Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Renaud Camus

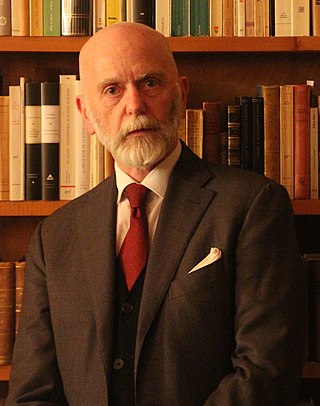

French novelist and conspiracy theorist (born 1946) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Jean Renaud Gabriel Camus (/kæˈmuː/; French: [ʁəno kamy]; born 10 August 1946) is a French novelist and conspiracy theorist. He is the originator of the far-right "Great Replacement" conspiracy theory, which claims that a "global elite" is colluding against the white population of Europe to replace them with non-European peoples.[2][3]

Camus's writings on the "Great Replacement" have been translated on far-right websites and used to promote the white genocide conspiracy theory.[4] Camus has repeatedly condemned and publicly disavowed violent acts which have been perpetrated by far-right terrorists inspired by his theories.[5][6][7][8]

Remove ads

Early life and career as a fiction writer

Summarize

Perspective

Family and education (1946–1977)

Jean Renaud Gabriel Camus[9] was born on 10 August 1946[10] in Chamalières, Auvergne, a rural town in central France.[11][12] Raised in a bourgeois family,[13] he is the son of Léon Camus, an entrepreneur, and Catherine Gourdiat, a lawyer.[14] His parents removed him from their will after he revealed his homosexuality. At 21, then a socialist, he participated in pro-LGBT marches during the May 1968 events in Paris.[12]

Camus earned a baccalauréat in philosophy in Clermont-Ferrand, Auvergne, in 1963. He then spent a year at a non-university college, St Clare's, Oxford (1965–1966). He earned a bachelor in French literature at the University of Paris (1969), a master in philosophy at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (1970),[15][16] and two Masters of Advanced Studies (DES) in political science (1970) and history of law (1971) at the University Panthéon-Assas. He taught French literature at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas from 1971 to 1972, then was a redactor in political science for the encyclopaedia-publisher Grolier from 1972 to 1976. He was also a professional reader and literature advisor at the French book-publisher Denoël from 1970 to 1976.[15]

Influential gay writer (1978–1995)

After settling back in Paris in 1978, Camus quickly began to circulate among writers and artists the likes of Roland Barthes, Andy Warhol and Gilbert & George.[13] Known exclusively as a novelist and poet until the late 1990s, Camus received the Prix Fénéon in 1977 for his novel Échange,[17] and in 1996 the Prix Amic from the Académie Française for his previous novels and elegies.[18][19]

Called retrospectively by some English-language media an "edgy gay writer",[13][19] Camus published Tricks in 1979, a "chronicle" consisting of descriptions of homosexual encounters in France and elsewhere, with a preface by the philosopher Roland Barthes; it remains Camus's most translated work.[20] Tricks and Buena Vista Park, published in 1980, were deemed influential in the LGBT community at that time.[21][22][19] Camus was also a columnist for the French gay magazine Gai pied.[22][13] This period of Camus's life has led the American magazine The Nation to label him a "gay icon" who "became the ideologue of white supremacy",[19] although Camus had rejected the concept of "homosexual writer" by 1982.[23]

Camus was a member of the Socialist Party during the 1970s and 1980s, and he voted for François Mitterrand in 1981, winner of the French presidential election.[12] Thirty-one years later, during the 2012 presidential campaign, he dismissed the party with the following remark: "The Socialist Party has published a political program titled Pour changer de civilisation ("To change civilization"). We are among those who, to the contrary, refuse to change civilization."[24]

In 1992, at the age of 46, using the money from the sale of his Paris apartment, Camus bought and began to restore a 14th-century castle in Plieux, a village in Occitanie. In 1996, he had the epiphany which he said led to the concept of the "Great Replacement".[13] As of 2019, Camus still lives in the castle. Because he received government funding to assist in the restoration of the castle – which included the rebuilding of a 10-story tower removed in the 17th century – Camus is required to open it to the public for a part of the year.[20][19]

Remove ads

Great Replacement

Summarize

Perspective

Development (1996–2011)

Camus stated in an interview in 2016 with the British magazine The Spectator that he began to develop his idea in 1996 while editing a guidebook about the department of Hérault. He claimed that he "suddenly realised that in very old villages ... the population had totally changed" and added, "this is when I began to write like that."[13]

Camus supported for a time the left-wing souverainist politician Jean-Pierre Chevènement, then voted for the ecologist candidate Noël Mamère in the 2002 presidential election.[12] The same year, he founded his own racialist political party,[25] the Parti de l'In-nocence ("Party of No-harm"), although it was not publicly launched until the 2012 presidential election.[13] The party advocates remigration, i.e. sending all immigrants and their families back to the country of their origin, and a complete cessation of future immigration.[20]

He also declared that a key to understanding his "Great Replacement" theory can be found in a book about aesthetics he published in 2002, titled Du Sens ("Of Meaning").[13] In the latter, inspired by a dialogue between Plato and Cratylus, he wrote that the words "France" and "French" equal a natural and physical reality, not a legal one; it is a form of Cratylism similar to Charles Maurras's distinction between the "legal country" and the "real country."[a][26] Camus also built on the earlier work of Jean Raspail, who published the dystopian novel The Camp of the Saints in 1973, about immigration and the destruction of Western civilisation.[27]

Political activism (2012–present)

He was a candidate in the 2012 French presidential election, with a programme ranging from "serious proposals, such as the repatriation of foreign-born criminals", to unusual themes in French politics, such as "the right to silence, abolishing wind-farms, banning roadside ads, making sanctuaries of remaining unspoiled places, stopping the production of cars that can go faster than the speed limit, and recognising Israel, Palestine and a Greater Lebanon for Christians in the Middle East."[13] He failed to gain enough elected representatives presentations to be able to run for president, and eventually decided to support Marine Le Pen.[24][28]

In 2015, Camus headed an initiative to launch Pegida France alongside Pierre Cassen of Riposte Laïque, Jean-Luc Addor of the Swiss People's Party, Pierre Renversez of the Belgian "No to Islam" and Melanie Dittmer of the German Pegida.[29][30]

In December 2017, he declared: "The presidential election that took place [in 2017] was the last chance for a political solution. I don't believe in a political solution ... because in 2022, this time, it will be the occupants, the invaders [i.e. the immigrants] who will vote, who will be the masters of the elections, so anyway the solution is no longer political".[25]

In May 2019, Camus ran, along with Karim Ouchikh, for the European parliament elections: "we shall not leave Europe, we shall make Africa leave Europe," they wrote to define their agenda.[31][32] During the campaign, a photograph of a candidate on his ballot kneeling before a giant swastika drawn on a beach re-emerged on social media. Camus decided to withdraw from the election, claiming that the swastika was "the opposite of everything [he had] fought for [his] whole life."[19][33] During the 2022 French presidential election, he sided with the far-right pundit and presidential candidate Éric Zemmour.[34]

In April 2025, Camus had his ETA for entry into the United Kingdom withdrawn, with the British Home Office stating that his "presence in the UK is not conducive to the public good." This decision was not appealable.[35] This was as Camus planned to visit the Homeland Party's "Big Remigration Conference", which was scheduled to take place on 26 April 2025, and then to speak at the Oxford Union within the same month.[36]

Remove ads

Views

Summarize

Perspective

Great Replacement

Since his 2010 and 2011 books L'Abécédaire de l'in-nocence ("Abecedarium of no-harm") and Le Grand Remplacement ("The Great Replacement")—both unpublished in English—Camus has been warning of the purported danger of the "Great Replacement".[37] The conspiracy theory supposes that "replacist elites"[b] are colluding against the White French and Europeans in order to replace them with non-European peoples—specifically Muslim populations from Africa and the Middle East—through mass immigration, demographic growth and a drop in the European birth rate; a supposed process he labelled "genocide by substitution."[2][38] To promote his theory, Camus participated in two conferences organised by Bloc Identitaire in December 2010 and November 2012.[25]

On 9 November 2017, Camus founded, with Karim Ouchikh, the National Council of European Resistance, an allusion to the WWII French National Council of the Resistance.[39] The pan-European movement—with other members the likes of Jean-Yves Le Gallou, Bernard Lugan, Václav Klaus, Filip Dewinter or Janice Atkinson[40]—seeks to oppose the "Great Replacement", immigration to Europe, and to defeat "replacist totalitarianism".[41][42] In 2017 the French essayist Alain Finkielkraut caused controversy after he invited Camus to debate the "Great Replacement" on the literary talk show Répliques at the public radio France Culture. Finkielkraut justified his choice by arguing that Camus, who "is heard and seen nowhere, has shaped an expression that we hear everywhere."[6][43] After white supremacist protesters at the 2017 Unite The Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, were heard chanting "You will not replace us" and "Jews will not replace us,"[44] Camus stated that he did not support Nazis or violence, but that he could understand why white Americans felt angry about being replaced, and that he approved of the sentiment.[45] In November 2018 he published a book directly written in English and intended for an international audience, titled You Will Not Replace Us![46]

As of February 2023, he continued to defend the "Great Replacement" conspiracy theory on his Twitter account,[47] which had around 54,000 followers at the time of its permanent suspension in October 2021.[48] Camus's account was reactivated in January 2023 thanks to a policy of general amnesty announced by Twitter's new owner, Elon Musk.[49]

White nationalist violence

Camus has repeatedly said that he condemns the violent attacks and terrorism committed in echo with his ideas,[5][6][7][8] dismissing them as "Occupier's practices."[50] While he denies stigmatising all Muslims, Camus believes in an unbroken line between petty crime and Islamic terrorism: "all the terrorists are known by the police, not for terrorist acts or for religious extremism, but by petty larceny and bank attacks, or even by very small things like attacking old ladies in suburban trains, or conflicts between neighbours",[13] adding in another speech: "we are talking about the fight against terrorism: in my opinion there are no terrorists, not a single one. There are occupants who ... kill a few hostages from time to time to better remind us who the master is."[25]

I therefore believe that we are entering into an absolute necessity of a struggle that will no longer be political ... for which there are two main sources of inspiration: that of the Resistance and that of anti-colonial struggles. We are under occupation—I am absolutely not afraid of the word, I often speak of the second occupation ... We also follow the tradition of all anti-colonial struggles ... Algeria, which has become independent, has considered that it would not be truly independent without the departure of the settlers ... I also believe that there will be no liberation of the territory without the departure of the occupier or colonization, i. e. without remigration. All the major texts in the fight against decolonization apply admirably to France, in particular those of Frantz Fanon ... Faced with this, I propose open resistance, that is, to revolt.

— Renaud Camus. Speech of the 10 years of Riposte Laïque, 2 December 2017.

The scholars Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, and Ahmed Boubeker state that "the announcement of a civil war is implicit in the theory of the 'great replacement' ... This thesis is extreme—and so simplistic that it can be understood by anyone—because it validates a racial definition of the nation."[51] In April 2014 Camus was fined €4,000 for incitement to racial hatred after he referred to Muslims as "hooligans" and "soldiers" and as "the armed wing of a group intent on conquering French territory and expelling the existing population from certain areas" during a conference organised by Bloc Identitaire and Riposte Laïque in December 2010.[52][13] In April 2015 the Court of Appeal of Paris confirmed this decision.[53]

Allegations of antisemitism

In his diary of 1994—published in 2000 under the title La campagne de France—Camus commented on the fact that the membership of a regular panel of literary critics on the public radio station France Culture comprised a majority of Jewish members who, in his view, tended to discuss mostly Jewish authors and Jewish-related issues.[54][19] This accusation drew much criticism among some French journalists such as Marc Weitzmann or Jean Daniel, who denounced Camus's remarks as antisemitic.[55][19] One editorial, signed by Frédéric Mitterrand, Emmanuel Carrère, Christian Combaz and Camille Laurens, defended Camus in the name of free speech, while another, signed by Jacques Derrida, Serge Klarsfeld, Claude Lanzmann, Jean-Pierre Vernant and Philippe Sollers, contended that racism and antisemitism, as allegedly displayed by Camus in his diary, are not entitled to this freedom.[55]

Camus has since gained a number of defenders among French-Jewish conservative thinkers, most notably Alain Finkielkraut, who has taken his side in the controversy since 2000. "Demographic substitution", Finkielkraut said to The Nation in 2019, is "not a conspiracy theory", but he dismissed Camus's frequent talk of "genocide by substitution".[19] Éric Zemmour, a French conservative journalist of Sephardic Jewish descent, is one of the most prominent mainstream advocates of Camus's theory.[43][56] Additionally, various right-wing and far-right French-speaking Jewish websites, such as Dreuz.info, Europe-Israël or JssNews, have positively received Camus's conspiracy theory and have called their readership to study his books.[57]

The political scientist Jean-Yves Camus and the historian Nicolas Lebourg have noted that, contrary to its parent the white genocide conspiracy theory, Camus's "Great Replacement" does not include an antisemitic Jewish plot, which is, according to them, a reason for its success.[58] The French journalist Yann Moix, who had accused Camus of being an antisemite in 2017, was fined €3,000 by a French Court of Appeal for libel on 13 March 2019.[59] Moix's conviction was overturned in January 2020 by the French Court of Cassation, judging that his comments "were the expression of an opinion and a value judgment on the personality of the plaintiff ... and not the imputation of a specific fact."[60]

Democracy and multiculturalism

Camus sees democracy as a degradation of high culture and favours a system whereby the elite are guardians of the culture, thus opposing multiculturalism.[26]

LGBT rights

Camus, who is gay, has given support to same-sex marriage.[22] He has said that homophobia and opposition to gay rights within conservative Islam justifies anti-Muslim sentiment, and that the mainstream left has often prioritised defending Islam and anti-racism over criticising Muslim homophobia.[26]

Remove ads

Influence

Summarize

Perspective

In a survey led by Ifop in December 2018, 25 per cent of the French subscribed to the theory of the "Great Replacement"; as well as 46 per cent of the responders who defined themselves as "Gilets Jaunes".[61] In another survey led by Harris Interactive in October 2021, 61 per cent of the French believed that the "Great Replacement" will happen in France; 67 per cent of the respondents were worried about it.[62] The theory has been cited by the Canadian political activist Lauren Southern in a YouTube video of the same name released in July 2017.[63] Southern's video had attracted in 2019 more than 670,000 viewers[64] and is credited with helping to popularize the theory.[65]

The "Great Replacement" theory is a key ideological component of Identitarianism, a strand of white nationalism that originated in France and has since gained popularity in Europe and the rest of the Western world.[66]

Although Camus has repeatedly condemned and publicly disavowed violent acts perpetrated by far-right terrorists,[5][6][7][8] several far-right terrorists, including the perpetrators of the shootings in Christchurch (2019), El Paso (2019), and Buffalo (2022), have made reference to the "Great Replacement" conspiracy theory. The "Great Replacement" was used as the name of a manifesto by the terrorist Brenton Tarrant, perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings that killed 51 Muslims and injured 40 others. Likewise, Tarrant's manifesto and the Great Replacement theory were also cited in The Inconvenient Truth by Patrick Crusius, the perpetrator of the shooting at a Walmart store in El Paso, Texas, that killed 23 Latinos and injured 23 others.[67][68] Payton Gendron, who perpetrated the Buffalo shooting at a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York, which killed ten people, all of whom were black, described himself as a white supremacist and voiced support for the Great Replacement conspiracy theory of Camus in his manifesto.[69][70][71] About 28 per cent of the document was plagiarised from other sources, especially Tarrant's manifesto.[72][73]

Camus has condemned the Christchurch massacre and described the shootings as a terrorist attack, adding that Tarrant's manifesto had failed to understand the Great Replacement theory. Camus said that he suspected the attacks to be inspired by acts of Islamic terrorism in France.[74] In a discussion with The Washington Post, he said that while he was against the use of violence, he still supported a sort of "counter-revolt" against non-White immigration and had no issues with the majority of his supporters' beliefs.[75] The scholar Jean-Yves Camus sees Tarrant's ideas as more extreme than Camus' replacement theory, and argues that they are more firmly rooted in Jean Raspail's thinking.[7]

According to scholars, Camus' Great Replacement theory can only lead to acts of violence, by presenting non-whites as an existential threat to white people,[76][77] and immigrants as a fifth column or an "internal enemy".[78] Camus' use of strong terms like "colonisation" and "Occupiers" to label non-European immigrants and their children (in analogy to the Nazi occupation of France),[79][80] has been described by the philosopher Alain Finkielkraut as implicit calls to violence.[81]

Remove ads

See also

Selected works

Summarize

Perspective

Novels

- Passage. Flammarion (1975) ISBN 978-2080607829

- Échange. Flammarion (1976) ISBN 978-2080608925

- Roman roi. P.O.L. (1983) ISBN 978-2867440052

- Roman furieux (Roman roi II). P.O.L. (1987) ISBN 978-2867440762

- Voyageur en automne. P.O.L. (1992) ISBN 978-2867443022

- Le Chasseur de lumières. P.O.L. (1993) ISBN 978-2867443725

- L'épuisant désir de ces choses. P.O.L. (1995) ISBN 978-2867444494

- L'Inauguration de la salle des Vents. Fayard (2003) ISBN 978-2213616643

- Loin. P.O.L. (2009) ISBN 978-2846823524

Chronicles

- Journal d'un voyage en France. Hachette (1981) ISBN 978-2010067815

- Tricks. P.O.L. (1979) ISBN 978-2818001387

- transl. Tricks: 25 encounters. Serpent's Tail (1995) ISBN 978-1852424145

- Buena Vista Park. Hachette (1980) ISBN 978-2010073052

- Incomparable, with Farid Tali. P.O.L. (1999) ISBN 978-2867447044

- Retour à Canossa. Journal 1999. Fayard (2002) ISBN 978-2213614342

Political writings

- Du sens. P.O.L. (2002) ISBN 978-2867448812

- Le communisme du XXIe siècle. Xenia (2007) ISBN 978-2888920342

- La Grande Déculturation. Fayard (2008) ISBN 979-1091681384

- De l'In-nocence. Abécédaire. David Reinharc (2010) ISBN 978-2-35869-015-7

- Décivilisation. Fayard (2011) ISBN 2-2136-6638-5

- Le Grand Remplacement. David Reinharc (2011) ISBN 978-2-35869-031-7

- L'Homme remplaçable. Self-published (2012) ISBN 979-10-91681-00-1

- Le Changement de peuple. Self-published (2013) ISBN 979-10-91681-06-3

- Les Inhéritiers. Self-published (2013) ISBN 979-10-91681-04-9

- You Will Not Replace Us! Self-published (2018) ISBN 979-1091681575

- Lettre aux Européens : entée de cent une propositions (with Karim Ouchikh). Self-published (2019)

- Le Petit Remplacement. Pierre-Guillaume de Roux (2019) ISBN 978-2491446758

- La Dépossession : ou Du remplacisme global. La Nouvelle Librairie (2022) ISBN 978-2493898289

- Enemy of the Disaster: Selected Political Writings of Renaud Camus, edited with an introduction by Louis Betty. Vauban Books (2023) ISBN 979-8988739906

- The Deep Murmur: Preceded by Elegy for Enoch Powell. Vauban Books (2024) ISBN 979-8988739913

Remove ads

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads