Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

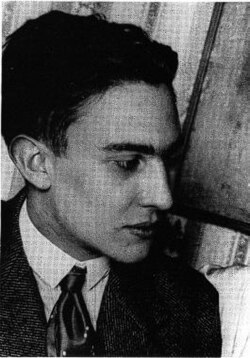

Raymond Radiguet

French novelist and poet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Raymond Radiguet (French: [ʁɛmɔ̃ ʁadiɡɛ]; 18 June 1903 – 12 December 1923) was a French novelist and poet. His two novels, noted for their explicit themes and unique style and tone, were praised by many of the greatest writers of the time.[1] He died unexpectedly at the age of twenty.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Raymond Maurice Radiguet was born in Saint-Maur, Val-de-Marne, close to Paris, the eldest of the seven children of Maurice Radiguet (1866-1941), a successful caricaturist, and Marie Radiguet (née Tournier, 1884-1958), who taught at a boarding school. When asked for news of his mother, Raymond would reportedly say: "I don't know. I never see her face. It's always lowered, as she ties the shoes of one of my brothers or sisters."[2] His father was a much more significant presence in his life, and Maurice Radiguet's mixture of permissiveness and near-rivalry with his eldest son heavily influenced the paternal dynamic in Le Diable au corps.[3]

On his mother's side, his family hailed from Martinique; his maternal grandfather had died in a shipwreck off the coast of Havana. The French West Indies were a lifelong fascination for Raymond (see the character of Mahaut in Le Bal du comte d'Orgel), and it has been suggested that his mother's fear of water, stemming from her father's death, was at the origin of Radiguet's poetic preoccupation with the beach. Cocteau claimed that Marie Radiguet's extraction explained the temperament of her son, who "sleeps during the day, smokes and loves sugar."[4]

Radiguet's earliest memory, as he recounted it later in Île de France, Île d'Amour, was of precocious sexuality: "I see myself, two years old, led by my nurse each morning to the girls' boarding school where my mother had graduated four years earlier. This gentle warmth of knees and breasts, I have never been able to recover it since, as I experienced it at the moment when I felt these caresses, so different from those of my mother or my nurse."[5]

In the same work, he sets down two childhood memories of death. In one, also drawn on at the beginning of Le diable au corps, a neighbor's maid commits suicide by throwing herself from a rooftop. In the other, a moment of erotic fascination gives way to horror as, watching a young couple on a swing, he sees the woman fall and break her neck: "Image worthy of a Greek tragedy."[5]

In 1917, he moved to the city. Soon he would drop out of the Lycée Charlemagne, where he studied, in order to pursue his interests in journalism and literature.[6]

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Radiguet found his first literary connection in André Salmon, editor of L'Intransigeant, to whom he brought several caricatures signed "Rajky." Some of his biographers have concluded, from his poor grades in art and the crudeness of his surviving drawings, that these caricatures were his father's work.[7] Salmon helped him find work at several newspapers; years later, recalling his impressions on first reading Radiguet's poetry, he wrote: "No question of a new Rimbaud. All the same, standing before one, a boy of fifteen already endowed with an indisputable poetic conscience..."[8]

His first published poem, again under the pseudonym of "Raimon Rajky," was "Aiguilles des secondes," which appeared in the September 1918 edition of L'Instant; his first publication under his real name was "Ligne d'horizon," which appeared two months later; and in December, he published a short story, "Tohu,"[9] in the avant-garde journal SIC. In February 1919, he met Max Jacob, with whom he became close at this time.

As one of the few writers in the immediate postwar milieu who had been too young to fight, Radiguet found himself an outsider in the generational struggle between modernists who were firmly established prior to the war––Jacob and Salmon, along with SIC and its editor Pierre Albert-Birot, were among these––and the younger generation, most of whom had fought in the war and many of whom were still mobilized. This younger generation found a voice in Pierre Reverdy's magazine Nord-Sud, and then in Dada. Radiguet made an attempt to ingratiate himself with this new avant-garde without alienating his older connections. This was partly successful (Radiguet is hailed as "a Parisian friend of Dada" in a poem by Tristan Tzara), but social miscalculations and a poor impression on Louis Aragon damaged these inroads.[7]

Radiguet's relationship with Jean Cocteau began in 1919. Despite Cocteau's characteristically dramatic account of their first meeting,[10] it is uncertain at which literary soirée they actually made first contact. On Radiguet's first being introduced at Cocteau's home, the butler announced him this way: "Sir, it's a child with a cane."[7] The nature of their relationship has been the cause of much speculation. Cocteau was famously homosexual, and Radiguet was only the most significant in a series of eroticized mentor-mentee relationships in Cocteau's life. However, it is uncertain whether the two were ever romantically or sexually involved.

In early 1923, Radiguet published his first and most famous novel, Le Diable au corps (The Devil in the Flesh). Its scandalous content, along with its autobiographical rapports, set off a literary cause célèbre. The novel tells the story of a young married woman who has an affair with an adolescent boy while her husband is away fighting at the front. Its plot, along with its cynical treatment of the war as "four years of summer vacation,"[11] tapped into an unacknowledged but profound national anxiety over the fidelity of soldiers' wives, some of whom had staved off loneliness through affairs with older men or adolescent boys.[12] According to Radiguet family friend Yves Krier, it was Maurice Radiguet that Alice Serrier (née Saunier), on whom the character of Marthe was based, initially intended to seduce.[13] Alice Serrier's husband, Gaston Serrier, was a soldier at the front. The scandal followed the couple for decades, and the paternity of their child was called into question by the press; Gaston always maintained his wife's innocence.[12]

During the last months of his life, Radiguet was engaged to model Bronia Perlmutter (1906-2004), who later married filmmaker René Clair. An anecdote told by Ernest Hemingway has an enraged Cocteau charging Radiguet (known in the Parisian literary circles as "Monsieur Bébé" – Mister Baby) with decadence for this behavior: "Bébé est vicieuse. Il aime les femmes." ("Baby is depraved. He likes women." [Note the use of the feminine adjective.]) Radiguet, Hemingway implied, employed his sexuality to advance his career: being a writer "who knew how to make his career not only with his pen but with his pencil."[14][15]

Radiguet's second novel, Le bal du Comte d'Orgel (Count d'Orgel's Ball), also dealing with adultery, was only published posthumously in 1924, and also proved controversial.

In addition to his two novels, Radiguet's works include a few poetry volumes and a play.[6]

Legacy

In 1945, Stead and Blake wrote that admirers of his first novel "include the most discriminating of critics."[16] Aldous Huxley is quoted as declaring that Radiguet had attained the literary control that others required a long career to reach. François Mauriac said that Le Diable au corps is "unretouched and seems shocking, but nothing so resembles cynicism as clairvoyance. No adolescent before Radiguet has delivered to us the secret of that age: we have all falsified it."[16] In his commentary on the Hagakure, Japanese writer Yukio Mishima writes that Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel was "the book that thrilled me most" as a child, and that Radiguet became a sort of adolescent rival for him, as he expected to die equally early in World War II.[17] Radiguet is the last entry in André Gide's Anthologie de la Poèsie Française; Gide selects for inclusion "Amélie" from Devoirs de Vacances and "Avec la mort tu te maries..." from Les Joues en feu.[18]

Numerous portraits of Radiguet, by artists such as Pablo Picasso,[19] Amedeo Modigliani, Man Ray,[20] and Valentine Hugo, as well as many drawings of him by Jean Cocteau,[21] were produced during his lifetime.

Remove ads

Death

Summarize

Perspective

On 12 December 1923, Radiguet died at age 20 in Paris of typhoid fever, which he contracted after a trip he took with Cocteau. According to his friend Jean Hugo, Radiguet "had fallen ill at the hôtel Foyot, rue de Tournon, where he had a room above the celebrated restaurant. A charlatan, Dr. C., in whom Cocteau placed a blind confidence, did not know how to spot the symptoms of typhoid fever. The state of the patient worsened and when they transported him at last to a clinic, rue Piccini, it was too late."[22] It has been suggested that Cocteau's jealousy over Radiguet's engagement caused him to neglect his care.

Cocteau, in an interview with The Paris Review, stated that Radiguet had told him three days before his death that, "In three days, I am going to be shot by the soldiers of God."[23] In reaction to this death Francis Poulenc wrote, "For two days I was unable to do anything, I was so stunned".[24] Several other friends of Radiguet's reported strange premonitions prior to his death. Hugo writes that during a séance, a spirit giving its name as "Beauharnais" (Radiguet traced his ancestry back to a relative of Joséphine de Beauharnais[4]) had Radiguet dismissed from the room, then told the others gathered: "I want his youth."[22] Bernard Grasset wrote that at their last meeting, Radiguet gave him his scarf as a keepsake.[25]

In her 1932 memoir, Laughing Torso, British artist Nina Hamnett describes Radiguet's funeral: "The church was crowded with people. In the pew in front of us was the negro band from Le Boeuf sur le Toit. Picasso was there, Brâncuși and so many celebrated people that I cannot remember their names. Radiguet's death was a terrible shock to everyone. Coco Chanel, the celebrated dressmaker, arranged the funeral. It was most wonderfully done."[26]

Radiguet left behind plans for a novel based on the life of the poet Charles d'Orléans.[25] A volume of erotic verse, Vers libres, was published posthumously; the fact of Radiguet's authorship was not acknowledged by his family for many years.

Remove ads

Bibliography

- Les Joues en feu (1920) – poetry, translated by Alan Stone as Cheeks on Fire: Collected Poems

- Devoirs de vacances (1921) – poetry (English translation Holiday Homework)

- Les Pelican (1921) – drama, translated by Michael Benedikt and George Wellworth as The Pelicans

- Le Diable au corps (1923) – novel, translated by Kay Boyle as The Devil in the Flesh

- Le Bal du comte d'Orgel (1924) – novel, translated by Malcolm Cowley as The Count's Ball

- Oeuvres completes (1952) – translated as Complete Works

- Regle du jeu (1957) – translated as Game Rule

- Vers Libres & Jeux Innocents, Le Livre a Venir (1988)

Remove ads

Film adaptations

In 1947, Claude Autant-Lara released his film Le diable au corps, based on Radiguet's novel, and starring Gérard Philipe. Coming just after World War II, the movie caused controversy in its turn. Among the other cinematic versions of Radiguet's story, the heavily adapted version by Marco Bellocchio, Il diavolo in corpo (1986), was notable as being among the first mainstream films to show unsimulated sex.[27]

In 1970, Le Bal du comte d'Orgel was adapted into a film, starring Jean-Claude Brialy as Le comte Anne d'Orgel. It was the last movie directed by Marc Allégret, who, like Radiguet, had once fallen under the spell of Cocteau.

In 2000, Radiguet's life and work were examined by Jean-Christophe Averty in Les deux vies du chat Radiguet, for the TV series Un siècle d'écrivains.[28]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads