Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Spanish–American War

1898 conflict between Spain and the United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

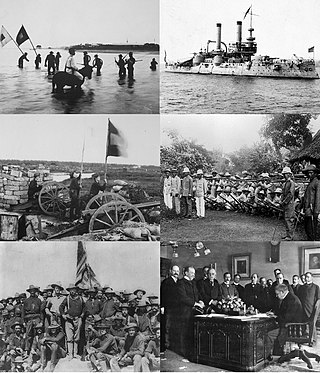

The Spanish–American War[a] (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the U.S. acquiring sovereignty over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and establishing a protectorate over Cuba. It represented U.S. intervention in the Cuban War of Independence and Philippine Revolution, with the latter later leading to the Philippine–American War. The Spanish–American War brought an end to almost four centuries of Spanish presence in the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific; the United States meanwhile not only became a major world power, but also gained several island possessions spanning the globe, which provoked rancorous debate over the wisdom of expansionism.[23]

The 19th century represented a clear decline for the Spanish Empire, while the United States went from a newly founded country to a rising power. In 1895, Cuban nationalists began a revolt against Spanish rule, which was brutally suppressed by the colonial authorities.[24] W. Joseph Campbell argues that yellow journalism in the U.S. exaggerated the atrocities in Cuba to sell more newspapers and magazines,[25] which swayed American public opinion in support of the rebels. But historian Andrea Pitzer also points to the actual shift toward savagery of the Spanish military leadership, who adopted the brutal reconcentration policy after replacing the relatively conservative Governor-General of Cuba Arsenio Martínez Campos with the more unscrupulous and aggressive Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed "The Butcher."[26][27] President Grover Cleveland resisted mounting demands for U.S. intervention, as did his successor William McKinley.[28] Though not seeking a war, McKinley made preparations in readiness for one.

In January 1898, the U.S. Navy armored cruiser USS Maine was sent to Havana to provide protection for U.S. citizens. After the Maine was sunk by a mysterious explosion in the harbor on February 15, 1898, political pressures pushed McKinley to receive congressional authority to use military force. On April 21, the U.S. began a blockade of Cuba,[5] and soon after Spain and the U.S. declared war. The war was fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, where American war advocates correctly anticipated that U.S. naval power would prove decisive. On May 1, a squadron of U.S. warships destroyed the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in the Philippines and captured the harbor. The first U.S. Marines landed in Cuba on June 10 in the island's southeast, moving west and engaging in the Battles of El Caney and San Juan Hill on July 1 and then destroying the fleet at and capturing Santiago de Cuba on July 17.[29] On June 20, the island of Guam surrendered without resistance, and on July 25, U.S. troops landed on Puerto Rico, of which a blockade had begun on May 8 and where fighting continued until an armistice was signed on August 13.

The war formally ended with the 1898 Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10 with terms favorable to the U.S. The treaty ceded ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S., and set Cuba up to become an independent state in 1902, although in practice it became a U.S. protectorate. The cession of the Philippines involved payment of $20 million ($760 million today) to Spain by the U.S. to cover infrastructure owned by Spain.[30] In Spain, the defeat in the war was a profound shock to the national psyche and provoked a thorough philosophical and artistic reevaluation of Spanish society known as the Generation of '98.[31]

Remove ads

Historical background

Summarize

Perspective

Spain's attitude towards its colonies

The combined problems arising from the Peninsular War (1807–1814), the loss of most of its colonies in the Americas in the early 19th-century Spanish American wars of independence, and three Carlist Wars (1832–1876) marked a low point for Spanish colonialism.[32] Liberal Spanish elites like Antonio Cánovas del Castillo and Emilio Castelar offered new interpretations of the concept of "empire" to dovetail with the emerging Spanish nationalism. Cánovas made clear in an address to the University of Madrid in 1882[33][34] his view of the Spanish nation as based on shared cultural and linguistic elements—on both sides of the Atlantic—that tied Spain's territories together.

Cánovas saw Spanish colonialism as more "benevolent" than that of other European colonial powers. The prevalent opinion in Spain before the war regarded the spreading of "civilization" and Christianity as Spain's main objective and contribution to the New World. The concept of cultural unity bestowed special significance on Cuba, which had been Spanish for almost four hundred years, and was viewed as an integral part of the Spanish nation. The focus on preserving the empire would have negative consequences for Spain's national pride in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War.[35]

American interest in the Caribbean

In 1823, the fifth American President James Monroe (1758–1831, served 1817–25) enunciated the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that the United States would not tolerate further efforts by European governments to retake or expand their colonial holdings in the Americas or to interfere with the newly independent states in the hemisphere. The U.S. would, however, respect the status of the existing European colonies. Before the American Civil War (1861–1865), Southern interests attempted to have the United States purchase Cuba and convert it into a new slave state. The pro-slavery element proposed the Ostend Manifesto of 1854. Anti-slavery forces rejected it.

After the American Civil War and Cuba's Ten Years' War, U.S. businessmen began monopolizing the devalued sugar markets in Cuba. In 1894, 90% of Cuba's total exports went to the United States, which also provided 40% of Cuba's imports.[36] Cuba's total exports to the U.S. were almost twelve times larger than the export to Spain.[37] U.S. business interests indicated that while Spain still held political authority over Cuba, it was the U.S. that held economic power over Cuba.

The U.S. became interested in a trans-isthmus canal in either Nicaragua or Panama and realized the need for naval protection. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was an exceptionally influential theorist; his ideas were much admired by future 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, as the U.S. rapidly built a powerful naval fleet of steel warships in the 1880s and 1890s. Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy from 1897 to 1898 and was an aggressive supporter of an American war with Spain over Cuban interests.

Meanwhile, the "Cuba Libre" movement, led by Cuban intellectual José Martí until he died in 1895, had established offices in Florida.[38] The face of the Cuban revolution in the U.S. was the "Cuban Junta", under the leadership of Tomás Estrada Palma, who in 1902 became Cuba's first president. The Junta dealt with leading newspapers and Washington officials and held fund-raising events across the U.S. It funded and smuggled weapons. It mounted an extensive propaganda campaign that generated enormous popular support in the U.S. in favor of the Cubans. Protestant churches and most Democrats were supportive, but business interests called on Washington to negotiate a settlement and avoid war.[39]

Cuba attracted enormous American attention, but almost no discussion involved the other Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, also in the Caribbean, or of the Philippines or Guam.[40] Historians note that there was no popular demand in the United States for an overseas colonial empire.[41]

Remove ads

Path to war

Summarize

Perspective

Cuban struggle for independence

The first serious bid for Cuban independence was the Ten Years' War, which erupted in 1868 and was subdued by the authorities a decade later. Neither the fighting nor the reforms in the Pact of Zanjón (February 1878) quelled the desire of some revolutionaries for wider autonomy and, ultimately, independence. One such revolutionary, José Martí, continued to promote Cuban financial and political freedom in exile. In early 1895, after years of organizing, Martí launched a three-pronged invasion of the island.[42]

The plan called for one group from Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic led by Máximo Gómez, one group from Costa Rica led by Antonio Maceo Grajales, and another from the United States (preemptively thwarted by U.S. officials in Florida) to land in different places on the island and provoke an uprising. While their call for revolution, the grito de Baire, was successful, the result was not the grand show of force Martí had expected. With a quick victory effectively lost, the revolutionaries settled in to fight a protracted guerrilla campaign.[42]

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the architect of Spain's Restoration constitution and the prime minister at the time, ordered General Arsenio Martínez-Campos, a distinguished veteran of the war against the previous uprising in Cuba, to quell the revolt. Campos's reluctance to accept his new assignment and his method of containing the revolt to the province of Oriente earned him criticism in the Spanish press.[43] The mounting pressure forced Cánovas to replace General Campos with General Valeriano Weyler, a soldier who had experience in quelling rebellions in overseas provinces and the Spanish metropole. Weyler deprived the insurgency of weaponry, supplies, and assistance by ordering the residents of some Cuban districts to move to reconcentration areas near the military headquarters.[43] This strategy was effective in slowing the spread of rebellion. In the United States, this fueled the fire of anti-Spanish propaganda.[44] In a political speech, President William McKinley used this to ram Spanish actions against armed rebels. He even said this "was not civilized warfare" but "extermination".[45][46]

Spanish attitude

Spain depended on Cuba for prestige and trade, and used it as a training ground for its army. Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo announced that "the Spanish nation is disposed to sacrifice to the last peseta of its treasure and to the last drop of blood of the last Spaniard before consenting that anyone snatch from it even one piece of its territory".[47] He had long dominated and stabilized Spanish politics. He was assassinated in 1897 by Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo,[48] leaving a Spanish political system that was not stable and could not risk a blow to its prestige.[49]

US response

The eruption of the Cuban revolt, Weyler's measures, and the popular fury these events whipped up proved to be a boon to the newspaper industry in New York City. Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World and William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal recognized the potential for great headlines and stories that would sell copies. Both papers denounced Spain but had little influence outside New York. American opinion generally saw Spain as a hopelessly backward power that was unable to deal fairly with Cuba. American Catholics were divided before the war began but supported it enthusiastically once it started.[50][51]

The U.S. had important economic interests that were being harmed by the prolonged conflict and deepening uncertainty about Cuba's future. Shipping firms that had relied heavily on trade with Cuba now suffered losses as the conflict continued unresolved.[52] These firms pressed Congress and McKinley to seek an end to the revolt. Other American business concerns, specifically those who had invested in Cuban sugar, looked to the Spanish to restore order.[53] Stability, not war, was the goal of both interests. How stability would be achieved would depend largely on the ability of Spain and the U.S. to work out their issues diplomatically.

Lieutenant Commander Charles Train, in 1894, in his preparatory notes in an outlook of an armed conflict between Spain and the United States, wrote that Cuba was entirely dependent on the outside world for food supplies, coal, and maritime supplies and that Spain would not be able to resupply a naval expeditionary force locally.[54]

While tension increased among the Cubans and Spanish government, popular support of intervention began to spring up in the United States. Many Americans likened the Cuban revolt to the American Revolution, and they viewed the Spanish government as a tyrannical oppressor. Historian Louis Pérez notes that "The proposition of war in behalf of Cuban independence took hold immediately and held on thereafter. Such was the sense of the public mood." Many poems and songs were written in the United States to express support of the "Cuba Libre" movement.[55] At the same time, many African Americans, facing growing racial discrimination and increasing retardation of their civil rights, wanted to take part in the war. They saw it as a way to advance the cause of equality, service to country hopefully helping to gain political and public respect amongst the wider population.[56]

President McKinley, well aware of the political complexity surrounding the conflict, wanted to end the revolt peacefully. He began to negotiate with the Spanish government, hoping that the talks would dampen yellow journalism in the United States and soften support for war with Spain. An attempt was made to negotiate a peace before McKinley took office. However, the Spanish refused to take part in the negotiations. In 1897 McKinley appointed Stewart L. Woodford as the new minister to Spain, who again offered to negotiate a peace. In October 1897, the Spanish government refused the United States' offer to negotiate between the Spanish and the Cubans, but promised the U.S. it would give the Cubans more autonomy.[57] However, with the election of a more liberal Spanish government in November, Spain began to change its policies in Cuba. First, the new Spanish government told the United States that it was willing to offer a change in the Reconcentration policies if the Cuban rebels agreed to a cessation of hostilities. This time the rebels refused the terms in hopes that continued conflict would lead to U.S. intervention and the creation of an independent Cuba.[57] The liberal Spanish government also recalled the Spanish Governor-General Valeriano Weyler from Cuba. This action alarmed many Cubans loyal to Spain.[58]

The Cubans loyal to Weyler began planning large demonstrations to take place when the next Governor General, Ramón Blanco, arrived in Cuba. U.S. consul Fitzhugh Lee learned of these plans and sent a request to the U.S. State Department to send a U.S. warship to Cuba.[58] This request led to the armored cruiser USS Maine being sent to Cuba. While Maine was docked in Havana harbor, a spontaneous explosion sank the ship. The sinking of Maine was blamed on the Spanish and made the possibility of a negotiated peace very slim.[59] Throughout the negotiation process, the major European powers, especially Britain, France, and Russia, generally supported the American position and urged Spain to give in.[60] Spain repeatedly promised specific reforms that would pacify Cuba but failed to deliver; American patience ran out.[61]

USS Maine dispatch to Havana and loss

The sunken USS Maine in Havana harbor

Though publication of a U.S. Navy investigation report would take a month, this Washington D.C. newspaper[62] was among those asserting within one day that the explosion was not accidental.

McKinley sent USS Maine to Havana to ensure the safety of American citizens and interests, and to underscore the urgent need for reform. Naval forces were moved in position to attack simultaneously on several fronts if the war was not avoided. As Maine left Florida, a large part of the North Atlantic Squadron was moved to Key West and the Gulf of Mexico. Others were also moved just off the shore of Lisbon, and others were moved to Hong Kong.[63]

At 9:40 P.M. on February 15, 1898, Maine sank in Havana Harbor after suffering a massive explosion. More than 3/4 of the ship's crew of 355 sailors, officers and Marines died as a result of the explosion. Of the 94 survivors only 16 were uninjured.[64] In total, 260[65] servicemen were killed in the initial explosion, and six more died shortly thereafter from injuries.[65]

While McKinley urged patience and did not declare that Spain had caused the explosion, the deaths of hundreds of American[66] sailors held the public's attention. McKinley asked Congress to appropriate $50 million for defense, and Congress unanimously obliged. Most American leaders believed that the cause of the explosion was unknown. Still, public attention was now riveted on the situation and Spain could not find a diplomatic solution to avoid war. Spain appealed to the European powers, most of whom advised it to accept U.S. conditions for Cuba in order to avoid war.[67] Germany urged a united European stand against the United States but took no action.[68]

The U.S. Navy's investigation, made public on March 28, concluded that the ship's powder magazines were ignited when an external explosion was set off under the ship's hull. Report investigation omitted to place responsibility for the external explosion but nonetheless poured fuel on popular indignation in the U.S., making war virtually inevitable.[69] Spain's investigation came to the opposite conclusion: the explosion originated within the ship. Other investigations in later years came to various contradictory conclusions, but had no bearing on the coming of the war. In 1974, Admiral Hyman George Rickover had his staff look at the documents and decided there was an internal explosion.[70] A study commissioned by National Geographic magazine in 1999, using AME computer modeling, reported: "By examining the bottom plating of the ship and how it bent and folded, AME concluded that the destruction could have been caused by a mine."[70]

Declaring war

After Maine was destroyed, New York City newspaper publishers Hearst and Pulitzer decided that the Spanish were to blame, and they publicized this theory as fact in their papers.[71] Even prior to the explosion, both had published sensationalistic accounts of "atrocities" committed by the Spanish in Cuba; headlines such as "Spanish Murderers" were commonplace in their newspapers. Following the explosion, this tone escalated with the headline "Remember The Maine, To Hell with Spain!", quickly appearing.[72][73] Their press exaggerated what was happening and how the Spanish were treating the Cuban prisoners.[74] The stories were based on factual accounts, but most of the time, the articles that were published were embellished and written with incendiary language causing emotional and often heated responses among readers. A common myth falsely states that when illustrator Frederic Remington said there was no war brewing in Cuba, Hearst responded: "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."[75]

However, this new "yellow journalism" was uncommon outside New York City, and historians no longer consider it the major force shaping the national mood.[76] Public opinion nationwide did demand immediate action, overwhelming the efforts of President McKinley, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed, and the business community to find a negotiated solution. Wall Street, big business, high finance and Main Street businesses across the country were vocally opposed to war and demanded peace.[77] After years of severe depression, the economic outlook for the domestic economy was suddenly bright again in 1897. However, the uncertainties of warfare posed a serious threat to full economic recovery. "War would impede the march of prosperity and put the country back many years," warned the New Jersey Trade Review. The leading railroad magazine editorialized, "From a commercial and mercenary standpoint it seems peculiarly bitter that this war should come when the country had already suffered so much and so needed rest and peace." McKinley paid close attention to the strong antiwar consensus of the business community, and strengthened his resolve to use diplomacy and negotiation rather than brute force to end the Spanish tyranny in Cuba.[78] Historian Nick Kapur argues that McKinley's actions as he moved toward war were rooted not in various pressure groups but in his deeply held "Victorian" values, especially arbitration, pacifism, humanitarianism, and manly self-restraint.[79]

A speech delivered by Republican Senator Redfield Proctor of Vermont on March 17, 1898, thoroughly analyzed the situation and greatly strengthened the pro-war cause. Proctor concluded that war was the only answer.[80] Many in the business and religious communities which had until then opposed war, switched sides, leaving McKinley and Speaker Reed almost alone in their resistance to a war.[81][82][83] On April 11, McKinley ended his resistance and asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba to end the civil war there, knowing that Congress would force a war.

On April 19, while Congress was considering joint resolutions supporting Cuban independence, Republican Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado proposed the Teller Amendment to ensure that the U.S. would not establish permanent control over Cuba after the war. The amendment, disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba, passed the Senate 42 to 35; the House concurred the same day, 311 to 6. The amended resolution demanded Spanish withdrawal and authorized the President to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuba gain independence from Spain. President McKinley signed the joint resolution on April 20, 1898, and the ultimatum was sent to Spain.[84] In response, Spain severed diplomatic relations with the United States on April 21. On the same day, the U.S. Navy began a blockade of Cuba.[5]

On April 25, the U.S. Congress responded in kind, declaring that a state of war between the U.S. and Spain had de facto existed since April 21, the day the blockade of Cuba had begun.[5] It was the embodiment of the naval plan created by Lieutenant Commander Charles Train four years ago, stating once the US enacted a proclamation of war against Spain, it would mobilize its North Atlantic Squadron to form an efficient blockade in Havana, Matanzas and Sagua La Grande.[54]

The Navy was ready, but the Army was not well-prepared for the war and made radical changes in plans and quickly purchased supplies. In the spring of 1898, the strength of the U.S. Regular Army was just 24,593 soldiers. The Army wanted 50,000 new men but received over 220,000 through volunteers and the mobilization of state National Guard units,[85] even gaining nearly 100,000 men on the first night after the explosion of USS Maine.[86]

President McKinley issued two calls for volunteers, the first on April 23 which called for 125,000 men to enlist, followed by a second appeal for a further 75,000 volunteers.[87] States in the Northeast, Midwest, and the West quickly filled their volunteer quota. In response to the surplus influx of volunteers, several Northern states had their quotas increased. Contrastingly, some Southern states struggled to fulfil even the first mandated quota, namely Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia.[88]

The majority of states did not allow African-American men to volunteer, which impeded recruitment in Southern states, especially those with large African-American populations. Quota requirements, based on total population, were unmanageable, as they were disproportionate compared to the actual population permitted to volunteer.[89] This was especially evident in some states, such as Kentucky and Mississippi, which accepted out-of-state volunteers to aid in meeting their quotas.[90]

This Southern apprehension towards enlistment can also be attributed to "a war weariness derived from the Confederacy's defeat in the Civil War."[91] Many in the South were still recuperating financially after their losses in the Civil War, and the upcoming war did not provide much hope for economic prosperity in the South. The prospect of a naval war gave anxiety to those in the South. The financial security of those working and living in the cotton belt relied heavily upon trade across the Atlantic, which would be disrupted by a nautical war, the prospect of which fostered a reluctance to enlist.[92] Potential volunteers were also not financially incentivized, with pay per month initially being $13.00, which then was then raised to $15.60 for combat pay.[93] It was more economically promising for most Southern men to continue in their own enterprises rather than enlist.

Historiography

The overwhelming consensus of observers in the 1890s, and historians ever since, is that an upsurge of humanitarian concern with the plight of the Cubans was the main motivating force that caused the war with Spain in 1898. McKinley put it succinctly in late 1897 that if Spain failed to resolve its crisis, the United States would see "a duty imposed by our obligations to ourselves, to civilization and humanity to intervene with force".[45] Intervention in terms of negotiating a settlement proved impossible—neither Spain nor the insurgents would agree. Louis Perez states, "Certainly the moralistic determinants of war in 1898 has been accorded preponderant explanatory weight in the historiography."[94] By the 1950s, however, American political scientists began attacking the war as a mistake based on idealism, arguing that a better policy would be realism. They discredited the idealism by suggesting the people were deliberately misled by propaganda and sensationalist yellow journalism. Political scientist Robert Osgood, writing in 1953, led the attack on the American decision process as a confused mix of "self-righteousness and genuine moral fervor," in the form of a "crusade" and a combination of "knight-errantry and national self- assertiveness."[95] Osgood argued:

- A war to free Cuba from Spanish despotism, corruption, and cruelty, from the filth and disease and barbarity of General 'Butcher' Weyler's reconcentration camps, from the devastation of haciendas, the extermination of families, and the outraging of women; that would be a blow for humanity and democracy.... No one could doubt it if he believed—and skepticism was not popular—the exaggerations of the Cuban Junta's propaganda and the lurid distortions and imaginative lies pervade by the "yellow sheets" of Hearst and Pulitzer at the combined rate of 2 million [newspaper copies] a day.[96]

In his War and Empire,[97] Prof. Paul Atwood of the University of Massachusetts (Boston) writes:

The Spanish–American War was fomented on outright lies and trumped up accusations against the intended enemy. ... War fever in the general population never reached a critical temperature until the accidental sinking of the USS Maine was deliberately, and falsely, attributed to Spanish villainy. ... In a cryptic message ... Senator Lodge wrote that 'There may be an explosion any day in Cuba which would settle a great many things. We have got a battleship in the harbor of Havana, and our fleet, which overmatches anything the Spanish have, is masked at the Dry Tortugas.

In his autobiography,[98] Theodore Roosevelt gave his views of the origins of the war:

Our own direct interests were great, because of the Cuban tobacco and sugar, and especially because of Cuba's relation to the projected Isthmian [Panama] Canal. But even greater were our interests from the standpoint of humanity. ... It was our duty, even more from the standpoint of National honor than from the standpoint of National interest, to stop the devastation and destruction. Because of these considerations I favored war.

In the article 'Meaning of the Main', Louis A. Perez Jr. challenges Roosevelt's assertion:

The Maine incident fits well into a larger idealized view of a political universe. It lends itself easily to the service of validating normative democratic theory. It adds credence to commonly shared values of the national mission. This indeed may be a central if unspoken element of much of the historiography and the larger ideological role of the Maine: a plausible denial of the proposition of war as an instrument of policy-war, in short, deliberate and by design, for the purpose of territorial expansion.[99]

Remove ads

Pacific theater

Summarize

Perspective

Philippines

In the 333 years of Spanish rule, the Philippines developed from a small overseas colony governed from the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain to a land with modern elements in the cities. The Spanish-speaking middle classes of the 19th century were mostly educated in the liberal ideas coming from Europe. Among these Ilustrados was the Filipino national hero José Rizal, who demanded larger reforms from the Spanish authorities. This movement eventually led to the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial rule. The revolution had been in a state of truce since the signing of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato in 1897, with revolutionary leaders having accepted exile outside of the country.

Lt. William Warren Kimball, Staff Intelligence Officer with the Naval War College[100] prepared a plan for war with Spain including the Philippines on June 1, 1896, known as "the Kimball Plan".[101]

On April 23, 1898, a document from Governor General Basilio Augustín appeared in the Manila Gazette newspaper warning of the impending war and calling for Filipinos to participate on the side of Spain.[h]

Roosevelt, who was at that time Assistant Secretary of the Navy, ordered Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy: "Order the squadron ...to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war with Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands." Dewey's squadron departed on April 27 for the Philippines, reaching Manila Bay on the evening of April 30.[106]

The first battle between American and Spanish forces was at Manila Bay where, on May 1, Commodore Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron aboard USS Olympia, in a matter of hours defeated a Spanish squadron under Admiral Patricio Montojo.[i] Dewey managed this with only nine wounded.[108][109] With the German seizure of Qingdao in 1897, Dewey's squadron had become the only naval force in the Far East without a local base of its own, and was beset with coal and ammunition problems.[110] Despite these problems, the Asiatic Squadron destroyed the Spanish fleet and captured Manila's harbor.[110]

Following Dewey's victory, Manila Bay became filled with the warships of other naval powers.[110] The German squadron of eight ships, ostensibly in Philippine waters to protect German interests, acted provocatively—cutting in front of American ships, refusing to salute the American flag (according to customs of naval courtesy), taking soundings of the harbor, and landing supplies for the besieged Spanish.[112]

With interests of their own, Germany was eager to take advantage of whatever opportunities the conflict in the islands might afford.[113] There was a fear at the time that the islands would become a German possession.[114] The Americans called Germany's bluff and threatened conflict if the aggression continued. The Germans backed down.[113][115] At the time, the Germans expected the confrontation in the Philippines to end in an American defeat, with the revolutionaries capturing Manila and leaving the Philippines ripe for German picking.[116] The United States government had concerns about the self-government capability of the Filipinos, fearing that a power such as Germany or Japan might take control if the United States did not do so.[117]

Commodore Dewey transported Emilio Aguinaldo, a Filipino leader who led rebellion against Spanish rule in the Philippines in 1896, from exile in Hong Kong to the Philippines to rally more Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government.[9] By June 9, Aguinaldo's forces controlled the provinces of Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Bataan, Zambales, Pampanga, Pangasinan, and Mindoro, and had laid siege to Manila.[118] On June 12, Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines.[119][120] While Aguinaldo's revolutionary forces were fighting, preparations were underway in the U.S. to send land forces to supplement Dewey's naval forces.[121] Troops began departing San Francisco on May 25 and arriving on Manila on June 30,[122] having been officially formed as the U.S. Army the U.S. Eighth Army Corps on June 21 while they were in transit.

On August 5, upon instruction from Spain, Governor-General Basilio Augustin turned over the command of the Philippines to his deputy, Fermin Jaudenes.[123] On August 13, with American commanders unaware that a peace protocol had been signed between Spain and the U.S. on the previous day in Washington D.C., American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish in the Battle of Manila.[c][9][10] This battle marked the end of Filipino–American collaboration, as the American action of preventing Filipino forces from entering the captured city of Manila was deeply resented by the Filipinos. This later led to the Philippine–American War,[124] which would prove to be more deadly and costly than the Spanish–American War.

The U.S. had sent a force of some 11,000 ground troops to the Philippines. On August 14, 1898, Spanish Captain-General Jaudenes formally capitulated and U.S. General Merritt formally accepted the surrender and declared the establishment of a U.S. military government in occupation. The capitulation document declared, "The surrender of the Philippine Archipelago." and set forth a mechanism for its physical accomplishment.[125][126] That same day, the Schurman Commission recommended that the U.S. retain control of the Philippines, possibly granting independence in the future.[127] On December 10, 1898, the Spanish government ceded the Philippines to the United States in the Treaty of Paris. Armed conflict broke out between U.S. forces and the Filipinos when U.S. troops began to take the place of the Spanish in control of the country after the end of the war, quickly escalating into the Philippine–American War.

Guam

On June 20, 1898, the protected cruiser USS Charleston commanded by Captain Henry Glass, and three transports carrying troops to the Philippines, entered Guam's Apia Harbor. Captain Glass had opened sealed orders instructing him to proceed to Guam and capture it while en route to the Philippines. Charleston fired a few rounds at the abandoned Fort Santa Cruz without receiving return fire. Two local officials, not knowing that war had been declared and believing the firing had been a salute, came out to Charleston to apologize for their inability to return the salute as they were out of gunpowder. Glass informed them that the U.S. and Spain were at war.[128]

The following day, Glass sent Lieutenant William Braunersreuther to meet the Spanish Governor to arrange the surrender of the island and the Spanish garrison there. Two officers, 54 Spanish infantrymen as well as the governor-general and his staff were taken prisoner[citation needed] and transported to the Philippines as prisoners of war. No U.S. forces were left on Guam, but the only U.S. citizen on the island, Frank Portusach, told Captain Glass that he would look after things until U.S. forces returned.[128]

Remove ads

Caribbean theater

Summarize

Perspective

Cuba

Theodore Roosevelt advocated intervention in Cuba, both for the Cuban people and to promote the Monroe Doctrine. While Assistant Secretary of the Navy, he placed the Navy on a war-time footing and prepared Dewey's Asiatic Squadron for battle. He also worked with Leonard Wood in convincing the Army to raise an all-volunteer regiment, the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. Wood was given command of the regiment that quickly became known as the "Rough Riders".[129]

The Americans planned to destroy Spain's army forces in Cuba, capture the port city of Santiago de Cuba, and destroy the Spanish Caribbean Squadron (also known as the Flota de Ultramar). To reach Santiago they had to pass through concentrated Spanish defenses in the San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. The American forces were aided in Cuba by the pro-independence rebels led by General Calixto García.

