Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

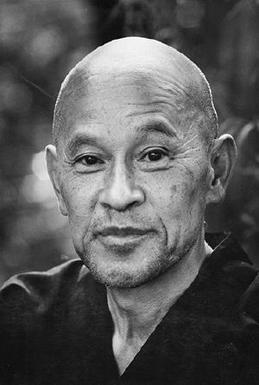

Shunryū Suzuki

Japanese Buddhist monk who popularized Zen in the US From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Shunryu Suzuki (鈴木 俊隆 Suzuki Shunryū, dharma name Shōgaku Shunryū 祥岳俊隆, often called Suzuki Roshi; May 18, 1904 – December 4, 1971) was a Sōtō Zen monk and teacher who helped popularize Zen Buddhism in the United States, and is renowned for founding the first Zen Buddhist monastery outside Asia (Tassajara Zen Mountain Center).[1] Suzuki founded San Francisco Zen Center which, along with its affiliate temples, comprises one of the most influential Zen organizations in the United States. A book of his teachings, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, is one of the most popular books on Zen and Buddhism in the West.[2][3][4]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Childhood

Shunryu Suzuki was born May 18, 1904, in Kanagawa Prefecture southwest of Tokyo, Japan.[5] His father, Butsumon Sogaku Suzuki, was the abbot of the village Soto Zen temple.[5] His mother, Yone, was the daughter of a priest and had been divorced from her first husband for being too independent. Shunryu grew up with an older half-brother from his mother's first marriage and two younger sisters. As an adult he was about 4 feet 11 inches (1.5 m) tall.[6]

His father's temple, Shōgan-ji, was located near Hiratsuka, a city on Sagami Bay about fifty miles southwest of Tokyo. The temple income was small and the family had to be very thrifty.[5]

Suzuki became aware of his family's financial plight when he began school. Suzuki was kind and sensitive, but prone to quick outbursts of anger. He was ridiculed by the other boys because of his shaved head and because he was the son of a priest. He preferred to spend his time in the classroom rather than on the schoolyard and was always at the top of his class. The teacher told him he would become a great man if he left Kanagawa Prefecture and studied hard.

Apprenticeship

In 1916, 12-year-old Suzuki decided to train with a disciple of his father, Gyokujun So-on Suzuki.[5] So-on was Sogaku's adopted son and abbot of Sogaku's former temple Zoun-in. His parents initially thought he was too young to live far from home but eventually allowed it.

Zoun-in is in a small village called Mori, Shizuoka in Japan. Suzuki arrived during a 100-day practice period at the temple and was the youngest student there. Zoun-in was a larger temple than Shōgan-ji.

At 4:00 each morning he arose for zazen. Next he would chant sutras and begin cleaning the temple with the others. They would work throughout the day and then, in the evenings, they all would resume zazen. Suzuki idolized his teacher, who was a strong disciplinarian. So-on often was rough on Suzuki but gave him some latitude for being so young.

When Suzuki turned 13, on May 18, 1917, So-on ordained him as a novice monk (unsui).[5] He was given the Buddhist name Shogaku Shunryu,[5] yet So-on nicknamed him Crooked Cucumber for his forgetful and unpredictable nature.

Shunryu began again attending upper-elementary school in Mori, but So-on did not supply proper clothes for him. He was the subject of ridicule. In spite of his misfortune he didn't complain. Instead he doubled his efforts back at the temple.

When Shunryu had first come to Zoun-in, eight other boys were studying there. By 1918, he was the only one who stayed. This made his life a bit tougher with So-on, who had more time to scrutinize him. During this period Suzuki wanted to leave Zoun-in but equally didn't want to give up.

In 1918 So-on was made head of a second temple, on the rim of Yaizu, called Rinso-in. Shunryu followed him there and helped whip the place back in order. Soon, families began sending their sons there and the temple began to come to life. Suzuki had failed an admissions test at the nearby school, so So-on began teaching the boys how to read and write Chinese.

So-on soon sent his students to train with a Rinzai master for a while. Here Shunryu studied a very different kind of Zen, one that promoted the attainment of satori through the concentration on koans through zazen. Suzuki had problems sitting with his koan. Meanwhile, all the other boys passed theirs, and he felt isolated. Just before the ceremony marking their departure Suzuki went to the Rinzai teacher and blurted out his answer. The master passed Suzuki; later Shunryu believed he had done it simply to be kind.

In 1919, at age 15, Suzuki was brought back home by his parents, who suspected mistreatment by So-on. Shunryu helped out with the temple while there and entered middle school. Yet, when summer vacation came, he was back at Rinso-in and Zoun-in with So-on to train and help out. He didn't want to stop training.

In school Suzuki took English and did quite well. A local doctor, Dr. Yoshikawa, hired him to tutor his two sons in English. Yoshikawa treated Suzuki well, giving him a wage and occasional advice.

Higher education

In 1924 Shunryu enrolled in a Soto preparatory school in Tokyo[5] not far from Shogan-ji, where he lived on the school grounds in the dorm. From 1925 to 1926 Suzuki did Zen training with Dojun Kato in Shizuoka at Kenko-in. He continued his schooling during this period. Here Shunryu became head monk for a 100-day retreat, after which he was no longer merely considered a novice. He had completed his training as a head monk.[7]

In 1925 Shunryu graduated from preparatory school and entered Komazawa University, the Soto Zen university in Tokyo.[5] During this period he continued his connections with So-on in Zoun-in, going back and forth whenever possible.

Some of his teachers here were discussing how Soto Zen might reach a bigger audience with students and, while Shunryu couldn't comprehend how Western cultures could ever understand Zen, he was intrigued.

On August 26, 1926, So-on gave Dharma transmission to Suzuki.[5] He was 22.[5] Shunryu's father also retired as abbot at Shogan-ji this same year, and moved the family onto the grounds of Zoun-in where he served as inkyo (retired abbot).

Later that year Suzuki spent a short time in the hospital with tuberculosis, but soon recovered. In 1927 an important chapter in Suzuki's life was turned. He went to visit a teacher of English he had at Komazawa named Miss Nona Ransom, a woman who had taught English to such people as the last emperor of China, Pu-yi, and more so his wife, the last empress of China, Jigoro Kano (the Founder of Judo), the children of Chinese president Li Yuanhong, and some members of the Japanese royal family. She hired him that day to be a translator and to help with errands. Through this period he realized she was very ignorant of Japanese culture and the religion of Buddhism. She respected it very little and saw it as idol worship. But one day, when there were no chores to be done, the two had a conversation on Buddhism that changed her mind. She even let Suzuki teach her zazen meditation. This experience is significant in that Suzuki realized that Western ignorance of Buddhism could be transformed.

On January 22, 1929, So-on retired as abbot of Zoun-in and installed Shunryu as its 28th abbot. Sogaku would run the temple for Shunryu. In January 1930 a ten'e ceremony was held at Zoun-in for Shunryu. This ceremony acknowledged So-on's Dharma transmission to Shunryu, and served as a formal way for the Soto heads to grant Shunryu permission to teach as a priest. On April 10, 1930, at age 25, Suzuki graduated from Komazawa Daigakurin with a major in Zen and Buddhist philosophy, and a minor in English.

Suzuki mentioned to So-on during this period that he might be interested in going to America to teach Zen Buddhism. So-on was adamantly opposed to the idea. Suzuki realized that his teacher felt very close to him and that he would take such a departure as an insult. He did not mention it to him again.

Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji

Upon graduation from Komazawa, So-on wanted Shunryu to continue his training at the well known Soto Zen temple Eihei-ji in Fukui Prefecture. In September 1930 Suzuki entered the training temple and underwent the Zen initiation known as tangaryo. His mother and father stayed on at Zoun-in to care for his temple in his absence.

Eihei-ji is one of the largest Zen training facilities in Japan, and the abbot at this time was Gempo Kitano-roshi. Prior to coming to Japan, Kitano was head of Soto Zen in Korea. He also was one of the founders of Zenshuji, a Soto Zen temple located in Los Angeles, California. Suzuki's father and Kitano had a tense history between them.[8] Sogaku had trained with Kitano in his early Zen training and felt that he was such a high priest due to familial status and connections. Shunryu did not see this in Kitano, however. He saw a humble man who gave clear instruction, and Shunryu realized that his father was very wrong in his assessment.

Often monks were assigned duties at the monastery to serve certain masters. Shunryu was assigned to Ian Kishizawa-roshi, a well known teacher at the time who had previously studied under two great Japanese teachers: Sōtan Oka and Bokusan Nishiari. He was a renowned scholar on Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō, and was also an acquaintance of his father from childhood.

Kishizawa was strict but not abusive, treating Suzuki well. Suzuki learned much from him, and Kishizawa saw a lot of potential in him. Through him Suzuki came to appreciate the importance of bowing in Zen practice through example. In December Suzuki sat his first true sesshin for 7 days, an ordeal that was challenging initially but proved rewarding toward the end. This concluded his first practice period at Eihei-ji.

In September 1931, after one more practice period and sesshin at Eihei-ji, So-on arranged for Suzuki to train in Yokohama at Sōji-ji. Sōji-ji was the other main Soto temple of Japan, and again Suzuki underwent the harsh tangaryo initiation. Sojiji was founded by the great Zen master Keizan and had a more relaxed atmosphere than Eihei-ji. At Sōji-ji Suzuki travelled back to Zoun-in frequently to attend to his temple.

In 1932 So-on came to Sōji-ji to visit with Shunryu and, after hearing of Suzuki's contentment at the temple, advised him to leave it. In April of that year Suzuki left Sōji-ji with some regret and moved back into Zoun-in, living with his family there. In May he visited with Ian Kishizawa from Eiheiji and, with So-on's blessing, asked to continue studies under him. He went to Gyokuden-in for his instruction, where Kishizawa trained him hard in zazen and conducted personal interviews with him.

Sometime during this period Suzuki married a woman who contracted tuberculosis. The date and name of the woman is unknown, but the marriage was soon annulled. She went back to live with her family while he focused on his duties at Zoun-in.

Suzuki reportedly was involved with some anti-war activities during World War II, but according to David Chadwick, the record is confusing and, at most, his actions were low-key.[9] However, considering the wholesale enthusiastic support for the war expressed by the entire religious establishment in Japan at the time, this fact is significant in showing something of the character of the man.

San Francisco Zen Center

On May 23, 1959, Shunryu Suzuki arrived in San Francisco to attend to Soko-ji, at that time the sole Soto Zen temple in San Francisco. He was 55.[5] Suzuki took over for the interim priest, Wako Kazumitsu Kato. Suzuki was taken aback by the Americanized and watered-down Buddhism practiced at the temple, mostly by older immigrant Japanese. He found American culture interesting and not too difficult to adjust to, even commenting once that "if I knew it would be like this, I would have come here sooner!" He was surprised to see that Sokoji was previously a Jewish synagogue (at 1881 Bush Street, now a historic landmark). His sleeping quarters were located upstairs, a windowless room with an adjoining office.

At the time of Suzuki's arrival, Zen had become a hot topic amongst some groups in the United States, especially beatniks. Particularly influential were several books on Zen and Buddhism by Alan Watts. Word began to spread about Suzuki among the beatniks through places like the San Francisco Art Institute and the American Academy of Asian Studies, where Alan Watts was once director. Kato had done some presentations at the academy and asked Suzuki to come join a class he was giving there on Buddhism. This sparked Suzuki's long-held desire to teach Zen to Westerners.

The class was filled with people wanting to learn more about Buddhism, and the presence of a Zen master was inspiring for them. Suzuki had the class do zazen for 20 minutes, sitting on the floor without a zafu and staring forward at the white wall. In closing, Suzuki invited everyone to stop in at Sokoji for morning zazen. Little by little, more people showed up each week to sit zazen for 40 minutes with Suzuki on mornings. The students were improvising, using cushions borrowed from wherever they could find them.

The group that sat with Suzuki eventually formed the San Francisco Zen Center with Suzuki. The Zen Center flourished so that in 1966, at the behest and guidance of Suzuki, Zentatsu Richard Baker helped seal the purchase of Tassajara Hot Springs in Los Padres National Forest, which they called Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. In the fall of 1969, they bought a building at 300 Page Street near San Francisco's Lower Haight neighborhood and turned it into a Zen temple. Suzuki left his post at Sokoji to become the first abbot of one of the first Buddhist training monasteries outside Asia. Suzuki's departure from Sokoji was thought to be inspired by his dissatisfaction with the superficial Buddhist practice of the Japanese immigrant community and his preference for the American students who were more seriously interested in Zen meditation, but it was more at the insistence of the Sokoji board, which asked him to choose one or the other (he had tried to keep both roles). Although Suzuki thought there was much to learn from the study of Zen in Japan, he said that it had grown moss on its branches, and he saw his American students as a means to reform Zen and return it to its pure zazen- (meditation) and practice-centered roots.

Suzuki died on December 4, 1971, presumably from cancer.[10]

Publications

A collection of his teishos (Zen talks) was published in 1970 in the book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind during Suzuki's lifetime.[11] His lectures on the Sandokai are collected in Branching Streams Flow in the Darkness, edited by Mel Weitsman and Michael Wenger and published in 1999.[12] Edward Espe Brown edited Not Always So: Practicing the True Spirit of Zen which was published in 2002.[13]

A biography of Suzuki, titled Crooked Cucumber, was written by David Chadwick in 1999.[14]

Remove ads

Lineage

| Shunryu Suzuki (1904—1971)[15] | |

| Zentatsu Richard Baker (born 1936) shiho 1971 | Hoitsu Suzuki (born 1939) |

|

|

Remove ads

Quotations

- "In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, in the expert's mind there are few."[16]

Books

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Ed. Trudy Dixon. Weatherhill, 1970. ISBN 0-834-80079-9

- Branching Streams Flow in the Darkness: Zen Talks on the Sandokai 1st ed. Eds. Mel Weitsman and Michael Wenger. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0-520-21982-1

- Not Always So: Practicing the True Spirit of Zen. Ed. Edward Espe Brown. HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0-060-95754-9

- Zen is Right Here. Shambhala, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59030-491-4

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. Shambhala, 2011. ISBN 978-1-59030-849-3

- "To Shine One Corner of the World: moments with Shunryu Suzuki / the students of Shunryu Suzuki". Ed. David Chadwick. Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 0-7679-0651-9 (Out of print - same as Zen is Right Here)

- Zen Is Right Now: More Teaching Stories and Anecdotes of Shunryu Suzuki. Ed. David Chadwick. Shambhala, 2021. ISBN 978-1-611809-14-5

- Crooked Cucumber: the Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki. by David Chadwick. Harmony, 2000. ISBN 978-0767901055

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads