Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

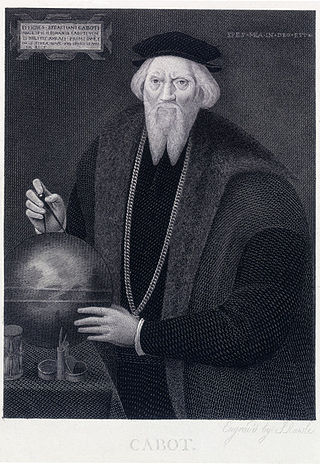

Sebastian Cabot (explorer)

Venetian explorer (c. 1474 – c.1557) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sebastian Cabot (Italian and Venetian: Sebastiano Caboto, Italian: [sebaˈstjaːno kaˈbɔːto]; Spanish: Sebastián Caboto, Gaboto or Cabot; c. 1474 – c. December 1557) was a Venetian explorer, who at various times was in the service of the Kingdom of England, the Crown of Aragon and the Holy Roman Emperor. Cabot was likely born in the Venetian Republic and as such may have been a Venetian citizen, however this has never been confirmed. Cabot himself gave varying accounts of his national origins to different audiences, such as claiming to have been born in Bristol, England. He was the son of Venetian explorer John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) and his Venetian wife Mattea and he grew up in England during his youth.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

After his father's death, Cabot conducted his own voyages of discovery, charting the Eastern American seaboard and seeking the Northwest Passage on behalf of England. He later sailed for Spain, traveling to South America, where he explored the Rio de la Plata and established two new forts.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Summarize

Perspective

Accounts differ as to Sebastian Cabot's place and date of birth. The historian James Williamson reviewed the evidence for various given dates in the 1480s and concluded that Sebastian was born not later than 1484, the son of John Cabot, a Venetian citizen credited with Genoese or Gaetan origins by birth, and of Mattea Caboto, also Venetian.[1] Late in life, Cabot himself told Englishman Richard Eden that he was born in Bristol, and that he travelled back to Venice with his parents at four years of age, returning again with his father, so that he was thought to be Venetian.[2] At another time, he told the Venetian ambassador at the court of Charles V, Gasparo Contarini (who noted it in his diary), that he was Venetian, educated in England.[1] In 1515 Sebastian's friend Peter Martyr d'Anghiera wrote that Cabot was a Venetian by birth, but that his father (John Cabot) had taken him to England as a child.[1] His father had lived in Venice from 1461, as he received citizenship (which required 15 years' residency) in 1476. The Caboto family moved to England in 1495 if not before.

Sebastian, his elder brother Ludovico and his younger brother Santo were included by name with their father in the royal letters patent from King Henry VII of March 1496 authorizing their father's expeditions across the Atlantic.[3] They are believed by some historians, including Rodney Skelton, still to have been minors since they were not mentioned in the 1498 patent their father also received.[4] John Cabot sailed from Bristol on the small ship Matthew and reached the coast of a "New Found Land" on 24 June 1497. Historians have differed as to where Cabot landed, but two likely locations often suggested are Newfoundland and Nova Scotia.

1494 Cabot scouting expedition

According to Cartografía Marítima Hispana,[5] Sebastian Cabot included a handwritten text in Latin on his famous map of North America (published in Antwerp, 1544) claiming to have discovered North America with his father in 1494, three years before his father's voyage.[6] Sancho Gutierrez repeated this text in Castilian on his 1551 map.[7][8]

Placed next to the border of North America, the text reads:

This land was discovered by Johannes Caboto, venetian and Sebastian Caboto, his son, in the year of the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ MCCCCXCIV, 24th of June in the morning. They put to it the name 'prima terra vista' and [...] This big island was named Saint John, as it was discovered on Saint John holiday. People there wander wearing animal furs. They use bow and arrow to fight, javelins and darts and wooden batons and slings. This is a very sterile land, there are a lot of white bears and very big deers, big as horses, and many other animals. As well there are infinite fish: plaices, salmons, very long soles, 1 yard long and many other varieties of fish. Most of them are called cod. And there are also black hawks, black as ravens, eagles, partridges and many other birds.

The year is stated as MCCCCXCIV (1494) in both hand-written versions. There cannot be confusion with the commonly accepted date for the Cabots' voyage, in 1497. Two suppositions can explain this. Sebastian Cabot and Sancho Gutiérrez may have changed the date in the middle of the sixteenth century. Intentional changes and inaccuracies were very common among geographers at the time, depending on the political interests of their sponsors. As Cabot was funded at the time of the map by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, he may have been interested in showing that the first travel to North America was in 1494 and thus funded by Castilians or by Portuguese, and not by English or French. By the time Cabot was sponsored by Germany and Spain, both England and France had started claiming shares of the New World in competition with Spain and Portugal.[citation needed]

If Cabot and Gutiérrez stated the correct year, it would mean the Cabots sailed to North America on their own account, before proposing their services to England in 1496. No contemporaneous documentation for this has survived.

Remove ads

Early career with England and Spain

Summarize

Perspective

In 1504 Sebastian Cabot led an expedition from Bristol to the New World, using two ships: Jesus of Bristol and Gabriel of Bristol. These were mastered by Richard Savery and Philip Ketyner, respectively, and fitted out by Robert Thorne and Hugh Elyot. They brought back a certain amount of salted fish, which suggests the voyage was at least partly commercial and that other expeditions may also have included fishing. Cabot was granted an annuity of £10 on 3 April 1505 by Henry VII for services "in and aboute the fyndynge of the new founde landes".[9]

In 1508–09 Cabot led one of the first expeditions to find a North-West passage through North America. He is generally credited with gaining "the high latitudes", where he told of encountering fields of icebergs and reported an open passage of water, but was forced to turn back. Some later descriptions suggest that he may have reached as far as the entrance of Hudson Bay. According to Peter Martyr's 1516 account Sebastian then sailed south along the east coast of North America, passing the rich fisheries off the coast of Newfoundland, going on until he was "almost in the latitude of Gibraltar" and "almost the longitude of Cuba". This would imply that he reached as far as the Chesapeake Bay, near what is now Washington, D.C.[10] Returning home "he found the King dead, and his son cared little for such an enterprise".[11] This suggests Sebastian arrived back in England shortly after the death of Henry VII in April 1509 and the accession of Henry VIII, who did indeed show much less interest in the exploration of the New World than his father.

By 1512 Cabot was employed by Henry VIII as a cartographer, supplying the king with a map of Gascony and Guienne.[12] In the same year he accompanied the Marquess of Dorset's expedition to Spain, where he was made captain by Ferdinand V. Cabot believed that Spain was more interested in major exploration, but his hopes of getting Ferdinand's support were lost with the king's death. In the turmoil afterward, no plans would be made for new expeditions, and Cabot returned to England.

The scholar and translator/civil servant Richard Eden, who came to know Cabot towards the end of his life, ascribed to the explorer 'the governance' of a voyage of c.1516 under English flag.[13] This has been accepted and elaborated by a number of English writers, particularly of the turn of the nineteenth century.[14][15] Rodney Skelton, author of Cabot's entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography,[4] connected Eden's text to a known expedition of 1517 which indeed aborted, but is not known to have involved Cabot;[16] while the historian Alwyn Ruddock transferred Eden's story of the opposition to Cabot's plans of Thomas Spert, future master of the king's ship Mary Rose, to the explorer's voyage of 1508–9.[9]

Cabot's effort's in 1521 to bring together and lead an English discovery voyage to North America are well attested. He had the support of Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey, and some offers of backing in money and ships from both Bristol and London merchants. But the Drapers Company expressed their distrust of Sebastian, and offered only limited funds. The response of other livery companies is unknown. The project was abandoned, and Cabot returned to Spain.[17]

Remove ads

Service to Spain

Summarize

Perspective

In 1512, believing that King Ferdinand II of Aragon was offering more financial support for exploration than the English crown, Cabot moved from England to Spain.[18] King Ferdinand’s death in 1516 brought this period of Spanish exploration to a halt, prompting Cabot to return to England.

By 1522, Cabot was again in Spanish service, this time as a member of the Council of the Indies and holding the title of Pilot Major,[19] responsible for overseeing naval training and the instruction of navigators. Around this time, he secretly contacted the Council of Ten in Venice, offering to search for the Northwest Passage to China on Venice’s behalf if they would receive him.[15]

In March 1525, Cabot was commissioned as captain general of a Spanish fleet. His mission was to determine, through astronomical observations, the precise demarcation line of the Treaty of Tordesillas between Spanish and Portuguese territories. He was also tasked with transporting settlers to the Molucca Islands to strengthen Spanish claims in the Pacific. Officially, the voyage was described as an expedition to discover Tarshish, Ophir, Eastern Cathay, and Cipango (Japan). The fleet consisted of four ships and 250 men, departing Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 3 April 1526.

By then, survivors of Magellan’s expedition had completed the first circumnavigation, revealing the world to be larger than expected. This intensified pressure on Spain and Portugal to define their respective territories. Cabot was instructed to cross the Pacific twice, which might have resulted in a second circumnavigation. However, upon landing in Brazil, he heard reports of great wealth in the Incan king’s realm and the recent expedition of Aleixo Garcia. Abandoning his original orders, Cabot turned inland to explore the Río de la Plata along what is now northern Argentina.

Cabot’s leadership soon faced challenges. His crew became discontented after the fleet was stranded in the doldrums and the flagship ran aground off Santa Catarina Island. When Cabot diverted the mission to the Río de la Plata, opposition arose from Martin Méndez (his lieutenant general), Miguel de Rodas (pilot of the Capitana), and Francisco de Rojas (captain of another vessel). Cabot suppressed the mutiny by marooning the dissenters and several other officers on Santa Catarina Island, where they are believed to have died.

Cabot then explored the wide Río de la Plata estuary for five months, establishing San Salvador at the confluence of the Uruguay and Río San Salvador, the first Spanish settlement in present-day Uruguay. Leaving the two larger ships there, he sailed up the Paraná River in a brigantine and a galley built at Santa Catarina. At the junction of the Paraná and the Río Carcarañá, he built Espíritu Santo, the first Spanish settlement in modern-day Argentina. The nearby town of Gaboto was later named in his honour. After losing 18 men in an ambush, Cabot returned to San Salvador, passing Diego García’s expedition along the way.

Following this meeting, Cabot sent the Trinidad back to Spain on 8 July 1528 with his reports, accusations against the mutineers, and requests for aid.[20] In spring 1529, he returned upriver to Espíritu Santo, only to find it had been destroyed by Indigenous attackers during his absence. Recovering the cannon, he withdrew to San Salvador.

On 6 August 1529, a council decided to return to Spain. Cabot and García stopped at São Vicente, where Cabot purchased 50 slaves, then followed the Brazilian coast before crossing the Atlantic. He reached Seville on 22 July 1530 with one ship and 24 men.

Upon his return, Cabot faced charges from the Crown, from Rojas, and from the families of Rodas and Méndez. The Council of the Indies convicted him of disobedience, mismanagement, and causing the deaths of officers, sentencing him to heavy fines and two years’ exile in Oran, North Africa.[21]

During the proceedings, the Emperor was absent in Germany. On his return, Cabot presented descriptions of the region. Although no pardon was recorded and the fines were still paid, Cabot was never exiled. He retained the title of pilot-major until 1547 and eventually left Spain for England without losing his title or pension.

Remove ads

Later years

In the year 1553, Cabot discussed a voyage to China and re-joining the service of Charles V with Jean Scheyfve, the king's ambassador in England.[22] In the meantime Cabot had reopened negotiations with Venice, but he reached no agreement with that republic. After this he acted as an advisor for "English ventures for discovery of the Northwest Passage. He became governor of the Muscovy Company in 1553 and, along with John Dee,[23] helped it prepare for an expedition led by Sir Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancellor.[4] He was made life-governor of the "Company of Merchant Adventurers", and equipped the 1557 expedition of Steven Borough.[24] By February 1557, he was replaced as governor of the Muscovy Company. He was recorded as receiving a quarterly pension, which he was first paid in person. Someone picked up for him in June and September 1557, and no one was paid in December, suggesting that he had died by then.[4]

Remove ads

Marriages and family

Summarize

Perspective

Cabot married Joanna (later recorded as Juana in Spanish documents.) They had children before 1512, the year he entered Spanish service. That year, he returned to London to bring his wife and family to Seville. By 14 September 1514, his wife was dead. Among his children was a daughter Elizabeth. An unnamed daughter was recorded as dying in 1533.[4]

Catalina de Medrano

In Spain Sebastian Cabot married again, in 1523, to Catalina de Medrano, widow of the conquistador Pedro Barba.[25] It is not known if the marriage between Sebastian and Catalina produced offspring. But since the Spanish wills of both Catalina (1547) and Sebastian (1548) name nieces of Catalina as their heirs, it is unlikely that by the time of Catalina's death, the pair had children surviving from their marriage.[25] Catalina died on 2 Sep 1547.[4]

Various official documents, from 25 Aug. 1525, name Cabot's wife as Catalina de Medrano. Witnesses in the lawsuits following Cabot's return to Spain in 1530 testified that his wife was a domineering woman who handled his affairs. Catalina's daughter Catalina Barba y Medrano died in 1533. The reference to "sons" of Catalina de Medrano, found in one document only, of 1525, may be merely an official formalism.[26] On June 22, 1523, Sebastian Cabot, acting as Catalina Barba y Medrano's guardian, appointed Fernando de Jerez as her attorney and arranged her property schedule. While it’s unclear why Cabot became her guardian, it was likely appointed by her father, Pedro Barba, before his departure for Havana. Barba, a relative of Amerigo Vespucci, may have chosen Cabot due to respect for navigators. Cabot’s debt to Maria Cerezo escalated tensions over Barba’s estate, leading Cerezo to question Catalina Barba y Medrano’s legitimacy.[27]

In November 1523, a Real Cédula confirmed Catalina Barba y Medrano’s legitimacy and marriage, ending legal disputes. Cabot's financial struggles included unpaid pensions to Cerezo, partially resolved through deductions from his salary. Despite financial challenges, Catalina de Medrano's dowry (267 ducats) and business expertise supported Cabot, who granted her power of attorney in June 1524—a rare move for the time. Catalina de Medrano managed family finances, settling debts and handling business affairs, though she faced challenges like gender-related reluctance in transactions. Her family had long-standing connections with Spanish nobility, supplying fine cloth and goods to the royal court in the late 15th century.[27] Catalina de Medrano exemplified the resilience of Seville’s women, who often managed families and businesses during uncertain times. Her second marriage to Cabot, based on trust and respect, secured her daughter’s inheritance and maintained her vital role in navigating the complex social and financial challenges of the period.[27]

Remove ads

Reputation

From the later sixteenth century until the mid-nineteenth century, historians believed that Sebastian Cabot, rather than his father John, led the famous Bristol expeditions of the later 1490s, which resulted in the European discovery, or rediscovery after the Vikings, of North America. This error seems to have been attributed to Sebastian's accounts in his old age.[28] The result was that the influential geographical writer Richard Hakluyt represented his father John Cabot as a figurehead for the expeditions and suggested that Sebastian actually led them. When new archival finds in the nineteenth century demonstrated that this was not the case, Sebastian was denigrated, disparaged by Henry Harrisse, in particular, as a man who willfully appropriated his father's achievements and represented them as his own.[29] Because of this, Sebastian received much less attention in the twentieth century.[30] But other documentary finds, as summarized above, have demonstrated that he did lead some exploratory voyages from Bristol in the first decade of the sixteenth century.[9]

A. C. H. Smith wrote a biographical novel about him, Sebastian The Navigator (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1985).

Remove ads

Honors

- A 19th-century bronze relief of Cabot and Henry VII by William Theed is located in the British Houses of Parliament.[31]

- The Italian gunboat Sebastiano Caboto was named for Cabot.

Notes

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads