Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

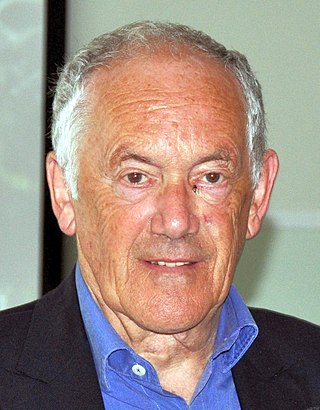

Peter Atkins

English chemist and author (born 1940) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Peter William Atkins FRSC (born 10 August 1940) is an English chemist and a Fellow of Lincoln College at the University of Oxford. He retired in 2007. He is a prolific writer of popular chemistry textbooks, including Physical Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry, and Molecular Quantum Mechanics. Atkins is also the author of a number of popular science books, including Atkins' Molecules, Galileo's Finger: The Ten Great Ideas of Science and On Being.

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Atkins left school (Dr Challoner's Grammar School, Amersham) at fifteen and took a job at Monsanto as a laboratory assistant. He studied for A-levels by himself and gained a place, following a last-minute interview, at the University of Leicester.

Atkins studied chemistry there, obtaining a BSc degree in chemistry, and a PhD degree in 1964 for research into electron spin resonance spectroscopy, and other aspects of theoretical chemistry. Atkins then took a postdoctoral position at UCLA as a Harkness Fellow of the Commonwealth fund.[1] He returned to Britain in 1965 as a fellow and tutor of Lincoln College, Oxford, and lecturer in physical chemistry (later, professor of physical chemistry). In 1969, he won the Royal Society of Chemistry's Meldola Medal. In 1996 he was awarded the Title of Distinction of Professor of Chemistry. He retired in 2007, and since then has been a full-time author.[2]

He has honorary doctorates from the University of Utrecht, the University of Leicester (where he sits on the university Court), Mendeleev University in Moscow, and Kazan State Technological University.

He was a member of the Council of the Royal Institution and the Royal Society of Chemistry. He was the founding chairman of IUPAC Committee on Chemistry Education, and is a trustee of a variety of charities.

Atkins has lectured in quantum mechanics, quantum chemistry, and thermodynamics courses (up to graduate level) at the University of Oxford. He is a patron of the Oxford University Scientific Society.

In 2016 Atkins received the James T. Grady-James H. Stack Award for Interpreting Chemistry for the Public from the American Chemical Society.[3]

Remove ads

Views on religion

Summarize

Perspective

Atkins is a well-known atheist.[4] He has written and spoken on issues of humanism, atheism, and conflicts between science and religion. According to Atkins, whereas religion scorns the power of human comprehension, science respects it.[5]

He was the first Senior Member of the Oxford University Secular Society, a Distinguished Supporter of Humanists UK (formerly known as the British Humanist Association) and an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society.[6] He is also a member of the advisory board of The Reason Project, a US-based charitable foundation devoted to spreading scientific knowledge and secular values in society. The organisation is led by fellow atheist and author Sam Harris. Atkins has regularly participated in debates with theists, including John Lennox,[7] Alister McGrath, Stephen C. Meyer, Hugh Ross,[8] William Lane Craig,[9][10] Rabbi Shmuley Boteach,[11] and Richard Swinburne.

In December 2006, Atkins was interviewed by journalist Rod Liddle in a UK television documentary on atheism called The Trouble with Atheism. In the documentary, Liddle asked Atkins: "Give me your views on the existence, or otherwise, of God." Atkins replied: "Well, it's fairly straightforward: There isn't one. And there's no evidence for one, no reason to believe that there is one, and so I don't believe that there is one. And I think that it is rather foolish that people do think that there is one."[12] In July 2016, Atkins was quoted as stating, “We are a hiccup on the way from one oblivion to another oblivion.”[13]

Atkins is known for his use of strident language in criticising religion: He appeared in the 2008 documentary-style film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed, in which he told interviewer Ben Stein that religion was "a fantasy" and "completely empty of any explanatory content. It is also evil".[14]

In 2007, Atkins's position on religion was described by Colin Tudge in an article in The Guardian as being non-scientific. In the same article, Atkins was also described as being "more hardline than Richard Dawkins", and of deliberately choosing to ignore Peter Medawar's famous adage that "Science is the art of the soluble".[15]

Remove ads

Personal life

Atkins married Judith Kearton in 1964 and they had one daughter, Juliet (born 1970). They divorced in 1983. In 1991, he married fellow scientist Susan Greenfield (later Baroness Greenfield). They divorced in 2005. In 2008, he married Patricia-Jean Nobes (née Brand).

Publications

General readers

- The Creation. W. H. Freeman & Co Ltd. 1981. ISBN 0-7167-1350-0.

- The Second Law. Scientific American Library, an imprint of W. H. Freeman and Company. 1984. ISBN 0-7167-5004-X

- Creation Revisited. W. H. Freeman & Co Ltd. 1993. ISBN 0-7167-4500-3.

- Second Law: Energy, Chaos, and Form. W. H. Freeman & Co Ltd. 1994. ISBN 0-7167-5005-8.

- The Periodic Kingdom: A journey into the land of the chemical elements. BasicBooks. 1995. ISBN 0-465-07266-6.

- Atkins' Molecules. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-521-53536-0.

- Galileo's Finger: The Ten Great Ideas of Science. Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-19-860941-8.

- Four Laws That Drive the Universe. Oxford University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-923236-9.

- The Laws of Thermodynamics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-957219-9.

- On Being: A Scientist's Exploration of the Great Questions of Existence. Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-960336-7.

- Reactions: The private life of atoms. Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-969512-6.

- What is Chemistry?. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-968398-7.[16]

- Physical Chemistry: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-968909-5.

- Chemistry: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-968397-0.

- Conjuring the Universe: The Origins of the Laws of Nature. Oxford University Press. 2018. Bibcode:2018cuol.book.....A.[17]

University textbooks

- Atkins, Peter W.; Symons, M. C. R. (1967). The Structure of Inorganic Radicals. Amsterdam, New York: Elsevier Pub. Co. OCLC 543225.

- Atkins, Peter W. (1991). Quanta: A Handbook of Concepts (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855573-5.

- Atkins, Peter W.; Beran, J. A. (1992). General Chemistry (2nd ed.). New York: Scientific American Books. ISBN 978-0716724964.

- Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio; Friedman, Ronald (2009). Quanta, Matter, and Change: A molecular approach to physical chemistry. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-6117-4.

- Atkins, Peter W.; Shriver, D. F. (2010). Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-1820-7.

- Atkins, Peter W.; Friedman, Ronald (2010). Molecular Quantum Mechanics (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199541423.

- Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio (2016). Elements of Physical Chemistry (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198727873.

- Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio (2022). Physical Chemistry (12th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198847816.

- Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio (2023). Physical Chemistry for the Life Sciences (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198830108.

- Atkins, Peter W.; Jones, Loretta (2023). Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight (8th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1319437930.

- Atkins, Peter W. (2024). Concepts in Physical Chemistry (2nd ed.). p. 394. doi:10.1039/9781837674244. ISBN 978-1-83767-386-5.

Remove ads

Media appearances

- Why Are We Here (Tern TV, 2017)

- Railways: The Making of a Nation – Food and Shopping (27 October 2016)

- Order & Disorder – The Story of Energy (16 October 2012)

- Horizon – What is One Degree? (10 January 2011) - Interviewed by Ben Miller

- Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed (18 April 2008)

- The Trouble with Atheism (18 December 2006)

Footnotes

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads