Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Parliamentary system

Form of government From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government based on the fusion of powers. In this system the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the parliament, to which they are held accountable. This head of government is usually, but not always, distinct from a ceremonial head of state. This is in contrast to a presidential system, which features a president who is not fully accountable to the legislature, and cannot be replaced by a simple majority vote.

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (December 2025) |

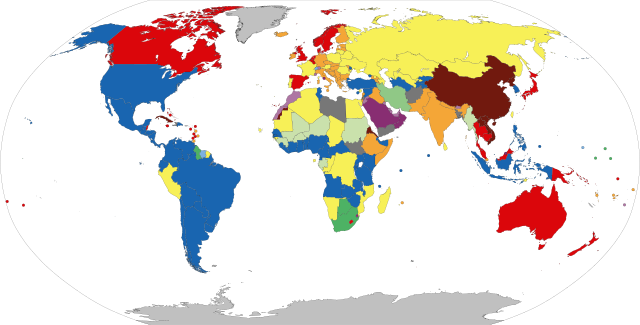

Parliamentary systems: Head of government is elected or nominated by and accountable to the legislature.

Presidential system: Head of government (president) is popularly elected and independent of the legislature.

Presidential republic

Hybrid systems:

Semi-presidential republic: Executive president is independent of the legislature; head of government is appointed by the president and is accountable to the legislature.

Assembly-independent republic: Head of government (president or directory) is elected by the legislature, but is not accountable to it.

Other systems:

Theocratic republic: Supreme Leader is both head of state and faith and holds significant executive and legislative power

Semi-constitutional monarchy: Monarch holds significant executive or legislative power but is still restricted by the constitution.

Military junta: Committee of military leaders controls the government; constitutional provisions are suspended.

Governments with no constitutional basis: No constitutionally defined basis to current regime, i.e., provisional governments or Islamic theocracies.

Dependent territories or places without governments

Note: this chart represents the de jure systems of government, not the de facto degree of democracy.

Countries with parliamentary systems may be constitutional monarchies, where a monarch is the head of state while the head of government is almost always a member of parliament, or parliamentary republics, where a mostly ceremonial president is the head of state while the head of government is from the legislature. In a few countries, the head of government is also head of state but is elected by the legislature. In bicameral parliaments, the head of government is generally, though not always, a member of the lower house.

Parliamentary democracy is the predominant form of government in the European Union, Oceania, and throughout the former British Empire, with other users scattered throughout Africa and Asia. A similar system, called a council–manager government, is used by many local governments in the United States.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The first parliaments date back to Europe in the Middle Ages. The earliest example of a parliament is disputed, especially depending how the term is defined.

For example, the Icelandic Althing consisting of prominent individuals among the free landowners of the various districts of the Icelandic Commonwealth first gathered around the year 930 (it conducted its business orally, with no written record allowing an exact date).

The first written record of a parliament, in particular in the sense of an assembly separate from the population called in presence of a king was in 1188, when Alfonso IX, King of Leon (Spain) convened the three states in the Cortes of León.[1][2] The Corts of Catalonia were the first parliament of Europe that officially obtained the power to pass legislation, apart from the custom.[3] An early example of parliamentary government also occurred in today's Netherlands and Belgium during the Dutch revolt (1581), when the sovereign, legislative and executive powers were taken over by the States General of the Netherlands from the monarch, King Philip II of Spain.[citation needed] Significant developments Kingdom of Great Britain, in particular in the period 1707 to 1800 and its contemporary, the Parliamentary System in Sweden between 1721 and 1772, and later in Europe and elsewhere in the 19th and 20th centuries, with the expansion of like institutions, and beyond

In England, Simon de Montfort is remembered as one of the figures relevant later for convening two famous parliaments.[4][5][6] The first, in 1258, stripped the king of unlimited authority and the second, in 1265, included ordinary citizens from the towns.[7] Later, in the 17th century, the Parliament of England pioneered some of the ideas and systems of liberal democracy culminating in the Glorious Revolution and passage of the Bill of Rights 1689.[8][9]

In the Kingdom of Great Britain, the monarch, in theory, chaired the cabinet and chose ministers. In practice, King George I's inability to speak English led to the responsibility for chairing cabinet to go to the leading minister, literally the prime or first minister, Robert Walpole. The gradual democratisation of Parliament with the broadening of the voting franchise increased Parliament's role in controlling government, and in deciding whom the king could ask to form a government. By the 19th century, the Great Reform Act 1832 led to parliamentary dominance, with its choice invariably deciding who was prime minister and the complexion of the government.[10][11]

Other countries gradually adopted what came to be called the Westminster system of government,[12] with an executive answerable to the lower house of a bicameral parliament, and exercising, in the name of the head of state, powers nominally vested in the head of state – hence the use of phrases such as Her Majesty's government (in constitutional monarchies) or His Excellency's government (in parliamentary republics).[13] Such a system became particularly prevalent in older British dominions, many of which had their constitutions enacted by the British parliament; such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the Irish Free State and the Union of South Africa.[14][15][16] Some of these parliaments were reformed from, or were initially developed as distinct from their original British model: the Australian Senate, for instance, has since its inception more closely reflected the US Senate than the British House of Lords; whereas since 1950 there is no upper house in New Zealand. Many of these countries such as Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados have severed institutional ties to Great Britain by becoming republics with their own ceremonial presidents, but retain the Westminster system of government. The idea of parliamentary accountability and responsible government spread with these systems.[17]

Democracy and parliamentarianism became increasingly prevalent in Europe in the years after World War I, partially imposed by the democratic victors,[how?] the United States, Great Britain and France, on the defeated countries and their successors, notably Germany's Weimar Republic and the First Austrian Republic. Nineteenth-century urbanisation, the Industrial Revolution and modernism had already made the parliamentarist demands of the Radicals and the emerging movement of social democrats increasingly impossible to ignore; these forces came to dominate many states that transitioned to parliamentarism, particularly in the French Third Republic where the Radical Party and its centre-left allies dominated the government for several decades. However, the rise of Fascism in the 1930s put an end to parliamentary democracy in Italy and Germany, among others.

After the Second World War, the defeated fascist Axis powers were occupied by the victorious Allies. In those countries occupied by the Allied democracies (the United States, United Kingdom, and France) parliamentary constitutions were implemented, resulting in the parliamentary constitutions of Italy and West Germany (now all of Germany) and the 1947 Constitution of Japan. The experiences of the war in the occupied nations where the legitimate democratic governments were allowed to return strengthened the public commitment to parliamentary principles; in Denmark, a new constitution was written in 1953, while a long and acrimonious debate in Norway resulted in no changes being made to that country's strongly entrenched democratic constitution.

Remove ads

Characteristics

Summarize

Perspective

A parliamentary system may be either bicameral, with two chambers of parliament (or houses) or unicameral, with just one parliamentary chamber. A bicameral parliament usually consists of a directly elected lower house with the power to determine the executive government, and an upper house which may be appointed or elected through a different mechanism from the lower house.

A 2019 peer-reviewed meta-analysis based on 1,037 regressions in 46 studies finds that presidential systems generally seem to favor revenue cuts, while parliamentary systems would rely more on fiscal expansion characterized by a higher level of spending before an election.[18]

Types

Scholars of democracy such as Arend Lijphart distinguish two types of parliamentary democracies: the Westminster and Consensus systems.[19]

Westminster system

- The Westminster system is usually found in the Commonwealth of Nations and countries which were influenced by the British political tradition.[20][21][22] These parliaments tend to have a more adversarial style of debate and the plenary session of parliament is more important than committees. Some parliaments in this model are elected using a plurality voting system (first past the post), such as the United Kingdom, Canada, India and Malaysia, while others use some form of proportional representation, such as Ireland and New Zealand. The Australian House of Representatives is elected using instant-runoff voting, while the Senate is elected using proportional representation through single transferable vote. Regardless of which system is used, the voting systems tend to allow the voter to vote for a named candidate rather than a closed list. Most Westminster systems employ strict monism, where ministers must be members of parliament simultaneously; while some Westminster systems, such as Bangladesh,[23] permit the appointment of extra-parliamentary ministers, and others (such as Jamaica) allow outsiders to be appointed to the ministry through an appointed upper house, although a majority of ministers (which, by necessity, includes the prime minister) must come from within (the lower house of) the parliament.

Consensus system

- The Western European parliamentary model (e.g., Spain, Germany) tends to have a more consensual debating system and usually has semi-circular debating chambers. Consensus systems have more of a tendency to use proportional representation with open party lists than the Westminster Model legislatures. The committees of these parliaments tend to be more important than the plenary chamber. Most Western European countries do not employ strict monism, and allow extra-parliamentary ministers as a matter of course. The Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden outright implement the principle of dualism as a form of separation of powers, where Members of Parliament have to resign their place in Parliament upon being appointed (or elected) minister.

Appointment of the head of government

Implementations of the parliamentary system can also differ as to how the prime minister and government are appointed and whether the government needs the explicit approval of the parliament, rather than just the absence of its disapproval. While most parliamentary systems such as India require the prime minister and other ministers to be a member of the legislature, in other countries like Canada and the United Kingdom this only exists as a convention, some other countries including Norway, Sweden and the Benelux countries require a sitting member of the legislature to resign such positions upon being appointed to the executive.

- The head of state appoints a prime minister who will likely have majority support in parliament. While in the majority of cases prime ministers in the Westminster system are the leaders of the largest party in parliament, technically the appointment of the prime minister is a prerogative exercised by the head of state (be it the monarch, the governor-general, or the president). This system is used in:

- The head of state appoints a prime minister who must gain a vote of confidence within a set time. This system is used in:

- The head of state appoints the leader of the political party holding a plurality of seats in parliament as prime minister. For example, in Greece, if no party has a majority, the leader of the party with a plurality of seats is given an exploratory mandate to receive the confidence of the parliament within three days. If said leader fails to obtain the confidence of parliament, then the leader of the second-largest party is given the exploratory mandate. If that fails, then the leader of the third-largest political party is given the exploratory mandate, and so on. This system is used in:

- The head of state nominates a candidate for prime minister who is then submitted to parliament for approval before appointment. Example: Spain, where the King sends a proposal to the Congress of Deputies for approval. Also, Germany where under the German Basic Law (constitution) the Bundestag votes on a candidate nominated by the federal president. In these cases, parliament can choose another candidate who then would be appointed by the head of state. This system is used in:

- Parliament nominates a candidate whom the head of state is constitutionally obliged to appoint as prime minister. Example: Japan, where the Emperor appoints the Prime Minister on the nomination of the National Diet. Also Ireland, where the President of Ireland appoints the Taoiseach on the nomination of Dáil Éireann. This system is used in:

- A public officeholder (other than the head of state or their representative) nominates a candidate, who, if approved by parliament, is appointed as prime minister. Example: Under the Swedish Instrument of Government (1974), the power to appoint someone to form a government has been moved from the monarch to the Speaker of Parliament and the parliament itself. The speaker nominates a candidate, who is then elected to prime minister (statsminister) by the parliament if an absolute majority of the members of parliament does not vote against the candidate (i.e. they can be elected even if more members of parliament vote No than Yes). This system is used in:

- Direct election by popular vote. Example: Israel, 1996–2001, where the prime minister was elected in a general election, with no regard to political affiliation, and whose procedure can also be described as of a semi-parliamentary system.[26][27] This system was used in:

Israel (1996–2001)

Israel (1996–2001)

Power of dissolution and call for election

Furthermore, there are variations as to what conditions exist (if any) for the government to have the right to dissolve the parliament:

- In some countries, especially those operating under a Westminster system, such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, Malaysia, Australia and New Zealand, the prime minister has the de facto power to call an election, at will. In Spain, the prime minister is the only person with the de jure power to call an election, granted by Article 115 of the Constitution.

- In Israel, parliament may vote to dissolve itself in order to call an election, or the prime minister may call a snap election with presidential consent if his government is deadlocked. A non-passage of the budget automatically calls a snap election.

- Other countries only permit an election to be called in the event of a vote of no confidence against the government, a supermajority vote in favour of an early election or a prolonged deadlock in parliament. These requirements can still be circumvented. For example, in Germany in 2005, Gerhard Schröder deliberately allowed his government to lose a confidence motion, in order to call an early election.

- In Sweden, the government may call a snap election at will, but the newly elected Riksdag is only elected to fill out the previous Riksdag's term. The last time this option was used was in 1958.

- In Greece, a general election is called if the Parliament fails to elect a new head of state when his or her term ends. In January 2015, this constitutional provision was exploited by Syriza to trigger a snap election, win it and oust rivals New Democracy from power.

- In Italy the government has no power to call a snap election. A snap election can only be called by the head of state, following a consultation with the presidents of both houses of parliament.

- Norway is unique among parliamentary systems in that the Storting always serves the whole of its four-year term.

- In Australia, under certain, unique conditions, the prime minister can request the Governor General to call for a double dissolution, whereby all rather than only half of the Senate, is dissolved – in effect electing all of the Parliament simultaneously.

The parliamentary system can be contrasted with a presidential system which operates under a stricter separation of powers, whereby the executive does not form part of—nor is appointed by—the parliamentary or legislative body. In such a system, parliaments or congresses do not select or dismiss heads of government, and governments cannot request an early dissolution as may be the case for parliaments (although the parliament may still be able to dissolve itself, as in the case of Cyprus). There also exists the semi-presidential system that draws on both presidential systems and parliamentary systems by combining a powerful president with an executive responsible to parliament: for example, the French Fifth Republic.

Parliamentarianism may also apply to regional and local governments. An example is Oslo which has an executive council (Byråd) as a part of the parliamentary system. The devolved nations of the United Kingdom are also parliamentary and which, as with the UK Parliament, may hold early elections – this has only occurred with regards to the Northern Ireland Assembly in 2017 and 2022.

Anti-defection law

A few parliamentary democratic nations such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have enacted laws that prohibit floor crossing or switching parties after the election. Under these laws, elected representatives will lose their seat in the parliament if they go against their party in votes.[28][29][30]

In the UK parliament, a member is free to cross over to a different party. In Canada and Australia, there are no restraints on legislators switching sides.[31] In New Zealand, waka-jumping legislation provides that MPs who switch parties or are expelled from their party may be expelled from Parliament at the request of their former party's leader.

Parliamentary sovereignty

A few parliamentary democracies such as the United Kingdom and New Zealand have weak or non-existent checks on the legislative power of their Parliaments,[32][33] where any newly approved Act shall take precedence over all prior Acts. All laws are equally unentrenched, wherein judicial review may not outright annul nor amend them, as frequently occurs in other parliamentary systems like Germany. Whilst the head of state for both nations (Monarch, and or Governor General) has the de jure power to withhold assent to any bill passed by their Parliament, this check has not been exercised in Britain since the 1708 Scottish Militia Bill.

Whilst both the UK and New Zealand have some Acts or parliamentary rules establishing supermajorities or additional legislative procedures for certain legislation, such as previously with the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (FTPA), these can be bypassed through the enactment of another that amends or ignores these supermajorities away, such as with the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 – bypassing the 2/3rd supermajority required for an early dissolution under the FTPA[34] -, which enabled the early dissolution for the 2019 general election.

Metrics

Parliamentarism metrics allow a quantitative comparison of the strength of parliamentary systems for individual countries. One parliamentarism metric is the Parliamentary Powers Index.[35]

Remove ads

Advantages

Summarize

Perspective

Adaptability

Parliamentary systems like that found in the United Kingdom are widely considered to be more flexible, allowing a rapid change in legislation and policy as long as there is a stable majority or coalition in parliament, allowing the government to have 'few legal limits on what it can do'[36] When combined with first-past-the-post voting, this system produces the classic "Westminster model" with the twin virtues of strong but responsive party government.[37] This electoral system providing a strong majority in the House of Commons, paired with the fused power system results in a particularly powerful government able to provide change and 'innovate'.[36]

Scrutiny and accountability

The United Kingdom's fused power system is often noted to be advantageous with regard to accountability. The centralised government allows for more transparency as to where decisions originate from, this contrasts with the American system with Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon saying "the president blames Congress, the Congress blames the president, and the public remains confused and disgusted with government in Washington".[38] Furthermore, ministers of the U.K. cabinet are subject to weekly Question Periods in which their actions/policies are scrutinised; no such regular check on the government exists in the U.S. system.

Distribution of power

A 2001 World Bank study found that parliamentary systems are associated with less corruption.[39]

Calling of elections

In his 1867 book The English Constitution, Walter Bagehot praised parliamentary governments for producing serious debates, for allowing for a change in power without an election, and for allowing elections at any time. Bagehot considered fixed-term elections such as the four-year election rule for presidents of the United States to be unnatural, as it can potentially allow a president who has disappointed the public with a dismal performance in the second year of his term to continue on until the end of his four-year term. Under a parliamentary system, a prime minister that has lost support in the middle of his term can be easily replaced by his own peers with a more popular alternative, as the Conservative Party in the UK did with successive prime ministers David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak.

Although Bagehot praised parliamentary governments for allowing an election to take place at any time, the lack of a definite election calendar can be abused. Under some systems, such as the British, a ruling party can schedule elections when it believes that it is likely to retain power, and so avoid elections at times of unpopularity. (From 2011, election timing in the UK was partially fixed under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, which was repealed by the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022.) Thus, by a shrewd timing of elections, in a parliamentary system, a party can extend its rule for longer than is feasible in a presidential system. This problem can be alleviated somewhat by setting fixed dates for parliamentary elections, as is the case in several of Australia's state parliaments. In other systems, such as the Dutch and the Belgian, the ruling party or coalition has some flexibility in determining the election date. Conversely, flexibility in the timing of parliamentary elections can avoid periods of legislative gridlock that can occur in a fixed period presidential system. In any case, voters ultimately have the power to choose whether to vote for the ruling party or someone else.

Remove ads

Disadvantages

Summarize

Perspective

Incomplete separation of power

According to Arturo Fontaine, parliamentary systems in Europe have yielded very powerful heads of government which is rather what is often criticized about presidential systems. Fontaine compares United Kingdom's Margaret Thatcher to the United States' Ronald Reagan noting the former head of government was much more powerful despite governing under a parliamentary system.[40] The rise to power of Viktor Orbán in Hungary has been claimed to show how parliamentary systems can be subverted.[40] The situation in Hungary was according to Fontaine allowed by the deficient separation of powers that characterises parliamentary and semi-presidential systems.[40] Once Orbán's party got two-thirds of the seats in Parliament in a single election, a supermajority large enough to amend the Hungarian constitution, there was no institution that was able to balance the concentration of power.[40] In a presidential system it would require at least two separate elections to create the same effect; the presidential election, and the legislative election, and that the president's party has the legislative supermajority required for constitutional amendments. Safeguards against this situation implementable in both systems include the establishment of an upper house or a requirement for external ratification of constitutional amendments such as a referendum. Fontaine also notes as a warning example of the flaws of parliamentary systems that if the United States had a parliamentary system, Donald Trump, as head of government, could have dissolved the United States Congress.[40]

Legislative flip-flopping

The ability for strong parliamentary governments to push legislation through with the ease of fused power systems such as in the United Kingdom, whilst positive in allowing rapid adaptation when necessary e.g. the nationalisation of services during the world wars, in the opinion of some commentators does have its drawbacks. For instance, the flip-flopping of legislation back and forth as the majority in parliament changed between the Conservatives and Labour over the period 1940–1980, contesting over the nationalisation and privatisation of the British Steel Industry resulted in major instability for the British steel sector.[36]

Political fragmentation

In R. Kent Weaver's book Are Parliamentary Systems Better?, he writes that an advantage of presidential systems is their ability to allow and accommodate more diverse viewpoints. He states that because "legislators are not compelled to vote against their constituents on matters of local concern, parties can serve as organizational and roll-call cuing vehicles without forcing out dissidents".[36]

Democratic unaccountability

All current parliamentary democracies see the indirect election or appointment of their head of government. As a result, the electorate has limited power to remove or install the person or party wielding the most power. Although strategic voting may enable the party of the prime minister to be removed or empowered, this can be at the expense of voters first preferences in the many parliamentary systems utilising first past the post, or having no effect in dislodging those parties who consistently form part of a coalition government, as with then Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte and his party the VVD's 4 terms in office, despite their peak support reaching only 26.6% in 2012.[41]

Remove ads

Countries

Summarize

Perspective

Africa

Americas

Asia

Europe

Oceania

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads