Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Protect and Survive

1974–1980 UK public information campaign From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

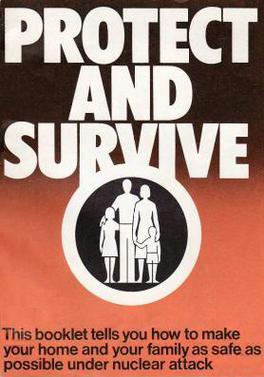

Protect and Survive was a public information campaign on civil defence. Produced by the British government between 1974 and 1980, it intended to advise the public on how to protect themselves during a nuclear attack. The campaign comprised a pamphlet, newspaper advertisements, radio broadcasts, and public information films. The series had originally been intended for distribution only in the event of dire national emergency, but provoked such intense public interest that the pamphlet was published, in slightly amended form, in 1980. Due to its controversial subject, and the nature of its publication, the cultural impact of Protect and Survive was greater and longer-lasting than most public information campaigns.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

Protect and Survive had its origins in civil defence leaflets dating back to 1938, titled The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids.[1] These advised the homeowner on what to do in the event of air attack. This evolved as the nature of warfare and geopolitics changed, with the pamphlets updated first into The Hydrogen Bomb in 1957, and later into Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack in 1963.[2][3] This document, of which 500,000 copies were made, garnered considerable public and government criticism when it was first released for its lack of explanations or conveyance of the reasoning behind the advice that was given. The Estimates Committee were similarly bemused by the advice, calling for its withdrawal. Civil defence personnel were summoned to House of Commons meetings in which they responded to all the points of criticism that were raised.[4] The 1963 pamphlet was then accompanied by a series of public information films produced in 1964, called Civil Defence Information Bulletins. These films were intended to be broadcast in a state of emergency. Pamphlets similar to those prepared in 1963 briefly appeared in Peter Watkins' controversial 1965 BBC pseudo-documentary The War Game, in a scene where they were distributed to people's homes. The 1964 bulletins were not depicted in the film.

The fallout radiation advice in Protect and Survive was based on 1960s fallout shelter experiments[5] summarised by Daniel T. Jones of the Home Office Scientific Advisory Branch[6] in his report, The Protection Against Fallout Radiation Afforded by Core Shelters in a Typical British House which was published in Protective Structures for Civilian Populations, Proceedings of the Symposium held at Washington, D.C., 19–23 April 1965, by the Subcommittee on Protective Structures, Advisory Committee on Civil Defense, US National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council.[1][7] The fallout radiation was represented by measurements of the penetration of cobalt-60 gamma radiation, which has a high mean energy of 1.25 MeV (two gamma rays, 1.17 and 1.33 MeV). This is considerably more penetrating than the mean 0.7 MeV of fallout gamma rays.[1] Therefore, the actual protection given against real nuclear weapon fallout would be far greater than that afforded in the peacetime cobalt-60 shielding measurements.

Wartime Broadcasting Service

During the early 1970s, the BBC and the Home Office produced a radio script advising the public of what to do in the event of nuclear attack. This was eventually published in October 2008 on the BBC's website,[8] with the full correspondence made available to the public via The National Archives.[9][10] The script used very similar language and style to the later Protect and Survive series. In particular, it emphasised the need for citizens to remain in their homes,[8] and not to try to evacuate elsewhere.

During the exchange of correspondence between the BBC and various government departments, several letters seem to suggest that a booklet for public consumption was already being discussed. In a letter[11] from the Central Office of Information, dated 12 March 1974, a request for information from The Home Office about a proposed booklet read as follows:[12]

Meanwhile I should be grateful if you could let me have a copy of your revised advice to the householder. I will assume that this will form the text of the Official Announcement and that what Probert is discussing with your Information Division is the production of a booklet on public advice.

This was replied to on 15 March 1974 by the Home Office, clearly stating that such a booklet was being produced, and that they were also targeting the same information at television:[12]

It seems likely a basic booklet will be produced... we expect rather more attention to be paid to the dissemination of this advice through other media, in particular television.

Remove ads

Campaign

Summarize

Perspective

The purpose of the Protect and Survive scheme was to provide members of the British public with instructions, primarily via broadcast media, on how to protect themselves and survive a nuclear attack. The broadcasts were to be supplemented by a pamphlet which was to act as an aide-memoire for householders; despite the pamphlet's later prominence in British culture, the campaign was originally conceived as being broadcast-led, with the pamphlet being confirmed later.[13] The scheme was not intended to be made public during peacetime, and would only have been broadcast if a nuclear attack was deemed likely by the Government during an international crisis. The information detailed a series of steps recommended to be undertaken by British civilians to improve their chances of survival in the event of a nuclear strike on the United Kingdom.

Basic advice

The following advice was common to all components of the campaign, but is presented here according to the ordering contained in the pamphlet.

Nuclear weapon effects

It was explained that everything within a certain radius of a nuclear explosion would be destroyed, and that the heat and blast effects would be extremely destructive for the first five miles and could still cause severe damage beyond this. The formation of and risk from radioactive fallout was also explained.[14][15]

Household shelters

The advice on preparing a shelter at home caused much of Protect and Survive's later infamy.[13][16][17] The campaign aimed to convince people of the importance of staying at home instead of self-evacuating elsewhere on the basis that one's local authority would offer the best help.[18][15] It then sought to explain how best to prepare one's home for use as a post-attack shelter centred around a "fallout room"[nb 1] intended for fourteen days' use.[20] Ideally, a cellar or basement would be used as the fallout room; if not, householders were to use a ground-floor area which was as far away from the roof and outside walls (or at least had the smallest amount of outside wall) as possible.[14] To reduce the risk from radiation, windows and other openings were to be blocked up and the floor and outside walls made thicker; bricks, concrete blocks, timber, boxes of earth or sand, books, and furniture were recommended as examples of the thick and dense materials to be used.[16][14]

Once the basic fallout room had been prepared, it was to be followed by an inner refuge for additional protection during the first forty-eight hours following an attack. Recommendations included:[15]

- Making a lean-to from strong boarding or from doors taken from upper rooms (with some wood fixed to the floor to secure the construction) which was then reinforced with bags or boxes containing earth, sand, books, or even clothing, and the two open ends partly walled in with similar boxes or with heavy furniture[16][21]

- Using a sufficiently large table or tables,[22] to be surrounded and covered with heavy furniture filled with sand, earth, books, or clothing

- Reinforcing the stair cupboard[20] with bags of sand or earth on the stairs and along the wall of the cupboard (as well as any adjacent outside wall)

Provisions were to be sufficient to last the prescribed fourteen days.[22][16] It was recommended to stock three and a half gallons of drinking water per person,[20] and to then double this amount to have sufficient provision for washing. The water was to be bottled for immediate use in the fallout room,[15] with additional supplies to be contained in the bath, basins, and other containers,[20] and all of this sealed or covered against fallout.[15] The fallout room was to be stocked with foods which could be "eaten cold, which keep fresh, and which are tinned or well wrapped", and which were to be kept in a closed cabinet or cupboard; it was recommended to maintain a variety of foods including sugar, jams, and other sweet foods, cereals, biscuits, meats, vegetables, and fruits and fruit juices. Children would need tinned or powdered milk and babies "their normal food as far as is possible."[15] These provisions were to be accompanied by tin and bottle openers,[22] cutlery, and crockery.[15] In the "Food Consumption" film, it was stated that only minimal eating was needed since householders would normally be resting under shelter;[21] those reading the pamphlet were merely told to eat sparingly.[15] Whether people would have been able to acquire fourteen days' worth of provisions if the Protect and Survive advice had been issued for real was disputed at official level,[23] let alone unofficially.[24]

A battery-powered radio would have been essential for receiving outside messages, and it was recommended to take a spare radio in addition to batteries; aerials were not to be extended until an attack was concluded to avoid electromagnetic pulse damage.[25] The basic "survival kit" was rounded off with stocks of warm clothing[15] and a copy of the Protect and Survive pamphlet. In terms of additional provisions, the following items were all described as useful:[15]

- Bedding and sleeping bags

- Saucepans and portable stoves with fuel

- Torches with spare bulbs and batteries, candles, and matches

- A table with chairs

- Toilet articles, soap, toilet rolls, buckets, and plastic bags (see also the following paragraph on sanitation)

- Changes of basic clothing

- A first aid kit and medicines[26]

- Sand, cloths, or tissues for wiping down plates and utensils

- A notebook and pencils for writing messages

- Brushes, shovels, cleaning materials, rubber or plastic gloves, and a dustpan and brush

- Toys and magazines

- A mechanical clock and a calendar

Special toilet arrangements needed to be made in order to conserve water. Toilet articles had already been mentioned in the provisions list (see above), and were mentioned again in relation to sanitation; the buckets or other containers were to be covered and fitted with bag liners, and if possible a chair should be improvised as a toilet seat.[26][18] A disinfectant solution was also to be kept. A dustbin for toilet waste was to be kept just outside the fallout room; all other waste was to be either put in a separate dustbin if available or put in plastic bags or paper until it could be taken outside the house.

Though the heat flash was claimed to be incapable of igniting the bricks and stone of a then-typical British house, internal contents could be ignited if windows were left unprotected. It was therefore advised to remove easily ignited articles from the attic and upper rooms (with fires being judged to be most likely in those areas), net curtains or thin materials from windows (but not heavy curtains and blinds since these would provide protection against flying glass), old newspapers and magazines, and boxes, firewood, and easily ignited materials from the outside of the house. Windows, including glass panes, were to be coated with light-coloured paint so that they would reflect away the heat flash even if the subsequent blast wave was to shatter them.[16][22] Buckets of water were to be kept on each floor, and a fire extinguisher was ideal. Doors, or at least those that had not been used for making the lean-to variety of inner refuge, were to be closed to help prevent the spread of fire. The fire hazard from damaged gas, oil, and elecriticity supplies, and the resulting need to know where and how to turn these off, was stressed.

The suitability of different types of housing stock was assessed. Those living in a block of flats were to avoid the top two floors and make alternative shelter arrangements (five storeys or more) or to shelter in the basement or the ground floor (up to four storeys). Single-storey homes such as bungalows were described as ill-suited for shelter purposes; if a shelter had to be made in such a building, householders were to select a place that was furthest away from the roof and outside walls as described earlier.[15] Those living in caravans or similar accommodation were to be advised on what to do by local authorities.[27]

Warnings and actions on warning

The various warning signals were explained (and, in the films, were accompanied by recordings of how they would sound). An attack warning would involve sirens sounding a rising and falling note as well as warnings delivered via radio. A fallout warning would involve three loud bangs (from maroon rockets), gongs, or whistles in quick succession.[28] When the immediate danger had passed, sirens would sound the all-clear with a steady note.[29]

On hearing the attack warning, people who were already at home (or could reach it within "a couple of minutes") were to send any children to the fallout room first, turn off gas, electricity, and oil supplies as described earlier, close stoves and damp down other fires, shut their windows and draw the curtains, and finally go to the fallout room. Those who could not reach their homes were to take cover in nearby buildings if they were not already indoors, or to take any other kind of cover if they could not reach a building in time, including lying flat in a ditch and covering up their hands and head.[20]

It was claimed that once an attack had ended there would be a short period before fallout started to descend; during this time, mains water was to be used for firefighting and for topping up water reserves, and then turned off. If the water supply was externally interrupted, water heaters and boilers (including hearth fires with back boilers) were to be extinguished and taps turned off. Fuel supplies were to be turned off if this had not been already done. Toilets were to be left unflushed and were to have their chains removed and their handles taped up in order to preserve the water in their cisterns.[20] Any structural damage was to be countered by using curtains or sheets to cover up holes and broken windows.[28] The survival kit was to be kept at hand if it was not already in the fallout room. Neighbours could be helped if the fallout warning had yet to be sounded.[28]

On hearing the fallout warning, those who were outdoors were to take indoors cover as soon as possible and wipe off as much dust from themselves as they could before entering, while those at home were to go to the fallout room if they had not done so already and stay inside the inner refuge for the next forty-eight hours. After this time had elapsed, the radiation risk would have lessened, but it was stressed that exposure could still be lethal and that people should remain at home until told via radio that it was safe to leave.

Once the fallout risk was acceptably low, the house could initially be left for a few minutes to complete essential tasks (to be done by those aged over thirty if possible). To avoid bringing radioactive dust into the house, footwear was to be wiped down between excursions, and ideally separate outdoor footwear would be kept.

If there were casualties from an attack, the household would have had to provide initial medical help. The radio was to be monitored for information on such medical services and facilities as might be available and on which cases were to be treated as urgent.[26] If anyone died while in the fallout room, their body was to be placed in another room and covered as securely as possible with an attached identification (in the relevant film, separate identifications were to be attached to both the body and its covering[21]). If no instructions were issued within five days on what to do next, the body was to be buried in a temporary grave as soon as it was safe to leave the house.[27][26][18] These instructions for bodily disposal would be a further source of the infamy attached to Protect and Survive.[30][31][16]

Once the all clear had been sounded, there would no longer be any immediate danger and so, in theory at least, normal activities could be resumed.[32]

The Protect and Survive pamphlet was prepared in 1976, and some 2,000 copies were printed and secretly issued to chief executives of local authorities and senior police officers. Its existence having been brought to public attention by the Times (see below), a slightly revised edition was printed in 1980 and made available through Stationery Office bookshops.[13] This peacetime publication of the pamphlet was priced at 50 pence,[33] but it was intended for free distribution to all British households should a crisis period develop.[34] The contents of the pamphlet would also be printed in national newspapers if the risk of nuclear attack increased, with printers' proofs of this version being prepared beforehand.[13][35]

Early drafts featured what Taras Young called "clumsy choices"; the stay-at-home language included a statement that "only fools run away", while drawings for the inner refuge showed it being prepared with cushions and mattresses rather than the bulkier items of the final version. The Central Office of Information expressed concern that the "Deaths" section would be unduly worrying; the heading was thus removed and the information folded into the "Casualties" section.[13] Radios were to be merely switched off to (ineffectively) ward against electromagnetic pulse damage rather than the final version's more effective advice of leaving the aerial disconnected or unextended.[36]

The main pamphlet was complemented in 1981 by two publications regarding the construction of fallout shelters: an A5 pamphlet called Domestic Nuclear Shelters with techniques for building a home shelter, and an A4 book called Domestic Nuclear Shelters – Technical Guidance for the design and construction of long-term and permanent shelters, some of which involved elaborate designs. The A5 pamphlet was later described as "neither flesh nor fowl" in a 1986 memorandum, and as early as 1983 it was felt that the information therein should instead be incorporated into a future revision of Protect and Survive. One of the shelters described in both Domestic Nuclear Shelters publications was essentially identical to the Second World War-era Morrison shelter, with assembly instructions being little changed from those presented in a 1941 pamphlet for the same;[37][38] another type of shelter was based on the Anderson shelter, also of Second World War vintage.[39][40] Like the main Protect and Survive pamphlet, the A5 Domestic Nuclear Shelters pamphlet was priced at 50 pence;[38] the Technical Guidance book was priced at £5.95.

In response to extensive criticism of Protect and Survive, a follow-up pamphlet entitled Civil Defence: Why we need it was published in November 1981 which attempted to defend the government's approach to civil defence.[41][38][42]

One final pamphlet, Nuclear Weapons, did not carry Protect and Survive branding (and, indeed, had been first published in 1956[43]), but an updated version was published in the same year as the main Protect and Survive pamphlet and has been referred to alongside the other pamphlets. This pamphlet contained a more technical discussion of nuclear weapon effects and countermeasures.[38]

Publication of the pamphlet

Protect and Survive was formally published in May 1980, but had come to the public's attention before that via a series of articles in The Times newspaper in January 1980.[44] This wave of interest had been preceded by numerous letters to The Times in December 1979[45][46] questioning what Civil Defence arrangements were in place in the UK.

This was then followed by a Times leader on 19 January 1980 which noted that: "In Britain, a Home Office booklet "Protect and Survive" remains unavailable."[47] Following this unexpected publicity for Protect and Survive, The Minister of State at the Home Office, Leon Brittan, responding on the subject in the House of Commons on 20 February 1980 said that:[48]

...attention has been focused on the decision of the Home Office not to publish, in advance of an imminent attack, the pamphlet entitled "Protect and Survive". It is not a secret pamphlet, and there is no mystery about it. It has been available to all local authorities and chief police and fire officers and to those who have attended courses at the Home Defence College at Easingwold. It has been shown to interested members of parliament and to journalists. It has not been published, for the simple reason that it was produced for distribution at a time of grave international crisis when war seemed imminent, and it was calculated that it would have the greatest impact if distributed then.[49]

The Minister then went on to say the Home Office had received over two hundred letters from the public on civil defence. Following the press and parliamentary focus on Protect and Survive, as well as an episode of the BBC's Newsnight programme which focused on the campaign, the government chose to publish the pamphlet in May 1980.[13]

Television

Protect and Survive was adapted for television as a series of twenty short public information films. The films were classified, intended for transmission on all television channels if the government determined that nuclear attack was likely within 72 hours. However, recordings leaked to CND and the BBC, who broadcast excerpts from them on Panorama on 10 March 1980, shortly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[50]

The films were produced by Richard Taylor Cartoons, who also produced the Charley Says child safety films and children's animation Crystal Tipps and Alistair,[13] and were ready for use by at least 1975,[51] with rough cuts being screened at the Central Office of Information in November of that year.[13] They were similar in content to the pamphlet, detailing the same instructions using voice-over narration, sound effects, and a combination of simple stop-motion and illustrated animation. Patrick Allen was chosen to narrate. His voiceover was later described as "the calm, clipped vowels of a male announcer, advising how to build shelters, avoid fallout, and wrap up your dead loved ones in polythene, bury them, and tag their bodies." He later parodied the recordings for Frankie Goes To Hollywood's song "Two Tribes", announcing "Mine is the last voice you will ever hear. Do not be alarmed".[33]

Each episode concluded with a distinctive electronic musical phrase composed by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's Roger Limb. It featured two high- and low-pitched melodies coming together "like people". So great was the secrecy around production that Limb handed over his tapes to producer Bruce Allen in an alley.[33]

The "Refuges" film was originally meant to cover outdoor bunkers as well as indoor shelters but the relevant scenes were cut;[53] the subject of outdoor shelters was later covered in the Domestic Nuclear Shelters series of publications.[37]

Radio

A collection of recordings for radio transmission were produced as part of the programme: they differ slightly from the films in that the voice was provided not by Patrick Allen, but by both male and female voices. In addition, certain portions of the instructional copy are changed slightly, and there is an extra part on preparing a first aid kit.[54] While it has been speculated[by whom?] that small portions of these recordings is heard in Threads, such as during the scene where the character of Bill Kemp is discussing removing internal doors to use for their shelter, they are in fact either re-recorded by an actor or extracted from the public information films.

Remove ads

Political reaction

Summarize

Perspective

Being published in peacetime and outside of its intended context as a supplement to the broadcast campaign, the Protect and Survive pamphlet "seemed at once sinister and quite pathetic" and was rendered incapable of being taken seriously.[13] Organisations such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament protested that the pamphlet, by popularising the idea that a nuclear war could be survived, made such a war more likely. The protest organisations published and sold large numbers of copies of the pamphlet, considering that widespread reading of the pamphlet could only discredit the government's policy. Counter-pamphlets such as "Protest and Survive" by Edward Palmer Thompson[55] and "Civil Defence, whose Defence" by the Disarmament Information Group[56] intended to debunk the pamphlet's arguments. In 1983, some press attention was drawn to an experiment by Ben Hayden, a member of Tower Hamlets CND, who decided to build a shelter in accordance with the Protect and Survive instructions and live there for the prescribed two weeks;[39] Hayden would later publish a book (Ben's Bunker Book) about his experiment, with its presentation mimicking that of the Protect and Survive pamphlet.[55]

Protect and Survive was referred to by name in the 1980 Square Leg exercise scenario[34] and in an initial draft of the 1982 Hard Rock exercise scenario; later versions of the Hard Rock scenario referred to it as "Public, Do-It-Yourself Civil Defence" instead, which Duncan Campbell interpreted as a sign that the Protect and Survive brand had become internally embarrassing for the Home Office.[57][58] These and other civil defence exercises also assumed that significant numbers of people would self-evacuate from perceived target areas despite the stay-at-home instructions given in Protect and Survive and other official communiques.[34][59][57]

A 1981 paper by Sid Butler, the Deputy Director of the Home Office Scientific Advisory Branch, analysed three different attack scenarios and the expected death toll if the stay-at-home advice was followed as compared to if the advice was ignored and people dispersed themselves; in all three scenarios, there were more immediate survivors as a result of self-dispersal. In the case of an attack "primarily on civilian targets", the paper predicted that the additional death toll which would be incurred by strict adherence to the stay-at-home advice would be in the region of 12 million.[60]

Remove ads

Cultural impact

Summarize

Perspective

The Protect and Survive campaign had a substantial impact on British popular culture in the early 1980s. Owing to the controversy surrounding the campaign, much of this cultural response was "barbed".[13]

In music, rock band Jethro Tull recorded a song called "Protect and Survive" on their 1980 album A, while the hardcore punk/D-beat band Discharge recorded the track "Protest and Survive", named after Edward Palmer Thompson's anti-nuclear manifesto, for their 1982 album Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing. Actor Patrick Allen, who narrated the associated public information films, recreated this narration for the 1984 number one single, "Two Tribes", by Frankie Goes To Hollywood. Irish folk band The Dubliners recorded a song called “Protect and Survive” on their 1987 record, 25 Years Celebration. Heavy metal band Wolfsbane's self-titled 1994 album contains a song called "Protect and Survive". More recently, the campaign's logo and illustrations from the pamphlet can be seen on the cover of the 1997 "Karma Police" single by Radiohead. Also, London post-rock band Public Service Broadcasting recorded the track "Protect and Survive" using samples from the Roger Limb score set over a drum-heavy track with live performances incorporating visual elements taken from the government information film.

In print, Raymond Briggs' graphic novel When the Wind Blows (later adapted as an animated film, radio and stage play) obliquely mentions various aspects of the Protect and Survive programme. Louise Lawrence's children's novel Children of the Dust refers to one of the inner refuge designs mentioned in the leaflets and to the public information films and radio tapes.

On television, Protect and Survive was lampooned in the television series The Young Ones episode "Bomb." The "incredibly helpful and informative" pamphlet appears on-screen during the episode as characters hide ineffectively under clothed tables and paint themselves white to deflect the blast, parodying its instructions on creating an inner refuge and whitewashing one's windows, respectively.[13] The BBC television film Threads featured four of the series' films: Stay at Home, Make Your Fall-out Room and Refuge Now, Action After Warnings and Casualties. Also, in the Spooks episode "Nuclear Strike", the character Malcolm is seen viewing one of the information videos.

The full version of Protect and Survive is shown on a loop underground at the Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker[61] in Cheshire and the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker[62] in Essex. Other copies are shown on loops at the Imperial War Museums in London and Manchester. Fallout: London, a highly-publicized mod for the video game Fallout 4, includes multiple references to the Protect and Survive material, including a themed overhaul of the Pip-Boy featuring similar animations in lieu of Vault Boy.

Remove ads

See also

- Transition to war

- Preparing for Emergencies, a 2004 emergency preparedness campaign that also saw the British government prepare an information booklet for mass distribution

- Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

- Survival Under Atomic Attack, a 1951 US Government publication on nuclear survival

- Fallout Protection, a 1961 US Government publication on nuclear survival

- Duck and Cover (film)

- The War Game (film)

- Threads (film)

- List of books about nuclear issues

- List of films about nuclear issues

- Protect and Survive (Doctor Who audio drama)

- In case of crisis or war

- Sheltered (video game)

Remove ads

References

Footnotes

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads