Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Old East Slavic

Slavic language used in the 10th–15th centuries From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Old East Slavic[a] (traditionally also Old Russian) was a language (or a group of dialects) used by the East Slavs from the 7th or 8th century to the 13th or 14th century,[4] until it diverged into the Russian and Ruthenian languages.[5] Ruthenian eventually evolved into the Belarusian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian languages.[6]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

Remove ads

Terminology

Summarize

Perspective

The term Old East Slavic is used in reference to the modern family of East Slavic languages. However, it is not universally applied.[7] The language is also traditionally known as Old Russian;[8][9][10][11] however, the term may be viewed as anachronistic, because the initial stages of the language which it denotes predate the dialectal divisions marking the nascent distinction between modern East Slavic languages,[12] therefore a number of authors have proposed using Old East Slavic (or Common East Slavic) as a more appropriate term.[13][14][15] Old Russian is also used to describe the written language in Russia until the 18th century,[16] when it became Modern Russian, though the early stages of the language is often called Old East Slavic instead;[17] the period after the common language of the East Slavs is sometimes distinguished as Middle Russian,[18] or Great Russian.[19]

Some scholars have also called the language Old Rus'ian[20] or Old Rusan,[21] Rusian, or simply Rus,[22][23] although these are the least commonly used forms.[24]

Ukrainian-American linguist George Shevelov used the term Common Russian or Common Eastern Slavic to refer to the hypothetical uniform language of the East Slavs.[25]

American Slavist Alexander M. Schenker pointed out that modern terms for the medieval language of the East Slavs varied depending on the political context.[26] He suggested using the neutral term East Slavic for that language.[27]

Remove ads

Phonology

Vowels

Note that there were also iotated variants: ꙗ, ѥ, ю, ѩ, ѭ.

By the 13th century, ь and ъ either became silent or merged with е and о, and ѧ and ѫ had merged with ꙗ and у respectively.

Consonants

Old East Slavic retains all the consonants of Proto-Slavic, with the exception of ť and ď which merged into č and ž respectively. After the 11th century, all consonants become palatalized before front vowels.

Remove ads

General considerations

Summarize

Perspective

The language was a descendant of the Proto-Slavic language and retained many of its features. It developed so-called pleophony (or polnoglasie 'full vocalisation'), which came to differentiate the newly evolving East Slavic from other Slavic dialects. For instance, Common Slavic *gȏrdъ 'settlement, town' was reflected as OESl. gorodъ,[28] Common Slavic *melkò 'milk' > OESl. moloko,[29] and Common Slavic *kòrva 'cow' > OESl korova.[30] Other Slavic dialects differed by resolving the closed-syllable clusters *eRC and *aRC as liquid metathesis (South Slavic and West Slavic), or by no change at all (see the article on Slavic liquid metathesis and pleophony for a detailed account).

Since extant written records of the language are sparse, it is difficult to assess the level of its unity. In consideration of the number of tribes and clans that constituted Kievan Rus', it is probable that there were many dialects of Old East Slavonic. Therefore, today we may speak definitively only of the languages of surviving manuscripts, which, according to some interpretations, show regional divergence from the beginning of the historical records. By c. 1150, it had the weakest local variations among the four regional macrodialects of Common Slavic, c. 800 – c. 1000, which had just begun to differentiate into its branches.[31]

With time, it evolved into several more diversified forms; following the fragmentation of Kievan Rus' after 1100, dialectal differentiation accelerated.[32] The regional languages were distinguishable starting in the 12th or 13th century.[33] Thus different variations evolved of the Russian language in the regions of Novgorod, Moscow, South Russia and meanwhile the Ukrainian language was also formed. Each of these languages preserves much of the Old East Slavic grammar and vocabulary. The Russian language in particular borrows more words from Church Slavonic than does Ukrainian.[34]

However, findings by Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak suggest that, until the 14th or 15th century, major language differences were not between the regions occupied by modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine,[35] but rather between the north-west (around modern Velikiy Novgorod and Pskov) and the center (around modern Kyiv, Suzdal, Rostov, Moscow as well as Belarus) of the East Slavic territories.[36] The Old Novgorodian dialect of that time differed from the central East Slavic dialects as well as from all other Slavic languages much more than in later centuries.[37][38] According to Zaliznyak, the Russian language developed as a convergence of that dialect and the central ones,[39] whereas Ukrainian and Belarusian were continuation of development of the central dialects of the East Slavs.[40]

Also, Russian linguist Sergey Nikolaev, analysing historical development of Slavic dialects' accent system, concluded that a number of other tribes in Kievan Rus' came from different Slavic branches and spoke distant Slavic dialects.[41][page needed]

Another Russian linguist, G. A. Khaburgaev,[42] as well as a number of Ukrainian linguists (Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Ivan Ohienko, George Shevelov, Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo), deny the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past.[43] According to them, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages.[44]

Following the end of the "Tatar yoke", the territory of former Kievan Rus' was divided between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow,[45] and two separate literary traditions emerged in these states, Ruthenian in the west and medieval Russian in the east.[46][47][48]

Remove ads

Literary language

Summarize

Perspective

The political unification of the region into the state called Kievan Rus', from which modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine trace their origins, occurred approximately a century before the adoption of Christianity in 988 and the establishment of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and literary language. Documentation of the Old East Slavic language of this period is scanty, making it difficult at best fully to determine the relationship between the literary language and its spoken dialects.

There are references in Byzantine sources to pre-Christian Slavs in European Russia using some form of writing. Despite some suggestive archaeological finds and a corroboration by the tenth-century monk Chernorizets Hrabar that ancient Slavs wrote in "strokes and incisions", the exact nature of this system is unknown.

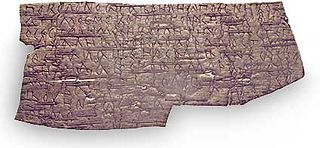

Although the Glagolitic alphabet was briefly introduced, as witnessed by church inscriptions in Novgorod, it was soon entirely superseded by Cyrillic.[49][citation needed] The samples of birch-bark writing excavated in Novgorod have provided crucial information about the pure tenth-century vernacular in North-West Russia, almost entirely free of Church Slavonic influence. It is also known that borrowings and calques from Byzantine Greek began to enter the vernacular at this time, and that simultaneously the literary language in its turn began to be modified towards Eastern Slavic.

The following excerpts illustrate two of the most famous literary monuments.

NOTE: The spelling of the original excerpt has been partly modernized. The translations are best attempts at being literal, not literary.

Primary Chronicle

c. 1110, from the Laurentian Codex, 1377:

In this usage example of the language, the fall of the yers is in progress or arguably complete: several words end with a consonant, e.g. кнѧжит, knęžit "to rule" < кънѧжити, kǔnęžiti (modern Uk княжити, knjažyty, R княжить, knjažit', B княжыць, knjažyc'). South Slavic features include времѧньнъıх, vremęnǐnyx "bygone" (modern R минувших, minuvšix, Uk минулих, mynulyx, B мінулых, minulyx). Correct use of perfect and aorist: єсть пошла, estǐ pošla "is/has come" (modern B пайшла, pajšla, R пошла, pošla, Uk пішла, pišla), нача, nača "began" (modern Uk почав, počav, B пачаў, pačaŭ, R начал, načal) as a development of the old perfect. Note the style of punctuation.

The Tale of Igor's Campaign

Слово о пълку Игоревѣ. c. 1200, from the Pskov manuscript, fifteenth cent.

Illustrates the sung epics, with typical use of metaphor and simile.

It has been suggested that the phrase растекаться мыслью по древу (rastekat'sja mysl'ju po drevu, to run in thought upon/over wood), which has become proverbial in modern Russian with the meaning "to speak ornately, at length, excessively," is a misreading of an original мысію, mysiju (akin to мышь "mouse") from "run like a squirrel/mouse on a tree"; however, the reading мыслью, myslǐju is present in both the manuscript copy of 1790 and the first edition of 1800, and in all subsequent scholarly editions.

Remove ads

Old East Slavic literature

Summarize

Perspective

The Old East Slavic language developed a certain literature of its own, though much of it (in hand with those of the Slavic languages that were, after all, written down) was influenced as regards style and vocabulary by religious texts written in Church Slavonic.[58] Surviving literary monuments include the legal code Russkaya Pravda, a corpus of hagiography and homily, The Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the earliest surviving manuscript of the Primary Chronicle – the Laurentian Codex of 1377.[59]

The earliest dated specimen of Old East Slavic (or, rather, of Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference) must be considered the written Sermon on Law and Grace by Hilarion, metropolitan of Kiev.[60] In this work there is a panegyric on Prince Vladimir of Kiev, the hero of so much of East Slavic popular poetry.[61] It is rivalled by another panegyric on Vladimir, written a decade later by Yakov the Monk.[62]

Other 11th-century writers are Theodosius, a monk of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, who wrote on the Latin faith and some Pouchenia or Instructions, and Luka Zhidiata, bishop of Novgorod, who has left a curious Discourse to the Brethren. [63] From the writings of Theodosius we see that many pagan habits were still in vogue among the people. He finds fault with them for allowing these to continue, and also for their drunkenness; nor do the monks escape his censures.[64] Zhidiata writes in a more vernacular style than many of his contemporaries; he eschews the declamatory tone of the Byzantine authors.[65] And here may be mentioned the many lives of the saints and the Fathers to be found in early East Slavic literature, starting with the two Lives of Sts Boris and Gleb, written in the late eleventh century and attributed to Jacob the Monk and to Nestor the Chronicler.[66]

With the so-called Primary Chronicle, also attributed to Nestor, begins the long series of the Russian annalists.[67] There is a regular catena of these chronicles, extending with only two breaks to the seventeenth century.[68] Besides the work attributed to Nestor the Chronicler, there are the chronicles of Novgorod, Kiev, Volhynia and many others. Every town of any importance could boast of its annalists, Pskov and Suzdal among others.[69]

In the 12th century, we have the sermons of Bishop Cyril of Turov, which are attempts to imitate in Old East Slavic the florid Byzantine style.[70] In his sermon on Holy Week, Christianity is represented under the form of spring, Paganism and Judaism under that of winter, and evil thoughts are spoken of as boisterous winds.[71]

There are also the works of early travellers, as the igumen Daniel, who visited the Holy Land at the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century. [72] A later traveller was Afanasiy Nikitin, a merchant of Tver, who visited India in 1470. He has left a record of his adventures, which has been translated into English and published for the Hakluyt Society.[73][74]

A curious monument of old Slavonic times is the Pouchenie (“Instruction”), written by Vladimir Monomakh for the benefit of his sons. [75] This composition is generally found inserted in the Chronicle of Nestor; it gives a fine picture of the daily life of a Slavonic prince.[76] The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery is a typical medieval collection of stories from the life of monks, featuring devils, angels, ghosts, and miraculous resurrections.[77][78]

Lay of Igor's Campaign narrates the expedition of Igor Svyatoslavich, the prince of Novgorod-Seversk, against the Cumans.[79] It is neither epic nor a poem but is written in rhythmic prose. An interesting aspect of the text is its mix of Christianity and ancient Slavic religion. Igor's wife Yaroslavna famously invokes natural forces from the walls of Putyvl. Christian motifs present along with depersonalised pagan gods in the form of artistic images.[80] Another aspect, which sets the book apart from contemporary Western epics, are its numerous and vivid descriptions of nature, and the role which nature plays in human lives. Of the whole bulk of the Old East Slavic literature, the Lay is the only work familiar to every educated Russian or Ukrainian. Its brooding flow of images, murky metaphors, and ever-changing rhythm have not been successfully rendered into English yet. Indeed, the meanings of many words found in it have not been satisfactorily explained by scholars.[81]

The Zadonshchina is a sort of prose poem much in the style of The Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the resemblance of the latter to this piece furnishes an additional proof of its genuineness.[82] This account of the Battle of Kulikovo, which was gained by Dmitry Donskoy over the Mongols in 1380, has come down in three important versions.[83][84]

The early laws of Rus' present many features of interest, such as the Russkaya Pravda of Yaroslav the Wise, which is preserved in the chronicle of Novgorod; the date is between 1018 and 1072. [85] [86] [87]

Remove ads

Study

The earliest attempts to compile a comprehensive lexicon of Old East Slavic were undertaken by Alexander Vostokov and Izmail Sreznevsky in the nineteenth century.[88] Sreznevsky's Materials for the Dictionary of the Old Russian Language on the Basis of Written Records (1893–1903), though incomplete, remained a standard reference until the appearance of a 24-volume academic dictionary in 1975–99.[89][90]

Remove ads

Notable texts

- Bylinas

- The Tale of Igor's Campaign – the most outstanding literary work in this language

- Russkaya Pravda – an eleventh-century legal code issued by Yaroslav the Wise

- Praying of Daniel the Immured

- A Journey Beyond the Three Seas

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

General references

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads