Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Pazeh language

Northwest Formosan language of Taiwan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Pazeh (also spelled Pazih, Pazéh) and Kaxabu are dialects of a language of the Pazeh and Kaxabu, neighboring Taiwanese indigenous peoples. The language is Formosan, of the Austronesian language family. The last remaining native speaker of the Pazeh dialect died in 2010, but 12 speakers of Kaxabu remain.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (July 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used - notably pzh for Pazeh. (November 2024) |

Remove ads

Classification

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

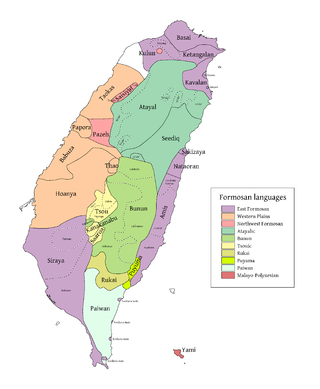

Pazeh and Kaxabu are classified as a Formosan language of the Austronesian language family.

Sound changes

The Pazih language merged the following Proto-Austronesian phonemes (Li 2001:7).

- *C, *S > s

- *D, *Z > d

- *k, *g > k

- *j, *s > z

- *S2, *H > h

- *N, *ñ > l

- *r, *R > x

Pazih also split some Proto-Austronesian phonemes:

- *S > s (merged with *C); *S2, *H > h

- *w > ø, w

- *e > e, u

Remove ads

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Due to prejudice faced by the Pazeh, as well as other indigenous groups of Taiwan, Hoklo Taiwanese came to displace Pazeh.[5][6]

The last remaining native speaker of the Pazeh dialect, Pan Jin-yu,[7] died in 2010 at the age of 96.[8] Before her death, she offered Pazeh classes to about 200 regular students in Puli and a small number of students in Miaoli and Taichung.[5] However, there are still efforts in revival of the language after her death.

Remove ads

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

Pazeh has 17 consonants, 4 vowels, and 4 diphthongs (-ay, -aw, -uy, -iw).[9]

- /t/ and /d/ do not actually share the same place of articulation; /d/ is alveolar or prealveolar and /t/ (as well as /n/) is interdental. Other coronal consonants tend to be prealveolar or post-dental.

- The distribution for the glottal stop is allophonic, appearing only between like vowels, before initial vowels, and after final vowels. It is also largely absent in normal speech

- /ɡ/ is spirantized intervocalically

- /z/ is actually an alveolar/prealveolar affricate [dz] and only occurs as a syllable onset.[11]

- /h/ varies between glottal and pharyngeal realizations ([ħ]) and is sometimes difficult to distinguish from /x/

Although Pazeh contrasts voiced and voiceless obstruents, this contrast is neutralized in final position for labial and velar stops, where only /p/ and /k/ occur respectively (/d/ is also devoiced but a contrast is maintained). /l/ and /n/ are also neutralized to the latter.[12] Voiceless stops are unreleased in final position.

Mid vowels ([ɛ] and [o]) are allophones of close vowels (/i/ and /u/ respectively).

- Both lower when adjacent to /h/.

- /u/ lowers before /ŋ/. [u] and [o] are in free variation before /ɾ/

- Reduplicated morphemes carry the phonetic vowel even when the reduplicated vowel is not in the phonological context for lowering.

- /mutapitapih/ → [mu.ta.pɛ.taˈpɛh] ('keep clapping').[14]

/a/ is somewhat advanced and raised when adjacent to /i/. Prevocally, high vowels are semivocalized. Most coronal consonants block this, although it still occurs after /s/. Semivowels also appear post-vocally.[15]

Phonotactics

The most common morpheme structure is CVCVC where C is any consonant and V is any vowel. Consonant clusters are rare and consist only of a nasal plus a homorganic obstruent or the glide element of a diphthong.[12]

Intervocalic voiceless stops are voiced before a morpheme boundary (but not following one) .[16] Stress falls on the ultimate syllable.[12]

Remove ads

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Like Bunun, Seediq, Squliq Atayal, Mantauran Rukai, and the Tsouic languages,[17] Pazeh does not distinguish between common nouns and personal names, whereas Saisiyat does (Li 2000). Although closely related to Saisiyat, the Pazeh language does not have the infix -um- that is present in Saisiyat.

Morphology

Pazeh makes ready use of affixes, infixes, suffixes, and circumfixes, as well as reduplication.[18] Pazeh also has "focus-marking" in its verbal morphology. In addition, verbs can be either stative or dynamic.

There are four types of focus in Pazeh (Li 2000).

- Agent-focus (AF): mu-, me-, mi-, m-, ma-, ∅-

- Patient-focus (PF) -en, -un

- Locative-focus (LF): -an

- Referential-focus (RF): sa-, saa-, si-

The following affixes are used in Pazeh verbs (Li 2000).

- -in- 'perfective'

- -a- 'progressive'

- -ay 'actor focus, irrealis', -aw 'patient focus, irrealis'

- -i 'non-agent-focused imperative'

The following are also used to mark aspect (Li 2000).

- Reduplication of the verb stem's first syllable – 'progressive'

- lia – "already"

Affixes

The Pazih affixes below are from Li (2001:10–19).

- Prefixes

- ha-: stative

- ka-: inchoative

- kaa-: nominal

- kai-: to stay at a certain location

- kali- -an: susceptible to, involuntarily

- m-: agent focus

- ma- (ka-): stative

- ma- (pa-): to have (noun); agent-focus

- maa[ka]- (paa[ka]-): – mutually, reciprocal

- maka- (paka-): to bear, bring forth

- mana- (pana-): to wash (body parts)

- mari- (pari-): to bear, to give birth (of animal)

- maru- (paru-): to lay eggs or give birth

- masa-: verbal prefix

- masi- (pasi-): to move, to wear

- mata-: (number of) times

- mati- (pati-): to carry, to wear, to catch

- matu- (patu-): to build, erect, set up

- maxa- (paxa-): to produce, to bring forth; to become

- maxi- (paxi-): to have, to bring forth; to look carefully

- me-, mi- (pi-), mi- (i-): agent-focus

- mia- (pia-): towards, to go

- mia- which one; ordinal (number)

- mu- (pu-): agent-focus (-um- in many other Formosan languages); to release

- pa-: verbalizer; causative, active verb

- paka-: causative, stative verb

- papa-: to ride

- pu-: to pave

- pu- -an: locative-focus, location

- sa- ~saa-, si-: instrumental-focus, something used to ..., tools

- si-: to have, to produce; to go (to a location)

- si- -an: to bring forth, to have a growth on one's body

- ta-: agentive, one specialized in ...; nominal prefix; verbal prefix

- tau-: agentive

- tau- -an: a gathering place

- taxa-: to feel like doing; to take a special posture

- taxi-: to lower one's body

- taxu-: to move around

- ti-: to get something undesirable or uncomfortable

- tu-: stative

- xi-: to turn over, to revert

- Infixes

- -a-: progressive, durative

- -in-: perfective

- Suffixes

- -an: locative-focus, location

- -an ~ -nan: locative pronoun or personal name

- -aw: patient-focus, future

- -ay: locative-focus, irrealis

- -en ~ -un: patient-focus

- -i: patient-focus, imperative; vocative, address for an elder kinship

- CV- -an: location

Syntax

Although originally a verb-initial language, Pazeh often uses SVO (verb-medial) sentence constructions due to influence from Chinese.

There are four case markers in Pazeh (Li 2000).

- ki Nominative

- ni Genitive

- di Locative

- u Oblique

Pazeh has the following negators (Li 2001:46).

- ini – no, not

- uzay – not

- kuang ~ kuah – not exist

- mayaw – not yet

- nah – not want

- ana – don't

Pronouns

The Pazeh personal pronouns below are from Li (2000). (Note: vis. = visible, prox. = proximal)

Remove ads

Vocabulary

Summarize

Perspective

Numerals

Pazeh and Saisiyat are the only Formosan languages that do not have a bipartite numerical system consisting of both human and non-human numerals (Li 2006).[19] Pazeh is also the only language that forms the numerals 6 to 9 by addition (However, Saisiyat, which is closely related to Pazeh, expresses the number 7 as 6 + 1, and 9 as 10 − 1.)

- 1 = ida adang

- 2 = dusa

- 3 = turu

- 4 = supat

- 5 = xasep

- 6 = 5 + 1 = xaseb-uza

- 7 = 5 + 2 = xaseb-i-dusa

- 8 = 5 + 3 = xaseb-i-turu

- 9 = 5 + 4 = xaseb-i-supat

The number "five" in Pazeh, xasep, is similar to Saisiyat Laseb, Taokas hasap, Babuza nahup, and Hoanya hasip (Li 2006). Li (2006) believes that the similarity is more likely because of borrowing rather than common origin. Laurent Sagart considers these numerals to be ancient retentions from Proto-Austronesian, but Paul Jen-kuei Li considers them to be local innovations. Unlike Pazeh, these Plains indigenous languages as well as the Atayalic languages use 2 × 4 to express the number 8. (The Atayalic languages as well as Thao also use 2 × 3 to express the number 6.) Saisiyat, Thao, Taokas, and Babuza use 10 − 1 to express 9, whereas Saisiyat uses 5 + 1 to express 6 as Pazeh does.[20] The Ilongot language of the Philippines also derives numerals in the same manner as Pazeh does (Blust 2009:273).[21]

Furthermore, numerals can function as both nouns and verbs in all Formosan languages, including Pazeh.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads