Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Preludes, Op. 23 (Rachmaninoff)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

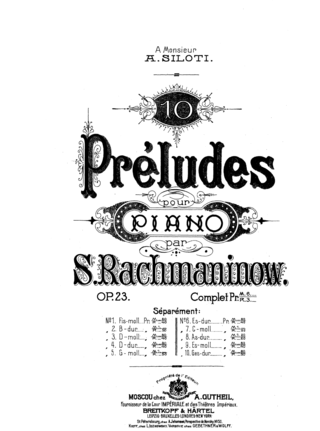

Ten Preludes, Op. 23, is a set of ten preludes for solo piano, composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1901 and 1903. This set includes the famous Prelude in G minor.

Together with the Prelude in C♯ minor, Op. 3/2 and the 13 Preludes, Op. 32, this set is part of a full suite of 24 preludes in all the major and minor keys.

Remove ads

Composition

Op. 23 is composed of ten preludes, ranging from two to five minutes in length. Combined, the pieces take around thirty minutes to perform. They are:

- No. 1 in F♯ minor (Largo)

- No. 2 in B♭ major (Maestoso)

- No. 3 in D minor (Tempo di minuetto)

- No. 4 in D major (Andante cantabile)

- No. 5 in G minor (Alla marcia)

- No. 6 in E♭ major (Andante)

- No. 7 in C minor (Allegro)

- No. 8 in A♭ major (Allegro vivace)

- No. 9 in E♭ minor (Presto)

- No. 10 in G♭ major (Largo)

Rachmaninoff composed Prelude No. 5 in 1901. The remaining preludes were completed after Rachmaninoff's marriage to his cousin Natalia Satina, with nos. 1, 4, and 10 being premiered in Moscow on February 10, 1903, and the remaining seven being completed soon thereafter.[1] The years 1900–1903 were difficult for Rachmaninoff, and his motivation for writing the Preludes was predominantly financial.[2] Rachmaninoff composed the works while living in the Hotel America as a guest of his cousin Alexander Siloti, and he dedicated the set to Siloti in gratitude.

Remove ads

Analysis

Summarize

Perspective

Rachmaninoff's Ten Preludes abandon the traditional short prelude form employed by composers such as Bach, Scriabin, and Chopin. Unlike Chopin's set, some of which are little more than half-page musical fragments, Rachmaninoff's Ten Preludes last for several minutes each, and have complex and expansive multi-sectional forms.[2] Written when the innovations of serialism were only a few short years away, they perhaps represent a last flowering of the Romantic idiom.[3] The set reflects Rachmaninoff's experience as a virtuoso pianist and master composer, testing the "...technical, tonal, harmonic, rhythmic, lyrical, and percussive capabilities of the piano."[3]

Of the comparative popularity of his Ten Preludes and his early Prelude in C♯ minor, Op. 3, No. 2, a favourite of audiences, Rachmaninoff remarked: "...I think the Preludes of Op. 23 are far better music than my first Prelude, but the public has shown no disposition to share in my belief...."[4] The composer never played all of the Preludes in one sitting, instead performing selections of them, consisting of preludes from both his Op. 23 and Op. 32 sets which were of contrasting character.[5] Nonetheless, certain characteristics of the work, such as adjacent preludes sharing common chords or having tonalities a step apart, and the "bookend" relationship between the first and last preludes (both marked Largo, with the last in the parallel major of the first), suggest that the sets were intended by the composer as coherent units, and that he envisioned the potential of complete performances. Together with Op. 32 and Op. 3, Rachmaninoff's Preludes represent all twenty-four major and minor keys.[6]

From a performance standpoint, the ten Op. 23 Preludes vary widely in difficulty. Nos. 1, 4, 5, and 10 are conceivably within reach of the "advanced-intermediate" pianist, while nos. 2 - 3 and 6 - 9 (particularly no. 9) demand a higher degree of endurance and dexterity.[3] Nonetheless, even the "easier" preludes require great skill in voicing, articulation, dynamic control, and the shaping of long phrases, putting true mastery of the pieces beyond the reach of all but virtuosi.[3]

Remove ads

Reception

The Ten Preludes, along with the Op. 3 prelude and the Thirteen Preludes of Op. 32, are considered to be among Rachmaninoff's best works for solo piano.[3] The "Russian" quality of the Op. 23 preludes is often noted by listeners: after hearing Boris Asafyev play the preludes, the painter Ilya Repin noted a streak of Russian nationalism and originality in rhythm and melody. At the same recital, Vladimir Stasov praised the characteristic "Rachmaninoff sound" and unusual and innovative bell-like quality of the pieces, and Maxim Gorky simply noted, "How well he hears the silence."[3]

Music editions

Most editions of the Op. 23 Preludes contain significant editorial distortions in dynamics and phrasing. In 1986, Ruth Laredo set out to produce the first authentic version but was unable to obtain the original manuscripts. The Piano Quarterly praised Laredo's editorial practices, remarking that, "this seems to be the edition to own."

However, in 1992, Boosey & Hawkes published an edition edited by Robert Threlfall, who had managed to obtain access to the original manuscripts. This edition is widely regarded as the first truly authentic version.[7]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads