Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Phillips Brooks

American clergyman and author From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

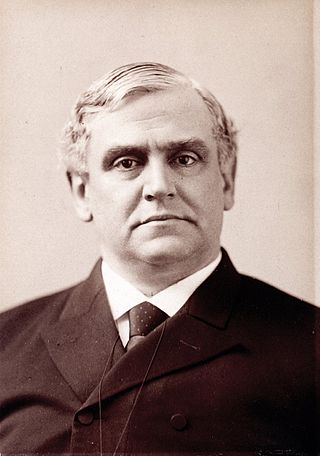

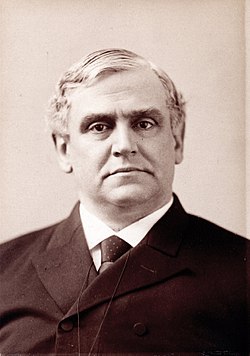

Phillips Brooks (December 13, 1835 – January 23, 1893) was an American Episcopal clergyman and author, long the rector of Boston's Trinity Church and briefly Bishop of Massachusetts. One of the most popular preachers of the Gilded Age, he worked to make the Christian Church more relevant to contemporaries.[1] Among his other accomplishments, he wrote the lyrics of the Christmas hymn "O Little Town of Bethlehem".

He is honored on the Episcopal Church liturgical calendar on January 23.[2] In addition to his moral stature, he was a man of great physical height, standing six feet four inches (1.93 m) tall.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Early life and education

Brooks was born on December 13, 1835, in Boston to William Gray Brooks and Mary Ann Phillips Brooks. His father, a Unitarian from a solid, middle-class background, started his career as a hardware and dry goods merchant. His mother was from an orthodox Congregational family. Her father was John Phillips (1776-1820), one of the founders of Andover Theological Seminary.[1]

Rejecting the arid Unitarianism of New England, Mary Ann Brooks determined that the family would join St. Paul's Episcopal Church on Tremont St. in Boston.[1] Three of Phillips Brooks' five brothers – Frederic, Arthur, and John Cotton – were eventually ordained in the Episcopal Church.

Phillips Brooks attended Boston Latin School, where he excelled in classical languages, followed by Harvard University. Here, he encountered literary Romanticism, the sermons of Henry Ward Beecher, and the poetry of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He was elected to the A.D. Club and graduated in 1855 at the age of twenty.

After graduation, he took a post at Boston Latin where he lasted only six months before being fired. He felt that he had failed miserably. He wrote, "I do not know what will become of me and I do not care much.... I wish I were fifteen years old again. I believe I might become a stunning man: but somehow or other I do not seem in the way to come to much now."[3]

Brooks chose to enter the ministry. In 1856, he began to study for ordination in the Episcopal Church in the Virginia Theological Seminary at Alexandria, Virginia. He struggled with what he perceived as anti-intellectualism of his fellow students but managed to complete his training.[1] While a seminarian there, he preached at Sharon Chapel (now All Saints Episcopal Church, Sharon Chapel) in nearby Fairfax County.

Remove ads

Pastoral career

Summarize

Perspective

Philadelphia during the Civil War

In 1859, Brooks graduated from Virginia Theological Seminary, was ordained deacon by Bishop William Meade of Virginia, and became rector of the Church of the Advent in Philadelphia. In 1860, he was ordained priest, and in 1862, became rector of the Church of the Holy Trinity, Philadelphia, where he remained seven years, gaining an increasing name as a Broad churchman,[4] preacher, and patriot.

During the American Civil War he upheld the cause of the North and opposed slavery, and his sermon on the death of Abraham Lincoln was an eloquent expression of the character of both men. His sermon at Harvard's commemoration of the Civil War dead in 1865 likewise attracted attention nationwide.[4]

Trinity Church, Boston

In 1869, Brooks accepted the call to serve as rector of Trinity Church, Boston; today, his statue is located on the left exterior of the church.

Brooks' ambition was to help build a new kind of Protestantism that incorporated insights drawn from the Romantic and liberal theology of the nineteenth century, particularly its celebration of subjective individual experience. To this end, he worked to create a physical manifestation of that message in stone and mortar.[1]

In the 1870s, Brooks became intimately involved in the design and construction of the new Trinity Church on Copley Square in the Back Bay. Architect Henry Hobson Richardson drew on Romanesque architectural language to create an architectural masterpiece. The interior was richly decorated with murals by John LaFarge and stained glass windows by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. A repudiation of the cool, classical aesthetic of New England Protestantism, the church was designed to evoke religious sensibilities in the congregation. Van Wyck Brooks wrote that the new church represented "the break of the Boston mind with its Puritan past."[5]

The interior marked a deliberate return to early Christian liturgical principles and symbolism. Among the building's notable features was a freestanding liturgical altar. This allowed the celebrant to face the congregation during the Eucharist, emphasizing the communal nature of the sacrament rather than the priest acting as intermediary between God and people. The church also had a synthronon, a semicircular seating arrangement for priests around the apse that directly mirrors early Christian basilicas. Theologically, it represents the collegiality of the priesthood, the idea that ministry is shared among clergy rather than concentrated in a single hierarchical figure. With no choir stalls blocking sight lines, the entire assembly could participate more fully in the liturgy.[6] These interior features were inspired by St. George's Episcopal Church (Manhattan).[7]

Until 1888, Trinity Church had no pulpit. Brooks preferred to preach his legendary sermons from a modest lectern near the rector's stall on the south side of the chancel. By preaching from within the chancel rather than from a towering pulpit, Brooke embodied the Anglican via media between Catholic sacramentalism and the Protestant emphasis on preaching.[6]

Such was the magnificence of Trinity Church that historian Douglass Shand-Tucci called it "an American Hagia Sophia."[8]

Preaching

Brooks was a gifted preacher with broad appeal. His sermons drew crowds of people, some of whom had never been in an Episcopal Church before. He had no sensational manner, according to listeners, but simply presented the Gospel in his natural style. "There is nothing in his voice, bearing, or look," wrote one frustrated observer, "which can explain his almost unexampled popularity. For popular he is almost beyond precedent."[1]

One source of his power as a speaker, according to historian Gillis J. Harp, was his ability to offer congregants an encounter with Christ through a mixture of scriptural truth and personality. Skilled at the use of metaphor to quicken religious sentiment, he was both preacher and poet.[1]

Brooks was neither a reformer nor a social conservative, but both groups drew inspiration from his words. Harp noted, "He understood his own ministerial role as primarily exhortative, an inspirational preacher to stir ups he soul, not agitate for social change."[1]

Bishop of Massachusetts

On April 30, 1891, Brooks was elected sixth Bishop of Massachusetts, despite opposition from conservative High Church Anglo-Catholics opposed to his theological liberalism.[1] He was consecrated to that office in Trinity Church on October 14, 1891.

Brooks was for many years an overseer and preacher of Harvard University. In 1881, he declined an invitation to be the sole preacher to the university and professor of Christian ethics.

Remove ads

Death

Brooks died suddenly in early 1893, at the age of fifty-seven, probably as a result of diphtheria complicated by a cold or flu. His episcopate lasted only 15 months.[1]

His death was a major event in the history of Boston. One observer reported: "They buried him like a king. Harvard students carried his body on their shoulders. All barriers of denomination were down. Roman Catholics and Unitarians felt that a great man had fallen in Israel."[9]

Somewhat more critically, Harvard professor Charles Eliot Norton noted that Brooks seldom appeared to be troubled by religious doubt or concern about the declining influence of the clergy. "He was quite sincere, for religion was a matter of sentiment not of intelligence with him. His strong sense of right & wrong prevented his optimism from sapping his moral integrity, and from doing much harm to the easygoing public whom he served and pleased. The eulogies of him are sadly extravagant."[1]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Publications

Brooks left behind published lectures and sermons in an effort to bring Protestant Christianity to a wide audience of readers. In 1877, Brooks published a course of lectures upon preaching that he had delivered at the theological school of Yale University as an expression of his own experience. In 1879, the Bohlen Lectures on The Influence of Jesus came out. In 1878, he published his first volume of sermons, and from time to time issued other volumes, including Sermons Preached in English Churches (1883) and "The Candle of the Lord" and Other Sermons (1895).

Brooks was also famous and beloved for his collections of sermons, The Purpose and Use of Comfort, first published in 1878, which includes the title sermon as well as: "The Withheld Completions of Life," "The Conqueror from Edom," "Keeping the Faith," "The Soul's Refuge in God," "The Man with One Talent," "The Food of Man, "The Symbol and the Reality," "Is It I?", and others.

He wrote several hymns and carols, among them the Christmas carol "O Little Town of Bethlehem".[10]

Influence

Brooks did not marry or have children of his own, but he had great love for children. He met an eleven-year-old Helen Keller when she was at the Perkins Institute for the Blind. It is said that "she sat on Phillips Brooks' knee and learned that God is love."[11]

Awards and Monuments

Within his lifetime, Brooks received honorary degrees from Harvard (1877) and Columbia (1887), and the Doctor of Divinity degree by the University of Oxford, England (1885).

His close ties with Harvard University led to the creation of Phillips Brooks House in Harvard Yard, built seven years after his death. On January 23, 1900, it was dedicated to serve "the ideal of piety, charity, and hospitality". The Phillips Brooks House originally housed a Social Service Committee, which became the Phillips Brooks House Association in 1904. It ceased formal religious affiliation in the 1920s, but remains in operation as a student-run group of volunteer organizations. Brooks' theological alma mater, Virginia Theological Seminary, honors him with a statue outside its library.[12]

A statue of Phillips Brooks stands on the North Andover, Massachusetts, Town Common, facing North Parish Church.

A private elementary school in Menlo Park, California – Phillips Brooks School – is named for him, as is Brooks School in his hometown of North Andover, Massachusetts, the latter founded by Endicott Peabody, who also founded the Groton School. The Brooks family founded a Brooks Memorial School in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1874 in memory of Phillips' brother, the Rev. Frederic Brooks, who died in an accident in Cambridge. That school was sponsored in part by John D. Rockefeller and operated under the Brooks name until 1891; it currently operates under the name of the Hathaway Brown School. John S. White, first headmaster of the school in Cleveland, also founded a Phillips Brooks School in Philadelphia in 1904 that operated there until 1919.

The Episcopal Church remembers Phillips Brooks annually on January 23, the anniversary of his death.[2] He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[13][14]

Remove ads

Notes

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads