Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Śūraṅgama Sūtra

Sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra (Chinese: 首楞嚴經; pinyin: Shǒuléngyán jīng, Sūtra of the Heroic March) (Taisho no. 945) is a Mahayana Buddhist Sūtra that has been influential across most forms of East Asian Buddhism, where it has traditionally been included as part of Chinese-language Tripitakas. In the modern Taisho Tripitaka, it is placed in the Esoteric Sūtra category (密教部).[1] The sūtra's Śūraṅgama Mantra is widely recited in China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam as part of temple liturgies.[2][3]

In Chinese Buddhism, it is a major subject of doctrinal study and the mantra revealed within the sūtra remains a regular part of the daily liturgy chanted in all Chinese Buddhist monasteries. It is particularly important in the Chinese Chan tradition, including both Linji and Caodong lineages, and the Chinese Pure Land Buddhist tradition (where it is considered a central scripture).[4][5] In Korean Buddhism, it also remains a major subject of study in Sŏn monasteries).[6][7][4] In Japanese Buddhism, the mantra revealed in the sūtra is chanted across the three main Zen traditions of Rinzai, Sōtō and Ōbaku. The doctrinal outlook of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is that of Buddha-nature, Yogacara thought, and esoteric Buddhism.

The sūtra was translated into Tibetan during the late eighth to early ninth century and other complete translations exist in Tibetan, Mongolian and Manchu languages (see Translations).

Remove ads

Title

Summarize

Perspective

Śūraṅgama means "heroic valour",[8] "heroic progress", or "heroic march" in Sanskrit. The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is not to be confused with the similarly titled Śūraṅgama Samadhi Sūtra (T. 642 首楞嚴三昧經; Shǒuléngyán Sānmèi Jīng) which was translated by Kumārajīva (344–413).

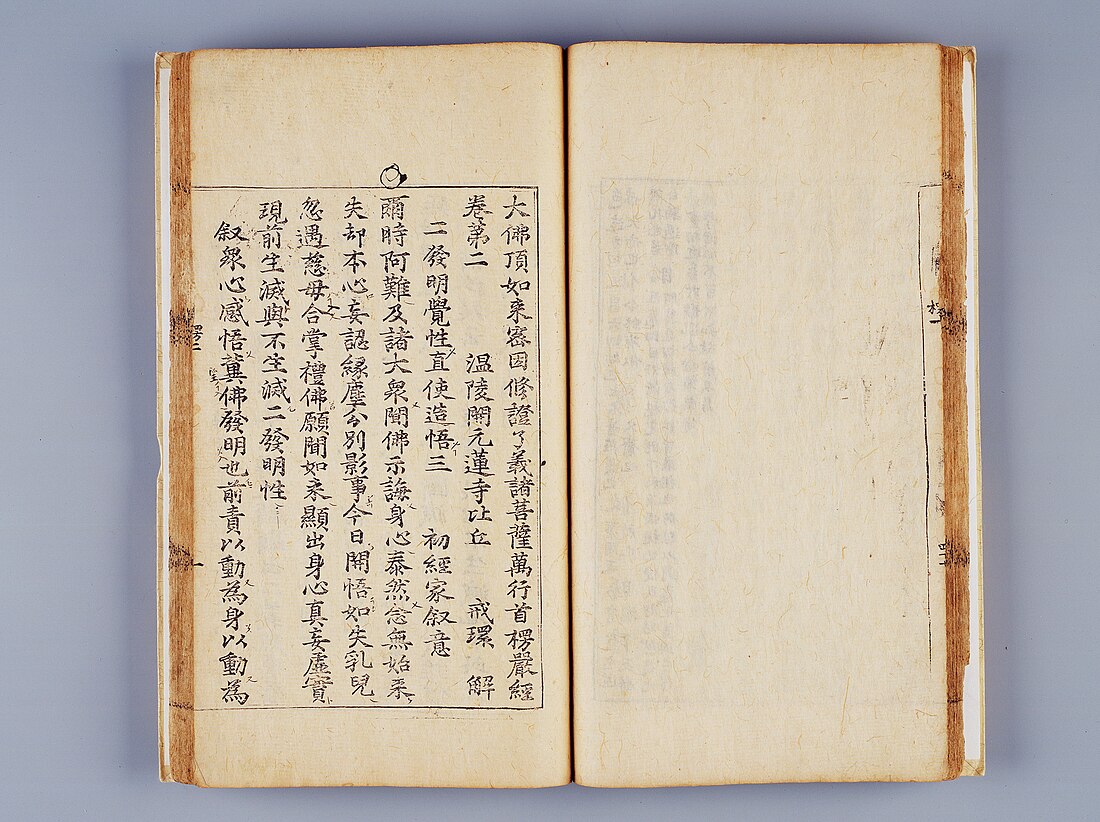

The complete title preserved in Chinese 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經 means:

The Sūtra on the Śūraṅgama Mantra that is spoken from above the Crown of the Great Buddha's Head and on the Hidden Basis of the Tathagata's Myriad Bodhisattva Practices that lead to their Verifications of Ultimate Truth.[9]

An alternate translation of the title reads:

The Sutra of the Foremost Shurangama at the Great Buddha's Summit Concerning the Tathagata's Secret Cause of Cultivation His Certification to the Complete Meaning and Bodhisattvas' Myriad Practices[10]

The title in different languages

A common translation of the sūtra's name in English is the "Heroic March sūtra" (as used e.g. by Matthew Kapstein, Norman Waddell, and Andy Ferguson), or the "scripture of the Heroic Progress" (as used e.g. by Thomas Cleary). The Sanskrit title preserved in the Chinese Tripitaka is Mahābuddhoṣṇīṣa-tathāgataguhyahetu-sākṣātkṛta-prasannārtha-sarvabodhisattvacaryā-śūraṅgama-sūtra, rendered by Hsuan Hua as "Sūtra of the Foremost Shurangama at the Great Buddha's Summit Concerning the Tathagata's Secret Cause of Cultivation, His Certification to Complete Meaning and All Bodhisattva's Myriad Practices".

The full title of the sūtra also appears as traditional Chinese: 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Dà Fódǐng Rúlái Mìyīn Xiūzhèng Liǎoyì Zhū Púsà Wànxíng Shǒuléngyán jīng; Korean: 대불정여래밀인수증료의제보살만행수릉엄경; Vietnamese: Đại Phật đỉnh Như Lai mật nhân tu chứng liễu nghĩa chư Bồ Tát vạn hạnh thủ-lăng-nghiêm kinh.

It is also known by abbreviated versions of the title such as traditional Chinese: 大佛頂首楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Dà Fódǐng Shǒuléngyán jīng; Korean: 대불정수릉엄경; Vietnamese: Đại Phật Đảnh Thủ-Lăng-Nghiêm Kinh or simply and more commonly traditional Chinese: 楞嚴經; ; pinyin: Léngyán jīng; Korean: 능엄경; Vietnamese: Lăng-Nghiêm Kinh.

Remove ads

Authorship

Summarize

Perspective

An original Sanskrit version of Śūraṅgama Sūtra is not known to be extant and the Indic provenance of the text is in question. A Sanskrit language palm leaf manuscript consisting of 226 leaves with 6 leaves missing which according to the introduction "contains the Śūraṅgama Sūtra" was discovered in a temple in China and now resides at Peng Xuefeng Memorial Museum. But scholars have not yet verified if this is the same text or some other sūtra (like the Śūraṅgama Samadhi Sūtra).[11]

The first catalogue that recorded the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was Zhisheng (Chinese: 智昇), a monk in Tang dynasty (618-907) China. Zhisheng said this book was brought back from Guangxi to Luoyang during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong. He gave two seemingly different accounts in two different books, both of which were published in 730 CE.

- According to the first account found in the Kaiyuan shijiao lu (Chinese: 開元釋教錄, lit: "The Kaiyuan Era Catalog of the Buddhist Tripitaka") the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in 713 CE by a Ven. Master Huai Di (Chinese: 懷迪) and an unnamed Indian monk. An official envoy to the south then brought the sūtra to the capital of Chang'an.[a][b][12]

- According to the second account, in his later book Xu gujin yijing tuji (續古今譯經圖記, lit: "Continuation to the History of the Translation of Buddhist Sūtras Mural Record"), the Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in May 705 CE by Śramaṇa Pāramiti from central India, who came to China and brought the text to the province of Guangzhou. The text was then polished and edited by Empress Wu Zetian's former minister, court regulator, and state censor Fang Yong (Chinese: 房融) of Qingho.[c] The translation was reviewed by Śramaṇa Meghaśikha from Oḍḍiyāna, and certified by Śramaṇa Huai-di (Chinese: 懷迪) of Nanlou Monastery (南樓寺) on Mount Luofu (羅浮山). Again, an official envoy to the south brought a copy of the sūtra to Chang'an.[d][12]

According to Jia Jinhua, who studied and cross-referred a number of external documents related to both accounts that Zhisheng gave, the two accounts do not conflict but rather complement each other, with the Kaiyuan shijiao lu written first and the Xu gujin yijing tuji written later once Zhisheng had acquired more details about the sūtra's translation and transmission.[12][13] According to Jia, the two accounts derive from two versions of the sūtra that were in circulation.[12]

Jia states that the first version brought from Guangzhou to Chang'an, which was included in the Kaiyuan catalogue and is extant in the Fangshan stone canon, listed the translators as Huaidi and an Indian monk and was the source for the account provided in the Kaiyuan shijiao lu.[12] He infers that the reason this version omitted Fang Rong’s name is because, at the time of the translation in 705, he was a disgraced and banished official in exile.[12] The reason for this exile was that on 20 February 705, Zhang Yizhi (張易之) and Zhang Changzong (張昌宗), two brothers who were Empress Wu’s favoured courtiers were killed in a coup, and Fang Rong was imprisoned for his close association with the Zhang brothers before being exiled to Gaozhou on 4 March.[12] Song dynasty (960-1279) records by the monk Zuxiu (祖琇) recorded that Fang Rong arrived in Guangzhou in the fourth month and was invited by the Prefect of Guangzhou to take part in translating the Śūraṃgama-sūtra.[12] The Tang court soon offered pardons to officials implicated in the affair involving the Zhang brothers, issuing amnesties and summoning officials back to court from the winter of 705 to the spring of 707, but Fang Rong unfortunately died in exile in Gaozhou.[12] Jia then infers that Zhisheng’s second account was based on a second version brought from Guangzhou to Chang'an by an official envoy at later time.[12] Jia reasons that, by then, the reason for Fang Rong’s exile had been pardoned, so there was no more taboo on signing his name on the sūtra, hence the second version lists in full the transmitter and translator of the sūtra, including Fang Rong as the transcriber and Huaidi as the verifier of the Sanskrit meanings.[12] This version is supported by detailed accounts of the same events and attributions from a commentary of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra by the monk Weique (惟慤), who was personally introduced to the sūtra by Fang Rong's family during a meal at their house.[12] Extracts of Weique's commentary with regards to the authorship of the sūtra is cited by the Japanese monk Genei (玄叡) in his work, the Daijō sanron daigi shō (大乘三論大義鈔, lit: "Digest of Major Doctrines of Mahāyāna Three Treatises"), and the details regarding how he was introduced to the sūtra is cited by the Song dynasty monk Zanning[zh] (贊寧) in his historical work, the Song gaoseng zhuan (宋高僧傳, lit: "Biographies of Eminent Monks of the Song dynasty").[12] This second version was then included in a later catalogue of Buddhist scriptures called the Zhenyuan catalogue, and is extant in various later Buddhist canons.[12]

Traditional views

In China, Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities, the sūtra is recognized as an authentic Buddhist scripture by all traditions of Chinese Buddhism such Chan, Pure Land, Tiantai and Huayan Buddhism.[12] Many eminent historical Chinese monastics, including the patriarchs of some traditions, have praised the sūtra's teachings, and more than one hundred commentaries have been written on it, over eighty of which are extant in the Buddhist canon.[12] The list of figures who have written commentaries on the sūtra include Zhongfeng Mingben, Yongming Yanshou (the Sixth Patriarch of the Chinese Pure Land tradition and the Third Patriarch of the Fayan tradition of Chan Buddhism), all of the Four Eminent Monks of the Wanli Era (consisting of Hanshan Deqing, Zibo Zhenke, Yunqi Zhuhong and Ouyi Zhixu, with Zhuhong being the Eighth Patriarch of the Chinese Pure Land tradition and Zhixu being the Ninth Patriarch of the Chinese Pure Land tradition as well as the Thirty-First Patriarch of the Tiantai lineage respectively), Youxi Chuandeng (the Thirtieth Patriarch of the Tiantai lineage), Taixu (a monk and activist trained in the Linji tradition of Chan Buddhism who was the mentor of several other prominent modern monastics) and Hsuan Hua (a major contributing figure in bringing Chinese Buddhism to the United States).[14] The sūtra has also always been classified as an authentic scripture in all Chinese-language Tripitakas, including the Taisho Tripitaka where it is placed in the Esoteric Sūtra category (密教部).[1] It remains a major subject of doctrinal study and practice in most contemporary Chinese Buddhist traditions. In addition, the sūtra in its entirety is chanted during certain rituals like the Shuilu Fahui ceremony and the mantra revealed within the sūtra is chanted during daily morning liturgical services in contemporary Chinese Buddhist practice.

The Qianlong Emperor and the Third Changkya Khutukhtu, the traditional head tulku of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Inner Mongolia, believed in the authenticity of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra.[15] They later translated the Śūraṅgama Sūtra into the Manchu language, Mongolian and Tibetan. (see translations)

In Japan, records state that the Śūraṃgama-sūtra was brought to Japan by the visiting monk Fushō (普照) in 754, which caused a debate over its authenticity. Emperor Shōmu gathered monastics from the Sanron and Hossō Buddhist traditions during the Tenpyō era (729–749) to examine the sūtra, and eventually reached the conclusion that it was authentic.[12] During the Hōki era (770–781 CE), Emperor Kōnin sent Master Tokusei (Hanyu Pinyin: Deqing; Japanese: 徳清), Master Kaimyō (Hanyu Pinyin: Jieming; Japanese: 戒明) and a group of monks to China, asking whether this book was a forgery or not. A Chinese upasaka or layperson named Faxiang (法詳) told the head monk of the Japanese monastic delegation, Master Tokusei, that this was forged by Fang Yong.[e][12] This once again raised doubts about the sūtra in Japan, but these were dismissed with another report from China that Emperor Daizong had the sūtra preached at the Tang court.[12] Later during the Hōki era, various monks gathered at Daian-ji and claimed the sūtra to be false, but Master Kaimyō, who had gone on the expedition to Tang-dynasty China earlier, refused to co-sign their claims and insisted that the sūtra was authentic. The sūtra remained influential in Japanese Buddhism as over seventy commentaries have been written on it, with the majority being from the Zen tradition.[16] In addition, eminent monastics such as Kōbō Daishi, the Eighth Patriarch and founder of the Shingon Buddhist tradition, and Dengyō Daishi, the founder of the Tendai Buddhist tradition, have also written works based on it. In contemporary Japanese Buddhist practice, the mantra revealed within the sūtra is still chanted across the three main Zen traditions of Rinzai, Sōtō and Ōbaku.

In favor of full Chinese composition

In China during the early modern era, the reformist Liang Qichao claimed that the sūtra is apocryphal, writing, "The real Buddhist scriptures would not say things like Surangama Sūtra, so we know the Surangama Sūtra is apocryphal.[f] In the same era, Lü Cheng (Chinese: 呂澂) wrote an essay to claim that the book is apocryphal, named "One hundred reasons about why Shurangama Sūtra is apocryphal" (Chinese: 楞嚴百偽).[6]

According to James Benn, the Japanese scholar Mochizuki Shinko's (1869–1948) Bukkyo kyoten seiritsu shiron "showed how many of the text's doctrinal elements may be traced to sources that already existed in China at the beginning of the eighth century, and he also described he early controversy surrounding the text in Japan."[6]

Charles Muller and Kogen Mizuno also hold that this sūtra is apocryphal (and is similar to other apocryphal Chinese sūtras). According to Muller, "even a brief glance" through these apocryphal works "by someone familiar with both indigenous sinitic philosophy and the Indian Mahāyāna textual corpus yields the recognition of themes, terms and concepts from indigenous traditions playing a dominant role in the text, to an extent which makes it obvious that they must have been written in East Asia."[4] He also notes that apocryphal works like the Śūraṅgama contain terms that were only used in East Asia:

...such as innate enlightenment (本覺 pen-chüeh) and actualized enlightenment (始覺 chih-chüeh) and other terms connected with the discourse of the tathāgatagarbha-ālayavijñāna problematik (the debate as to whether the human mind is, at its most fundamental level, pure or impure) appear in such number that the difference from the bona fide translations from Indic languages is obvious. Furthermore, the entire discourse of innate/actualized enlightenment and tathāgatagarbha-ālayavijñāna opposition can be seen as strongly reflecting a Chinese philosophical obsession dating back to at least the time of Mencius, when Mencius entered into debate with Kao-tzu on the original purity of the mind. The indigenous provenance of such texts is also indicated by their clear influence and borrowing from other current popular East Asian works, whether or not these other works were Indian or East Asian composition.[4]

James A. Benn notes that the Śūraṅgama also "shares some notable similarities with another scripture composed in China and dating to the same period", that is, the Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment.[6] Indeed, Benn states that "One might regard the Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment, which has only one fascicle, as opposed to the Śūraṅgama's ten, as a precis of the essential points of the Śūraṅgama."[6] Benn points out several passages which present uniquely Chinese understandings of animal life and natural phenomena that are without Indic precedent (such as the "Jelly fish with shrimp for eyes" and the "wasps, which take the larvae of other insects as their own") but that are found in earlier Chinese literature.[6]

James A. Benn also notes how the Śūraṅgama even borrows ideas that are mostly found in Taoist sources (such as the Baopuzi), such as the idea that there are ten types of "immortals" (仙 xiān) in a realm located between the deva realm and the human realm. The qualities of these immortals include common ideas found in Taoism, such as their "ingestion of metals and minerals" and the practice of "movement and stillness"(dongzhi, which is related to daoyin).[6] Benn argues that the Śūraṅgama's "taxonomy" of immortals was "clearly derived" from Taoist literature.[6] In a similar fashion, the Śūraṅgama's "ten types of demons" (鬼 gui), are also influenced by Taoist and Confucian sources.[6]

In favor of the sūtra being based on Indian originals

After the critiques of the Śūraṅgama from Lü Cheng and Liang Qichao, Shi Minsheng (釋愍生) wrote a book titled the Bianpo lengyan baiwei (辯破楞嚴百偽, lit: "Refutation of the One hundred reasons about why Śūraṅgama Sūtra is apocryphal"), establishing a rigorous response to them by criticizing both Lü and Liang for misunderstanding the Śūraṅgama Sūtra.[17][18][19] In Shi Minsheng's book, he listed one hundred arguments that directly corresponded to and countered Lü Cheng's list of one hundred critiques, cross-referencing and citing multiple other scriptures in the Buddhist canon to undermine each of Lü's critiques by demonstrating that they were based on misinterpretations of the text or lack of understanding regarding Buddhist doctrines.[17][18][19]

In his examination of the authenticity of the Surangama Sūtra as well as arguments presented by past academics on the issue, Jia Jinhua notes that the presence of Chinese or Taoist elements in the text that have been noted by some academics such as those mentioned by James A. Benn, "comprise only a tiny ratio of the whole sūtra, and are mostly sporadic terms and allusions that do not form significant ideas of indigenous Chinese origin; thus, they do not necessarily indicate a Chinese origin for the sūtra. Rather, they can be seen as translative substitutions of parallel Sanskrit elements applied by the translators."[12] In other words, they represent the translators' method of finding functional native Chinese equivalents that closely resemble and parallel the original concepts in the Sanskrit source.[12] Indeed, he further notes that "Chinese terms and allusions appear more or less in almost all Buddhist scriptures of Chinese translation. For example, Daoist “philosophical” terms such as Dao 道, wu 無, wuwei 無為, and so forth appear everywhere in authentic translated sūtras. While Daoist “religious” terms are less commonly seen, several sūtras translated during Empress Wu’s reign do contain this kind of terminology."[12]

Ron Epstein gives an overview of the arguments for Indian or Chinese origin, and concludes:[20]

Preliminary analysis of the internal evidence then indicates that the Sutra is probably a compilation of Indic materials that may have had a long literary history. It should be noted though, that for a compilation, which is also how the Sutra is treated by some traditional commentators, the Sutra has an intricate beauty of structure that is not particularly Chinese and which shines through and can clearly be distinguished from the Classical Chinese syntax, on which attention has usually been centered. Thus one of the difficulties with the theory that the Sutra is apocryphal is that it would be difficult to find an author who could plausibly be held accountable for both structure and language and who would also be familiar with the doctrinal intricacies that the Sutra presents. Therefore, it seems likely that the origin of the great bulk of material in the Sutra is Indic, though it is obvious that the text was edited in China. However, a great deal of further, systematic research will be necessary to bring to light all the details of the text's rather complicated construction.

A number of scholars have associated the Śūraṅgama Sūtra with the Buddhist tradition at Nālandā.[21][22]

Epstein thinks that certain passages in the sūtra do show Chinese influence, such as the section on the Taoist immortals, but he thinks that this "could easily represent an adaptive Chinese translation of Buddhist tantric ideas. The whole area of the doctrinal relationship between the Taoist nei-tan, or so-called "inner alchemy", and early Buddhist tantra is a murky one, and until we know more about both, the issue probably cannot be resolved adequately."[20] Epstein further writes regarding uniquely Chinese influences found in the text: "As to things Chinese, there are various short references to them scattered throughout the text, but, just as well as indicating the work's Chinese origin, they also could be an indication of a translation style of substitution of parallel items, which would fit right in with the highly literary Chinese phraseology."[20]

In arguing for an Indic origin, Epstein gives three main reasons:

- He argues many Sanskrit terms which appear in the text, "including some not often found in other Chinese translations. Moreover, the transliteration system does not seem to follow that of other works."[20]

- Epstein also notes that the general doctrinal position of the sūtra (tantric tathagatagarbha teachings) does indeed correspond to what is known about the Buddhist teachings at Nālandā during this period.[20]

- Large sections "definitely seem to contain Indic materials. Some passages could conceivably have been constructed from texts already translated into Chinese, although given the bulk and complexity of the material, to account for much of the text in that way would mean that the task of authorship would have had to have been an enormous one. About other portions of the work, such as the bodhimanda and mantra, there can be no doubt about their direct Indic origin."[20]

Similarly, Rounds argues for an Indic source by pointing out "two indisputably Indian elements" in the sūtra: the text's reliance on the Buddhist science of reasoning (hetuvidya) and the Śūraṅgama mantra.[23]

Remove ads

Non-Chinese Translations

Summarize

Perspective

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated into Tibetan probably during the late eighth to early ninth century.[24][25][26] However possibly because of the persecution of Buddhism during King Langdarma's reign (ca. 840-841), only a portion of Scroll 9 and Scroll 10 of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra are preserved in the surviving two ancient texts.[27][28][29] Buton Rinchen Drub Rinpoche mentioned that one of the two texts was probably translated from Chinese; thereby suggesting the second text may have possibly been translated from another language.[30]

The entire Śūraṅgama Sūtra was translated in 1763 from Han Chinese into the Manchu language, Mongolian and Tibetan languages and compiled into a four language set at the command of the Qianlong Emperor.[31][32] The third Changkya Khutukhtu Rölpé Dorjé or 若必多吉 or Lalitavajra (1716–1786) convinced the Qianlong Emperor to engage in the translation.[33] The third Changkya Khutukhtu supervised (and verified) with the help of Fu Nai the translation of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra.[34][35] The complete translation of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra into Tibetan is found in a supplement to the Narthang Kangyur.[36][37]

English translations

There are a few English translations:

- The Surangama Sūtra, published in A Buddhist Bible, translated by Dwight Goddard and Bhikshu Wai-tao.

- Charles Luk, 1967, Shurangama Sūtra

- The Shurangama Sūtra with commentary by Master Hsuan Hua. Volumes 1 to 8. Buddhist Translation Society, 2nd edition (October 2003).

- Buddhist Text Translation Society (2009). The Śūraṅgama Sūtra, With Excerpts from the Commentary by the Venerable Master Hsüan Hua, A New Translation, p. 267. Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, 4951 Bodhi Way, Ukiah, California 95482 (707) 462–0939, bttsonline.org.

Teachings

Summarize

Perspective

Doctrinal orientation

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra contains teachings from Yogācāra, Buddha-nature, and Vajrayana.[20][38] It makes use of Buddhist logic with its methods of syllogism and the catuṣkoṭi "fourfold negation" first popularized by Nāgārjuna.[39]

Main themes

One of the main themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is how knowledge of the Buddha's teaching (Dharma) is worthless unless it is coupled with the power of samādhi (meditative absorption), as well as the importance of moral precepts as a foundation for the Buddhist practice.[20] Also stressed is the theme of how one effectively combats delusions and demonic influences that may arise during meditation.[20][g]

According to Ron Epstein, a key theme of the sūtra is the "two types of mind", furthermore, "also contained in the work are a discussion of meditational methodology in terms of the importance of picking the proper faculty (indriya) as a vehicle for meditation, instructions for the construction of a tantric bodhimanda, a long mantra, a description of fifty-seven Bodhisattva stages, a description of the karmic relationship among the destinies (gati), or paths of rebirth, and an enumeration of fifty demonic states encountered on the path."[20]

Ron Epstein and David Rounds have suggested that the major themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra reflect the strains upon Indian Buddhism during the time of its creation.[41] They cite the resurgence of non-Buddhist religions, and the crumbling social supports for monastic Buddhist institutions. This era also saw the emergence of Hindu tantrism and the beginnings of Esoteric Buddhism and the siddha traditions.[41] They propose that moral challenges and general confusion about Buddhism are said to have then given rise to the themes of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, such as clear understanding of principles, moral discipline, essential Buddhist cosmology, development of samādhi, and how to avoid falling into various delusions in meditation.[41]

Two types of mind

A key theme found in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is the distinction between the true mind and the discriminating mind.[23] The discriminating worldly mind is the ordinary quotidian mind that becomes entangled in rebirth, thinking, change and illusion. But, according to the Śūraṅgama, there is also "an everlasting true mind, which is our real nature, and which is the state of the Buddha."[23] According to the Śūraṅgama, the worldly mind "is the mind that is the basis of death and rebirth and that has continued for the entirety of time...dependent upon perceived objects."[23]

This worldly mind is mistaken by sentient beings as being their true nature. Meanwhile, the "pure enlightened mind" is the underlying nature of all dharmas (phenomena). It is the ultimate reality which is also enlightenment, which has no beginning. It is the original and pure essence of nirvana.[23] The true awakened mind is an unchanging awareness that remains still and independent of all sense objects, even while the discriminating mind changes.[23] The pure mind then is the essential nature of awareness, not the ordinary awareness which is distorted and diseased.[23]

This theme of the everlasting true mind which is contrasted with the samsaric mind is also a common theme of the Mahayana Awakening of Faith treatise.[4]

Buddha-nature

The "everlasting true mind" is associated with the Mahayana teaching of tathāgatagarbha or buddha-nature. Rounds and Epstein explain the Śūraṅgama's conception of the tathāgatagarbha, the "Matrix of the Thus Come One", as follows:[42]

Fundamentally, everything that comes and goes, that comes into being and ceases to be, is within the true nature of the Matrix of the Thus-Come One, which is the wondrous, everlasting understanding — the unmoving, all-pervading, wondrous suchness of reality.

[The Buddha] shows one by one that each of the elements of the physical world and each of the elements of our sensory apparatus is, fundamentally, an illusion. But at the same time, these illusory entities and experiences arise out of what is real. That matrix from which all is produced is the Matrix of the Thus-Come One. It is identical to our own true mind and identical as well to the fundamental nature of the universe and to the mind of all Buddhas.

Thus, according to the Śūraṅgama Sūtra the "buddha-womb" or "buddha-essence" is source of mind and world.[23] This buddha nature is originally pure enlightenment, however, due to the deluded development of a subject-object separation, the whole world of birth and death arises.[23]

Meditation practices

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra teaches about the Śūraṅgama Samādhi (the "meditative absorption of the heroic march"), which is associated with complete enlightenment and Buddhahood. This samādhi is also featured extensively in the Śūraṅgama Samādhi Sūtra. It is equally praised in the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, where it is explained by the Buddha that this samādhi is the essence of the nature of the Buddha and is indeed the "mother of all Buddhas."[43] The Buddha also comments that the Śūraṅgama Samādhi additionally goes under several other names, specifically Prajñāpāramitā ("Perfection of Wisdom"), the Vajra Samādhi, the Siṃhanāda Samādhi ("Lion's Roar Samādhi"), and the Buddha-svabhāva.[43]

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra contains various explanations of specific meditation practices which help one cultivate samadhi, including a famous passage in which twenty five sages discuss twenty five methods of practice. The main intent of these various methods is to detach one's awareness of all sense objects and to direct awareness inward, to the fundamental true nature. This leads to the experience of the disappearance of everything and finally to illumination.[23]

The most well known part of this passage is the meditation taught by bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the last of these sages to teach. Avalokiteshvara describes their method as follows:[44]

I began with a practice based on the enlightened nature of hearing. First I redirected my hearing inward in order to enter the current of the sages. Then external sounds disappeared. With the direction of my hearing reversed and with sounds stilled, both sounds and silence ceased to arise. So it was that, as I gradually progressed, what I heard and my awareness of what I heard came to an end. Even when that state of mind in which everything had come to an end disappeared, I did not rest. My awareness and the objects of my awareness were emptied, and when that process of emptying my awareness was wholly complete, then even that emptying and what had been emptied vanished. Coming into being and ceasing to be themselves ceased to be. Then the ultimate stillness was revealed. All of a sudden I transcended the worlds of ordinary beings, and I also transcended the worlds of beings who have transcended the ordinary worlds. Everything in the ten directions was fully illuminated, and I gained two remarkable powers. First, my mind ascended to unite with the fundamental, wondrous, enlightened mind of all Buddhas in all ten directions, and my power of compassion became the same as theirs. Second, my mind descended to unite with all beings of the six destinies in all ten directions such that I felt their sorrows and their prayerful yearnings as my own.

The other section of the sūtra which is influential in Chinese Buddhism is the passage which details the meditation method of Mahasthamaprapta Bodhisattva. This section is considered to be a major text of Chinese Pure Land Buddhism, since it discusses the practice of nianfo (recollection of the Buddha Amitabha).[45][5][46] This passage states:

beings who are always mindful of the Buddha, always thinking of the Buddha, are certain to see the Buddha now or in the future. They will never be far from Buddhas, and their minds will awaken by themselves without any special effort. Such people may be said to be adorned with fragrance and light, just as people who have been in the presence of incense will naturally smell sweet. The basis of my practice was mindfulness of the Buddha. I became patient with the state of mind in which no mental objects arise. Now when people of this world are mindful of the Buddha, I act as their guide to lead them to the Pure Land. The Buddha has asked us how we broke through to enlightenment. In order to enter samādhi, I chose no other method than to gather in the six faculties while continuously maintaining a pure mindfulness of the Buddha. This is the best method.[47]

Ethics and traditional practices

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra also focuses on the necessity of keeping traditional ethical precepts, especially the five precepts and the monastic vinaya.[48][49][50] These precepts are said to be the basis to samadhi which in turn leads to wisdom.[51][52] The Buddha describes the precepts as clear and unalterable instruction on purity which transverse time and place. If one breaks them (by killing, stealing, lying etc.) one will never reach enlightenment, no matter how much one meditates.[53][23]

Indeed, according to the Śūraṅgama:

No matter how much you may practice samādhi in order to transcend the stress of entanglement with perceived objects, you will never transcend that stress until you have freed yourself from thoughts of killing. Even very intelligent people who can enter samādhi while practicing meditation in stillness are certain to fall into the realm of ghosts and spirits upon their rebirth if they have not renounced all killing.[54]

Similarly, the sūtra also claims that unless one frees oneself from sensual desire, sexual activity, meat eating (which it associated with killing), stealing or lying, one will not reach enlightenment.[23][55] According to the Śūraṅgama, even though one may have some wisdom and meditative absorption, one is certain to enter bad rebirths, even the hells, if one does not cease lust, killing, stealing and making false claims.[55]

The Śūraṅgama also warns against heterodox teachers who practice meditation without being properly prepared and then fall under the influence of demons. These teachers then begin to spout heterodoxies, such as the idea that practitioners should stop revering stupas and temples, wishing to destroy sūtras and Buddha statues and engaging in sex while saying that "the male and female organs are the true abodes of bodhi and nirvana".[6] James A. Benn notes that the first teaching may be a reference to certain radical Chan masters of the time, while the second one may refer to certain esoteric Buddhist practices which made use of ritual sex.[6]

Diet, lifestyle and ascetic practice

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra argues for strict dietary rules, including vegetarianism and the avoidance of the five pungent roots (radish, leek, onion, garlic, asafoetida).[6] The sūtra argues that these dietary choices "drive away bodhisattvas, gods, and xian [immortals], who protect the practitioner in this life, and attracts instead hungry ghosts."[6] The sūtra also states that eating meat can have dire consequences:

You should know that those who eat meat, although their minds maybe opened and realize a semblance of samadhi, will become great raksasas (demons). When that retribution is over, they will sink back into the bitter ocean of samsara and will not be able to be disciples of the Buddha.[6]

The Śūraṅgama goes even further with its ascetic injunctions, recommending the avoidance of animal products such as silk, leather, furs, milk, cream, and butter and arguing that this abstention can be a cause of enlightenment:[6]

Bodhisattvas and pure monks walking on country paths will not even tread on living grasses, much less uproot them. How then can it be compassionate to gorge on other beings' blood and flesh? Monks who will not wear silks from the East, whether coarse or fine; who will not wear shoes or boots of leather, nor furs, nor birds' down from our own country; and who will not consume milk, curds, or ghee, have truly freed themselves from the world. When they have paid their debts from previous lives, they will roam no longer through the three realms. "Why? To wear parts of a being's body is to involve one's karma with that being, just as people have become bound to this earth by eating vegetables and grains. I can affirm that a person who neither eats the flesh of other beings nor wears any part of the bodies of other beings, nor even thinks of eating or wearing these things, is a person who will gain liberation.[56]

The sūtra also teaches the practice of the burning of the body as an offering to the Buddhas.[6]

The White Parasol Crown Dhāraṇī

In addition to the sūtra's doctrinal content, it also contains a long dhāraṇī (chant, incantation) which is known in Chinese as the Léngyán Zhòu (楞嚴咒), or Śūraṅgama Mantra. It is well-known and popularly chanted in East Asian Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the dhāraṇī is known as the Sitātapatra Uṣṇīṣa Dhāraṇī (Ch. 大白傘蓋陀羅尼). This is sometimes simplified in English to White Canopy Dhāraṇī or White Parasol Dhāraṇī. In Tibetan traditions, the English is instead sometimes rendered as the "White Umbrella Mantra." The dhāraṇī is extant in three other translations found in the Chinese Buddhist canon[h], and is also preserved in Sanskrit and Tibetan.

This dhāraṇī is often seen as having magical apotropaic powers, as it is associated with the deity Sitātapatra, a protector against supernatural dangers and evil beings.[57] The Śūraṅgama Sūtra also states that the dhāraṇī can be used as an expedient means to enter into the Śūraṅgama samadhi.[23] According to Rounds, the sūtra also "gives precise instructions on the construction and consecration of a sacred space in which a practitioner can properly focus on recitation of the mantra."[23]

The Śūraṅgama Mantra is widely recited in China, Korea and Vietnam by Mahayana monastics on a daily basis and by some laypersons as part of the Morning Recitation Liturgy.[2][3] The mantra is also recited by some Japanese Buddhist sects.

Realms of rebirth, bodhisattva stages and Demons

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra also contains various explanations of Buddhist cosmology and soteriology. The sūtra outlines various levels of enlightenment, the fifty-five bodhisattva stages. It also contains explanations of the horrible sufferings that are experienced in the hells (narakas) as well as explanations of the other realms of rebirth.[23]

Another theme found in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is that of various Māras (demonic beings) which are manifestations of the five skandhas (aggregates).[7] In its section on the fifty skandha-māras, each of the five skandhas has ten skandha-māras associated with it, and each skandha-māra is described in detail as a deviation from correct samādhi. These skandha-māras are also known as the "fifty skandha demons" in some English-language publications. Epstein introduces the fifty skandha-māras section as follows:[58]

For each state a description is given of the mental phenomena experienced by the practitioner, the causes of the phenomena and the difficulties which arise from attachment to the phenomena and misinterpretation of them. In essence what is presented is both a unique method of cataloguing and classifying spiritual experience and indication of causal factors involved in the experience of the phenomena. Although the fifty states presented are by no means exhaustive, the approach taken has the potential of offering a framework for the classification of all spiritual experience, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist.

Remove ads

Influence

Summarize

Perspective

Mainland East Asia

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra has been widely studied and commented on in Chinese Buddhism. Ron Epstein has "found reference to 127 Chinese commentaries on the Sūtra, quite a few for such a lengthy work, including 59 in the Ming dynasty alone, when it was especially popular".[20]

Two principal factors underpinned its appeal. First, the text presents Buddha-nature through the concept of xin xing (心性), or mind-nature, aligning with the interpretive framework common to most Chinese Buddhist traditions. Second, its doctrinal content is thoroughly Mahāyāna, resonating with the dominant philosophical orientation of Chinese Buddhism since the Tang. Once the sūtra appeared during the Tang, it was swiftly integrated into various schools, especially the Chan tradition. Chan patriarch Baotang Wuzhu (保唐無住, 714–774), founder of the Baotang lineage, was the first to extensively cite the Śūraṃgama Sūtra to support Chan teachings. Prominent later Chan figures such as Guishan (溈山), Yangshan (仰山), and Fayan (法眼) were also deeply familiar with the text. The earliest known commentary, by Weique (惟愨), was produced in 766.[59]

In the Tang and Song dynasties influential figures like Guifeng Zongmi (圭峰宗密, 780–841) and Yongming Yanshou (永明延壽, 904–975) helped advance the sūtra's prestige. Zongmi, who bridged the Huayan and Chan schools, frequently cited it in his interpretation of the Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment and considered it a supreme expression of doctrine, emblematic of the unity of Chan and scriptural teaching. Similarly, Yanshou made extensive use of the sūtra in his major treatise, Zongjing lu (宗鏡錄), to reinforce the same theme.[59] Exegesis on the Śūraṃgama Sūtra proliferated during the Song, especially among thinkers affiliated with the Huayan, Tiantai, and Chan traditions. Changshui Zixuan (長水子璿, 965–1038), who revitalized the Huayan school, earned the epithet "Grand Master of the Śūraṃgama" due to his influential commentary, Lengyan yishu (楞嚴義疏). His disciple, Jinshui Jingyuan (晉水淨源, 1011–1088), composed the first ritual manual based on the sūtra, Shoulengyan tanchang xiuzheng yi (首楞嚴壇場修證儀).[59] Tiantai tradition also revered the sūtra. Key Tiantai masters of the Song like Siming Zhili (四明知禮, 960–1028) and Ciyun Zunshi (慈雲遵式, 964–1032) drew upon the Śūraṃgama Sūtra to support their positions. Commentaries by Gushan Zhiyuan (孤山智圓, 976–1022) and Renyue Jingjue (仁岳淨覺, 992–1064) became especially influential.[59]

In the Song era Chan school, the sūtra was revered as “the marrow of Chan” and became a central text. Chan monks used its content to support and deepen the integration of meditative and doctrinal practice. Masters such as Dahui Zonggao (大慧宗杲, 1089–1163) and Hongzhi Zhengjue (宏智正覺, 1091–1157) interpreted its teaching on the “ear-organ entry” as a model for Chan realization.[59] During the Song Dynasty the sūtra was used in a ritual called the Śūraṅgama assembly which "was held semi-annually during monastic retreats, and there the participants chanted the long magical spell (dharani) contained in the sūtra. The dharani was also recited at memorial services for Chan abbots and patriarchs."[6] The sūtra is cited in various Chan Buddhist texts, like the Blue Cliff Record (case 94).[60][i] The Śūraṅgama Sūtra also influenced the work of several Song intellectuals, like Su Shi (1037–1101) and Su Zhe (1039–1112).[6]

Beyond Buddhism, the sūtra also began to influence Daoist and Confucian intellectuals in the Song. It was a preferred text among literati with Buddhist interests. As noted by official Chen Guan (陳瓘, 1042–1106), lay scholars often limited their Buddhist reading to a few key works, including the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. Distinguished figures such as Su Shi (蘇軾), Su Che (蘇轍), Wang Anshi (王安石), Zhang Shangying (張商英), and Huang Tingjian (黃庭堅) were all familiar with it. Commentaries by Wang and Zhang were particularly esteemed by monastic readers.[59]

The sūtra retained its prominence during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Chan masters Zhongfeng Mingben (中峰明本, 1263–1323) and his disciple Tianru Weize (天如惟則, 1284–1354) continued to promote its study. Weize’s commentary, Lengyan huijie (楞嚴會解), became the most authoritative exegetical work on the sūtra for the next two centuries. He asserted that no other scripture equaled the Śūraṃgama Sūtra in elucidating mind-nature, making it essential for Chan practice. Although Huayan and Tiantai were in decline during the Yuan, figures like Biefeng Datong (別峰大同, 1289–1370) and Yuanmeng Yunze (雲夢允澤, 1232–1297) sought to revitalize their respective schools through engagement with the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. Even Pure Land master Pudu (普度, d. 1330) drew on the sūtra to bolster his interpretation of Pure Land practice.[59]

The Ming dynasty saw the Śūraṅgama Sūtra at the height of its popularity in China.[62] By the mid-Ming period, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra retained significant influence, particularly among eminent monks and the educated elite. During this time, the Huayan monk Huijin 慧進 (1355–1436) was invited to lecture on the Śūraṅgama Sūtra in the imperial capital, drawing audiences exceeding ten thousand.[63] During the late Ming period, the Śūraṃgama Sūtra reached a peak in its influence and popularity among both Buddhist circles and the broader intellectual elite. Over the seventy-year span of the late Ming, more commentarial works on the Śūraṃgama Sūtra were produced than in any other historical period. The Qing-era monastic scholar Tongli (通理, 1701–1782) recorded at least sixty-eight known commentaries between the sūtra’s appearance in the Tang and his own time, with thirty of these composed during the late Ming alone—surpassing the twenty produced in the Song. A more comprehensive modern count confirms this trend: out of 135 commentaries written from the Tang through the Qing, sixty originated in the Ming, with over fifty of those concentrated in the late Ming. The range of authors (including Buddhists, Confucians, and Daoists) indicates the text’s wide dissemination and popularity among the literati.[59]

The continued relevance of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra during the Ming is largely attributable to its sophisticated exposition of mind-nature (心性), a theme that resonated across the Chinese intellectual landscape in the Ming. As a tradition of foreign origin, Buddhism had long positioned itself in dialogue with native Chinese philosophies. It was only in the Ming dynasty, however, that the convergence of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism achieved a degree of philosophical integration around the principle that mind-nature is truth. This development reflected a broader trend of doctrinal synthesis among the three teachings.[63] One key figure in this transformation was the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming 王陽明 (1472–1529), who reoriented Confucian metaphysics by emphasizing the concept of innate knowing (良知 liang zhi). In his system, the mind supplanted Heavenly Principle (天理) as the foundational reality, thereby identifying the mind as the source and substance of all phenomena. Wang’s system gained wide acceptance in Confucian circles and served to dissolve longstanding boundaries between the three traditions. This philosophical convergence catalyzed the late Ming movement known as "Three Teachings in One" (三教合一), which advocated the fundamental compatibility of Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism.[63]

Moreover, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra became a tool through which Buddhists articulated the superiority of their doctrine over that of the other traditions. For example, one promoter of the sūtra, the eminent monk Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲袾宏), while acknowledging that the three teachings express a common principle with varying degrees of profundity, asserted that the teachings of Confucian and Daoist sages failed to attain the depth of insight found in the sūtra’s presentation of the Way (dao).[63] As such, this influential monk held that would should begin one's studies with this sūtra: "The Śūraṃgama Sūtra has the best order [in discussing Buddhist teaching], one should read it first."[64] He also used the sūtra to defend his promotion of the dual practice of Chan and Pure Land, as well as to argue for the unity of all Buddhist teachings (including Esoteric Buddhism and Vinaya).[64]

In this period, scholarly engagement with the Śūraṃgama Sūtra played a significant role in the broader Buddhist revival. Other influential figures who wrote commentaries on the Śūraṃgama were Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清, who is said to have attained enlightenment through the sūtra), Zibo Zhenke (紫栢真可), Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭), Jiaoguang Zhenjian (交光真鑑) and Youxi Chuandeng (幽溪傳燈).[65] Chuandeng relied on the sūtra to revive the Tiantai school and wrote various commentaries on it.[66][20] Hanshan Deqing captured the spirit of the Ming era's attachment to the sūtra when he wrote:

[The Śūraṃgama Sūtra] has thorough insight into the origin of the one-mind and includes all the dharmas to the utmost extent. No scripture surpasses the extensiveness and completion of this sūtra.[67]

The sūtra continued to remain popular during the succeeding Qing dynasty (1644-1912) through to the modern era. For instance, the eminent monk, Venerable Yinguang, who is the Thirteenth Patriarch of the Chinese Pure Land tradition, promoted the "Chapter of Bodhisattva Dashizhi’s (Mahāsthāmaprāpta) Perfect Realisation on Nianfo Samādhi" from the sūtra as the fifth Pure Land sūtra, together with the Amitābha Sūtra, the Amitāyus Sūtra, the Amitāyus Contemplation Sūtra and "The Practices and Vow of the Bodhisattva Puxian (Samantabhadra)" (which constitutes the last chapter of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra). Commentaries also continued to be produced by various eminent monks during this period. For instance, during the early Qing dynasty, the eminent monk Boting Xufa (伯亭續法), who was a dharma descendent of Yunqi Zhuhong and who specialized in the Huayan tradition, wrote a commentary titled the Shou lengyan jing guanding shu (首楞嚴經灌頂疏) which has remained influential in contemporary times.[68] As another example, the eminent Chan master Venerable Xuyun, who was a mentor to many influential Buddhist teachers, wrote a commentary on the Śūraṅgama Sūtra which was unfortunately lost in 1951 during the horrific persecution of monks under the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries. Other examples of influential commentaries written during this period are the Dafoding lengyan jing jiangji (大佛頂首楞嚴經講記) by Venerable Hairen (海仁), the similarly titled Dafoding lengyan jing jiangji (大佛頂首楞嚴經講記) by Venerable Tanxu (倓虛), the Dafoding lengyan jing miaoxin shu (大佛頂首楞嚴經妙心疏) by Venerable Shoupei (守培) and the Dafoding lengyan jing jiangyi (大佛頂首楞嚴經講義) by Venerable Yuanying (圓瑛).

Venerable Hsuan Hua, who was among the first to teach Chinese Buddhism in America, was another major modern proponent of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. The sūtra along with his commentary on it was translated and published in English in 2003 by the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, which he founded. According to Hsuan Hua:

In Buddhism all the sutras are very important, but the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is most important. Wherever the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is, the Proper Dharma abides in the world. When the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is gone, the Dharma Ending Age is before one's eyes. (In the Extinction of the Dharma Sutra it says that in the Dharma Ending Age, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra will become extinct first. Then gradually the other sutras will also become extinct.)[69] The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is the true body of the Buddha; the śarīra (relics) of the Buddha; the stūpa of the Buddha. All Buddhists must support with their utmost strength The Śūraṅgama Sūtra [70]

It remains a major subject of doctrinal study and practice in most contemporary Chinese Buddhist traditions, with many popular modern eminent monastics in China, Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities such as Sheng-yen (聖嚴), Chin Kung (淨空), Chengguan (成觀), Huilü (慧律) and Jingjie (淨界) having written commentaries on the sūtra or lectured on its teachings. The sūtra in its entirety is usually chanted in rituals such as the Shuilu Fahui ceremony, and the Śūraṅgama mantra revealed in the sūtra is typically chanted as part of the daily morning liturgical session in most Chinese Buddhist monasteries.

Korea

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra was also important in Korean Buddhism. It became a required text for Korea's monastic examination system during the Joseon period.[6] The Śūraṅgama remains one of the most influential sources in the advanced curriculum of Korean Sŏn monasteries, along with the Awakening of Faith and the Vajrasamadhi sūtra.[4]

Japan

The Japanese Zen Buddhist Dōgen held that the sūtra was not an authentic Indian text.[20] But he also drew on the text, commenting on the Śūraṅgama verse "when someone gives rise to Truth by returning to the Source, the whole of space in all ten quarters falls away and vanishes" as follows:

This verse has been cited by various Buddhas and Ancestors alike. Up to this very day, this verse is truly the Bones and Marrow of the Buddhas and Ancestors. It is the very Eye of the Buddhas and Ancestors. As to my intention in saying so, there are those who say that the ten-fascicle Shurangama Scripture is a spurious scripture, whereas others say that it is a genuine Scripture: both views have persisted from long in the past down to our very day [...] Even were the Scripture a spurious one, if [Ancestors] continue to offer its turning, then it is a genuine Scripture of the Buddhas and Ancestors, as well as the Dharma Wheel intimately associated with Them.[71]

The sūtra was influential in Japanese Buddhism as over seventy historical commentaries have been written on it, with the majority being from the Zen tradition.[16] In addition, eminent monastics such as Kōbō Daishi, the Eighth Patriarch and founder of the Shingon Buddhist tradition, and Dengyō Daishi, the founder of the Tendai Buddhist tradition, have also written works based on it. In contemporary Japanese Buddhist practice, the Śūraṅgama mantra revealed in the sūtra is still chanted across the three main Zen traditions of Rinzai, Sōtō and Ōbaku.

Remove ads

Notes

Summarize

Perspective

Note: Several notes are Chinese, due to the international character of Wikipedia. Help in translation is welcome.

- The Kaiyuan Era Catalog of the Buddhist Tripitaka said, "Venerable Huai Di (Chinese: 懷迪), a native of Xún zhōu (循州) [located in parts of today's Guangdong Province], lived in Nanlou Monastery (南樓寺) on Mount Luofu (羅浮山). Mount Luofu is where many ṛsi lived and visited. Ven. Huai Di studied Buddhist sutras and sastras for a long time, and achieved profound erudition. He was also proficient in a wide range of knowledge. Here close to the coast, there are many Indian monks who come here. Ven. Huai Di learned how to say and read their language with them. When Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra was translated to Chinese, Bodhiruci invited Huai Di to verify the translation. After the translation was finished, he returned to his hometown. Once he came to Guangzhou, he met a monk, whose name was unrecorded, from India with a Sanskrit book. He asked Huai Di to translate this book, a total of ten volumes, which was Shurangama Sutra. Ven. Huai Di wrote this book and modified the wording. After the book was translated, the monk left, and no one knows where he went. An official went to southern China, bringing this book back, so it became known here."[I]

- In 706 CE, Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra began translation. HuaiDi was invited to Luoyang. The translation was finished in 713 CE. HuaiDi then went back to his hometown. The Shurangama Sutra was translated after 713 CE.

- The mention of Fang Yong poses a chronological problem. According to the Old Book of Tang Fang Yong was put in prison in January 705 CE because he was involved in a court struggle. He was then exiled from Luoyang to Guangxi Qinzhou in February, where he died.[II] If the book was translated at 705 CE, the cooperation of Fang Yong might be doubtful. If the text was translated in 713 CE, Fang Yong had no chance to aid in the translation of the text, since he died in 705

- The Continuation to the History of the Translation of Buddhist Sutras Mural Record said, "Śramaṇa Pāramiti, which is means Quantum, came from Central India. He travel, missionary, arrived china. He stayed at Guangxiao Temple in Guangxi. Because he was very knowledgeable, so many people came to visit him. To help people, so he determined not to keep secret. in May 23 705 CE, He recited a Tantras, which is The Sūtra on the Śūraṅgama Mantra Spoken from Above the Crown of the Great Buddha's Head, and on the Hidden Basis of the Tathagata's Myriad Bodhisattva Practices Leading to Their Verification of the Ultimate Truth. Śramaṇa Meghaśikha from Oḍḍiyāna translated it to Chinese. Fang Yong(Chinese: 房融) of Qingho, the former minister, court regulator, and state censor, wrote it down. Śramaṇa Huai-di (Chinese: 懷迪) of Nanlou Monastery (南樓寺) on Mount Luofu (羅浮山) verify it. After teach it all, he came back to his country. An official went to southern China, bringing this book back, so we see it here. "[III]

- in-depth meaning of Three Treatise school said, "(Emperor Kōnin) sent Master Tokusei (Hanyu Pinyin: Deqing; Japanese: 徳清) and other monks to Tang China to find the answer. Upasaka Fa-Xiang (Chinese: 法詳) told Master Tokusei (Hanyu Pinyin: Deqing; Japanese: 徳清) : This Shurangama Sutra is forged by Fang Yong, not a real Buddhavacana. But Zhi-sheng know nothing about it, so he make a mistake to list this book at The Kaiyuan Era Catalog of the Buddhist Tripitaka."[IV]

- Liang Qichao, the authenticity of Ancient books and their year, "The real Buddhist scriptures would not say things like Śūraṅgama Sūtra, so we know the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is a Apocrypha."[V][citation needed]

- Taishō Tripiṭaka 944, 976, and 977

- In the Blue Cliff Record: "In the Surangama Sutra the Buddha says, 'When unseeing, why do you not see the unseeing? If you see the unseeing, it is no longer unseeing. If you do not see the unseeing, it is not an object. Why isn't it yourself?'" This reminds of Nagarjuna's Sunyatasaptati:

[51] The sense of sight is not inside the eye, not inside form, and not in between. [Therefore] an image depending upon form and eye is false.

[52] If the eye does not see itself, how can it see form? Therefore eye and form are without self. The same [is true for the] remaining sense-fields.

[53] Eye is empty of its own self [and] of another's self. Form is also empty. Likewise [for the] remaining sense-fields.[61]

Chinese texts

- 《開元釋教錄》:「沙門釋懷迪,循州人也,住本州羅浮山南樓寺。其山乃仙聖遊居之處。迪久習經論,多所該博,九流七略,粗亦討尋,但以居近海隅,數有梵僧遊止;迪就學書語,復皆通悉。往者三藏菩提流志譯寶積經,遠召迪來,以充證義。所為事畢,還歸故鄉。後因遊廣府遇一梵僧 (未得其名) , 齎梵經一夾,請共譯之,勒成十卷,即《大佛頂萬行首楞嚴經》是也。迪筆受經旨,緝綴文理。其梵僧傳經事畢,莫知所之。有因南使,流經至此。」

- 《舊唐書》卷七中宗紀云:「神龍元年正月…鳳閣侍郎韋承慶,正諫大夫房融,司禮卿韋慶等下獄……二月甲寅…韋承慶貶高要尉,房融配欽州。」《新唐書》〈中宗紀〉:「神龍元年二月甲寅......貶韋承慶為高要尉,流房融於高州。」新唐書卷139房琯傳:「父融,武后時以正諫大夫同鳳閣台平章事。神龍元年貶死高州。」《通鑑》卷208神龍元年:「二月乙卯正諫大夫同平章事房融除名流高州。」

- 《續古今譯經圖記》:「沙門般刺蜜帝,唐云極量,中印度人也。懷道觀方,隨缘濟度,展轉游化,達我支那。(印度國俗呼廣府為支那名帝京為摩訶支那) 乃於廣州制旨道場居止。眾知博達,祈请亦多。利物為心,敷斯秘賾。以神龍元年龍集乙巳五月己卯朔二十三日辛丑,遂於灌頂部中誦出一品名《大佛頂如来密因修證了義、諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經》一部(十卷)。烏萇國沙門彌迦釋迦(釋迦稍訛,正云鑠佉,此曰雲峰)譯語,菩薩戒弟子、前正諫大夫、同中書門下平章事、清河房融筆受,循州羅浮山南樓寺沙門懷迪證譯。其僧傳經事畢,汎舶西歸。有因南使,流通於此。」

- 玄睿《大乘三論大義鈔》:「遣德清法師等於唐檢之。德清法師承大唐法詳居士:《大佛頂經》是房融偽造,非真佛經也。智昇未詳,謬編正錄。」

- 梁啟超《古書真偽及其年代》:「真正的佛經並没有《楞嚴經》一類的話,可知《楞嚴經》一書是假書。」

Remove ads

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads