Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

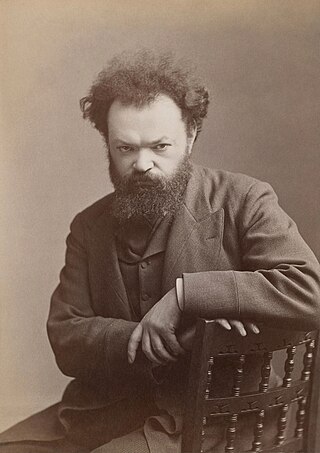

Sergei Stepniak

Russian revolutionary (1851–1895) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sergei Mikhailovich Stepniak-Kravchinskii (Russian: Сергей Михайлович Степняк-Кравчинский, Ukrainian: Сергій Степняк-Кравчинський; 13 July 1851 – 23 December 1895), known in 19th-century London revolutionary circles as Sergius Stepniak, was a Russian revolutionary of Ukrainian descent.[1]

He is mainly known for assassinating General Nikolai Mezentsov, chief of Russia's Gendarme corps and head of secret police,[2] with a dagger in the streets of St. Petersburg in 1878.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Kravchinskii, the son of an army doctor of Belarusian descent and a Ukrainian noblewoman, was born on 13 July [O.S. 1 July] 1851 in Novy Starodub, Aleksandriya uezd, Kherson Governorate, Russian Empire (now in Ukraine).[2][1] He received a liberal education, and when he left school, he went on to attend the Military academy and graduated from the Mikhailovsky Artillery Institute before joining the Imperial Russian Army.[3] He reached the rank of second lieutenant before resigning his commission in 1871.

Beginning of revolutionary activities

Kravchinskii's sympathy lay with the peasants, among whom he had lived during his boyhood in the country, which led him to develop democratic, and later revolutionary opinions. He joined the Circle of Tchaikovsky, a group of like-minded Narodnik philosophers and political activists whose ultimate goal was the "liberation of the people."[4] Stepniak became a member of the original St. Petersburg branch of the Circle, where he joined thirty other men and women of education, including Pyotr Kropotkin

As a member of this Circle, he began secretly to sow the sentiments of democracy and the ideals of the Narodniks among the peasants. To this end, he participated in a precursor to the Going to the People, when members of the Narodnik movement disguised themselves as peasants and laborers to spread the idea of revolution. Stepniak, accompanied by another member of the Circle, Dmitry Rogachev, appeared in a Tver village as woodcutters in the autumn of 1873. In November, they were tracked down by the rural police, but escaped at first, swearing to each other that they would dedicate their lives to the people.[4] The Circle was broken up and his teaching would cease soon after, ending with his arrest in 1874.

First emigration and return

Kravchinskii succeeded in making his escape, possibly being permitted to regain freedom on account of his youth, and immediately began a more vigorous campaign against autocracy. His sympathetic nature was influenced by indignation against the brutal methods adopted towards prisoners, especially political prisoners, and by the stern measures which the government of tsar Alexander II adopted in order to repress the revolutionary movement.[5] In late 1874 Kravchinskii moved to Switzerland , where he engaged in correspondence with Pyotr Lavrov, sharing with his idea of creating a popular magazine to be read by the village population. He later toured various European countries, meeting various dissidents from the Russian Empire, including Serhiy Podolynsky, a fellow native of Ukraine.[1]

In 1875, Kravchinskii left Geneva and went to the Balkans and joined the rising against the Turks in Bosnia in 1876, serving as an artilleryman;[1] he used that experience to write a manual on guerrilla warfare.[6] Kravchinskii dreamt of settling in Serbia after the end of the war, but the lack of revolutionary aims among the Balkan liberation movement forced him to abandon those plans.[1] In 1877 he joined the anarchist Errico Malatesta in his small rebellion in the Italian province of Benevento.[7][8] Arrested by Italian authorities after the failure of the uprising, he was threatened with death penalty, but regained his freedom as a result of a royal amnesty.[1] Kravchinskii returned to Russia in 1878, joining Zemlya i volya (Land and Liberty). Along with Nikolai Morozov and Olga Liubatovich edited the party journal.

Murder of Mezentsev and second emigration

Convinced that individual acts of political terrorism would convince Tsar Alexander II to introduce democratic reforms, on 16 August [O.S. 4 August] 1878 Kravchinskii assassinated General Nikolai Mezentsov,[9] the chief of the Gendarme corps and head of the country's secret police,[2] with a dagger in the streets of St Petersburg. Mezentsov had been active during the famous Trial of the 193, in which university students were threatened with treason charges for having committed "disobedience". Alexander the Second wished the accused to be given light sentences, until Mezentsov, then Chief of State Police, suggested that the punishment should be stricter. The emperor eventually changed the sentences to heavier ones, which became the motivation for Mezentsov to be assassinated by Kravchinskii.[10]

After the killing, Kravchinskii exposed himself to danger by remaining in Russia, staying in Saint Petersburg and writing articles for the underground Zemlya i Volya newspaper.[1] He left the country in the fall of 1878, settling for a short time in Switzerland, then a favourite resort of revolutionary leaders, and after a few years came to London. He was already known in England by his book, Underground Russia, which had been published in London in 1882.[11] In England he established the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom and the Russia Free Press (with an associated Russia Free Press Fund (RFPF)), linking with Karl Pearson, Wilfrid Voynich and Charlotte Wilson. He was also an editor for the Society's house organ, Free Russia. During that time, in order to evade persecution by Russian agents abroad, Kravchinskii adopted the pseudonym Stepniak ("steppe dweller"), which was related to his native land. During his stay abroad Kravchinskii supported himself through publications, and also worked as a teacher of Russian. He also read the poetry of Taras Shevchenko and taught his London friend Ethel Boole Ukrainian, which had been the native tongue of his mother. It was in Kravchinskii's London house that Ethel met her future husband Michał Wojnicz in 1890.[1]

Stepniak followed up Underground Russia with a number of other works on the condition of the Russian peasantry, on Nihilism, and on the conditions of life in Russia. The British socialist and Fabian Annie Besant reviewed Stepniak’s The Russian Storm-Cloud in her journal Our Corner in July 1886. She wrote: “I earnestly commend this work to my readers, as a book to be read and kept. The deep interest of its theme is sufficient to ensure its welcome among all who turn to the Russian Revolutionary party eyes of admiration and of love.”[12] His mind gradually turned from belief in the efficacy of violent measures to the acceptance of constitutional methods. In his last book, King Stork and King Log, Stepniak spoke with approval of the efforts of politicians on the Liberal side to effect, by argument and peaceful agitation, a change in the attitude of the Russian government towards various reforms.[11]

Stepniak constantly wrote and lectured, both in Great Britain and the United States, in support of his views, and his energy, added to the interest of his personality, won him many friends. He was chiefly identified with the Socialists in England and the Social Democratic parties on the Continent; but he was regarded by people of all opinions as an agitator whose motives had always been pure and disinterested.[11] Russian anarchist leader Peter Kropotkin, who knew Stepniak personally, testified as to his character:

He was a stranger to the feeling of fear; it was as foreign to him as colors are to a person born blind. He was ready to risk his life every moment. Egotism as well as narrow partisanship was unknown to him; he believed that in a movement to defeat oppression there are always parties and factions with differences of opinion,—"but let every party do its share in the work for the common good, the best it knows how"—he used to say—"and the result will be much greater for the cause [...]" He also could not understand why there should be strife among the various parties, since all are involved in the struggle against a common enemy. This was the result of his inborn instinct for justice. I have known but few people who have possessed this instinct developed to such a degree. [...] When he heard someone relating about an injustice, he was at once ready to annihilate the oppressor. I shall never forget the expression of his face, when I related to him the treatment our comrades had received in France and Italy. And yet he was kindness personified. Whoever knew him loved him. The children in Russia worshipped him. He spent some of the most enjoyable moments of his life in America where, surrounded by bright black faces, he taught in a negro school.[13]

Death and memorial service

Stepniak was killed by a train at a railway crossing at Woodstock Road, Chiswick, London, where he resided, on 23 December 1895.[11] At the time of his untimely death, Kravchinskii had been preparing the publication of a new novel.[1] In the previously cited memorial essay on Stepniak written by Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin he explained the tragic manner of his death:

Sergei Stepniak was killed by a train, about three hundred feet away from his house. He left his house about 10.30 in the morning, in order to visit a gathering of friends and comrades in Shepherd's Bush (London). A few bricklayers who knew him well saw him go by. He was absorbed in a book, which he read while walking. He had to cross a single track of a branch line, between Hammersmith and South Acton. The place was very dangerous; one has to cross the track hastily and very carefully. At first glance one would think he could make it in a single leap, but in reality one has to make about seven steps across the track, in order to be out of danger. The sharp turn prevents the pedestrian from noticing the oncoming of a train. When the engineer saw Stepniak crossing the track, he sounded the whistle; but before Stepniak had time to turn his head, the train knocked him down, killing him instantly.[13]

His body was cremated at Woking on 28 December[11] and the cremated remains deposited at Kensal Green Cemetery.

In the same memorial essay cited above, Kropotkin (who apparently was in attendance) describes the memorial ceremony:

The following Saturday the cremation of his body took place. Hundreds of his friends came to his house and walked to the Ravenscourt Park cemetery. At the Waterloo station, from where the train leaves for Wauking [sic], thousands of workingmen assembled with their banners, representing the societies and Labor Unions of various parts of London. Opposite the station, in a downpour of rain, speeches were held by English, Russian, Italian, German and Armenian friends, who were often interrupted by the loud sobs of the assembled. The manifestation was both magnificent and heart-breaking. I have seen funerals large in numbers, but I have never seen a funeral with so much deep grief and sorrow as was manifested by the mourners at the funeral of Sergei Stepniak. When the terrible accident happened, he was only 43 years of age, full of strength and courage, full of hope and belief in the future. [...] Hundreds of letters and telegrams received at his funeral, attested to his value to the Russian Revolutionary movement. He was its central figure.[14]

Remove ads

Legacy

His person became the inspiration for the main hero of Ethel Voynich's The Gadfly, and his publications influenced the works of Leo Tolstoy, Emile Zola and Vladimir Lenin. During the Soviet times, a museum dedicated to Kravchinskii functioned in his native village. One of the streets was named after him in the Ukrainian city of Kirovohrad (now Kropyvnytskyi).[1]

Published works

- Underground Russia. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1883.

- Russia Under the Tzars. Translated by William Westall. London: Ward & Downey, 1885.

- A Female Nihilist. Boston, Mass.: Benj. R. Tucker, 1885.

- The Russian Storm-Cloud or, Russia in Her Relations to Neighbouring Countries. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1886.

- The Russian Peasantry: Their Agrarian Condition, Social Life, and Religion. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1888.

- The Career of a Nihilist: A Novel. London: Walter Scott, 1889.

- King Stork and King Log: A Study of Modern Russia. London: Downey & Co., 1895.

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads