Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Water Margin

One of the Chinese Classic Novels From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

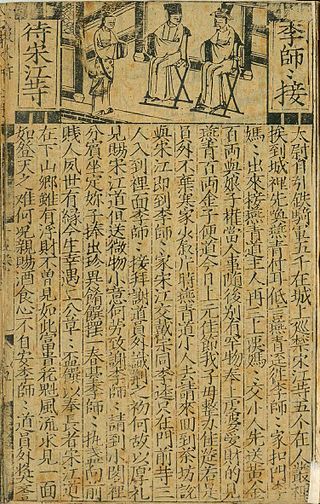

Water Margin (Chinese: 水滸傳; pinyin: Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn), also called Outlaws of the Marsh or All Men Are Brothers,[note 1] is a Chinese novel from the Ming dynasty that is one of the preeminent Classic Chinese Novels. Attributed to Shi Nai'an, Water Margin was one of the earliest Chinese novels written in vernacular Mandarin Chinese.[1]

Set during the Northern Song dynasty (around 1120), the story follows a group of 108 outlaws who gathers at Mount Liang (also known as Liangshan Marsh) to rebel against the government. Later they are granted amnesty and enlisted by the government to resist the nomadic conquest of the Liao dynasty and other rebels. While the book's authorship is traditionally attributed to Shi Nai'an (1296–1372), the first external reference to the novel only appeared in 1524 during the Jiajing reign of the Ming dynasty, sparking a long-lasting academic debate on when it was actually written and which historical events the author had witnessed that inspired him to write the book.[1]

The novel is considered one of the masterpieces of early vernacular fiction and Chinese literature.[2] It has introduced readers to some of the best-known characters in Chinese literature, such as Wu Song, Lin Chong, Pan Jinlian, Song Jiang and Lu Zhishen. Water Margin also exerted a significant influence on the development of fiction elsewhere in East Asia, such as on Japanese literature.[3][4]

Remove ads

Historical context and inspirations

Summarize

Perspective

Water Margin is based on the exploits of the outlaw Song Jiang and his 107 companions; framed in the story as the incarnations of 108 demons representing 108 stars (the 36 "heavenly spirits" (三十六天罡) and the 72 "earthly demons" (七十二地煞)). The activities of Song Jiang's group were recorded in the historical text History of Song in the annals of Emperor Huizong of Song, which states:

(When) the outlaw Song Jiang of Huainan and others attacked the army at Huaiyang, (the Emperor) sent generals to attack and arrest them. (The outlaws) infringed on the east of the capital (Kaifeng), Henan, and entered the boundaries of Chu (referring to present-day Hubei and Hunan) and Haizhou (covering parts of present-day Jiangsu). The general Zhang Shuye was ordered to pacify them.[5]

Zhang Shuye's biography further describes the activities of Song Jiang and the other outlaws, and tells they were eventually defeated by Zhang.[6]

A precursor and blueprint of Water Margin is a compilation of folk tales titled as Old Incidents in the Xuanhe Period of the Great Song Dynasty (大宋宣和遺事), where it also inserts the story of the treacherous ministers of the Song dynasty who controlled the government and caused great suffering to the people. It also serves as a comparison for the story of the heroes of Liangshan.[7][8] If it is counted with Gong Kai's Praise of the Thirty-six Men of Song Jiang' from the same period, both works also mentioned the name of Yan Qing (one of the outlaw characters in Water Margin), as one of the thirty-six rebel leaders of Song Jiang's group.[9] Furthermore, the archetype for Yan Qing's personality in the novel was suspected to be derived from Liang Xing (梁興), a Song general who fought against the Jin Dynasty.[10]

Folk stories about Song Jiang circulated during the Southern Song. The first known source to name Song Jiang's 36 companions was Miscellaneous Observations from the Year of Guixin (癸辛雜識) by Zhou Mi, written in the 13th century. Among the 36 of Song Jiang's companions, there are names like Lu Junyi, Guan Sheng, Ruan Xiao'er, Ruan Xiaowu, Ruan Xiaoqi, Liu Tang, Hua Rong and Wu Yong. Some of the characters who later became associated with Song Jiang also appeared around this time. They include Sun Li, Yang Zhi, Lin Chong, Lu Zhishen and Wu Song.[11]

According to Ning Jiayu, a Chinese language professor at Nankai University, one theory suggests that Shi Jin was inspired by a real-life figure named Shi Bin (史斌), a rebel leader from Shanxi who lived during the early Southern Song dynasty and was a subordinate of Song Jiang in his early years.[12]

Another outlaw figure allegedly inspired by a real person was Xie Bao.[13] This theory relies on classical era records of Sanchao beimeng huibian (三朝北盟會編). In this narration, the real Xie Bao was a minor rebel leader from Jizhou during the early Southern Song (ca. 1129, Jianyan era). In response to this rebellion, emperor Gaozong sent Han Shizhong, talented general with promising career, who managed to suppress these rebels group which led by Xie Bao and others.[14] This raw historical kernel fueled speculation by modern Chinese historian and textual critic Wang Liqi (王利器) that the figure was the real life inspiration for the fictionalized Liang Shan bandit hero.[15] However, other Chinese historical critics like Wang Yu and Li Dianyuan were skeptical towards Wang Liqi's theory of this legend-history fusion for lacking supporting evidence to prove that the historical Xie Bao fled from Dengzhou to Jeju, as this conjencture could support the claim that the real life rebel was indeed the inspiration for the fictionalized Xie Bao.[13]

Fang La, one of the primary antagonists in Water Margin, was inspired by the real-life rebel of the same name.[16] His rebellion was linked to the spread of Manichaeism in China during Song dynasty.[17][18][19] The rebellion which started by Fang La was portrayed as a prototypical "heretical uprising" in Chinese historiography.[20]

Both the Jiajing reign of the Ming dynasty (1521–1568) and the closing years of the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty (1360s) were marked by a chain of rebellions, which confused scholars a lot as to which of the two inspired the author, and hence when was the book written.[21]

According to Lu Xun, there was a large marshland at Mount Liang which existed since the Song dynasty, which served as inspiration for the base for Liangshan bandits.[22]

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

The opening episode in the novel is the release of the 108 Spirits, imprisoned under an ancient stele-bearing tortoise.[23]

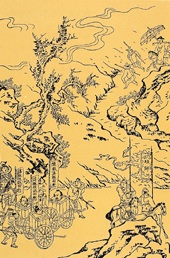

The next chapter describes the rise of Gao Qiu, one of the primary antagonists of the story. Gao abuses his status as a Grand Marshal by oppressing Wang Jin; Wang's father taught Gao a painful lesson when the latter was still a street-roaming ruffian. Wang Jin flees from the capital with his mother and by chance he meets Shi Jin, who becomes his apprentice. The next few chapters tell the story of Shi Jin's friend Lu Zhishen, followed by the story of Lu's sworn brother Lin Chong. Lin Chong is framed by Gao Qiu for attempting to assassinate him, and almost dies in a fire at a supply depot set by Gao's henchmen. He slays his foes and abandons the depot, eventually making his way to Liangshan Marsh, where he becomes an outlaw. Meanwhile, the "Original Seven", led by Chao Gai, rob a convoy of birthday gifts for the Imperial Tutor Cai Jing, another primary antagonist in the novel. They flee to Liangshan Marsh after defeating a group of soldiers sent by the authorities to arrest them, and settle there as outlaws with Chao Gai as their chief. As the story progresses, more people come to join the outlaw band, including military personnel and civil officials who grew tired of serving the corrupt government, as well as men with special skills and talents. Stories of the outlaws are told in separate sections in the following chapters. Connections between characters are vague, but the individual stories are eventually pieced together by chapter 60 when Song Jiang succeeds Chao Gai as the leader of the band after the latter is killed in a battle against the Zeng Family Fortress.

The plot further develops by illustrating the conflicts between the outlaws and the Song government after the Grand Assembly of the 108 outlaws. Song Jiang strongly advocates making peace with the government and seeking redress for the outlaws. After defeating the imperial army in a great battle at Liangshan Marsh, the outlaws eventually receive amnesty from Emperor Huizong. The emperor recruits them to form a military contingent and sends them on campaigns against invaders from the Liao dynasty and rebel forces led by Tian Hu, Wang Qing and Fang La within the Song dynasty's domain. Although the former outlaws eventually emerge victorious against the rebels and Liao invaders, the campaigns also lead to the tragic dissolution of the 108 heroes. At least two-thirds of them die in battle while the surviving ones either return to the imperial capital to receive honours from the emperor and continue serving the Song government, or leave and spend the rest of their lives as commoners elsewhere. Song Jiang himself is eventually poisoned to death by the "Four Treacherous Ministers" – Gao Qiu, Yang Jian, Tong Guan and Cai Jing.

Characters

The 108 Heroes (一百单八将) are at the core of the plot of Water Margin. Based on the Taoist concept that each person's destiny is tied to a "Star of Destiny" (宿星), the 108 Stars of Destiny are stars representing 108 demonic overlords who were banished by the deity Shangdi. Having repented since their expulsion, the 108 Stars are accidentally released from their place of confinement, and are reborn in the world as 108 heroes who band together for the cause of justice. They are divided into the 36 Heavenly Spirits and 72 Earthly Fiends.

Chapters

This outline of chapters is based on a 100 chapters edition. Yang Dingjian's 120 chapters edition includes other campaigns of the outlaws on behalf of Song dynasty, while Jin Shengtan's 70 chapters edition omits the chapters on the outlaws' acceptance of amnesty and subsequent campaigns.

The extended version includes the Liangshan heroes' expeditions against the rebel leaders Tian Hu and Wang Qing prior to the campaign against Fang La.[24]

Remove ads

Reception and themes

Summarize

Perspective

Water Margin, praised as an early "masterpiece" of vernacular fiction,[25] is renowned for the "mastery and control" of its mood and tone.[25] The novel is also known for its use of vivid, humorous and especially racy language.[25] However, it has been denounced as "obscene" by various critics since the Ming dynasty.[26]

"These seduction cases are the hardest of all. There are five conditions that have to be met before you can succeed. First, you have to be as handsome as Pan An. Second, you need a tool as big as a donkey's. Third, you must be as rich as Deng Tong. Fourth, you must be as forbearing as a needle plying through cotton wool. Fifth, you've got to spend time. It can be done only if you meet these five requirements."

"Frankly, I think I do. First, while I'm far from a Pan An, I still can get by. Second, I've had a big cock since childhood."

— Excerpt from the novel, translated by Sidney Shapiro[27]

According to Xu Yongqiang of the School of Humanities at Xi'an University of Electronic Science and Technology, there have been approximately 50 monographic series and over 1,000 research and analysis works on the Water Margin from the Ming and Qing dynasties to the present-day, demonstrating its immense influence and establishing "Water Margin Studies" as a prominent discipline of study.[28]

Some of the 108 outlaws internal dynamics exemplifies a key narrative style in Water Margin: strategic juxtaposition of contrasting personalities to heighten dramatic tension. As example, Shi Xiu's meticulous nature stands in sharp relief against Yang Xiong's rough-hewn demeanor, a pairing that underscores their differences and enriches the storytelling. This approach is a hallmark of the novel, evident in other pairings such as the forbearing Lin Chong and the bold Lu Zhishen, or the refined Song Jiang and the blunt Li Kui. Over time, such contrasts have evolved into a longstanding convention in literary expression. These subunits typically feature concise plots and limited casts of characters; the Yang Xiong and Shi Xiu subunit, spanning chapters 44 through 46, exemplifies this with its tightly knit episodes—the brothers' sworn alliance, the wife's infidelity, Shi Xiu's killing of his sister-in-law, and their eventual flight to Liangshan. Far from a mere linear progression, this subtheme employs deliberate alignments and transformations between units and subunits.[29]

Sinologist Lois M. Fusek also framed the parallel between Water Margin, which is revolutionary, glorifying bandits as divinely ordained agents of change; with the novel The Three Sui Quash the Demons' Revolt, which tone more reformist and traditional, deriding such figures—depicted as humble peddlers like noodle-vendors and cake-sellers—as absurd pretenders to heavenly mandate. This mockery underscores a pro-establishment stance, emphasizing swift suppression. Other than that, the temporal momentum complements spatial allusions of Three Suis with Water Margin's iconic locales and archetypes creates a satirical mirror-world between those two novels.[30]

Religious themes

The motif of pairings between 36 and 72 stars, possibly inspired from Dipper, were common among Chinese mythologies and folk tales, including Water Margin, which represented by the number of its protagonists.[31] The religious theme of these 108 demons that incarnated into the 108 Liangshan bandits apparently drew inspiration from the 36 heavenly spirits and 72 earth fiends that also appeared in a later Chinese vernacular novel titled Investiture of the Gods. In that novel, the 108 demons were gathered by Jiang Taigong to fight against King Zhou of Shang.[32] Liu Ts'un-yan added that the motif of 108 stars (36 spirits and 72 fiends representatives) constellation which appeared in both works were influenced by Buddhism and Taoism.[33]

Others analyzed Li Kui, one of the most savage Liangshan bandit characters, in more religious aspects, by quoting from the words of Luo Zhenren (a Taoist immortal in the novel who comments on the characters' fates) and a famous line from Laozi's Tao Te Ching (chapter 5): "天地不仁,以万物为刍狗 ("Heaven and Earth are impartial and treat all beings as disposable "straw dogs" used in rituals"). This portrays the spiritual character of Li Kui as being representative of the chaotic force of nature, blending divine indifference with animalistic instincts.[34][35]

Furthermore, both Victor Purcell[36] and Joseph W. Esherick have recorded that Water Margin—along with The Romance of the Three kingdoms and Investiture of the Gods— were quite influential for the religious Belief of the radical Boxer movement in shaping their ideology,[37] which became the reason for Qing government to ban the novel in 1799.[36]

Tao Chengzhang (d. 1911) attributed the surge of religious movements like the White Lotus Societies in north China and the Heaven and the Earth Society in the south was due to the influences of the novels Investiture of the Gods and Water Margin respectively. He writes: "Throughout the area of Shandong, Shanxi and Henan [that is, the north] there is no one who does not believe [zunxin] in the Investiture of the Gods story. Throughout the area of Jiangsu, Zhe-jiang, Fujian and Guangzhou [the south] there is no one who does not venerate [chongbai] the book, Water Margin".[38]

In the novel, the Liangshan bandits patronized the goddess Jiutian Xuannü (九天玄女 lit. "Mystic Goddess of the Ninth Heaven"), who instructed Song Jiang and hisngroup to adhere the Taoism ethics on sexual desire.[39] The physical appearance of the goddess has been described in a poem that appears in the Rongyu Tang (容與堂) edition,[40] the 100-chapter version of the novel with Li Zhi's commentary.[41]

In Ming dynasty (1368–1644), lesser-known female deities surpassed the elite Queen Mother of the West in vernacular novels like Water Margin and Investiture of the Gods. Rooted in Chinese folk religion, likely inspiring syncretic sectarian icons such as the Venerable Mother Guanyin. This interplay of literature and belief idealized transcendent feminine archetypes, while exposing era-specific tensions around embodied womanhood. The narrative democratized goddess worship via accessible epics—rebellion in Water Margin's bandits and cosmic wars in Investiture's divinities—infused with maternal authority. The 16th-century Eternal Mother from White Lotus writings fused folk piety with millenarianism. As Daniel L. Overmyer observes, northerners canonization of Investiture of the Gods and southerners veneration of Water Margin, illustrates their symbiotic role in faith: a subversive tool empowering the illiterate through heroic divinity. These "post-menopausal" goddesses embody pure motherliness—nurturing wisdom without childbirth's mess or sexual desire's pitfalls—aligning with Confucian purity yet excising femininity's "negatives" like vulnerability and passion. However, this desexualized ideal reinforces gender binaries, reflecting Ming anxieties over female sexuality amid orthodoxy-heterodoxy clashes.[42]

Political themes

According to Li Shi (1471–1538), the authorial rationale behind the counterfactual victory of the Southern Song over the Liao at the end of the novel stems from the patriotic motivations of the novel's alleged authors, Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong—both of whom lived during the Yuan dynasty.[44] Furthermore, Water Margin is politically influential throughout the following China's history, from the rebellion of Zhang Xianzhong;[45] the Tiandihui adoption of the novel as their movement's guideline;[46] late Qing/Republican eras recast as patriotic literature; to the 1970s Cultural Revolution vilification of Song's "capitulationism" via revised editions for factional purges.[47]

Some argue that the novel's theme of revolt against authority became popular during turbulent time of Ming dynasty, others argue that Water Margin became popular during the Yuan as the common people (predominantly Han Chinese) resented the Mongol rulers.[21] Chongzhen Emperor of the Ming dynasty, acting on the advice of his ministers, banned the book.[48] Chen Chen, a Ming loyalist, saw the novel as an expression of Song resistance to the Mongol invaders in the Yuan dynasty.[47]

The tremendous influence of the novel on Late Ming peasant rebellions also noteworthy.[49][50] Historian James Bunyan Parsons argues that Water Margin may have had some influence on Zhang Xianzhong's rebellion. Based on Parsons' hypothesis, Mark R. E. Meulenbeld points out that Zhang Xianzhong was recorded using the novels as a source for emulation, as he quoted an early Qing observer who ascribes Zhang's fondness with the novel, "The shrewdness of Zhang Xianzhong included him making people read books like Three Kingdoms and Water Margin every day..."[45] It was attested by citation from Perry Link, that during the end of Ming dynasty period, rebels in Hebei used slogans such as "killing the rich to help the poor" and "carrying out the Dao on behalf of Heaven", which popularized by both Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms as a form of "remedial protest".[51]

Zuo Maodi (左懋第) (1601–1645), a Ming dynasty vice minister of war, viewed the Water Margin as a book that taught people to be criminals. He believed that if the book was not banned, it would impact the societal atmosphere negatively. The court accepted his suggestion and banned the book for a time.[52]

The Jurchen chief and Khan Nurhaci learned Chinese military and political strategies from Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[53][54]

Yu Wanchun instead gave his negative assessment as he saw its polemical tone and encouragement of brigandage and revolt as a potential threat to the state.[47] Late Ming dynasty scholar Jin Shengtan criticized Shi Nai'an as not motivated by traditional scholarly venting resentment through writing but as a way of leisure.[55] Jin also questioned the inconsistency of Song Jiang's characterization according to Confucian morality.[56]

In the aftermath of Qing dynasty's literary inquisition by Qianlong emperor, the novel saw another boom of mass popularity and a wave of massive publications followed. This has attracted the concern from a Qing official named Ding Richang, who points out its polemical social effect, although he did not outright actively pursuing to ban the book.[57]

The ethic of outlaw loyalty permeated even the Post-1853 grand Taiping Heavenly Kingdom shifted toward Water Margin-inspired ethics, emphasizing blind loyalty to leaders and "yi"-style camaraderie. This suggests a tactical evolution from religious millenarianism to pragmatic, bandito-like solidarity, blending ancient monarchical fealty with subversive brotherhood.[46] According to Frederic Wakeman, the superior fraternity which formed by Taiping leaders such as Heavenly King Hong Xiuquan, East King Yang Xiuqing, North King Wei Changhui, and Wing King Shi Dakai was partly modelled from the brotherhood of the Liangshan outlaws from the novel.[58] Graciela de la Lama stated that the main concept of the politico-literary "model" which borrowed by the Taipings was the concepts of "Loyalty and Fraternity" (忠義) which followed by the Liangshan outlaws in the book.[59]

Elizabeth J. Perry investigation with Anhui University scholars has led her to conclude that the Nian Rebellion's slogan banner, "Preparing the Way for Heaven, killing the rich to relieve the poor; Alliance Leader of the Great Chinese, Chang", which borrowed from the White Lotus sect, was obviously inspired by the Water Margin, emulating the outlaw heroes of Liangshan.[60][61]

The Baguadao sect used banners with the inscription "Entrusted by Heaven to Prepare the Way" during Eight Trigrams uprising of 1813, a reference to the Water Margin novel.[62]

Meanwhile, for early-modern era, Water Margin has long and broad influence beyond their narrative as inspiration for various subversive movements. The Triad (organized crime), enigmatic fraternal orders which born in the Qing era's underbelly as a subversive force, has blended messianic zeal (e.g., their slogan "Oppose the Qing and restore the Ming") with demonological rituals for political legitimacy. Their adoption of Water Margin's "yi" (unquestioning comradeship) rejects Confucian norms of duty and righteousness, positioning them as outlaw heroes. This unorthodoxy, combined with ritualistic elements, frames them as agents of political rebellion rather than mere criminals.[46]

Furthermore, Chinese revolutionary figure Song Jiaoren (1882–1913) idealizes the "heroes of the forest" (bandit archetypes from Water Margin) as embodying Robin Hood-esque justice and chivalry. Despite critiquing their criminality and foreign alliances, he invokes ethnic Han solidarity ("fellow descendants of our Yellow Emperor") to humanize them, using the novel as a lens for nationalist empathy.[46] Novelist Zhang Henshui felt that Water Margin's emphasis on the patriotism as Liangshan outlaws join Song government troops against the Jin invaders, could inspire anti-Japanese feeling among the Chinese living in Shanghai.[63]

Secret societies and criminal organizations during Republic era also adopted such code of Water Margin's martial fraternity, such as the Green Gang From Shanghai[64][65][66] and the Blue Shirts Society, an unofficial secret police of Chiang Kai-shek regime. One of Blue Shirts founding member, Dai Li, has developed the orrganization based on the value of heroism and outlaw martial artists of the Water Margin, where the recruits drawn from the lower strata of society: jugglers, wrestlers, itinerant entertainers, journeymen traders, jailers, executioners, thieves, and gangsters.[67]

Water Margin also found its legs in the history of Chinese Communist Party, where the novel enjoyed the party's endorsement since 1930s for their political aim.[68] Liu Kwang-ching even noted that Water Margin was one of Mao Zedong's favorite readings.[46] European sinologists Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals noted the influence of Water Margin in the political dynamic after the Cultural Revolution in China, where in the mid-1970s the radical Gang of Four failed propaganda tactics against the moderate reformer Deng Xiaoping; where the said Gang of Four weaponized literature in political purges. In particular, the radicals' nadir trying to make allusion of Deng with Song Jiang. Their jargon of "Criticize Water Margin, denounce Song Jiang" campaign unfurled across winter 1975–76 university walls in a blizzard of big-character posters. Song Jiang, the Liangshan chieftain whose tale revolt ends in treacherous capitulation to imperial pardon, stood accused as archetype of Deng's ilk as Opportunist defeatist. However, the allusion campaign of the Gang of Four backfired as Mao Zedong's immersion into the Water Margin story ends him favored Deng, as he drew personal conclusion that fictional surrender of the Liangshan towards the government as a litmus for real-world fidelity; thus ending with Deng Xiaoping emerge victorious from the political struggle.[69] Even as later Mao got change of heart in late 1973, when Mao started to distance himself from Water Margin allegorical campaigns and see the act of Song Jiang's capitulation negatively; Deng was quick to take note and shifted gears of his campaign in August 1975 into criticizing the rightist revisionism in line with Mao's vision. Meanwhile, his rivals, the aforementioned Gang of Four kept on their wrong track with their campaign, this time by focusing their energy to criticize Lin Biao and Confucius, failed to understand about Mao's change of mind.[70]

Furthermore, other reason of Mao's Suddenly announce Shui Hu Zhuan pi pan (水滸傳 批判), or Criticism of the Water Margin, in 1973 was a moved to curtail the possibility of armed coup by the Lin Biao's faction. As Mao said, "The rebels Water Margin fought against dishonest officials but did not oppose the emperor. Later they capitulated. Take note, revisionism may emerge in China."[71]

Social themes

There are two major social themes in Water Margin. The first one is yi (義), or "unquestioned loyalty",[46] a moral code which Andrew H. Plaks translated as "good," "valor," "honor," "generosity," or "nobility".[72] According to Catherine Vance Yeh, its more complete form is zhong yi (忠義), which translated as "unperturbed by love". This means the Youxia (Chinese knight-errant) motif in Water Margin expected one to focus on male bonding and unmoved by romance or sex.[73] Li Wenzhi concluded in his book, Popular revolts of the late Ming, that the concept of yi which was supposed to be a regulatory code for the bandit chieftains, rebel and secret society leaders swore brotherhood together.[51]

The second one is hǎo hàn (好漢),[74][75] an antinomianism masculinity moral code. The hǎo hàn code values freedom and brotherhood above everything else, Even if it means one should sacrifice his own wife and children. Portrayals of female hǎo hàn also existed in the novel, but they are often depicted as bloodthirsty as their male counterparts.[76] John Christopher Hamm encapsulated the polemic of Water Margin's ambiguous response from society for its youxia and hǎo hàn themes, as shown by Jin Shengtan's begrudging admiration yet deconstructive commentary; Chen Chen's 1664 version of sequel (Shuihu Houzhuan); and Yu Wanchun's version of sequel (Dangkou zhi).[47] Scholar Pang Zengyu viewed it as "greenwood heroes" (lùlín háojié 綠林豪傑) ethic—a code of companionship and justice immortalized within Chinese, Russian, and Korean settlers amid imperial decline and colonial flux; such theme infused Manchurian folklore with a moral code that distinguished noble hao han (real men) from ignoble tufei (dirt robbers). Thus, lecturer Ed Pulford extends this transnationality, paralleling Liangshan's bandit-iconization with Slavic analogs such as the molodets ("fine young lad") who opposed Tsar Ivan the Terrible in the 16th-century ballads, as per Maureen Perrie; or the Hajduks, the Haydamaks, and the Druzhinas.[77]

Susan L. Mann writes that the "desire for male camaraderie" is "far from a mere plotline," for it is a basic theme of this and other classic novels. She places the novel's male characters in a tradition of men's culture of mutual trust and reciprocal obligation, such as figures known as the Chinese knight-errant. In this regard, she quoted the words of Sima Qian, the Han dynasty historian, devoted a section to biographies: "Their words were always sincere and trustworthy, and their actions always quick and decisive. They were always true to what they promised, and without regard to their own persons, they would rush into dangers threatening others." She finds such figures in this and other novels, such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West, all of which dramatized the "empathic emotional attraction between men who appreciate and play off against one another's complementary qualities."[78]

Licentious and treacherous women are another recurring theme. Modern critics have debated whether Water Margin is misogynistic.[79][80][81] Most beautiful women in the novel are depicted as immoral and cruel, and they are often involved in schemes against the protagonists. Among them is Pan Jinlian, the sister-in-law of Wu Song, who has later become an archetypal femme fatale and one of the most notorious villainesses of Chinese culture. On the other hand, the few "good" women in the story, like Sun Erniang and Gu Dasao, are not particularly noted for their beauty, or are even described as being plain or ugly. The leader of the outlaws, Song Jiang admonishes: "Any outlaw that meddles with women is contemptible."[82]

Critics offer various explanations for Water Margin's prejudice against women. Most common among modern Chinese critics is the patriarchal society of the Imperial China.[83][84] Sun Shuyu of The Chinese University of Hong Kong argues that the author(s) of Water Margin intentionally vilified women in order to discipline their would-be-outlaw audiences.[85]

The novel is notable for its gruesome and often gory and excessive depictions of violence. Some of the protagonists of the novel engage in "wanton killing, excessive retribution, and various forms of cannibalism. When celebrating a victory, they sometimes "share their enemies' flesh piece by piece, an action combining cannibalism with lingchi", the slow slicing of somebody to death.[86] This type of violent imagery in the novel is mentioned in a "causal tone", with human flesh being eaten not just "in acts of revenge", but also "as a way of living".[87] Noting that the outlaws celebrated in the novel were nevertheless widely regarded as "heroes and heroines" over centuries, educator William Sin states that one cannot divide "the meanings of [their] actions" from "the cultural background under which they [were] performed" and that it would be "hasty" to project concepts and values of today "onto the situation of a distant culture" where they may not have applied.[88]

Liu Zaifu decries the novel as cultural poison, arguing that Water Margin, together with Romance of the Three Kingdoms, has sown people's "moral downfall".[89] There also a popular anecdotal quip in China which says, "The young should not read The Water Margin while the old should not read The Romance of the Three Kingdoms", criticizing its violent and machismo effects on young male audiences.[68] By the late 19th century, the reformer Liang Qichao criticized Water Margin along with another novel, Dream of the Red Chamber as "incitement to robbery and lust".[90] Liangyan Ge called it a book "full of scenes of brutality and sadism , representing only one extremity of Chinese Culture". [91]

Lu Xun felt disturbed with the scale of brutality shown in the novel, in particular, by Li Kui.[92][93] However, being a seemingly simple-minded yet popular character, there are numerous studies for how his personality is shown in the novel. Li Kui is considered as a representative of the peasant classes' real-world struggles, highlighting class conflict in a feudal society. Majority of the people believe Li Kui is a person with incomplete mental faculties leading to psychological distortion; albeit some sees Li Kui as a subversive anti-hero in the novel's later arcs, where the outlaws debate surrendering to the government. His alleged "madness" masks deep wisdom and resistance, making him a "wise fool" (智若愚, appearing foolish but profoundly insightful)—a trope in literature where apparent stupidity hides truth-telling.[34][35]

Remove ads

Authorship

Summarize

Perspective

While the book's authorship is attributed to Shi Nai'an (1296–1372), there is an extensive academic debate on what historical events the author had witnessed that inspired him to write the book, which forms a wider debate on when the book was written.[1] The first external reference of this book, which dated to 1524 during a discussion among Ming dynasty officials, is a reliable evidence because it presents strong falsifiability.[1] Other scholars put the date to the mid-14th century, sometime between the fall of the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty and the early Ming dynasty.[1]

Since fiction was not at first a prestigious genre in the Chinese literary world, authorship of early novels was often not carefully attributed and may be unknowable. The authorship of Water Margin is still in some sense uncertain, and the text in any case derived from many sources and involved many editorial hands. While the novel was traditionally attributed to Shi Nai'an, of whose life not much is reliably known, recent scholars think that the novel, or portions of it, may have been written or revised by Luo Guanzhong (the author of Romance of the Three Kingdoms).[94]

Shi Nai'an

Many scholars believe that the first 70 chapters were indeed written by Shi Nai'an; however the authorship of the final 30 chapters is often questioned, with some speculating that it was instead written by Luo Guanzhong, who may have been a student of Shi.[94] Another theory, which first appeared in Gao Ru's Baichuan Shuzhi (百川書志) during the Ming dynasty, suggests that the whole novel was written and compiled by Shi, and then edited by Luo.

Shi drew from oral and written texts that had accumulated over time. Stories of the Liangshan outlaws first appeared in Old incidents in the Xuanhe period of the great Song dynasty (大宋宣和遺事) and had been circulating since the Southern Song dynasty, while folk tales and opera related to Water Margin have already existed long before the novel itself came into existence. This theory suggests that Shi Nai'an gathered and compiled these pieces of information to write Water Margin.

Luo Guanzhong

Some believe that Water Margin was written entirely by Luo Guanzhong. Wang Daokun (汪道昆), who lived during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor in the Ming dynasty, first mentioned in Classification of Water Margin (水滸傳敘) that: "someone with the family name Luo, who was a native of Wuyue (Yue (a reference to the southern China region covering Zhejiang), wrote the 100-chapter novel." Several scholars from the Ming and Qing dynasties, after Wang Daokun's time, also said that Luo was the author of Water Margin. During the early Republican era, Lu Xun and Yu Pingbo suggested that the simplified edition of Water Margin was written by Luo, while the traditional version was by Shi Nai'an.[citation needed]

However, Huikang Yesou (惠康野叟) in Shi Yu (識餘) disagree with Wang Daokun's view on the grounds that there were significant differences between Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms, therefore these two novels could not have been written by the same person.

Hu Shih felt that the draft of Water Margin was done by Luo Guanzhong, and could have contained the chapters on the outlaws' campaigns against Tian Hu, Wang Qing and Fang La, but not invaders from the Liao dynasty.[95]

Shi Hui

Another candidate is Shi Hui (施惠), a nanxi (southern opera) playwright who lived between the late Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty. Xu Fuzuo (徐復祚) of the Ming dynasty mentioned in Sanjia Cunlao Weitan (三家村老委談) that Junmei (君美; Shi Hui's courtesy name)'s intention in writing Water Margin was to entertain people, and not to convey any message. During the Qing dynasty, Shi Hui and Shi Nai'an were linked, suggesting that they are actually the same person. An unnamed writer wrote in Chuanqi Huikao Biaomu (傳奇會考標目) that Shi Nai'an's given name was actually "Hui", courtesy name "Juncheng" (君承), and he was a native of Hangzhou. Sun Kaidi (孫楷第) also wrote in Bibliography of Chinese Popular Fiction that "Nai'an" was Shi Hui's pseudonym. Later studies revealed that Water Margin contained lines in the Jiangsu and Zhejiang variety of Chinese, and that You Gui Ji (幽闺记), a work of Shi Hui, bore some resemblance to Water Margin, hence the theory that Water Margin was authored by Shi Hui.[citation needed]

Guo Xun

Early scholars attributed the authorship to Guo Xun (郭勛), a politician who lived in the Ming dynasty. Shen Defu (沈德符), a late Ming dynasty scholar, mentioned in Wanli Yehuo Bian (萬曆野獲編) that Guo wrote Water Margin. Shen Guoyuan (沈國元) added in Huangming Congxin Lu (皇明從信錄) that Guo mimicked the writing styles of Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin to write Guochao Yinglie Ji (國朝英烈記). Qian Xiyan (錢希言) also stated in Xi Gu (戲嘏) that Guo edited Water Margin before. Hu Shih countered in his Research on Water Margin (水滸傳新考) that Guo Xun's name was used as a disguise for the real author of Water Margin. Dai Bufan (戴不凡) had a differing view, as he suspected that Guo wrote Water Margin, and then used "Shi Nai'an" to conceal his identity as the author of the novel.[96]

Remove ads

Editions and translations

Summarize

Perspective

The textual history of the novel is extraordinarily complex for there are early editions of varying lengths, different parts, and variations. The scholar Scott Gregory comments that the text could be freely altered by later editors and publishers who also could add prefaces or commentaries.[98] Not until the early 20th-century were there studies which began to set these questions in order, and there is still disagreement.[99] The earliest components of the Water Margin (in manuscript copies) were from the late 14th century. A printed copy dating from the Jiaqing reign (1507–1567) titled Jingben Zhongyi Zhuan (京本忠義傳), is preserved in the Shanghai Library.[100][101] The earliest extant complete printed edition of Water Margin is a 100-chapter version published in 1589.[102] An edition, with 120 chapters and an introduction by Yang Dingjian (楊定見), has been preserved from the reign of the Wanli Emperor (1573–1620) in the Ming dynasty. Yet other editions were published in the early Qing dynasty.

The most widely read version is a truncated recension published by Jin Shengtan in 1643, reprinted many times,[99] which became the standard text for later editions and most translations.[103] Jin provided three introductions that praised the novel as a work of genius and inserted commentaries into the text that explained how to read the novel. He cut matter that he thought irrelevant, reduced the number of chapters to 70 by turning chapter 1 into a prologue, and added an ending in which all 108 heroes are executed.[104]

The various editions can be classified into simplified and complex. The simplified editions, edited for less sophisticated audiences, can contain all the events but in less detail. There is no way of knowing whether a simplified edition came before or was derived from another by adding or cutting text.[104]

Simplified editions

The simplified editions include stories on the outlaws being granted amnesty, followed by their campaigns against the Liao dynasty, Tian Hu, Wang Qing and Fang La, all the way until Song Jiang's death. At one point, the later chapters were compiled into a separate novel, titled Sequel to Water Margin (續水滸傳), which is attributed to Luo Guanzhong.

Known simplified editions of Water Margin include:

- A 115-chapter edition, Masterpieces of the Han and Song dynasties (漢宋奇書)

- A 110-chapter edition, Chronicles of Heroes (英雄譜)

- A 164-chapter edition, combined with Sequel to Water Margin

- A 109-chapter edition, 2-Carved Heroes' Compendium

- A 124-chapter version, Daodao Tang Edition

- A 104-chapter edition, Water Margin Chronicles Commentary

Complex editions

The complex editions are more descriptive and circulated more widely than their simplified counterparts. The three main versions of the complex editions are a 100-chapter, a 120-chapter and a 70-chapter edition. The most commonly modified parts of the complex editions are the stories on what happened after the outlaws are granted amnesty.

- 100-chapter edition: Includes the outlaws' campaigns against the Liao dynasty and Fang La after they have been granted amnesty.

- 120-chapter edition: An extended version of the 100-chapter edition, includes the outlaws' campaigns against Tian Hu and Wang Qing (chapters 91 to 110).

- 71-chapter edition: Edited by Jin Shengtan in the late Ming dynasty, this edition uses chapter 1 as a prologue and ends at chapter 71 of the original version, and does not include the stories about the outlaws being granted amnesty and their campaigns.

- There is another 120-chapter version known as Mei's Collection Water Margin. The first 70 chapters of this version are consistent with Jin Shengtan's Guanhuatang version, but the last 50 chapters are completely different from other versions. There is no plot of recruiting and Liangshan still fights against the government. There is controversy about the authenticity of the last 50 chapters of this version and the value of this version itself, with many people believing that the last 50 chapters were forged by Mei Jihe.

Non-English translations

Water Margin has been translated into many languages. The book was translated into Manchu as Möllendorff: Sui hū bithe.[105] Japanese translations date back to at least 1757, when the first volume of an early Suikoden (Water Margin rendered in Japanese) was printed.[106] Other early adaptations include Takebe Ayakari's 1773 Japanese Water Margin (Honcho suikoden),[107] the 1783 Women's Water Margin (Onna suikoden),[108] and Santō Kyōden's 1801 Chushingura Water Margin (Chushingura suikoden).[109]

In 1805, Kyokutei Bakin released a Japanese translation of the Water Margin illustrated by Hokusai. The book, called the New Illustrated Edition of the Suikoden (Shinpen Suikogaden), was a success during the Edo period and spurred a Japanese "Suikoden" craze.

In 1827, publisher Kagaya Kichibei commissioned Utagawa Kuniyoshi to produce a series of woodblock prints illustrating the 108 heroes in Water Margin. The 1827–1830 series, called 108 Heroes of the Water Margin or Tsuzoku Suikoden goketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori, catapulted Kuniyoshi to fame. It also brought about a craze for multicoloured pictorial tattoos that covered the entire body from the neck to the mid-thigh.[110]

Following the great commercial success of the Kuniyoshi series, other ukiyo-e artists were commissioned to produce prints of the Water Margin heroes, which began to be shown as Japanese heroes rather than the original Chinese personages.

Among these later series was Yoshitoshi's 1866–1867 series of 50 designs in Chuban size, which are darker than Kuniyoshi's and feature strange ghosts and monsters.[111] A recent Japanese translation is Suikokuden 水滸伝. Translated by Yoshikawa Kojiro; Shimizu Shigeru. Iwanami Shoten. 16 October 1998.

The book was first translated into Thai in 1867, originally in Samud Thai (Thai paper book) format, consisting of 82 volumes in total. It was printed in western style in 1879 and distributed commercially by Dan Beach Bradley, an American Protestant missionary to Siam.

Jacques Dars translated the 70 chapter version into French in 1978, reprinted several times.[112]

English translations

71-chapter version

- Pearl S. Buck was the first English translator of the entire 71-chapter version. Titled All Men are Brothers and published in 1933.[113] It was revised in 1937 including the Introduction/Foreword attributed to Shi Naian. The book was well received by the American public. However, it was also criticised for its errors, such as the mistranslation of Lu Zhishen's nickname "Flowery Monk" as "Priest Hua".[citation needed]

- In 1937, another complete translation appeared, titled Water Margin, by J. H. Jackson, edited by Fang Lo-Tien.[114] A translation of Jin's Preface was published in 1935 by the Shanghai journal, The China Critic.[115].

- The J. H. Jackson translation was revised, restored, and updated by Edward H. Lowe in 2009 and published by Tuttle Classics.

100-chapter version

Later translations of the 71-chapter version include Chinese-naturalised scholar Sidney Shapiro's Outlaws of the Marsh (1980) that also does not include the verse. However, as it was published during the Cultural Revolution, this edition received little attention then.[116] It is a translation of a combination of both the 71-chapter and 100-chapter versions.

120-chapter version

The most recent translation, titled The Marshes of Mount Liang (1994-2002), by Alex and John Dent-Young, is a five-volume translation of the 120-chapter version. It includes a prologue but omits the foreword by Shi Nai'an and some passages related to the official details of the Ming dynasty.[117]

Differences

These translations differ in the selection of texts and completeness. The Jackson and the revised Buck translations of 1937 contain the foreword attributed to Shi Nai'an. The Shapiro translation omits the prologue, the foreword, and most of the poems. The Dent-Young translation omits the author's foreword and the passages concerning the Ming dynasty administration and the translators admitted to compromising some details and retaining inconsistencies in their Brief Note on the Translation.

Remove ads

Sequels and spinoffs

Summarize

Perspective

There are several noteworthy direct sequels and spinoffs to the Water Margin. Some tell subsequent stories of the heroes fighting the Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty, infighting of the heroes, or moving to Siam.[118][119]

Jin Ping Mei

Jin Ping Mei is an erotic novel of manners written under the pen-name Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng (蘭陵笑笑生) ("The Scoffing Scholar of Lanling") in the latter half of the 16th century. The novel is framed as a spinoff of Water Margin based on the story of Wu Song avenging his brother in Water Margin, but the focus is on Ximen Qing's sexual relations with other women, including Pan Jinlian. The intervening sections, however, differ in almost every way from Water Margin.[120] In the course of the novel, Ximen has 19 sexual partners, including his six wives and mistresses, and a male servant.[121]

Pan Jinlian became an archetypal femme fatale and one of the most notorious villainesses of classical Chinese culture.[122] The influential author Lu Xun, writing in the 1920s, called it "the most famous of the novels of manners" of the Ming dynasty, and reported the opinion of the Ming dynasty critic, Yuan Hongdao, that it was "a classic second only to Water Margin." He added that the novel is "in effect a condemnation of the whole ruling class."[123] Pan Jinlian also appeared to be based on the false rumors a real namesake lady who had a sharply different personality. The reputation of real-life Pan Jinlian was badly affected by the fictional Pan Jinlian and this incident also caused a rift between Pan family and Shi family (the family of Shi Nai'an, author of Water Margin) for a long time until descendants of Shi family made an official apology in 2009.[124][125]

Shuihu Houzhuan

A sequel to Water Margin titled Shuihu Houzhuan (水滸後傳) (The Later Story of Water Margin) that authored by Chen Chën, a writer from the early era Qing dynasty and native of Zhejiang, was released In 1664.[126]: 155 [127]: 102 [128]

Shuihu Houzhuan comprises 40 chapters, organized into two parts. Its plot diverges somewhat from the original Water Margin. The first 30 chapters focus on the chaotic state of China, with the Liangshan heroes gradually assembling, reaching a total of 32 by the 29th chapter. The final 10 chapters depict the heroes' decision to journey to a foreign land, where they encounter a wise monarch and benevolent people, leading to a joyful conclusion.[126]: 156 Shuihu Houzhuan also introduces new characters such as Hua Rong's son Hua Fengchun (花逢春), Xu Ning's son Xu Sheng (徐晟) and Huyan Zhuo's son Huyan Yu (呼延鈺).[128]

Plot

The story started with Ruan Xiaoqi, falsely accused of treason by corrupt officials Tong Guan and Cai Jing after wearing Fang La's discarded dragon robe. Returning to Shijie Village, he kills Cai Jing's ally Zhang Ganban and flees, joining former Liangshan heroes like Hu Cheng and Luan Tingyu in banditry.[126]: 155–156

Meanwhile, Li Jun and seven others, disillusioned with China's chaos after the Northern Song's fall, sail to Siam (historical Thailand), conquer Jin'ao Island, and ally themselves with the royal family. Thirty-two surviving Liangshan heroes regroup in Shandong and Hebei and later join Li Jun in Siam during a siege.[126]: 155–156 In the chapter 35; Japan Borrows Troops, Sparking Conflict; Qingni Island Incites Rebellion and Mobilizes Forces", An army of 10,000 Japanese warriors embarked from Satsuma Domain and Ōsumi provinces aboard 300 warships to aid a usurper in Siam against the Liangshan heroes. The figure leading the Japanese army is called Kanpaku. The Kanpaku is depicted as eight shaku (approximately 2.4 meters) tall and riding an elephant. He also commands a naval warfare unit known as the 'Kurooni' (Black Ghosts). However, the entire army meets its end by freezing to death due to Gongsun Sheng's socery.[128] The Liangshan heroes manages to defeat the usurper Gong Tao, and Li Jun becomes the king of Siam.[126]: 155–156

Later, Li Jun rescues Southern Song Emperor Gaozong, who pardons the heroes and recognizes Li Jun's rule. Under Li Jun, Siam adopts Chinese influences, and the 32 heroes marry and settle happily.[126]: 155–156

Receptions and themes

The author, Chen Chen, was known for his resentment towards rule of Qing and joined the Jingyin Poetry society, together with those who loyal to Ming like Gu Yanwu. Later, he published the sequel in 1664.[126]: 155 Chen Chen took the pen name "Yandang Shanqiao" and giving commentary for the published edition and claimed the original script was written by an anonymous "loyalist of Song" who lived during the early years of Yuan dynasty rule.[129]: 242

According to Hu Shih, the theme of this sequel work reflects Chen Chen's grief and anger about the fall of Ming dynasty, which he analogize with the fall of Northern Song to the Yuan dynasty, which is the backdrop era of the Water Margin story.[130]: 755、759、760 The novel also continues to promote the theme of loyalty and resistance to foreign aggression through rebellion. However, the methods of these reformed Liangshan heroes in Siam is very different from that of the original group, as they resorted to less violence, held family happiness in high regards and awareness about the importance of civil government system; which followed by setting their end goal in establishing a foundation in Siam. In the end, the theme expresses the hopes, fears and resentment of the Ming loyalists, and the anti-Qing movement.[129]: 242–243

Furthermore, the book's poems reveal the author's desire to establish new utopia for Ming's loyalists to a foreign land may allude to their hopes on Zheng Chenggong's regime in Taiwan.[131]

Overall, Hu Shih does not rate this sequel work with high praise, with the exception of some of its chapters which stand out from others, such as "Zhongmu County's Elimination of Traitors" in volume 22. The book also described Yan Qing's visit to Emperor Huizong of Song , which was also written in a sad and touching way, far surpassing the other chapters.[130]: 765、767 Sinologist Ellen Widmer believed that the literary value of the Shuihu Houzhuan was mixed and not enough to be included in the list of first-rate classics. The work directly influenced the 19th-century Japanese novel Chun Shuo Gong Zhang Yue by Takizawa Bakin.[131]

Hou Shuihu Zhuan

A sequel novel titled Hou Shuihu Zhuan (後水滸傳; Water Margin Transmission), attributed to the pseudonymous author "Master of the Blue Lotus Chamber" (Qing Lian Shi Zhu Ren, 青蓮室主人) was written during the 17th century, and it spans 45 chapters across 10 volumes and was first printed in the Qianlong era (1736–1795) by Su Zheng Tang (素政堂).

Dang Kou Zhi

Dang Kou Zhi (蕩寇志 The Tale of Eliminating Bandits), which also known for its alternate title Jie shuihu quanzhuan (結水滸全傳 Terminating the Complete Saga of the Water Margin)[74], is a novel written by Qing dynasty novelist Yu Wanchun (俞萬春) during the reign of the Daoguang Emperor. The story follows the end of original Water Margin runs im chapter 70. The book runs from Chapter 71 to Chapter 140, totaling 70 chapters, with a concluding chapter titled "The Conclusion to the Son.".[132] It took him 22 years to complete the book.[133]

Yu Wanchun disagreed that the Liangshan outlaws are loyal and righteous heroes, and was determined to portray them as ruthless mass murderers and destroyers, hence he wrote Dang Kou Zhi. As a result, he portrays the Liangshan outlaws here as the antagonists, only to be eliminated by the designated protagonists.[134]

The protagonist of this novel is Chen Xizhen, a Taoist and martial arts master who turned outlaw, and ended opposing the Liangshan outlaws led by Song Jian.[134][135][136] The novel, which starts at the Grand Assembly of the 108 outlaws at Liangshan Marsh, tells of how the outlaws plundered and pillaged cities before they are eventually eliminated by government forces led by Zhang Shuye (張叔夜) and his lieutenants Chen Xizhen (陳希真) and Yun Tianbiao (雲天彪).[132]

Due to its pro-establishment and anti-rebellion theme, this sequel was supported and endorsed by government of Qing. However, the Taiping rebels disliked the nuance of the novel and ordered the burning of the book in every place they occupied.[137][133]

According to Roland Altenburger, this novel may be the inspiration of Ernü Yingxiong Zhuan novel.[74]

Fictional stories about Yue Fei

Some spinoffs of Water Margin were intertwined with Song General Yue Fei.[citation needed]

Chapters 31 to 45 of Hou Shuihu Zhuan novel depicted general Yue Fei, portrayed as a divine general, suppresses the rebels at Caibo Bridge. Defeated, the heroes ascend to heaven, enlightened by a karmic epilogue emphasizing redemption through reincarnation.[138]

The Qing dynasty writer Qian Cai wrote the life story of Yue Fei and the outlaws Lin Chong and Lu Junyi in a Sin off story titled novel written by Qian Cai titled General Yue Fei (Chinese: 說岳全傳) (1684), which consisted of 80 chapters, stated that the latter were former students of the general's martial arts tutor, Zhou Tong.[139] However, literary critic C. T. Hsia commented that the connection was a fictional one created by the author.[140] Additionally, the novla mentions about the partiicipation of one of the Liangshan outlaws, Huyan Zhuo, in a campaign under the lead of Yue Fei defending against thr invasion by the Jin dynasty. The novel tell the death of Huyan Zhuo on the hands of a Jin prince, Wuzhu, amid combat.[141]

The Republican era folktale Swordplay Under the Moon, by Wang Shaotang, further intertwines Yue Fei's history with the outlaws by adding Wu Song to the list of Zhou's former students.[142] The tale is set in the background of Wu Song's mission to Kaifeng, prior to the murder of his brother. Zhou tutors Wu in the "rolling dragon" style of swordplay during his one-month stay in the capital city. It also said that Zhou is a sworn brother of Lu Zhishen and shares the same nickname with the executioner-turned-outlaw Cai Fu.[143]

More Modern literary fictional biography that linked Zhou Tong with the Liangshan outlaws was Iron Arm, Golden Sabre novel in 1986, a Modern novel prequel to The Story of Yue Fei.[citation needed] This novel later adapted into a ten volume Lianhuanhua-style comic book called The Legend of Zhou Tong in 1987.[144]

Can Shui Hu

A sequel novel which titled Can Shui Hu, or Remnant Water Margin (殘水滸), was written by Cheng Shanzhi (pen name of Cheng Qingyu, 程慶餘; 1880–1942);[145] a novelist associated with the Southern Society (南社) literary group. It was serialized in 1933 in the New Jiangsu Daily (《新江蘇日報》) under the pseudonym "Yi Su" (一粟), and reprinted by Heilongjiang People's Publishing House in 1997. The novel exists and is a well-documented sequel to the 70-chapter edition of Water Margin. It composed 16 chapters that followed the original simple Water Margin version of 70 chapters, spanning from chapter 71 to 86.[citation needed]

The narrative picks up directly from Lu Junyi's prophetic nightmare, followed by the split of the Liangshan brotherhood due to ideological rifts. the leaders divide into two camps over the issue whether they should surrender to the government and seek pardon, or keep being outlaws. Lu Junyi's faction (pro-surrender) seeks alliance with Northern Song border general named Zong Shidao (種師道). Song Jiang's faction, which composed of 36 core members, refused the integration aspiration by Lu Junyi, and clinging to their autonomy as outlaws. Some of the Liangshan heroes fell during the ensuing civil war, such as Li Kui's death by Hu Sanniang and Dong Ping's poisoning by Cheng Wanli's Daughter. After Liangshan's defeat, Song Jiang's faction flees to Haizhou (海州), where they are captured by Zhang Shuye (張叔夜), the historical Song general who subdued Song Jiang in 1121 (per History of Song). Lu's faction, honoring old bonds, petitions the court to spare Song's life—sparing execution but dooming the remnants to further tragedy. The book culminates in total annihilation: Surrenders lead to executions or exile, battles claim the rest, and Song Jiang is ultimately also implied being killed.[145]

With the exception of Zhang Shuye and Chen Xiuzhen (who also the protagonist of Dang Kou Zhi.[135]), there are not many notable new characters in this novel. Yet, the personality of certain legacy characters are given more focus, such as Song Jiang 's cunning and Wu Yong's wisdom. Chen Xizhen and his daughter, Chen Liqing, were persecuted by the government, particularly by Gao Qiu and Gao Yanei. Both father and daughter were forced to fled the capital. However, Chen Xizhen also hated the Liangshan heroes and refused to join them. Later, Chen Xizhen occupied a village and gathered people to start an uprising, until he accepted the amnesty and surrendered to the government. He joined forces with Zhang Shuye and others in the suppression of Liangshan outlaws, until they manage to eliminate the group.[134]

Chen Xizhen serves as the antithesis of Song Jiang and Liangshan outlaws, where despite having similar background with them as renegade of the state, he refused to join them, and even participated in the bandits' final elimination.[146] This reflects the contradictory and tangled psychology of Yu Wanchun, who was a fan of "Water Margin" and wanted to inherit Jin Shengtan 's ideas to attack the rebels.[146]

Remove ads

Influence and adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

Literature

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of Chinese fiction and drama to the literary culture of early modern Japan. The rise to ubiquitous prominence of Chinese texts such as Shuihu zhuan, Xiyou ji (Journey to the West), and the short fiction of Feng Menglong (1574–1646) was a gradual occurrence.... From a certain vantage point, the Chinese novel Shuihu zhuan [Water Margin] is a ubiquitous presence in the literary and visual culture of early modern Japan. Indeed, Japanese engagement with Shuihu zhuan is nearly coeval with the establishment of Tokugawa hegemony itself, as evidenced by the presence of a 1594 edition of the novel in the library of the Tendai abbot and adviser to the fledgling Tokugawa regime, Tenkai. Tenkai's death in 1643 provides us with a lower limit for dating the novel's importation into Japan, demonstrating the remarkable rapidity with which certain Chinese texts found their way into Japanese libraries.

Frank Chin's novel, Donald Duk, contains many references to the Water Margin. Song Jiang and Li Kui make several appearances in the protagonist's dreams.

Rise of the Water Margin[148] (水滸再起) is a novel launched in 2022 by the American author Christopher Bates in which all of the Chinese characters and their approximate character arcs are 21st century modernizations of people in The Water Margin. In this cyber-thriller, the characters of Lin Chong, Lu Da, Gao Qiu, Gao Yanei, Zhang Zhenniang, Fu An, Cai Jing, Chai Jin, Wang Lun, Zhu Gui, Zhao Ji, Li Shishi and many others appear. The location of Liangshanpo is a deserted ghost city known to its investors as Mount Liang Swamp, repurposed as a hacker enclave.

Eiji Yoshikawa wrote Shin Suikoden (新水滸伝), which roughly translates to "New Tales from the Water Margin".

The Water Outlaws, a novel by S. L. Huang, is a gender-flipped version of the story in which many of the outlaws are queer women.[149][150][151]

In addition to its colossal popularity in China, Water Margin has been identified as one of the most influential works in the development of early modern Japanese literature.[3][152][4]

Comics

Water Margin is referred to in numerous Japanese manga, such as Tetsuo Hara and Buronson's Fist of the North Star, and Masami Kurumada's Fūma no Kojirō, Otokozaka and Saint Seiya. In both works of fiction, characters bearing the same stars of the Water Margin characters as personal emblems of destiny are featured prominently. A Japanese manga called Akaboshi: Ibun Suikoden, based on the story of Water Margin, was serialised in Weekly Shonen Jump.

A Hong Kong manhua series based on Water Margin was also created by the artist Lee Chi Ching. A reimagined series based on Water Margin, 108 Fighters, was created by Andy Seto.

Between 1978 and 1988, the Italian artist Magnus published four acts of his work I Briganti, which places the Water Margin story in a setting that mixes Chinese, Western and science fiction (in Flash Gordon style) elements. Before his death in 1996, the four completed "acts" were published in a volume by Granata Press; two following "acts" were planned but never completed.

In 2007, Asiapac Books published a graphic narrative version of portions of the novel.[153]

Film

Most film adaptations of Water Margin were produced by Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers Studio and mostly released in the 1970s and 1980s. They include: The Water Margin (1972),[154][155] directed by Chang Cheh and others; Delightful Forest (1972), directed by Chang Cheh again and starring Ti Lung as Wu Song;[156] Pursuit (1972), directed by Kang Cheng and starring Yueh Hua as Lin Chong; All Men Are Brothers (1975), a sequel to The Water Margin (1972) directed by Chang Cheh and others; and Tiger Killer (1982), directed by Li Han-hsiang and starring Ti Lung as Wu Song again.[157]

Other non-Shaw Brothers production include: All Men Are Brothers: Blood of the Leopard, also known as Water Margin: True Colours of Heroes (1992), which centers on the story of Lin Chong, Lu Zhishen and Gao Qiu, starring Tony Leung Ka-fai, Elvis Tsui and others;[158] and Troublesome Night 16 (2002), a Hong Kong horror comedy film which spoofs the story of Wu Song avenging his brother.

Television

Television series directly based on Water Margin include: Nippon Television's The Water Margin (1973), which was later released in other countries outside Japan;[159][160] Outlaws of the Marsh (1983), which won a Golden Eagle Award; CCTV's The Water Margin (1998), produced by Zhang Jizhong and featuring fight choreography by Yuen Woo-ping; All Men Are Brothers (2011), directed by Kuk Kwok-leung and featuring actors from mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Animations adapted from Water Margin include: Giant Robo: The Animation (1992), an anime series based on Mitsuteru Yokoyama's manga series; Outlaw Star (1998), another cartoon series which makes several references to the novel; Hero: 108 (2010), a flash animated series produced by various companies and shown on Cartoon Network. Galaxy Divine Wind Jinraiger, an anime in the J9 Series planned for a 2016 broadcast, has also cited Water Margin as its inspiration.[161][162]

The 2004 Hong Kong television series Shades of Truth, produced by TVB, features three characters from the novel who are reincarnated into present-day Hong Kong as a triad boss and two police officers respectively.

Video games

Video games based on the novel include Konami's console RPG series Suikoden and Koei's strategy game Bandit Kings of Ancient China. Other games with characters based on the novel or were partly inspired by it include: Jade Empire, which features a character "Black Whirlwind" who is based on Li Kui; Data East's Outlaws Of The Lost Dynasty, which was also released under the titles Suiko Enbu and Dark Legend; Shin Megami Tensei: Imagine. There is also a beat em' up game Shuǐhǔ Fēngyún Chuán (Chinese: 水滸風雲傳; lit. 'Water and Wind'), created by Never Ending Soft Team and published by Kin Tec in 1996.[163] It was re-released for the Mega Drive and in arcade version by Wah Lap in 1999.[citation needed] An English version titled "Water Margin: The Tales of Clouds and Winds" by Piko Interactive translated and released in 2015. Some enemy sprites are taken from other beat 'em ups and modified, including Knights of the Round, Golden Axe and Streets of Rage.[citation needed]

In the 8th canto of the 2023 video game Limbus Company, A faction based on the 108 heroes appears as both allies and antagonists.[164]

Music

Yan Poxi, a Pingju form of the story focused on the concubine Yan Poxi, was performed by Bai Yushuang and her company in Shanghai in the 1930s.

Water Marginised (水滸後傳) (2007) is a folk reggae narrative by Chan Xuan. It tells the story of a present-day jailbird who travels to Liangshan Marsh in hope of joining the outlaw band, only to find that Song Jiang and his men have all taken bureaucratic jobs in the ruling party.

"108 Heroes" is a three-part Peking Rock Opera (first shown in 2007, 2011 and 2014 respectively) formed through a collaborative effort between the Hong Kong Arts Festival, the Shanghai International Arts Festival, Taiwan Contemporary Legend Theater, and the Shanghai Theater Academy. The show combines traditional Peking Opera singing, costumes, martial arts and dance with elements of modern music, costume and dance.[165]

Other

The temple fair in Southern Taiwan Song Jiang Battle Array is based on the acrobatic fighting from Water Margin.

Characters from the story often appear on Money-suited playing cards, which are thought to be the ancestor of both modern playing cards and mahjong tiles. These cards are also known as Water Margin cards (水滸牌).

The trading card game Yu-Gi-Oh! has an archetype based on the 108 heroes known as the "Fire Fist" (known as "Flame Star" in the OCG) (炎えん星せい, Ensei) where the monsters aside from Horse Prince, Lion Emperor, and Spirit are based on those heroes.

Remove ads

Appendix

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads