Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

International Phonetic Alphabet

System of phonetic notation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

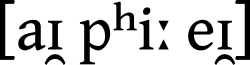

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standard written representation for the sounds of speech.[1] The IPA is used by linguists, lexicographers, foreign language students and teachers, speech–language pathologists, singers, actors, constructed language creators, and translators.[2][3]

The IPA is designed to represent those qualities of speech that are part of lexical (and, to a limited extent, prosodic) sounds in spoken (oral) language: phones, intonation and the separation of syllables.[1] To represent additional qualities of speech – such as tooth gnashing, lisping, and sounds made with a cleft palate – an extended set of symbols may be used.[2]

Segments are transcribed by one or more IPA symbols of two basic types: letters and diacritics. For example, the sound of the English letter ⟨t⟩ may be transcribed in IPA with a single letter: [t], or with a letter plus diacritics: [t̺ʰ], depending on how precise one wishes to be. Similarly, the French letter ⟨t⟩ may be transcribed as either [t] or [t̻]: [t̺ʰ] and [t̻] are two different, though similar, sounds. Slashes are used to signal phonemic transcription; therefore, /t/ is more abstract than either [t̺ʰ] or [t̻] and might refer to either, depending on the context and language.[note 1]

Occasionally, letters or diacritics are added, removed, or modified by the International Phonetic Association. As of the most recent change in 2005,[4] there are 107 segmental letters, an indefinitely large number of suprasegmental letters, 44 diacritics (not counting composites), and four extra-lexical prosodic marks in the IPA. These are illustrated in the current IPA chart, posted below in this article and on the International Phonetic Association's website.[5]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1886 a group of French and English language teachers, led by the French linguist Paul Passy, formed what would be known from 1897 onwards as the International Phonetic Association (in French, l'Association phonétique internationale).[6] The idea of the alphabet had been suggested to Passy by Otto Jespersen. It was developed by Passy along with other members of the association, principally Daniel Jones. The original IPA alphabet was based on the Romic alphabet, an English spelling reform created by Henry Sweet that in turn was based on the Palaeotype alphabet of Alexander John Ellis, itself derived from Lepsius Standard Alphabet first used for transcribing Ancient Egyptian into German.

The original intent was to make it usable for other languages the values of the symbols were allowed to vary from language to language.[note 2] For example, the sound [ʃ] (the sh in shoe) was originally represented with the letter ⟨c⟩ for English but with ⟨x⟩ for French and German; with German, ⟨c⟩ was used for the [x] sound of Bach.[6] With a growing number of transcribed languages this proved impractical, and in 1888 the values of the letters were made uniform across languages. This would provide the base for all future revisions.[6][8]

Since its creation, the IPA has undergone a number of revisions. After relatively frequent revisions and expansions from the 1890s to the 1940s, the IPA remained nearly static until the Kiel Convention in 1989, which substantially revamped the alphabet. A smaller revision took place in 1993 with the resurrection of letters for mid central vowels[2] and the retirement of letters for voiceless implosives.[9] The alphabet was last revised in May 2005 with the addition of a letter for a labiodental flap.[10] Apart from the addition and removal of symbols, changes to the IPA have consisted largely of renaming symbols and categories and in modifying typefaces.[2]

Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for speech pathology (extIPA) were created in 1990 and were officially adopted by the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association in 1994.[11] They were substantially revised in 2015 with lesser changes in 2025.

Remove ads

Description

Summarize

Perspective

The general principle of the IPA is to provide one letter for each distinctive sound (phoneme).[note 3] This means that:

- It does not use combinations of letters to represent single sounds, the way English does with ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩ and ⟨ng⟩, nor single letters to represent multiple sounds, the way ⟨x⟩ represents /ks/ or /ɡz/ in English.[note 4]

- There are no letters that have context-dependent sound values, the way ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ in several European languages have a "hard" or "soft" pronunciation.

- The IPA does not generally have separate letters for two sounds if no known language makes a distinction between them, a property known as "selectiveness".[2][note 5] However, if a large number of phonemically distinct letters can be derived with a diacritic, that may be used instead.[note 6]

The alphabet is designed for transcribing sounds (phones), not phonemes, though it is used for phonemic transcription as well. A few letters that did not indicate specific sounds have been retired – ⟨ˇ⟩, once used for the "compound" tone of Swedish and Norwegian, and ⟨ƞ⟩, once used for the moraic nasal of Japanese – though one remains: ⟨ɧ⟩, used for the sj-sound of Swedish. When the IPA is used for broad phonetic or for phonemic transcription, the letter–sound correspondence can be rather loose. The IPA has recommended that more 'familiar' letters be used when that would not cause ambiguity.[13] For example, ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ for [ɛ] and [ɔ], ⟨t⟩ for [t̪] or [ʈ], ⟨f⟩ for [ɸ], etc. Indeed, in the illustration of Hindi in the IPA Handbook, the letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are used for /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/.

Among the symbols of the IPA, 107 letters represent consonants and vowels, 31 diacritics are used to modify these, and 17 additional signs indicate suprasegmental qualities such as length, tone, stress, and intonation.[note 7] These are organized into a chart; the chart displayed here is the official chart as posted at the website of the IPA.

Letter forms

The International Phonetic Alphabet is based on the Latin script, and uses as few non-Latin letters as possible.[6] The non-Latin letters are meant to harmonize with the Latin letters.[note 8] For this reason, most letters are either Latin, Greek, or modifications thereof. Some letters are neither: for example, the letter denoting the glottal stop, ⟨ʔ⟩, originally had the form of a question mark with the dot removed. A few letters, such as that of the voiced pharyngeal fricative, ⟨ʕ⟩, were inspired by other writing systems (in this case, the Arabic letter ⟨ﻉ⟩, ʿayn, via the reversed apostrophe).[9]

The Association created the IPA so that the sound values of most letters would correspond to "international usage" (approximately Classical Latin).[6] Hence, the consonant letters ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨ɡ⟩, ⟨h⟩, ⟨k⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨s⟩, ⟨t⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨w⟩, and ⟨z⟩ have more or less their word-initial values in English (g as in gill, h as in hill, though p t k are unaspirated as in spill, still, skill); and the vowel letters ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ correspond to the (long) sound values of Latin: [i] is like the vowel in machine, [u] is as in rule, etc. Other Latin letters, particularly ⟨j⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨y⟩, differ from English, but have their IPA values in Latin or other European languages.

Beyond the letters themselves, there are a variety of secondary symbols which aid in transcription. Diacritic marks can be combined with the letters to add tone and phonetic detail such as secondary articulation. There are also special symbols for prosodic features such as stress and intonation.

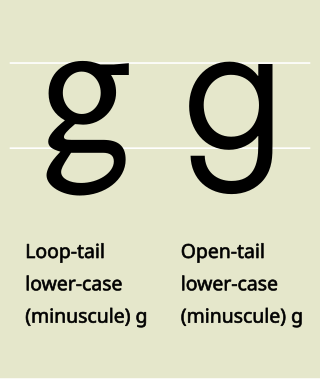

Typography

The basic Latin inventory was extended by adding small-capital and cursive forms, overlapping diacritics such as hooks, and rotation. The sound values of these letters are related to those of the original letters or to those of letters that they were modified to resemble.[note 9] For example, rotated letters were popular in the era of mechanical typesetting, as they had the advantage of not requiring the casting of special type for IPA symbols, much as the sorts for ⟨b⟩ and ⟨q⟩, ⟨d⟩ and ⟨p⟩, ⟨n⟩ and ⟨u⟩, and ⟨6⟩ and ⟨9⟩ had traditionally often pulled double duty to reduce printers' costs.[citation needed] Thus rotated ⟨ɐ ə ɹ ʍ⟩ recall a e r w, while rotated ⟨ɔ ɟ ɓ ɥ ɯ ʌ ʎ⟩ recall o j b y u/w ᴀ y/λ.[note 10]

There are several letters from the Greek alphabet, though their sound values may differ from Greek. For most Greek letters, subtly different glyph shapes have been devised for the IPA, specifically ⟨ꞵ⟩, ⟨ɣ⟩, ⟨ɛ⟩, ⟨ɸ⟩, ⟨ꭓ⟩ and ⟨ʋ⟩, which are encoded in Unicode separately from their parent Greek letters. One, however – ⟨θ⟩ – has only its Greek form, while for ⟨ꞵ ~ β⟩ and ⟨ꭓ ~ χ⟩, both Greek and Latin forms are in common use.[16]

Iconicity

The graphic derivation of letters and diacritics may be iconic

- A rightward-facing hooked tail, as in ⟨ʈ ɖ ɳ ɽ ʂ ʐ ɻ ɭ ⟩, indicates retroflex articulation. It originates from the hooked arm of an r.

- The top hook, as in ⟨ɠ ɗ ɓ⟩, indicates implosion.

- Several nasal consonants are based on the form ⟨n⟩: ⟨n ɲ ɳ ŋ⟩. ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ŋ⟩ derive from ligatures of gn and ng, and ⟨ɱ⟩ is an ad hoc imitation of ⟨ŋ⟩.

- Among consonant letters, the small capital letters ⟨ɢ ʜ ʟ ɴ ʀ ʁ⟩, and also ⟨ꞯ⟩ in extIPA, indicate more guttural sounds than their base letters – ⟨ʙ⟩ is a late exception. Among vowel letters, the small capitals ⟨ɪ ʏ ʊ⟩ indicate what had originally been considered more lax articulations than their base letters; ⟨ʊ⟩ had originally been ⟨ᴜ⟩.[17] Again, small-cap ⟨ɶ⟩ is a late exception.

- The tone letters derive from a pitch trace on a musical scale.

Brackets and transcription delimiters

There are two principal types of brackets used to set off (delimit) IPA transcriptions:

Less common conventions include:

All three of the above are provided by the IPA Handbook. The following are not, but may be seen in IPA transcription or in associated material (especially angle brackets):

Some examples of contrasting brackets in the literature:

In some English accents, the phoneme /l/, which is usually spelled as ⟨l⟩ or ⟨ll⟩, is articulated as two distinct allophones: the clear [l] occurs before vowels and the consonant /j/, whereas the dark [ɫ]/[lˠ] occurs before consonants, except /j/, and at the end of words.[32]

the alternations /f/ – /v/ in plural formation in one class of nouns, as in knife /naɪf/ – knives /naɪvz/, which can be represented morphophonemically as {naɪV} – {naɪV+z}. The morphophoneme {V} stands for the phoneme set {/f/, /v/}.[33]

[ˈf\faɪnəlz ˈhɛld ɪn (.) ⸨knock on door⸩ bɑɹsə{𝑝ˈloʊnə and ˈmədɹɪd 𝑝}] — f-finals held in Barcelona and Madrid.[34]

Other representations

IPA letters have cursive forms designed for use in manuscripts and when taking field notes, but the Handbook recommended against their use, as cursive IPA is "harder for most people to decipher".[35] A braille representation of the IPA for blind or visually impaired professionals and students has also been developed.[36]

Remove ads

Modifying the IPA chart

Summarize

Perspective

The International Phonetic Alphabet is occasionally modified by the Association. After each modification, the Association provides an updated simplified presentation of the alphabet in the form of a chart. (See History of the IPA.) Not all aspects of the alphabet can be accommodated in a chart of the size published by the IPA. The alveolo-palatal and epiglottal consonants, for example, are not included in the consonant chart for reasons of space rather than of theory (two additional columns would be required, one between the retroflex and palatal columns and the other between the pharyngeal and glottal columns), and the lateral flap would require an additional row for that single consonant, so they are listed instead under the catchall block of "other symbols".[37] The indefinitely large number of tone letters would make a full accounting impractical even on a larger page, and only a few examples are shown, and even the tone diacritics are not complete; the reversed tone letters are not illustrated at all.

The procedure for modifying the alphabet or the chart is to propose the change in the Journal of the IPA. (See, for example, December 2008 on an open central unrounded vowel[38] and August 2011 on central approximants.)[39] Reactions to the proposal may be published in the same or subsequent issues of the Journal (as in August 2009 on the open central vowel).[40][better source needed] A formal proposal is then put to the Council of the IPA[41][clarification needed] – which is elected by the membership[42] – for further discussion and a formal vote.[43][44]

Many users of the alphabet, including the leadership of the Association itself, deviate from its standardized usage.[45] The Journal of the IPA finds it acceptable to mix IPA and extIPA symbols in consonant charts in their articles. (For instance, including the extIPA letter ⟨𝼆⟩, rather than ⟨ʎ̝̊⟩, in an illustration of the IPA.)[46]

Remove ads

Usage

Summarize

Perspective

Of more than 160 IPA symbols, relatively few will be used to transcribe speech in any one language, with various levels of precision. A precise phonetic transcription, in which sounds are specified in detail, is known as a narrow transcription. A coarser transcription with less detail is called a broad transcription. Both are relative terms, and both are generally enclosed in square brackets.[1] Broad phonetic transcriptions may restrict themselves to easily heard details, or only to details that are relevant to the discussion at hand, and may differ little if at all from phonemic transcriptions, but they make no theoretical claim that all the distinctions transcribed are necessarily meaningful in the language. The term 'broad' may furthermore carry implication that diacritics are avoided (at least as far as possible) or even that the transcription is restricted to the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet.[47]

For example, the English word little may be transcribed broadly as [ˈlɪtəl], approximately describing many pronunciations. A narrower transcription may focus on individual or dialectical details: [ˈɫɪɾɫ] in General American, [ˈlɪʔo] in Cockney, or [ˈɫɪːɫ] in Southern US English.

Phonemic transcriptions, which express the conceptual counterparts of spoken sounds, are usually enclosed in slashes (/ /) and tend to use simpler letters with few diacritics. The choice of IPA letters may reflect theoretical claims of how speakers conceptualize sounds as phonemes or they may be merely a convenience for typesetting. Phonemic approximations between slashes do not have absolute sound values. For instance, in English, either the vowel of pick or the vowel of peak may be transcribed as /i/, so that pick, peak would be transcribed as /ˈpik, ˈpiːk/ or as /ˈpɪk, ˈpik/; and neither is identical to the vowel of the French pique, which would also be transcribed /pik/. By contrast, a narrow phonetic transcription of pick, peak, pique could be: [pʰɪk], [pʰiːk], [pikʲ].

Linguists

IPA is popular for transcription by linguists. Some American linguists, however, use a mix of IPA with Americanist phonetic notation or Sinological phonetic notation or otherwise use nonstandard symbols for various reasons.[48] Authors who employ such nonstandard use are encouraged to include a chart or other explanation of their choices, which is good practice in general, as linguists differ in their understanding of the exact meaning of IPA symbols and common conventions change over time.

Dictionaries

English

Many British dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary and some learner's dictionaries such as the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary and the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, now use the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent the pronunciation of words.[49] However, most American (and some British) volumes use one of a variety of pronunciation respelling systems, intended to be more comfortable for readers of English and to be more acceptable across dialects, without the implication of a preferred pronunciation that the IPA might convey. For example, the respelling systems in many American dictionaries (such as Merriam-Webster) use ⟨y⟩ for IPA [ j] and ⟨sh⟩ for IPA [ ʃ ], reflecting the usual spelling of those sounds in English.[50][51][note 14] (In IPA, [y] represents the sound of the French ⟨u⟩, as in tu, and [sh] represents the sequence of consonants in grasshopper.)

Other languages

The IPA is also not universal among dictionaries in languages other than English. Monolingual dictionaries of languages with phonemic orthographies generally do not bother with indicating the pronunciation of most words, and tend to use respelling systems for words with unexpected pronunciations. Dictionaries produced in Israel use the IPA rarely and sometimes use the Hebrew alphabet for transcription of foreign words.[note 15] Bilingual dictionaries that translate from foreign languages into Russian usually employ the IPA, but monolingual Russian dictionaries occasionally use pronunciation respelling for foreign words.[note 16] The IPA is more common in bilingual dictionaries, but there are exceptions here too. Mass-market bilingual Czech dictionaries, for instance, tend to use the IPA only for sounds not found in Czech.[note 17]

Standard orthographies and case variants

IPA letters have been incorporated into the alphabets of various languages, notably via the Africa Alphabet in many sub-Saharan languages such as Hausa, Fula, Akan, Gbe languages, Manding languages, Lingala, etc. Capital case variants have been created for use in these languages. For example, Kabiyè of northern Togo has Ɖ ɖ, Ŋ ŋ, Ɣ ɣ, Ɔ ɔ, Ɛ ɛ, Ʋ ʋ. These, and others, are supported by Unicode, but appear in Latin ranges other than the IPA extensions.

In the IPA itself, however, only lower-case letters are used. The 1949 edition of the IPA handbook indicated that an asterisk ⟨*⟩ might be prefixed to indicate that a word was a proper name,[53] and this convention was used by Le Maître Phonétique, which was written in IPA rather than in English or French orthography, but it was not included in the 1999 Handbook, which notes the contrary use of the asterisk as a placeholder for a sound or feature that does not have a symbol.[54]

Classical singing

The IPA has widespread use among classical singers during preparation as they are frequently required to sing in a variety of foreign languages. They are also taught by vocal coaches to perfect diction and improve tone quality and tuning.[55] Opera librettos are authoritatively transcribed in IPA, such as Nico Castel's volumes[56] and Timothy Cheek's book Singing in Czech.[57] Opera singers' ability to read IPA was used by the site Visual Thesaurus, which employed several opera singers "to make recordings for the 150,000 words and phrases in VT's lexical database ... for their vocal stamina, attention to the details of enunciation, and most of all, knowledge of IPA".[58]

Remove ads

Letters

Summarize

Perspective

The International Phonetic Association organizes the letters of the IPA into three categories: pulmonic consonants, non-pulmonic consonants, and vowels.[note 18][60][61]

Pulmonic consonant letters are arranged singly or in pairs of voiceless (tenuis) and voiced sounds, with these then grouped in columns from front (labial) sounds on the left to back (glottal) sounds on the right. In official publications by the IPA, two columns are omitted to save space, with the letters listed among "other symbols" even though theoretically they belong in the main chart.[note 19] They are arranged in rows from full closure (occlusives: stops and nasals) at top, to brief closure (vibrants: trills and taps), to partial closure (fricatives), and finally minimal closure (approximants) at bottom, again with a row left out to save space. In the table below, a slightly different arrangement is made: All pulmonic consonants are included in the pulmonic-consonant table, and the vibrants and laterals are separated out so that the rows reflect the common lenition pathway of stop → fricative → approximant, as well as the fact that several letters pull double duty as both fricative and approximant; affricates may then be created by joining stops and fricatives from adjacent cells. Shaded cells represent articulations that are judged to be impossible or not distinctive.

Vowel letters are also grouped in pairs – of unrounded and rounded vowel sounds – with these pairs also arranged from front on the left to back on the right, and from maximal closure at top to minimal closure at bottom. No vowel letters are omitted from the chart, though in the past some of the mid central vowels were listed among the "other symbols".

Consonants

Pulmonic consonants

A pulmonic consonant is a consonant made by obstructing the glottis (the space between the vocal folds) or oral cavity (the mouth) and either simultaneously or subsequently letting out air from the lungs. Pulmonic consonants make up the majority of consonants in the IPA, as well as in human language. All consonants in English fall into this category.[63]

The pulmonic consonant table, which includes most consonants, is arranged in rows that designate manner of articulation, meaning how the consonant is produced, and columns that designate place of articulation, meaning where in the vocal tract the consonant is produced. The main chart includes only consonants with a single place of articulation.

Notes

- In rows where some letters appear in pairs (the obstruents), the letter to the right represents a voiced consonant, except breathy-voiced [ɦ].[64] In the other rows (the sonorants), the single letter represents a voiced consonant.

- While IPA provides a single letter for the coronal places of articulation (for all consonants but fricatives), these do not always have to be used exactly. When dealing with a particular language, the letters may be treated as specifically dental, alveolar, or post-alveolar, as appropriate for that language, without diacritics.

- Shaded areas indicate articulations judged to be impossible.

- The letters [β, ð, ʁ, ʕ, ʢ] are canonically voiced fricatives but may be used for approximants.[note 20]

- In many languages, such as English, [h] and [ɦ] are not actually glottal, fricatives, or approximants. Rather, they are bare phonation.[66]

- It is primarily the shape of the tongue rather than its position that distinguishes the fricatives [ʃ ʒ], [ɕ ʑ], and [ʂ ʐ].

- [ʜ, ʢ] are defined as epiglottal fricatives under the "Other symbols" section in the official IPA chart, but they may be treated as trills at the same place of articulation as [ħ, ʕ] because trilling of the aryepiglottic folds typically co-occurs.[67]

- Some listed phones are not known to exist as phonemes in any language.

Non-pulmonic consonants

Non-pulmonic consonants are sounds whose airflow is not dependent on the lungs. These include clicks (found in the Khoisan languages and some neighboring Bantu languages of Africa), implosives (found in languages such as Sindhi, Hausa, Swahili and Vietnamese), and ejectives (found in many Amerindian and Caucasian languages).

Notes

- Clicks have traditionally been described as consisting of a forward place of articulation, commonly called the click "type" or historically the "influx", and a rear place of articulation, which when combined with the quality of the click is commonly called the click "accompaniment" or historically the "efflux". The IPA click letters indicate only the click type (forward articulation and release). Therefore, all clicks require two letters for proper notation: ⟨k͡ǀ, ɡ͡ǀ, q͡ǀ⟩, etc., or with the order reversed if both the forward and rear releases are audible. The letter for the rear articulation is frequently omitted, in which case a ⟨k⟩ may usually be assumed. However, some researchers dispute the idea that clicks should be analyzed as doubly articulated, as the traditional transcription implies, and analyze the rear occlusion as solely a part of the airstream mechanism.[68] In transcriptions of such approaches, the click letter represents both places of articulation, with the different letters representing the different click types, and diacritics are used for the elements of the accompaniment: ⟨ǀ, ǀ̬, ǀ̃⟩, etc.

- Letters for the voiceless implosives ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ are no longer supported by the IPA, though they remain in Unicode. Instead, the IPA typically uses the voiced equivalent with a voiceless diacritic: ⟨ɓ̥, ɗ̥⟩, etc.

- The letter for the retroflex implosive, ⟨ᶑ ⟩, is not "explicitly IPA approved",[69] but the IPA has endorsed the inclusion of ⟨ᶑ ⟩ and voiceless ⟨𝼉⟩ into Unicode.[citation needed]

- The ejective diacritic is placed at the right-hand margin of the consonant, rather than immediately after the letter for the stop: ⟨t͜ʃʼ⟩, ⟨kʷʼ⟩. In imprecise transcription, it often stands in for a superscript glottal stop in glottalized but pulmonic sonorants, such as [mˀ], [lˀ], [wˀ], [aˀ] – also transcribable as creaky [m̰], [l̰], [w̰], [a̰].

Affricates

Affricates and co-articulated stops are represented by two letters in sequence. For clarity, this digraph may be joined by a tie bar, which may appear either above or below the letters with no difference in meaning.[note 21] Affricates are optionally represented by ligatures – e.g. ⟨ʧ, ʤ ⟩ – though this is no longer official IPA usage.[1] Alternatively, a superscript notation for a consonant release is sometimes used to transcribe affricates, for example ⟨tˢ⟩ for [t͜s], although in precise notation this would indicate a fricative release rather than an affricate. The letters for the palatal plosives ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are often used as a convenience for [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ] or similar affricates, even in official IPA publications, so they must be interpreted with care.[71]

Because in a true affricate the plosive element and the fricative element are homorganic, and the place of articulation of an affricate is most audible in the fricative element, the letter for the former will not always be precisely transcribed where such precision would be redundant. For example, while the English ch sound is [t̠͡ʃ] in close transcription, the diacritic is commonly left off, for [t͡ʃ]. Similarly, [ʈ͡ʂ] and [ɖ͡ʐ] are more commonly written [t͡ʂ] and [d͡ʐ], and in the ligatures there is only a single retroflex hook.

Co-articulated consonants

Co-articulated consonants are sounds that involve two simultaneous places of articulation (are pronounced using two parts of the vocal tract). In English, the [w] in "went" is a coarticulated consonant, being pronounced by rounding the lips and raising the back of the tongue. Similar sounds are [ʍ] and [ɥ]. In some languages, plosives can be double-articulated, for example in the name of Laurent Gbagbo.

|

|

Notes

- [ɧ], the Swedish sj-sound, is described by the IPA as a "simultaneous [ʃ] and [x]", but it is unlikely such a simultaneous fricative actually exists in any language.[72]

- Multiple tie bars can be used: ⟨a͡b͡c⟩ or ⟨a͜b͜c⟩. For instance, a pre-voiced velar affricate may be transcribed as ⟨g͡k͡x⟩

- If a diacritic needs to be placed on or under a tie bar, the combining grapheme joiner (U+034F) needs to be used, as in [b͜͏̰də̀bdʊ̀] 'chewed' (Margi). Font support is spotty, however.

With the implosives, authors may not bother to redundantly mark both letters as implosive, but instead write them as less-cluttered ⟨ɡ͡ɓ⟩ and even ⟨k͜ƥ⟩.

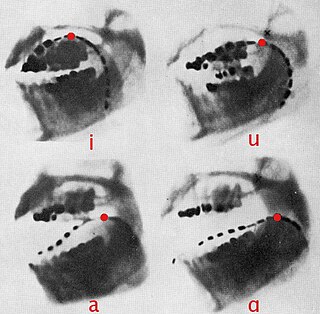

Vowels

The IPA defines a vowel as a sound which occurs at a syllable center.[73] Below is a chart depicting the vowels of the IPA. The IPA maps the vowels according to the position of the tongue.

The vertical axis of the chart is mapped by vowel height. Vowels pronounced with the tongue lowered are at the bottom, and vowels pronounced with the tongue raised are at the top. For example, [ɑ] (the first vowel in father) is at the bottom because the tongue is lowered in this position. [i] (the vowel in "meet") is at the top because the sound is said with the tongue raised to the roof of the mouth.

In a similar fashion, the horizontal axis of the chart is determined by vowel backness. Vowels with the tongue moved towards the front of the mouth (such as [ɛ], the vowel in "met") are to the left in the chart, while those in which it is moved to the back (such as [ʌ], the vowel in "but") are placed to the right in the chart.

In places where vowels are paired, the right represents a rounded vowel (in which the lips are rounded) while the left is its unrounded counterpart.

Diphthongs

Diphthongs may be written as simple sequences of letters, but for clarity they are commonly specified with a non-syllabic diacritic, as in ⟨ui̯⟩ or ⟨u̯i⟩, or with a superscript for the on- or off-glide, as in ⟨uⁱ⟩ or ⟨ᵘi⟩. Sometimes a tie bar is used: ⟨u͜i⟩, especially when it is difficult to tell if the diphthong is characterized by an on-glide or an off-glide, or when it is variable.

- Notes

- ⟨a⟩ officially represents a front vowel, but there is little if any distinction between front and central open vowels (see Vowel § Acoustics), and ⟨a⟩ is frequently used for an open central vowel.[48] If disambiguation is required, the retraction diacritic or the centralized diacritic may be added to indicate an open central vowel, as in ⟨a̠⟩ or ⟨ä⟩.

Remove ads

Diacritics and prosodic notation

Summarize

Perspective

Diacritics are used for phonetic detail. They are added to IPA letters to indicate a modification or specification of that letter's normal pronunciation.[74]

By being made superscript, any IPA letter may function as a diacritic, conferring elements of its articulation to the base letter.[75] Those superscript letters listed below are specifically provided for by the IPA Handbook; other uses can be illustrated with ⟨tˢ⟩ ([t] with fricative release), ⟨ᵗs⟩ ([s] with affricate onset), ⟨ⁿd⟩ (prenasalized [d]), ⟨bʱ⟩ ([b] with breathy voice), ⟨mˀ⟩ (glottalized [m]), ⟨sᶴ⟩ ([s] with a flavor of [ʃ], i.e. a voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant), ⟨oᶷ⟩ ([o] with diphthongization), ⟨ɯᵝ⟩ (compressed [ɯ]). Superscript diacritics placed after a letter are ambiguous between simultaneous modification of the sound and phonetic detail at the end of the sound. For example, labialized ⟨kʷ⟩ may mean either simultaneous [k] and [w] or else [k] with a labialized release. Superscript diacritics placed before a letter, on the other hand, normally indicate a modification of the onset of the sound (⟨mˀ⟩ glottalized [m], ⟨ˀm⟩ [m] with a glottal onset). (See § Superscript IPA.)

Notes:

- With aspirated voiced consonants, the aspiration is usually also voiced (voiced aspirated – but see voiced consonants with voiceless aspiration). Many linguists prefer one of the diacritics dedicated to breathy voice over simple aspiration, such as ⟨b̤⟩. Some linguists restrict that diacritic to sonorants, such as breathy-voice ⟨m̤⟩, and transcribe voiced-aspirated obstruents as e.g. ⟨bʱ⟩.

- These are relative to the cardinal value of the letter. They can also apply to unrounded vowels: [ɛ̜] is more spread (less rounded) than cardinal [ɛ], and [ɯ̹] is less spread than cardinal [ɯ].[76]

Since ⟨xʷ⟩ can mean that the [x] is labialized (rounded) throughout its articulation, and ⟨x̜⟩ makes no sense ([x] is already completely unrounded), ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ can only mean a less-labialized/rounded [xʷ]. However, readers might mistake ⟨x̜ʷ⟩ for "[x̜]" with a labialized off-glide, or might wonder if the two diacritics cancel each other out. Placing the 'less rounded' diacritic under the labialization diacritic, ⟨xʷ̜⟩, makes it clear that it is the labialization that is 'less rounded' than its cardinal IPA value.

A diacritic may be moved to avoid conflicts of space. One that is normally placed below a letter may be moved above it to avoid a descender or another diacritic, as with the voiceless ring on ⟨ŋ̊⟩, and vice versa with the tie bar on ⟨t͜s⟩, though the tie bar is basically in free variation.[74] Exceptions are the tilde, trema and caron/wedge – and, in extIPA, the bridge – which are defined differently when placed above and below a letter. The raising and lowering diacritics have a third option of being set as spacing forms ⟨˔⟩, ⟨˕⟩ that avoid both descenders and ascenders.

A couple additional superscript letters are found for secondary articulation. In the Handbook, for example, ⟨ʱ⟩ is used for voiced aspiration. ⟨ᶣ⟩ is commonly seen with languages such as Twi where consonants may be simultaneously palatalized and labialized, while ⟨ˀ⟩ may be used for glottalized sounds without specifying whether they are ejective or have creaky voice. ExtIPA provides ⟨ʶ⟩ for uvularization, and the Voice Quality Symbols provide a couple more. However, only limited set of IPA letters are used in this fashion; for all others, superscripting indicates more ambiguous shading of the sound.

The state of the glottis can be finely transcribed with diacritics. A series of alveolar plosives ranging from open-glottis to closed-glottis phonation is:

Additional diacritics are provided by the Extensions to the IPA for speech pathology.

Suprasegmentals

These symbols describe the features of a language above the level of individual consonants and vowels, that is, at the level of syllable, word or phrase. These include prosody, pitch, length, stress, intensity, tone and gemination of the sounds of a language, as well as the rhythm and intonation of speech.[77] Various ligatures of pitch/tone letters and diacritics are provided for by the Kiel Convention and used in the IPA Handbook despite not being found in the summary of the IPA alphabet found on the one-page chart.

Under capital letters below we will see how a carrier letter may be used to indicate suprasegmental features such as labialization or nasalization. Some authors omit the carrier letter, for e.g. suffixed [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ or prefixed [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟],[note 22] or place a spacing variant of a diacritic such as ⟨˔⟩ or ⟨˜⟩ at the beginning or end of a word to indicate that it applies to the entire word.[note 23]

Notes:

The old staveless tone letters, which are effectively obsolete, include high ⟨ˉe⟩, mid ⟨−e⟩ [not supported by Unicode], low ⟨ˍe⟩, rising ⟨ˊe⟩, falling ⟨ˋe⟩, low rising ⟨ˏe⟩ and low falling ⟨ˎe⟩.

Stress

Officially, the stress marks ⟨ˈ ˌ⟩ appear before the stressed syllable, and thus mark the syllable boundary as well as stress (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a period).[80] Occasionally the stress mark is placed immediately before the nucleus of the syllable, after any consonantal onset.[81] In such transcriptions, the stress mark does not mark a syllable boundary. The primary stress mark may be doubled ⟨ˈˈ⟩ for extra stress (such as prosodic stress). The secondary stress mark is sometimes seen doubled ⟨ˌˌ⟩ for extra-weak stress, but this convention has not been adopted by the IPA.[80] Some dictionaries place both stress marks before a syllable, ⟨¦⟩, to indicate that pronunciations with either primary or secondary stress are heard, though this is not IPA usage.[note 29]

Boundary markers

There are three boundary markers: ⟨.⟩ for a syllable break, ⟨|⟩ for a minor prosodic break and ⟨‖⟩ for a major prosodic break. The tags 'minor' and 'major' are intentionally ambiguous. Depending on need, 'minor' may vary from a foot break to a break in list-intonation to a continuing–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a comma), and while 'major' is often any intonation break, it may be restricted to a final–prosodic unit boundary (equivalent to a period). The 'major' symbol may also be doubled, ⟨‖‖⟩, for a stronger break.[note 30]

Although not part of the IPA, the following additional boundary markers are often used in conjunction with the IPA: ⟨μ⟩ for a mora or mora boundary, ⟨σ⟩ for a syllable or syllable boundary, ⟨+⟩ for a morpheme boundary, ⟨#⟩ for a word boundary (may be doubled, ⟨##⟩, for e.g. a breath-group boundary),[83] ⟨$⟩ for a phrase or intermediate boundary and ⟨%⟩ for a prosodic boundary. For example, C# is a word-final consonant, %V a post-pausa vowel, and σC a syllable-initial consonant.

Pitch and tone

⟨ꜛ ꜜ⟩ are defined in the Handbook as "upstep" and "downstep", concepts from tonal languages. However, the upstep symbol can also be used for pitch reset, and the IPA Handbook uses it for prosody in the illustration for Portuguese, a non-tonal language.

Phonetic pitch and phonemic tone may be indicated by either diacritics placed over the nucleus of the syllable – e.g., high-pitch ⟨é⟩ – or by Chao tone letters placed either before or after the word or syllable. There are three graphic variants of the tone letters: with or without a stave, and facing left or facing right from the stave. The stave was introduced with the 1989 Kiel Convention, as was the option of placing a staved letter after the word or syllable, while retaining the older conventions. There are therefore six ways to transcribe pitch/tone in the IPA: i.e., ⟨é⟩, ⟨˦e⟩, ⟨e˦⟩, ⟨꜓e⟩, ⟨e꜓⟩ and ⟨ˉe⟩ for a high pitch/tone.[80][84][85] Of the tone letters, only left-facing staved letters and a few representative combinations are shown in the summary on the Chart, and in practice it is currently more common for tone letters to occur after the syllable/word than before, as in the Chao tradition. Placement before the word is a carry-over from the pre-Kiel IPA convention, as is still the case for the stress and upstep/downstep marks. The IPA endorses the Chao tradition of using the left-facing tone letters, ⟨˥ ˦ ˧ ˨ ˩⟩, for underlying tone, and the right-facing letters, ⟨꜒ ꜓ ꜔ ꜕ ꜖⟩, for surface tone, as occurs in tone sandhi, and for the intonation of non-tonal languages. In the Portuguese illustration in the 1999 Handbook, for example, tone letters are placed before a word or syllable to indicate prosodic pitch (equivalent to [↗︎] global rise and [↘︎] global fall, but allowing more precision), and in the Cantonese illustration they are placed after a word/syllable to indicate lexical tone. Theoretically therefore prosodic pitch and lexical tone could be simultaneously transcribed in a single text, though this is not a formalized distinction.

Rising and falling pitch, as in contour tones, are indicated by combining the pitch diacritics and letters in the table, such as grave plus acute for rising [ě] and acute plus grave for falling [ê]. Only six combinations of two diacritics are supported, and only across three levels (high, mid, low), despite the diacritics supporting five levels of pitch in isolation. The four other explicitly approved rising and falling diacritic combinations are high/mid rising [e᷄], low rising [e᷅], high falling [e᷇], and low/mid falling [e᷆].[note 31]

The Chao tone letters, on the other hand, may be combined in any pattern, and are therefore used for more complex contours and finer distinctions than the diacritics allow, such as mid-rising [e˨˦], extra-high falling [e˥˦], etc. There are 20 such possibilities. However, in Chao's original proposal, which was adopted by the IPA in 1989, he stipulated that the half-high and half-low letters ⟨˦ ˨⟩ may be combined with each other, but not with the other three tone letters, so as not to create spuriously precise distinctions. With this restriction, there are 8 possibilities.[86]

The old staveless tone letters tend to be more restricted than the staved letters, though not as restricted as the diacritics. Technically they support as many distinctions as the staved letters,[note 32] but in the decades prior to the Kiel Convention only three pitch levels were provided for level tones, and only two for contour tones. Unicode supports default or high-pitch ⟨ˉ ˊ ˋ ˆ ˇ ˜ ˙⟩ and low-pitch ⟨ˍ ˏ ˎ ꞈ ˬ ˷⟩. Only a single mid-pitch tone is supported: ⟨˴⟩. The IPA had also used dots for neutral tones, but the corresponding dotted Chao tone letters were not adopted at the Kiel Convention.

Although tone diacritics and tone letters are presented as equivalent on the chart, "this was done only to simplify the layout of the chart. The two sets of symbols are not comparable in this way."[87] Using diacritics, a high tone is ⟨é⟩ and a low tone is ⟨è⟩; in tone letters, these are ⟨e˥⟩ and ⟨e˩⟩. One can double the diacritics for extra-high ⟨e̋⟩ and extra-low ⟨ȅ⟩; there is no parallel to this using tone letters. Instead, tone letters have mid-high ⟨e˦⟩ and mid-low ⟨e˨⟩; again, there is no equivalent among the diacritics. Thus in a three-register tone system, ⟨é ē è⟩ are equivalent to ⟨e˥ e˧ e˩⟩, while in a four-register system, ⟨e̋ é è ȅ⟩ may be equivalent to ⟨e˥ e˦ e˨ e˩⟩.[80]

The correspondence breaks down even further once they start combining. For more complex tones, one may combine three or four tone diacritics in any permutation,[80] though in practice only generic peaking (rising-falling) e᷈ and dipping (falling-rising) e᷉ combinations are used. Chao tone letters are required for finer detail (e˧˥˧, e˩˨˩, e˦˩˧, e˨˩˦, etc.). Although only 10 peaking and dipping tones were proposed in Chao's original, limited set of tone letters, phoneticians often make finer distinctions, and indeed an example is found on the IPA Chart.[note 33] The system allows the transcription of 112 peaking and dipping pitch contours, including tones that are level for part of their length.

More complex contours are possible. Chao gave an example of [꜔꜒꜖꜔] (mid-high-low-mid) from English prosody.[86]

Chao tone letters generally appear after each syllable, for a language with syllable tone (e.g. ⟨a˧vɔ˥˩⟩) or after the phonological word, for a language with word tone (e.g. ⟨avɔ˧˥˩⟩). The IPA gives the option of placing the tone letters before the word or syllable (⟨˧a˥˩vɔ⟩, ⟨˧˥˩avɔ⟩), and illustrates this for prosody, but it is rare for lexical tone. Reversed tone letters may be used to clarify that they apply to the following rather than to the preceding syllable (⟨꜔a꜒꜖vɔ⟩, ⟨꜔꜒꜖avɔ⟩). The staveless letters are not directly supported by Unicode, but some fonts allow the stave in Chao tone letters to be suppressed.

Comparative degree

IPA diacritics may be doubled to indicate an extra degree (greater intensity) of the feature indicated.[88] This is a productive process, but apart from extra-high and extra-low tones being marked by doubled high- and low-tone diacritics, ⟨ə̋, ə̏⟩, the major prosodic break ⟨‖⟩ being marked as a doubled minor break ⟨|⟩, and a couple other instances, such usage is not enumerated by the IPA.

For example, the stress mark may be doubled (or even tripled, as may be the prosodic-break bar, ⟨⦀⟩) to indicate an extra degree of stress, such as prosodic stress in English.[89] An example in French, with a single stress mark for normal prosodic stress at the end of each prosodic unit (marked as a minor prosodic break), and a double or even triple stress mark for contrastive/emphatic stress: [ˈˈɑ̃ːˈtre | məˈsjø ‖ ˈˈvwala maˈdam ‖] Entrez monsieur, voilà madame.[90] Similarly, a doubled secondary stress mark ⟨ˌˌ⟩ is commonly used for tertiary (extra-light) stress, though a proposal to officially adopt this was rejected.[91] In a similar vein, the effectively obsolete staveless tone letters were once doubled for an emphatic rising intonation ⟨˶⟩ and an emphatic falling intonation ⟨˵⟩.[92]

Length is commonly extended by repeating the length mark, which may be phonetic, as in [ĕ e eˑ eː eːˑ eːː] etc., as in English shhh! [ʃːːː], or phonemic, as in the "overlong" segments of Estonian:

- vere /vere/ 'blood [gen.sg.]', veere /veːre/ 'edge [gen.sg.]', veere /veːːre/ 'roll [imp. 2nd sg.]'

- lina /linɑ/ 'sheet', linna /linːɑ/ 'town [gen. sg.]', linna /linːːɑ/ 'town [ill. sg.]'

(Normally additional phonemic degrees of length are handled by the extra-short or half-long diacritic, i.e. ⟨e eˑ eː⟩ or ⟨ĕ e eː⟩, but the first two words in each of the Estonian examples are analyzed as typically short and long, /e eː/ and /n nː/, requiring a different remedy for the additional words.)

Delimiters are similar: double slashes indicate extra phonemic (morpho-phonemic), double square brackets especially precise transcription, and double parentheses especially unintelligible.

Occasionally other diacritics are doubled:

- Rhoticity in Badaga /be/ "mouth", /be˞/ "bangle", and /be˞˞/ "crop".[93]

- Mild and strong aspiration, [kʰ], [kʰʰ].[note 36]

- Nasalization, as in Palantla Chinantec lightly nasalized /ẽ/ vs heavily nasalized /ẽ̃/,[94] though some care can be needed to distinguish this from the extIPA diacritic for velopharyngeal frication in disordered speech, /e͌/, which has also been analyzed as extreme nasalization.

- Weak vs strong ejectives, [kʼ], [kˮ].[95]

- Especially lowered, e.g. [t̞̞] (or [t̞˕], if the former symbol does not display properly) for /t/ as a weak fricative in some pronunciations of register.[96]

- Especially retracted, e.g. [ø̠̠] or [s̠̠],[note 37][88][97] though some care might be needed to distinguish this from indications of alveolar or alveolarized articulation in extIPA, e.g. [s͇].

- Especially guttural, e.g. [ɫ] (velarized l), [ꬸ] (pharyngealized l).[98]

- The transcription of strident and harsh voice as extra-creaky /a᷽/ may be motivated by the similarities of these phonations.

The extIPA provides combining parentheses for weak intensity, which when combined with a doubled diacritic indicate an intermediate degree. For instance, increasing degrees of nasalization of the vowel [e] might be written ⟨e ẽ᪻ ẽ ẽ̃᪻ ẽ̃⟩.

Remove ads

Ambiguous letters

Summarize

Perspective

As noted above, IPA letters are often used quite loosely in broad transcription if no ambiguity would arise in a particular language. Because of that, IPA letters have not generally been created for sounds that are not distinguished in individual languages. A distinction between voiced fricatives and approximants is only partially implemented by the IPA, for example. Even with the relatively recent addition of the palatal fricative ⟨ʝ⟩ and the velar approximant ⟨ɰ⟩ to the alphabet, other letters, though defined as fricatives, are often ambiguous between fricative and approximant. For forward places, ⟨β⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ can generally be assumed to be fricatives unless they carry a lowering diacritic. Rearward, however, ⟨ʁ⟩ and ⟨ʕ⟩ are perhaps more commonly intended to be approximants even without a lowering diacritic. ⟨h⟩ and ⟨ɦ⟩ are similarly either fricatives or approximants, depending on the language, or even glottal "transitions", without that often being specified in the transcription.

Another common ambiguity is among the letters for palatal consonants. ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ɟ⟩ are not uncommonly used as a typographic convenience for affricates, typically [t͜ʃ] and [d͜ʒ],[99] while ⟨ɲ⟩ and ⟨ʎ⟩ are commonly used for palatalized alveolar [n̠ʲ] and [l̠ʲ]. To some extent this may be an effect of analysis, but it is common to match up single IPA letters to the phonemes of a language, without overly worrying about phonetic precision.

It has been argued that the lower-pharyngeal (epiglottal) fricatives ⟨ʜ⟩ and ⟨ʢ⟩ are better characterized as trills, rather than as fricatives that have incidental trilling.[100] This has the advantage of merging the upper-pharyngeal fricatives [ħ, ʕ] together with the epiglottal plosive [ʡ] and trills [ʜ ʢ] into a single pharyngeal column in the consonant chart. However, in Shilha Berber the epiglottal fricatives are not trilled.[101][102] Although they might be transcribed ⟨ħ̠ ʢ̠⟩ to indicate this, the far more common transcription is ⟨ʜ ʢ⟩, which is therefore ambiguous between languages.

Among vowels, ⟨a⟩ is officially a front vowel, but is more commonly treated as a central vowel. The difference, to the extent it is even possible, is not phonemic in any language.

For all phonetic notation, it is good practice for an author to specify exactly what they mean by the symbols that they use.

Remove ads

Superscript letters

Summarize

Perspective

Superscript IPA letters are used to indicate secondary aspects of articulation. These may be aspects of simultaneous articulation that are considered to be in some sense less dominant than the basic sound, or may be transitional articulations that are interpreted as secondary elements.[103] Examples include secondary articulation; onsets, releases, aspiration and other transitions; shades of sound; light epenthetic sounds and incompletely articulated sounds. Morphophonemically, superscripts may be used for assimilation, e.g. ⟨aʷ⟩ for the effect of labialization on a vowel /a/, which may be realized as phonemic /o/.[104] The IPA and ICPLA endorse Unicode encoding of superscript variants of all contemporary segmental letters in the IPA proper and of all additional fricatives in extIPA, including the "implicit" IPA retroflex letters ⟨ꞎ 𝼅 𝼈 ᶑ 𝼊 ⟩.[46][75][105]

Superscripts are often used as a substitute for the tie bar, for example ⟨tᶴ⟩ for [t͜ʃ] and ⟨kᵖ⟩ or ⟨ᵏp⟩ for [k͜p]. However, in precise notation there is a difference between a fricative release in [tᶴ] and the affricate [t͜ʃ], between a velar onset in [ᵏp] and doubly articulated [k͜p].[106]

Superscript letters can be meaningfully modified by combining diacritics, just as baseline letters can. For example, a superscript dental nasal in ⟨ⁿ̪d̪⟩, a superscript voiceless velar nasal in ⟨ᵑ̊ǂ⟩, and labial-velar prenasalization in ⟨ᵑ͡ᵐɡ͡b⟩. Although the diacritic may seem a bit oversized compared to the superscript letter it modifies, e.g. ⟨ᵓ̃⟩, this can be an aid to legibility, just as it is with the composite superscript c-cedilla ⟨ᶜ̧⟩ and rhotic vowels ⟨ᵊ˞ ᶟ˞⟩. Superscript length marks can be used to indicate the length of aspiration of a consonant, e.g. [pʰ tʰ𐞂 kʰ𐞁]. Another option is to use extIPA parentheses and a doubled diacritic: ⟨p⁽ʰ⁾ tʰ kʰʰ⟩.[46]

Remove ads

Obsolete and nonstandard symbols

Summarize

Perspective

A number of IPA letters and diacritics have been retired or replaced over the years. This number includes duplicate symbols, symbols that were replaced due to user preference, and unitary symbols that were rendered with diacritics or digraphs to reduce the inventory of the IPA. The rejected symbols are now considered obsolete, though some are still seen in the literature.

The IPA once had several pairs of duplicate symbols from alternative proposals, but eventually settled on one or the other. An example is the vowel letter ⟨ɷ⟩, rejected in favor of ⟨ʊ⟩. Affricates were once transcribed with ligatures, such as ⟨ʧ ʤ ⟩ (and others, some of which are not found in Unicode). These have been officially retired but are still used. Letters for specific combinations of primary and secondary articulation have also been mostly retired, with the idea that such features should be indicated with tie bars or diacritics: ⟨ƍ⟩ for [zʷ] is one. In addition, the rare voiceless implosives, ⟨ƥ ƭ ƈ ƙ ʠ ⟩, were dropped soon after their introduction and are now usually written ⟨ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ʄ̊ ɠ̊ ʛ̥ ⟩. The original set of click letters, ⟨ʇ, ʗ, ʖ, ʞ⟩, was retired but is still sometimes seen, as the current pipe letters ⟨ǀ, ǃ, ǁ, ǂ⟩ can cause problems with legibility, especially when used with brackets ([ ] or / /), the letter ⟨l⟩ (small L), or the prosodic marks ⟨|, ‖⟩. (For this reason, some publications which use the current IPA pipe letters disallow IPA brackets.)[107]

Individual non-IPA letters may find their way into publications that otherwise use the standard IPA. This is especially common with:

- Affricates, such as the Americanist barred lambda ⟨ƛ⟩ for [t͜ɬ] or ⟨č⟩ for [t͜ʃ ].[note 38]

- The Karlgren letters for Chinese vowels, ⟨ɿ, ʅ , ʮ, ʯ ⟩.

- Digits or combinations of digits and letters for tonal phonemes that have conventional numbers in a local tradition, such as the four tones of Standard Chinese. This may be more convenient for comparison between related languages and dialects than a phonetic transcription would be, because tones vary more unpredictably than segmental phonemes do.

- Digits for tone levels, which are simpler to typeset, though the lack of standardization can cause confusion – e.g. ⟨1⟩ is high tone in some languages, but low tone in others; and ⟨3⟩ may be high, medium, or low tone, depending on the local convention.

- Iconic extensions of standard IPA letters that are implicit in the alphabet, such as retroflex ⟨ᶑ⟩ and ⟨ꞎ⟩. These are referred to in the Handbook and have been included in Unicode at IPA request.

- Even presidents of the IPA have used para-IPA notation, such as resurrecting the old diacritic ⟨◌̫⟩ for purely labialized sounds (not simultaneously velarized), the lateral fricative letter ⟨ꞎ ⟩, and either the old dot diacritic ⟨ṣ ẓ⟩ or the novel letters ⟨ ᶘ ᶚ⟩ for the not-quite-retroflex fricatives of Polish sz, ż and of Russian ш, ж.

In addition, it is common to see ad hoc typewriter substitutions, generally capital letters, for when IPA support is not available, e.g. S for ⟨ ʃ ⟩. (See also SAMPA and X-SAMPA substitute notation.)

Remove ads

Extensions

Summarize

Perspective

The Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet for Disordered Speech, commonly abbreviated "extIPA" and sometimes called "Extended IPA", are symbols whose original purpose was to accurately transcribe disordered speech. At the Kiel Convention in 1989, a group of linguists drew up the initial extensions,[note 39] which were based on the previous work of the PRDS (Phonetic Representation of Disordered Speech) Group in the early 1980s.[109] The extensions were first published in 1990, then modified, and published again in 1994 in the Journal of the International Phonetic Association, when they were officially adopted by the ICPLA.[110] While the original purpose was to transcribe disordered speech, linguists have used the extensions to designate a number of sounds within standard communication, such as hushing, gnashing teeth, and smacking lips,[2] as well as regular lexical sounds such as lateral fricatives that do not have standard IPA symbols.

In addition to the Extensions to the IPA for disordered speech, there are the conventions of the Voice Quality Symbols, which include a number of symbols for additional airstream mechanisms and secondary articulations in what they call "voice quality".

Remove ads

Associated notation

Summarize

Perspective

Capital letters and various characters on the number row of the keyboard are commonly used to extend the alphabet in various ways.

Associated symbols

There are various punctuation-like conventions for linguistic transcription that are commonly used together with IPA. Some of the more common are:

- ⟨*⟩

- (a) A reconstructed form.

- (b) An ungrammatical form (including an unphonemic form).

- ⟨**⟩

- (a) A reconstructed form, deeper (more ancient) than a single ⟨*⟩, used when reconstructing even further back from already-starred forms.

- (b) An ungrammatical form. A less common convention than ⟨*⟩ (b), this is sometimes used when reconstructed and ungrammatical forms occur in the same text.[111]

- ⟨×⟩, ⟨✗⟩

- An ungrammatical form. A less common convention than ⟨*⟩ (b), this is sometimes used when reconstructed and ungrammatical forms occur in the same text.[112]

- ⟨?⟩

- A doubtfully grammatical form.

- ⟨%⟩

- A generalized form, such as a typical shape of a wanderwort that has not actually been reconstructed.[113]

- ⟨#⟩

- A word boundary – e.g. ⟨#V⟩ for a word-initial vowel.

- ⟨$⟩

- A phonological word boundary; e.g. ⟨H$⟩ for a high tone that occurs in such a position.

- ⟨+⟩

- A morpheme boundary; e.g. ⫽ˈnɛl+t⫽ for English knelt.

- ⟨_⟩

- The location of a segment – e.g. ⟨V_V⟩ for an intervocalic position, or ⟨_#⟩ for word-final position.

- ⟨~⟩

- Alternation or contrast[citation needed] – e.g. [f] ~ [v] or [f ~ v] for variation between [f] and [v], noting that a /uː/ ~ /ʊ/ contrast is maintained or lost, or indicating the change of a root in e.g. ⫽ˈniːl ~ ˈnɛl+t⫽ for English kneel ~ knelt.

- ⟨∅⟩

- A null segment or morpheme. This may indicate the absence of an affix, e.g. ⟨kæt-∅⟩ for where an affix might appear but does not (cat instead of cats), or a deleted segment that leaves a feature behind, such as ⟨∅ʷ⟩ for an theoretical labialized segment that is only realized as labialization on adjacent segments.[104]

Capital letters

Full capital letters are not used as IPA symbols, except as typewriter substitutes (e.g. N for ⟨ŋ⟩, S for ⟨ ʃ ⟩, O for ⟨ɔ⟩ – see SAMPA). They are, however, often used in conjunction with the IPA in two cases:[citation needed]

- for (archi)phonemes and for natural classes of sounds (that is, as wildcards). The extIPA chart, for example, uses capital letters as wildcards in its illustrations.

- as carrying letters for the Voice Quality Symbols.

Wildcards are commonly used in phonology to summarize syllable or word shapes, or to show the evolution of classes of sounds. For example, the possible syllable shapes of Mandarin can be abstracted as ranging from /V/ (an atonic vowel) to /CGVNᵀ/ (a consonant-glide-vowel-nasal syllable with tone), and word-final devoicing may be schematized as C → C̥/_#. They are also used in historical linguistics for a sound that is posited but whose nature has not been determined beyond some generic category such as {nasal} or {uvular}. In speech pathology, capital letters represent indeterminate sounds, and may be superscripted to indicate they are weakly articulated: e.g. [ᴰ] is a weak indeterminate alveolar, [ᴷ] a weak indeterminate velar.[114]

There is a degree of variation between authors as to the capital letters used, but these are ubiquitous in English-language material:[115]

- ⟨C⟩ for {consonant}

- ⟨V⟩ for {vowel}

- ⟨N⟩ for {nasal}

Other common conventions are:[116]

- ⟨T⟩ for {tone/accent} (tonicity)

- ⟨P⟩ for {plosive}

- ⟨F⟩ for {fricative}

- ⟨S⟩ for {sibilant}[note 40]

- ⟨G⟩ for {glide/semivowel}

- ⟨L⟩ for {lateral} or {liquid}

- ⟨R⟩ for {rhotic} or {resonant/sonorant}[note 41]

- ⟨Ȼ⟩ for {obstruent}

- ⟨Ʞ⟩ for {click}

- ⟨A, E, Ɨ, O, U⟩ for {open, front, close, back, rounded vowel}[note 42] and ⟨B, D, Ɉ, K, Q, Φ, H⟩ for {labial, alveolar, post-alveolar/palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, glottal[note 43] consonant}, respectively

- ⟨X⟩ for {any sound}, as in ⟨CVX⟩ for a heavy syllable {CVC, CVV̯, CVː}

The letters can be modified with IPA diacritics, for example:[116]

- ⟨Cʼ⟩ for {ejective}

- ⟨Ƈ ⟩ for {implosive}

- ⟨N͡C⟩ or ⟨ᴺC⟩ for {prenasalized consonant}

- ⟨Ṽ⟩ for {nasal vowel}

- ⟨CʰV́⟩ for {aspirated CV syllable with high tone}

- ⟨S̬⟩ for {voiced sibilant}

- ⟨N̥⟩ for {voiceless nasal}

- ⟨P͡F⟩ or ⟨Pꟳ⟩ for {affricate}

- ⟨Cᴳ⟩ for a consonant with a glide as secondary articulation (e.g. ⟨Cʲ⟩ for {palatalized consonant} or ⟨Cʷ⟩ for {labialized consonant})

- ⟨D̪⟩ for {dental consonant}

⟨H⟩, ⟨M⟩, ⟨L⟩ are also commonly used for high, mid and low tone, with ⟨LH⟩ for rising tone and ⟨HL⟩ for falling tone, rather than transcribing them overly precisely with IPA tone letters or with ambiguous digits.[note 44] When distinguishing five levels of pitch, ⟨xH⟩ and ⟨xL⟩ may be used for 'extra high' and 'extra low'. Arbitrary sequences of letters such as ⟨A B C D⟩ may be used for tone phonemes, especially when comparing across related languages.

Typical examples of archiphonemic use of capital letters are:[citation needed]

- ⟨I⟩ for the Turkish harmonic vowel set {i y ɯ u}[note 45]

- ⟨D⟩ for the conflated flapped middle consonant of American English writer and rider

- ⟨N⟩ for the homorganic syllable-coda nasal of languages such as Spanish and Japanese (essentially equivalent to the wild-card usage of the letter)

- ⟨R⟩ in cases where a phonemic distinction between trill /r/ and flap /ɾ/ is conflated, as in Spanish enrejar /eNreˈxaR/ (the n is homorganic and the first r is a trill, but the second r is variable).[117]

Similar usage is found for phonemic analysis, where a language does not distinguish sounds that have separate letters in the IPA. For instance, Castillian Spanish has been analyzed as having phonemes /Θ/ and /S/, which surface as [θ] and [s] in voiceless environments and as [ð] and [z] in voiced environments (e.g. hazte /ˈaΘte/ → [ˈaθte], vs hazme /ˈaΘme/ → [ˈaðme], or las manos /laS ˈmanoS/ → [lazˈmanos]).[118]

⟨V⟩, ⟨F⟩ and ⟨C⟩ have completely different meanings as Voice Quality Symbols, where they stand for "voice" (VoQS jargon for secondary articulation),[note 46] "falsetto" and "creak". These three letters may take diacritics to indicate what kind of voice quality an utterance has, and may be used as carrier letters to extract a suprasegmental feature that occurs on all susceptible segments in a stretch of IPA. For instance, the transcription of Scottish Gaelic [kʷʰuˣʷt̪ʷs̟ʷ] 'cat' and [kʷʰʉˣʷt͜ʃʷ] 'cats' (Islay dialect) can be made more economical by extracting the suprasegmental labialization of the words: Vʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] and Vʷ[kʰʉˣt͜ʃ].[119] The conventional wildcards ⟨X⟩ or ⟨C⟩ might be used instead of VoQS ⟨V⟩ so that the reader does not misinterpret ⟨Vʷ⟩ as meaning that only vowels are labialized (i.e. Xʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] for all segments labialized, Cʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟] for all consonants labialized), or the carrier letter may be omitted altogether (e.g. ʷ[kʰuˣt̪s̟], [ʷkʰuˣt̪s̟] or [kʰuˣt̪s̟]ʷ). (See § Suprasegmentals for other transcription conventions.)

This summary is to some extent valid internationally, but linguistic material written in other languages may have different associations with capital letters used as wildcards. For example, in German ⟨K⟩ and ⟨V⟩ are used for Konsonant 'consonant' and Vokal 'vowel'; in Russian, ⟨С⟩ and ⟨Г⟩ are used for согласный (soglasnyj, 'consonant') and гласный (glasnyj, 'vowel'). In French, tone may be transcribed with ⟨H⟩ and ⟨B⟩ for haut 'high' and bas 'low';[120] Russian appears to be the opposite, with ⟨В⟩ for высокий (vysokij, 'high') and ⟨Н⟩ for низкий (nizkij, 'low').

Remove ads

Segments without letters

Summarize

Perspective

The blank cells on the summary IPA chart can be filled without much difficulty if the need arises.

The missing retroflex letters, namely ⟨ᶑ ꞎ 𝼅 𝼈 𝼊 ⟩, are "implicit" in the alphabet, and the IPA supported their adoption into Unicode.[46] Attested in the literature are the retroflex implosive ⟨ᶑ ⟩, the voiceless retroflex lateral fricative ⟨ꞎ ⟩, the retroflex lateral flap ⟨𝼈 ⟩ and the retroflex click ⟨𝼊 ⟩; the first is also mentioned in the IPA Handbook, and the lateral fricatives are provided for by the extIPA.

The epiglottal trill is arguably covered by the generally trilled epiglottal "fricatives" ⟨ʜ ʢ⟩. Ad hoc letters for near-close central vowels, ⟨ᵻ ᵿ⟩, are used in some descriptions of English, though those are specifically reduced vowels – forming a set with the IPA reduced vowels ⟨ə ɐ⟩ – and the simple points in vowel space are easily transcribed with diacritics: ⟨ɪ̈ ʊ̈⟩ or ⟨ɨ̞ ʉ̞⟩. Diacritics are able to fill in most of the remainder of the charts.[note 47] If a sound cannot be transcribed, an asterisk ⟨*⟩ may be used, either as a letter or as a diacritic (as in ⟨k*⟩ sometimes seen for the Korean "fortis" velar).

Consonants

Representations of consonant sounds outside of the core set are created by adding diacritics to letters with similar sound values. The Spanish bilabial and dental approximants are commonly written as lowered fricatives, [β̞] and [ð̞] respectively.[note 48] Similarly, voiced lateral fricatives can be written as raised lateral approximants, [ɭ˔ ʎ̝ ʟ̝], though the extIPA also provides ⟨𝼅⟩ for the first of these. A few languages such as Banda have a bilabial flap as the preferred allophone of what is elsewhere a labiodental flap. It has been suggested that this be written with the labiodental flap letter and the advanced diacritic, [ⱱ̟].[122] Similarly, a labiodental trill would be written [ʙ̪] (bilabial trill and the dental sign), and the labiodental plosives are now universally ⟨p̪ b̪⟩ rather than the ad hoc letters ⟨ȹ ȸ⟩ once found in Bantuist literature. Other taps can be written as extra-short plosives or laterals, e.g. [ ɟ̆ ɢ̆ ʟ̆], though in some cases the diacritic would need to be written below the letter. A retroflex trill can be written as a retracted [r̠], just as non-subapical retroflex fricatives sometimes are. The remaining pulmonic consonants – the uvular laterals ([ʟ̠ 𝼄̠ ʟ̠˔]) and the palatal trill – while not strictly impossible, are very difficult to pronounce and are unlikely to occur even as allophones in the world's languages.

Vowels

The vowels are similarly manageable by using diacritics for raising, lowering, fronting, backing, centering, and mid-centering.[note 49] For example, the unrounded equivalent of [ʊ] can be transcribed as mid-centered [ɯ̽], and the rounded equivalent of [æ] as raised [ɶ̝] or lowered [œ̞] (though for those who conceive of vowel space as a triangle, simple [ɶ] already is the rounded equivalent of [æ]). True mid vowels are lowered [e̞ ø̞ ɘ̞ ɵ̞ ɤ̞ o̞] or raised [ɛ̝ œ̝ ɜ̝ ɞ̝ ʌ̝ ɔ̝], while centered [ɪ̈ ʊ̈] and [ä] (or, less commonly, [ɑ̈]) are near-close and open central vowels, respectively.

The only known vowels that cannot be represented in this scheme are vowels with unexpected roundedness. For unambiguous transcription, such sounds would require dedicated diacritics. Possibilities include ⟨ʏʷ⟩ or ⟨ɪʷ⟩ for protrusion and ⟨uᵝ⟩ (or VoQS ⟨ɯᶹ⟩) for compression. However, these transcriptions suggest that the sounds are diphthongs, and so while they may be clear for a language like Swedish where they are diphthongs, they may be misleading for languages such as Japanese where they are monophthongs. The extIPA 'spread' diacritic ⟨◌͍⟩ is sometimes seen for compressed ⟨u͍⟩, ⟨o͍⟩, ⟨ɔ͍⟩, ⟨ɒ͍⟩, though again the intended meaning would need to be explained or they would be interpreted as being spread the way that cardinal ⟦i⟧ is. For protrusion (w-like labialization without velarization), Ladefoged & Maddieson use the old IPA omega diacritic for labialization, ⟨◌̫⟩, for protruded ⟨y᫇⟩, ⟨ʏ̫⟩, ⟨ø̫⟩, ⟨œ̫⟩. This is an adaptation of an old IPA convention of rounding an unrounded vowel letter like i with a subscript omega (⟨◌̫⟩) and unrounding a rounded letter like u with a subscript turned omega.[124] As of 2024[update], the turned omega diacritic is in the pipeline for Unicode, and is under consideration for compression in extIPA.[125] Kelly & Local use a combining w diacritic ⟨◌ᪿ⟩ for protrusion (e.g. ⟨yᷱ øᪿ⟩) and a combining ʍ diacritic ⟨◌ᫀ⟩ for compression (e.g. ⟨uᫀ oᫀ⟩).[126] Because their transcriptions are manuscript, these are effectively the same symbols as the old IPA diacritics, which indeed are historically cursive w and ʍ. However, the more angular ⟨◌ᫀ⟩ of typescript might misleadingly suggest the vowel is protruded and voiceless (like [ʍ]) rather than compressed and voiced.

Symbol names

Summarize

Perspective

In both print and speech, an IPA symbol is often distinguished from the sound it transcribes because IPA letters very often do not have their cardinal IPA values in practice. This is commonly the case in phonemic and broad phonetic transcription, making articulatory descriptions of IPA letters, such as "mid front rounded vowel" or "voiced velar stop", inappropriate as names for those letters. While the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association states that no official names exist for its symbols, it admits the presence of one or two common names for each.[127] The symbols also have nonce names in the Unicode standard. In many cases, the names in Unicode and the IPA Handbook differ. For example, the Handbook calls ⟨ɛ⟩ "epsilon", while Unicode calls it "small letter open e".

The traditional names of the Latin and Greek letters are usually used for unmodified letters.[note 50] Letters which are not directly derived from these alphabets, such as ⟨ʕ⟩, may have a variety of names, sometimes based on the appearance of the symbol or on the sound that it represents. In Unicode, some of the letters of Greek origin have Latin forms for use in IPA; the others use the characters from the Greek block.

For diacritics, there are two methods of naming. For traditional diacritics, the IPA notes the name in a well known language; for example, ⟨é⟩ is "e-acute", based on the name of the diacritic in English and French. Non-traditional diacritics are often named after objects they resemble, so ⟨d̪⟩ is called "d-bridge".

Geoffrey Pullum and William Ladusaw [d] list a variety of names in use for both current and retired IPA symbols in their Phonetic Symbol Guide. Many of them found their way into Unicode.[9]

Computer support

Summarize

Perspective

Unicode

Unicode supports nearly all of the IPA. Apart from basic Latin and Greek and general punctuation, the primary blocks are IPA Extensions, Spacing Modifier Letters and Combining Diacritical Marks, with lesser support from Phonetic Extensions, Phonetic Extensions Supplement, Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement, and scattered characters elsewhere. The extended IPA is supported primarily by those blocks and Latin Extended-G.

IPA numbers

After the Kiel Convention in 1989, most IPA symbols were assigned an identifying number to prevent confusion between similar characters during the printing of manuscripts. The codes were never much used and have been superseded by Unicode.

Typefaces

Many typefaces have support for IPA characters, but good diacritic rendering remains rare.[129] Web browsers generally do not need any configuration to display IPA characters, provided that a typeface capable of doing so is available to the operating system.

Free fonts

Typefaces that provide full IPA and nearly full extIPA support, including properly rendering the diacritics, include Gentium, Charis SIL, Doulos SIL, and Andika developed by SIL International. Indeed, the IPA chose Doulos to publish their chart in Unicode format. In addition to the level of support found in commercial and system fonts, these fonts support the full range of old-style (pre-Kiel) staveless tone letters, through a character variant option that suppresses the stave of the Chao tone letters. They also have an option to maintain the [a] ~ [ɑ] vowel distinction in italics. The only notable gaps are with the extIPA: the combining parentheses, which enclose diacritics, are not supported, nor is the enclosing circle that marks unidentified sounds, and which Unicode considers to be a copy-edit mark and thus not eligible for Unicode support.

The basic Latin Noto fonts commissioned by Google also have significant IPA support, including diacritic placement, only failing with the more obscure IPA and extIPA characters and superscripts of the Latin Extended-F and Latin Extended-G blocks. The extIPA parentheses are included, but they do not enclose diacritics as they are supposed to.

DejaVu is the second free Unicode font chosen by the IPA to publish their chart. It was last updated in 2016 and so does not support the Latin F or G blocks. Stacked diacritics tend to overstrike each other.

As of 2018[update], the IPA was developing their own font, unitipa, based on TIPA.[130][needs update]

Proprietary system fonts

Calibri, the former default font of Microsoft Office, has nearly complete IPA support with good diacritic rendering, though it is not as complete as some free fonts (see image at right). Other widespread Microsoft fonts, such as Arial and Times New Roman, have poor support.

The Apple system fonts Geneva, Lucida Grande and Hiragino (certain weights) have only basic IPA support.

Notable commercial fonts

Brill has complete IPA and extIPA coverage of characters added to Unicode by 2020, with good diacritic and tone-letter support. It is a commercial font but is freely available for non-commercial use.[131]

ASCII and keyboard transliterations

Several systems have been developed that map the IPA symbols to ASCII characters. Notable systems include SAMPA and X-SAMPA. The usage of mapping systems in on-line text has to some extent been adopted in the context input methods, allowing convenient keying of IPA characters that would be otherwise unavailable on standard keyboard layouts.

IETF language tags

IETF language tags have registered fonipa as a variant subtag identifying text as written in IPA.[132] Thus, an IPA transcription of English could be tagged as en-fonipa. For the use of IPA without attribution to a concrete language, und-fonipa is available.

Computer input using on-screen keyboard

Online IPA keyboard utilities are available, though none of them cover the complete range of IPA symbols and diacritics. Examples are the IPA 2018 i-charts hosted by the IPA,[133] IPA character picker by Richard Ishida at GitHub,[134] Type IPA phonetic symbols at TypeIt.org,[135] and an IPA Chart keyboard by Weston Ruter also at GitHub.[136] In April 2019, Google's Gboard for Android added an IPA keyboard to its platform.[137][138] For iOS there are multiple free keyboard layouts available, such as the IPA Phonetic Keyboard.[139]

See also

- Afroasiatic phonetic notation – Phonetic notation

- Americanist phonetic notation – Phonetic alphabet developed in the 1880s

- Articulatory phonetics – Branch of linguistics studying how humans make sounds

- Case variants of IPA letters – International Phonetic Alphabet variants

- Cursive forms of the International Phonetic Alphabet – Deprecated cursive forms of IPA symbols

- Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet – Disordered speech additions to the phonetic alphabet

- Index of phonetics articles

- International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration – Transliteration scheme for Indic scripts

- Sound correspondences between English accents

- List of international common standards

- Luciano Canepari – Italian linguist (born 1947)

- Phonetic symbols in Unicode

- RFE Phonetic Alphabet

- SAMPA – Computer-readable phonetic script

- Semyon Novgorodov – Yakut politician and linguist – inventor of IPA-based Yakut scripts

- TIPA – TeX macro package provides IPA support for LaTeX

- UAI phonetic alphabet – Phonetic transcription

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet – Phonetic alphabet for Uralic languages

- Voice Quality Symbols – Set of phonetic symbols used for voice quality, such as to transcribe disordered speech

- X-SAMPA – Remapping of the IPA into ASCII

Notes

- The inverted bridge minus under the ⟨t̺ʰ⟩ specifies it as apical (pronounced with the tip of the tongue), and the superscript h shows that it is aspirated (breathy); the rectangle under ⟨t̻⟩ specifies that it is laminal (pronounced with the blade of the tongue). These details cause the English /t/ to sound different from the French /t/.

- "From its earliest days [...] the International Phonetic Association has aimed to provide 'a separate sign for each distinctive sound; that is, for each sound which, being used instead of another, in the same language, can change the meaning of a word' [...] what became widely known in the twentieth century as the phoneme."[12]

- exceptions are affricates and diphthongs, which may be written as either simple sequences, such as ⟨ts⟩ and ⟨au⟩, or with tie bars or diacritics such as ⟨t͜s⟩ and ⟨au̯⟩ to clarify that they are single sounds.

- For instance, flaps and taps are two different kinds of articulation, but since no language has (yet) been found to make a distinction between, say, an alveolar flap and an alveolar tap, the IPA does not provide such sounds with dedicated letters. Instead, it provides a single letter – in this case, [ɾ] – for both. Strictly speaking, this makes the IPA a partially phonemic alphabet, not a purely phonetic one.

- This exception to the rules was made primarily to explain why the IPA does not make a dental–alveolar distinction, despite one being phonemic in hundreds of languages, including most of the continent of Australia. Americanist Phonetic Notation makes (or at least made) a distinction between apical ⟨t d s z n l⟩ and laminal ⟨τ δ ς ζ ν λ⟩, which is easily applicable to alveolar vs dental (when a language distinguishes apical alveolar from laminal dental, as in Australia), but despite several proposals to the Council, the IPA never voted to accept such a distinction. There are however other common phonemic distinctions that are made with diacritics, such as ⟨ʰ⟩ for aspirated consonants – a phonemic distinction made by thousands of languages – and ⟨ʲ⟩ for palatalized consonants, which were once transcribed by distinct letters until those letters were retired in favor of the diacritic.

- There are three basic tone diacritics and five basic tone letters, both sets of which may be compounded.

- "The non-roman letters of the International Phonetic Alphabet have been designed as far as possible to harmonize well with the roman letters. The Association does not recognize makeshift letters; It recognizes only letters which have been carefully cut so as to be in harmony with the other letters."[14]

- Originally, [ʊ] was written as a small capital U. However, this was not easy to read, and so it was replaced with a turned small capital omega. In modern typefaces, it often has its own design, called a "horseshoe".

- For example, Merriam-Webster dictionaries use backslashes \ ... \ to demarcate their in-house diaphonemic transcription system. This contrasts with the Oxford English Dictionary, which transcribes a specific target accent.

- For example, single and double pipe symbols are used for minor and major prosodic breaks. Although the Handbook specifies the prosodic symbols as being "thick" vertical lines, which would in theory be distinct from simple ASCII pipes used as delimiters (and similar to Dania transcription), this was an idea to keep them distinct from the otherwise similar pipes used as click letters, and is almost never found in practice.[27] The Handbook assigns the prosodic pipe the Unicode encodings U+007C, which is the simple ASCII symbol, and the double pipe U+2016.[28]