Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Period (music)

Musical unit of two interdependent phrases From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

In music theory, the term period refers to forms of repetition and contrast between adjacent small-scale formal structures such as phrases. In twentieth-century music scholarship, the term is usually used similarly to the definition in the Oxford Companion to Music: "a period consists of two phrases, antecedent and consequent, each of which begins with the same basic motif."[3] Earlier and later usages vary somewhat, but usually refer to notions of symmetry, difference, and an open section followed by a closure. The concept of a musical period originates in comparisons between music structure and rhetoric at least as early as the 16th century.[4]

Remove ads

Western art music

Summarize

Perspective

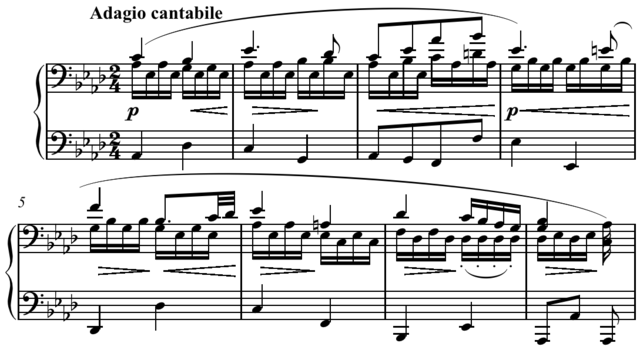

In Western art music or Classical music, a period is a group of phrases consisting usually of at least one antecedent phrase and one consequent phrase totaling about 8 bars in length (though this varies depending on meter and tempo). Generally, the antecedent ends in a weaker and the consequent in a stronger cadence; often, the antecedent ends in a half cadence while the consequent ends in an authentic cadence. Frequently, the consequent strongly parallels the antecedent, even sharing most of the material save the final bars. In other cases, the consequent may differ greatly (for example, the period in the beginning of the second movement of the Pathetique Sonata).

The 1958 Encyclopédie Fasquelle defines a period as follows:

Another definition is as follows:

- "In traditional music...a group of bars comprising a natural division of the melody; usually regarded as comprising two or more contrasting or complementary phrases and ending with a cadence." (Harvard Dictionary of Music, 1969)[9]

And

- "A period is a structure of two consecutive phrases, often built of similar or parallel melodic material, in which the first phrase gives the impression of asking a question which is answered by the second phrase."[1]

More recent definitions, especially by American theorists, have tightened the use of the term to restrict the contrast so that the first phrase must end in a half cadence or imperfect authentic cadence and the second a perfect authentic cadence.[10][11]

A double period is, "a group of at least four phrases...in which the first two phrases form the antecedent and the third and fourth phrases together form the consequent."[12]

When analyzing Classical music, contemporary music theorists usually employ a more specific formal definition, such as the following by William Caplin:

- "the period is normatively an eight-bar structure divided into two four-bar phrases. [...] the antecedent phrase of a period begins with a two-bar basic idea. [...] bars 3–4 of the antecedent phrase bring a 'contrasting idea' that leads to a weak cadence of some kind. [...] The consequent phrase of the period repeats the antecedent but concludes with a stronger cadence. More specifically, the basic idea 'returns' in bars 5–6 and then leads to a contrasting idea, which may or may not be based on that of the antecedent."[13]

Remove ads

Sub-Saharan music and music of the African diaspora

Summarize

Perspective

Bell patterns

The second definition of period in the New Harvard Dictionary of Music states: "A musical element that is in some way repeated," applying "to the units of any parameter of music that embody repetitions at any level."[15] In some sub-Saharan music and music of the African diaspora, the bell pattern embodies this definition of period.[16] The bell pattern (also known as a key pattern,[17][18] guide pattern,[19] phrasing referent,[20] timeline,[21] or asymmetrical timeline[22]) is repeated throughout the entire piece, and is one of the principal units of musical time for the ensemble, underlying the rhythms of accompaniment parts as well as melodies and improvisations.[23][24] The period is usually two or four main beats in length.[25][26][19] (See tresillo and cinquillo for examples of two-beat periods.) Four-beat periods may be represented in Western notation as a single bar, as in the examples given here; but see "Clave" below for an alternate presentation.

The seven-stroke "standard bell pattern" is one of the most commonly used musical periods in sub-Saharan music.[27] The first three strokes of the bell are antecedent, and the remaining four strokes are consequent. The consequent diametrically opposes the antecedent.[28][29]

Clave

Cuban clave is a well-known example of an African-derived periodic pattern in the New world. Cuban musicologist Emilio Grenet represents this rhythmic pattern as two bars of 2/4. However, in contemporary Latin music and in Latin jazz, it is usually written with two bars of 4/4, all of the note values doubled.

In explaining the structure of music guided by the five-stroke African bell pattern known in Cuba as clave (Spanish for 'key' or 'code'), Grenet uses what could be considered a definition of period: "We find that all its melodic design is constructed on a rhythmic pattern of two bars, as though both were only one, the first is antecedent, strong, and the second is consequent, weak."[30]

As Grenet and many others describe the period, the cross-rhythmic antecedent ('tresillo') is strong and the on-beat resolution is weak. This is the opposite of Western harmonic theory, where resolution is described as strong. Despite this difference, both the harmonic and rhythmic periods have consequent resolution. In simplest terms, that resolution occurs harmonically when the tonic is sounded, and in clave-based rhythm when the last main beat is sounded.[31] Metric consonance is achieved when the last stroke of clave coincides with the last main beat (last quarter note) of the consequent bar.[32]

The antecedent bar has three strokes and is called the three-side of clave. The consequent bar has two strokes and is called the two-side.[33] The three-side gives the impression of asking a question, which is answered by the two-side. The two sides of clave cycle in a type of repeating call and response.

[With] clave . . . the two bars are not at odds, but rather, they are balanced opposites like positive and negative, expansive and contractive or the poles of a magnet. As the pattern is repeated, an alternation from one polarity to the other takes place creating pulse and rhythmic drive. Were the pattern to be suddenly reversed, the rhythm would be destroyed as in a reversing of one magnet within a series . . . the patterns are held in place according to both the internal relationships between the drums and their relationship with clave . . . Should the drums fall out of clave (and in contemporary practice they sometimes do) the internal momentum of the rhythm will be dissipated and perhaps even broken—Amira and Cornelius (1992).[34]

Note that in most Cuban and Cuban-based popular music, such as salsa, the two halves of the pattern are reversed: the two-side is the precedent, the three-side the consequent. Please see the article on clave for a fuller explanation.

An actual key pattern does not need to be played in order for a key pattern to define the period. The concept and feel are so basic to the musical style that both musicians and listeners sense them even when not actually sounded. This should seem no more mysterious than Western audiences sensing a major scale without the musicians needing to play in note by note.[35][36]

Remove ads

See also

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads