, "was probably brought on by general physical debility to which the various features of Marx's style of life – alcohol, tobacco, poor diet, and failure to sleep – all contributed. Engels often exhorted Marx to alter this dangerous regime". In Seigel's thesis, what lay behind this punishing sacrifice of his health may have been guilt about self-involvement and egoism, originally induced in Karl Marx by his father.[200]

In 2007, a retrodiagnosis of Marx's skin disease was made by dermatologist Sam Shuster of Newcastle University. For Shuster, the most probable explanation was that Marx suffered not from liver problems, but from hidradenitis suppurativa, a recurring infective condition arising from blockage of apocrine ducts opening into hair follicles.[201] Shuster went on to consider the potential psychosocial effects of the disease, noting that the skin is an organ of communication and that hidradenitis suppurativa produces much psychological distress, including loathing and disgust and depression of self-image, mood, and well-being, feelings for which Shuster found "much evidence" in the Marx correspondence. Professor Shuster went on to ask himself whether the mental effects of the disease affected Marx's work and even helped him to develop his theory of alienation.[202]

Death

Following the death of his wife Jenny in December 1881, Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him in London on 14 March 1883, when he died a stateless person at age 64.[203] Family and friends in London buried his body in Highgate Cemetery (East), London, on 17 March 1883 in an area reserved for agnostics and atheists. According to Francis Wheen, there were between nine and eleven mourners at his funeral.[204][205] Research from contemporary sources identifies thirteen named individuals attending the funeral: Friedrich Engels, Eleanor Marx, Edward Aveling, Paul Lafargue, Charles Longuet, Helene Demuth, Wilhelm Liebknecht, Gottlieb Lemke, Frederick Lessner, G Lochner, Sir Ray Lankester, Carl Schorlemmer and Ernest Radford.[206] A contemporary newspaper account claims that twenty-five to thirty relatives and friends attended the funeral.[207]

A writer in The Graphic noted:

By a strange blunder ... his death was not announced for two days, and then as having taken place at Paris. The next day the correction came from Paris; and when his friends and followers hastened to his house in Haverstock Hill, to learn the time and place of burial, they learned that he was already in the cold ground. But for this secresy [sic] and haste, a great popular demonstration would undoubtedly have been held over his grave.[208]

Several of his closest friends spoke at his funeral, including Wilhelm Liebknecht and Friedrich Engels. Engels' speech included the passage:

On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep – but forever.[209]

Marx's surviving daughters Eleanor and Laura, as well as Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue, Marx's two French socialist sons-in-law, were also in attendance.[205] He had been predeceased by his wife and his eldest daughter, the latter dying a few months earlier in January 1883. Liebknecht, a founder and leader of the German Social Democratic Party, gave a speech in German, and Longuet, a prominent figure in the French working-class movement, made a short statement in French.[205] Two telegrams from workers' parties in France and Spain[which?] were also read out.[205] Together with Engels's speech, this constituted the entire programme of the funeral.[205] Non-relatives attending the funeral included three communist associates of Marx: Friedrich Lessner, imprisoned for three years after the Cologne Communist Trial of 1852; G. Lochner, whom Engels described as "an old member of the Communist League"; and Carl Schorlemmer, a professor of chemistry in Manchester, a member of the Royal Society, and a communist activist involved in the 1848 Baden revolution.[205] Another attendee of the funeral was Ray Lankester, a British zoologist who would later become a prominent academic.[205]

Marx left a personal estate valued for probate at £250,[210] equivalent to £38,095 in 2024.[211] Upon his own death in 1895, Engels left Marx's two surviving daughters a "significant portion" of his considerable estate, valued in 2024 at US$6.8 million.[191]

Marx and his family were reburied on a new site nearby in November 1954. The tomb at the new site, unveiled on 14 March 1956,[212] bears the carved message: "Workers of All Lands Unite", the final line of The Communist Manifesto; and, from the 11th "Thesis on Feuerbach" (as edited by Engels), "The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways—the point however is to change it".[213] The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) had the monument with a portrait bust by Laurence Bradshaw erected and Marx's original tomb had only humble adornment.[213]

The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm remarked: "One cannot say Marx died a failure." Although he had not achieved a large following of disciples in Britain, his writings had already begun to make an impact on the left-wing movements in Germany and Russia. Within twenty-five years of his death, the continental European socialist parties that acknowledged Marx's influence on their politics had contributed to significant gains in their representative democratic elections.[214]

Remove ads

Thought

Summarize

Perspective

Influences

Marx's thought demonstrates influence from many sources, including but not limited to:

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's philosophy[215]

- The classical political economy (economics) of Adam Smith and David Ricardo,[216] as well as Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi's critique of laissez-faire economics and analysis of the precarious state of the proletariat[217]

- French socialist thought,[216] in particular the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Henri de Saint-Simon, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Charles Fourier[218][219]

- Earlier German philosophical materialism among the Young Hegelians, particularly that of Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer,[71] as well as the French materialism of the late 18th century, including Diderot, Claude Adrien Helvétius and d'Holbach

- Friedrich Engels' analysis of the working class,[67] as well as the early descriptions of class provided by French liberals and Saint-Simonians such as François Guizot and Augustin Thierry

- Marx's Judaic legacy has been identified as formative to both his moral outlook[220] and his materialist philosophy.[221]

Marx's view of history, which came to be called historical materialism (controversially adapted as the philosophy of dialectical materialism by Engels and Lenin), certainly shows the influence of Hegel's claim that one should view reality (and history) dialectically.[215] However, whereas Hegel had thought in idealist terms, putting ideas in the forefront, Marx sought to conceptualise dialectics in materialist terms, arguing for the primacy of matter over idea.[81][215]

Where Hegel saw the "spirit" as driving history, Marx saw this as an unnecessary mystification, obscuring the reality of humanity and its physical actions shaping the world.[215] He wrote that Hegelianism stood the movement of reality on its head, and that one needed to set it upon its feet.[215] Despite his dislike of mystical terms, Marx used Gothic language in several of his works: in The Communist Manifesto he proclaims "A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre", and in The Capital he refers to capital as "necromancy that surrounds the products of labour".[222]

Though inspired by French socialist and sociological thought,[216] Marx criticised utopian socialists, arguing that their favoured small-scale socialistic communities would be bound to marginalisation and poverty and that only a large-scale change in the economic system could bring about real change.[219][223]

Other important contributions to Marx's revision of Hegelianism came from Engels's book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of class conflict and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution,[67] as well as from the social democrat Friedrich Wilhelm Schulz, who in Die Bewegung der Produktion described the movement of society as "flowing from the contradiction between the forces of production and the mode of production".[224][225]

Marx believed that he could study history and society scientifically, discerning tendencies of history and thereby predicting the outcome of social conflicts. Some followers of Marx, therefore, concluded that a communist revolution would inevitably occur. However, Marx famously asserted in the eleventh of his "Theses on Feuerbach" that "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point however is to change it" and he clearly dedicated himself to trying to alter the world.[6][213]

Marx's theories inspired several theories and disciplines of future, including but not limited to:

Philosophy and social thought

Marx has been called "the first great user of critical method in social sciences", a characterisation stemming from his frequent use of polemics throughout his work to effect critiques of other thinkers.[215][216] He criticised speculative philosophy, equating metaphysics with ideology.[226][227] By adopting this approach, Marx attempted to separate key findings from ideological biases.[216] This set him apart from many contemporary philosophers.[6]

Human nature

The philosophers G.W.F. Hegel (left) and Ludwig Feuerbach, whose ideas on dialectics heavily influenced Marx

Like Tocqueville, who described a faceless and bureaucratic despotism with no identifiable despot,[228] Marx also broke with classical thinkers who spoke of a single tyrant and with Montesquieu, who discussed the nature of the single despot. Instead, Marx set out to analyse "the despotism of capital".[229] Fundamentally, Marx assumed that human history involves transforming human nature, which encompasses both human beings and material objects.[230] Humans recognise that they possess both actual and potential selves.[231][232]

For both Marx and Hegel, self-development begins with an experience of internal alienation stemming from this recognition, followed by a realisation that the actual self, as a subjective agent, renders its potential counterpart an object to be apprehended.[232] Marx further argues that by moulding nature[233] in desired ways[234] the subject takes the object as its own and thus permits the individual to be actualised as fully human. For Marx, the human nature – Gattungswesen, or species-being – exists as a function of human labour.[231][232][234]

Fundamental to Marx's idea of meaningful labour is the proposition that for a subject to come to terms with its alienated object it must first exert influence upon literal, material objects in the subject's world.[235] Marx acknowledges that Hegel "grasps the nature of work and comprehends objective man, authentic because actual, as the result of his own work",[236] but characterises Hegelian self-development as unduly "spiritual" and abstract.[237]

Marx thus departs from Hegel by insisting that "the fact that man is a corporeal, actual, sentient, objective being with natural capacities means that he has actual, sensuous objects for his nature as objects of his life-expression, or that he can only express his life in actual sensuous objects".[235] Consequently, Marx revises Hegelian "work" into material "labour" and in the context of human capacity to transform nature the term "labour power".[81]

Labour, class struggle and false consciousness

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

— Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto[238]

Marx had a special concern with how people relate to their own labour power.[239] He wrote extensively about this in terms of the problem of alienation.[240] As with the dialectic, Marx began with a Hegelian notion of alienation but developed a more materialist conception.[239] Capitalism mediates social relationships of production (such as among workers or between workers and capitalists) through commodities, including labour, that are bought and sold on the market.[239] For Marx, the possibility that one may give up ownership of one's own labour – one's capacity to transform the world – is tantamount to being alienated from one's own nature and it is a spiritual loss.[239] Marx described this loss as commodity fetishism, in which the things that people produce, commodities, appear to have a life and movement of their own to which humans and their behaviour merely adapt.[241]

Commodity fetishism provides an example of what Engels called "false consciousness",[242] which relates closely to the understanding of ideology. By "ideology", Marx and Engels meant ideas that reflect the interests of a particular class at a particular time in history, but which contemporaries see as universal and eternal.[243] Marx and Engels's point was not only that such beliefs are at best half-truths, as they serve an important political function. Put another way, the control that one class exercises over the means of production include not only the production of food or manufactured goods but also the production of ideas (this provides one possible explanation for why members of a subordinate class may hold ideas contrary to their own interests).[81][244]

Marx was an outspoken opponent of child labour,[245] saying that British industries "could but live by sucking blood, and children's blood too", and that U.S. capital was financed by the "capitalized blood of children".[222][246]

Religion

Marx agreed with Ludwig Feuerbach that religion is a human construct reflecting human conditions ("man creates religion, religion does not create man"), but analysed this in historical, not abstract terms. He saw religion as both an expression of suffering and a protest against it. In his 1843 essay Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, Marx sought to distance himself from Young Hegelians like Bruno Bauer, whose religion-focused critique, in his view, could not be a solution to human suffering without a transformative critique of society. Critique of religion would be ineffective without changing the real social conditions of which religion is only an expression.[247]

According to Shlomo Avineri, the famous passage from the introduction to this essay is, though often only partially quoted, "both more complex and more profound" than would seem, and Marx here expressed "empathy, not scorn" for religious feelings:[247]

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.[248]

Similar to the later views of Max Weber, Marx believed that religion plays a legitimating function for the dominant classes by providing a divine sanction for inequality and existing social conditions, and that for subordinate classes religion offers an escape:[249] like an opiate, alleviating pain but not offering a cure.[247] Marx's gymnasium senior thesis at the Gymnasium zu Trier argued that religion had as its primary social aim the promotion of solidarity.[citation needed]

Critique of political economy, history and society

But you Communists would introduce community of women, screams the whole bourgeoisie in chorus. The bourgeois sees in his wife a mere instrument of production. He hears that the means of production are to be exploited in common, and, naturally, can come to no other conclusion than that the lot of being common to all will likewise fall to the women. He has not even a suspicion that the real point aimed at is to do away with the status of women as mere mean of production.

—Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto[250]

Marx's thoughts on labour and its function in reproducing capital were related to the primacy he gave to social relations in determining the society's past, present and future.[215][251][252] Critics have called this economic determinism. Labour is the precondition for the existence of, and accumulation of capital, which both shape the social system.[252] For Marx, social change was driven by conflict between opposing interests, by parties situated in the historical situation of their mode of production.[176] This became the inspiration for the body of works known as the conflict theory.[251]

In his evolutionary model of history, he argued that human history began with free, productive and creative activities that was over time coerced and dehumanised, a trend most apparent under capitalism.[215] Marx noted that this was not an intentional process, but rather due to the immanent logic of the current mode of production which demands more human labour (abstract labour) to reproduce the social relationships of capital.[175][177]

The organisation of society depends on means of production. The means of production are all things required to produce material goods, such as land, natural resources, and technology but not human labour. The relations of production are the social relationships people enter into as they acquire and use the means of production.[251] Together, these compose the mode of production and Marx distinguished historical eras in terms of modes of production. Marx differentiated between base and superstructure, where the base (or substructure) is the economic system and superstructure is the cultural and political system.[251] Marx regarded this mismatch between economic base and social superstructure as a major source of social conflict.[251]

Despite Marx's stress on the critique of capitalism and discussion of the new communist society that should replace it, his explicit critique is guarded, as he saw it as an improved society compared to the past ones (slavery and feudalism).[81] Marx never clearly discusses issues of morality and justice, but scholars agree that his work contained implicit discussion of those concepts.[81]

A mural by Diego Rivera showing Karl Marx, in the National Palace in Mexico City

Marx's view of capitalism was two-sided.[81][152] On one hand, in the 19th century's deepest critique of the dehumanising aspects of this system he noted that defining features of capitalism include alienation, exploitation and recurring, cyclical depressions leading to mass unemployment. On the other hand, he characterised capitalism as "revolutionising, industrialising and universalising qualities of development, growth and progressivity" (by which Marx meant industrialisation, urbanisation, technological progress, increased productivity and growth, rationality, and scientific revolution) that are responsible for progress, at in contrast to earlier forms of societies.[81][152][215]

Marx considered the capitalist class to be one of the most revolutionary in history because it constantly improved the means of production, more so than any other class in history and was responsible for the overthrow of feudalism.[219][253] Capitalism can stimulate considerable growth because the capitalist has an incentive to reinvest profits in new technologies and capital equipment.[239]

According to Marx, capitalists take advantage of the difference between the labour market and the market for whatever commodity the capitalist can produce. Marx observed that in practically every successful industry, input unit-costs are lower than output unit-prices. Marx called the difference "surplus value" and argued that it was based on surplus labour, the difference between what it costs to keep workers alive, and what they can produce.[81] Although Marx describes capitalists as vampires sucking worker's blood,[215] he notes that drawing profit is "by no means an injustice" since Marx, according to Allen W. Wood "excludes any trans-epochal standpoint from which one can comment" on the morals of such particular arrangements.[81] Marx also noted that even the capitalists themselves cannot go against the system.[219] The problem is the "cancerous cell" of capital, understood not as property or equipment, but the social relations between workers and owners, (the selling and purchasing of labour power) – the societal system, or rather mode of production, in general.[219]

At the same time, Marx stressed that capitalism was unstable and prone to periodic crises.[95] He suggested that over time capitalists would invest more and more in new technologies and less and less in labour.[81] Since Marx believed that profit derived from surplus value appropriated from labour, he concluded that the rate of profit would fall as the economy grows.[254] Marx believed that increasingly severe crises would punctuate this cycle of growth and collapse.[254] Moreover, he believed that in the long-term, this process would enrich and empower the capitalist class and impoverish the proletariat.[254][219] In section one of The Communist Manifesto, Marx describes feudalism, capitalism, and the role internal social contradictions play in the historical process:

We see then: the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were generated in feudal society. At a certain stage in the development of these means of production and of exchange, the conditions under which feudal society produced and exchanged ... the feudal relations of property became no longer compatible with the already developed productive forces; they became so many fetters. They had to be burst asunder; they were burst asunder. Into their place stepped free competition, accompanied by a social and political constitution adapted in it, and the economic and political sway of the bourgeois class. A similar movement is going on before our own eyes ... The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring order into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property.[4]

Marx believed that those structural contradictions within capitalism necessitate its end, giving way to socialism, or a post-capitalistic, communist society:

The development of modern industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.[4]

Thanks to various processes overseen by capitalism, such as urbanisation, the working class, the proletariat, should grow in numbers and develop class consciousness, in time realising that they can and must change the system.[215] Marx believed that if the proletariat were to seize the means of production, they would encourage social relations that would benefit everyone equally, abolishing the exploiting class and introducing a system of production less vulnerable to cyclical crises.[215] Marx argued in The German Ideology that capitalism will end through the organised actions of an international working class:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality will have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.[255]

In this new society, the alienation would end and humans would be free to act without being bound by selling their labour.[254] It would be a democratic society, enfranchising the entire population.[219] In such a utopian world, there would also be little need for a state, whose goal was previously to enforce the alienation.[254] Marx theorised that between capitalism and the establishment of a socialist/communist system, would exist a period of dictatorship of the proletariat – where the working class holds political power and forcibly socialises the means of production.[219] As he wrote in his Critique of the Gotha Program, "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".[256] While he allowed for the possibility of peaceful transition in some countries with strong democratic institutional structures (such as Britain, the United States, and the Netherlands), he suggested that in other countries in which workers cannot "attain their goal by peaceful means" the "lever of our revolution must be force".[257]

International relations

Marx viewed Russian Tsarism as the main threat to European revolutions.[258] During the Crimean War, Marx backed the Ottoman Empire and its allies Britain and France against Russia.[258] He was absolutely opposed to Pan-Slavism, viewing it as an instrument of Russian foreign policy.[258] Marx considered the Slavic nations except Poles as 'counter-revolutionary'. Marx and Engels published in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in February 1849:

To the sentimental phrases about brotherhood which we are being offered here on behalf of the most counter-revolutionary nations of Europe, we reply that hatred of Russians was and still is the primary revolutionary passion among Germans; that since the revolution [of 1848] hatred of Czechs and Croats has been added, and that only by the most determined use of terror against these Slav peoples can we, jointly with the Poles and Magyars, safeguard the revolution. We know where the enemies of the revolution are concentrated, viz. in Russia and the Slav regions of Austria, and no fine phrases, no allusions to an undefined democratic future for these countries can deter us from treating our enemies as enemies. Then there will be a struggle, an "inexorable life-and-death struggle", against those Slavs who betray the revolution; an annihilating fight and ruthless terror – not in the interests of Germany, but in the interests of the revolution!"[259]

Marx and Engels sympathised with the Narodnik revolutionaries of the 1860s and 1870s. When the Russian revolutionaries assassinated Tsar Alexander II of Russia, Marx expressed the hope that the assassination foreshadowed 'the formation of a Russian commune'.[260] Marx supported the Polish uprisings against tsarist Russia.[258] He said in a speech in London in 1867:

In the first place the policy of Russia is changeless... Its methods, its tactics, its manoeuvres may change, but the polar star of its policy – world domination – is a fixed star. In our times only a civilised government ruling over barbarian masses can hatch out such a plan and execute it. ... There is but one alternative for Europe. Either Asiatic barbarism, under Muscovite direction, will burst around its head like an avalanche, or else it must re-establish Poland, thus putting twenty million heroes between itself and Asia and gaining a breathing spell for the accomplishment of its social regeneration.[261]

Marx supported the cause of Irish independence. In 1867, he wrote Engels: "I used to think the separation of Ireland from England impossible. I now think it inevitable. The English working class will never accomplish anything until it has got rid of Ireland. ... English reaction in England had its roots ... in the subjugation of Ireland."[262]

Marx spent some time in French Algeria, which had been invaded and made a French colony in 1830, and had the opportunity to observe life in colonial North Africa. He wrote about the colonial justice system, in which "a form of torture has been used (and this happens 'regularly') to extract confessions from the Arabs; naturally it is done (like the English in India) by the 'police'; the judge is supposed to know nothing at all about it."[263] Marx was surprised by the arrogance of many European settlers in Algiers and wrote in a letter:

when a European colonist dwells among the 'lesser breeds,' either as a settler or even on business, he generally regards himself as even more inviolable than handsome William I [a Prussian king]. Still, when it comes to bare-faced arrogance and presumptuousness vis-à-vis the 'lesser breeds,' the British and Dutch outdo the French.[263]

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Marx's analysis of colonialism as a progressive force bringing modernization to a backward feudal society sounds like a transparent rationalization for foreign domination. His account of British domination, however, reflects the same ambivalence that he shows towards capitalism in Europe. In both cases, Marx recognizes the immense suffering brought about during the transition from feudal to bourgeois society while insisting that the transition is both necessary and ultimately progressive. He argues that the penetration of foreign commerce will cause a social revolution in India.[264]

Marx discussed British colonial rule in India in the New York Herald Tribune in 1853:

There cannot remain any doubt but that the misery inflicted by the British on Hindostan [India] is of an essentially different and infinitely more intensive kind than all Hindostan had to suffer before. England has broken down the entire framework of Indian society, without any symptoms of reconstitution yet appearing... [however], we must not forget that these idyllic village communities, inoffensive though they may appear, had always been the solid foundation of Oriental despotism, that they restrained the human mind within the smallest possible compass, making it the unresisting tool of superstition.[263][265]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Marx's ideas have had a profound impact on world politics and intellectual thought,[6][7][266][267] in particular in the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution.[268] Followers of Marx have often debated among themselves over how to interpret Marx's writings and apply his concepts to the modern world.[269] The legacy of Marx's thought has become contested between numerous tendencies, each of which sees itself as Marx's most accurate interpreter. In the political realm, these tendencies include political theories such as Leninism, Marxism–Leninism, Trotskyism, Maoism, Luxemburgism, libertarian Marxism,[269] and Open Marxism. Various currents have also developed in academic Marxism, often under influence of other views, resulting in structuralist Marxism, historical materialism, phenomenological Marxism, analytical Marxism, and Hegelian Marxism.[269]