Cuban sentiment

For quite some time the Cuban public believed the United States government to possibly hold the key to its independence, and even annexation was considered for a time, which historian Louis Pérez explored in his book Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy. The Cubans harbored a great deal of discontent towards the Spanish government, a result of years of manipulation on the part of the Spanish. The prospect of getting the United States involved in the fight was considered by many Cubans as a step in the right direction. While the Cubans were wary of the United States' intentions, the overwhelming support from the American public provided the Cubans with some peace of mind, because they believed that the United States was committed to helping them achieve their independence.[130]

Action at Cienfuegos

The first combat between American and Spanish forces in the Caribbean occurred on May 11, 1898, in the harbor near the city of Cienfuegos.[131] The city was the southern terminus for undersea communication cables that connected Cuba to Spain and other Spanish holdings in the Caribbean. American Naval officers needed to destroy these cables to cut communications into and out of Cuba, in preparation for later operations against the major city of Santiago.[132] The USS Marblehead and the USS Nashville were dispatched to cut these cables early on the morning of May 11. To cut the cables, two steam cutters, with a crew of eight sailors and six Marines each, and two sailing launches, with a crew of fourteen sailors each, maneuvered into harbor and within 200 feet from shore.[132]

While the boats moved towards shore, the Marblehead and Nashville shelled Spanish trenches dug to protect the cables from sabotage attempts. They succeeded in destroying support buildings for the cables and drove the Spanish force back away from the beach. The boats' crews pulled one cable up and began trying to cut through its metal jacket while Spanish soldiers started firing from cover. Marine sharpshooters returned fire from the boats and the Marblehead and Nashville began firing shrapnel shells in an attempt to force the Spanish completely out of the area.[132] The sailors finished cutting one cable and pulled up a second one to begin severing it too. Spanish fire began to take a toll on the Marines and sailors with multiple casualties in the small boats, but the Americans were still able to cut a second wire. They began working on the final wire and succeeded in partially cutting it until the still heavy Spanish fire and mounting casualties forced the Navy officer in command, Lieutenant E. A. Anderson, to order the boats to return to the cover of the larger vessels.[132]

In the almost three hours of combat, two men were killed, two mortally wounded, and four more seriously wounded and they succeeded in severing two of the three cables running out of Cienfuegos.[133] This relatively brief fight significantly disrupted communications between Cuba, Santiago, and Spain and contributed to the overall American goal of isolating Cuba from outside support. It also provided a major boost to American morale because it was the first combat American servicemen had seen close to home. For their brave actions, all the Marines and sailors in the four small boats received the Medal of Honor.[133]

Land campaign

The first American landings in Cuba occurred on June 10 with the landing of the First Marine Battalion at Fisherman's Point in Guantánamo Bay.[135] This was followed on June 22 to 24, when the Fifth Army Corps under General William R. Shafter landed at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established an American base of operations. A contingent of Spanish troops, having fought a skirmish with the Americans near Siboney on June 23, had retired to their lightly entrenched positions at Las Guasimas. An advance guard of U.S. forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and engaged the Spanish rearguard of about 2,000 soldiers led by General Antero Rubín[136] who effectively ambushed them, in the Battle of Las Guasimas on June 24. The battle ended indecisively in favor of Spain and the Spanish left Las Guasimas on their planned retreat to Santiago.

The U.S. Army employed Civil War–era skirmishers at the head of the advancing columns. Three of four of the U.S. soldiers who had volunteered to act as skirmishers walking point at the head of the American column were killed, including Hamilton Fish II (grandson of Hamilton Fish, the Secretary of State under Ulysses S. Grant), and Captain Allyn K. Capron, whom Theodore Roosevelt would describe as one of the finest natural leaders and soldiers he ever met. Only Oklahoma Territory Pawnee Indian, Tom Isbell, wounded seven times, survived.[137]

Regular Spanish troops were mostly armed with modern charger-loaded, 7mm 1893 Spanish Mauser rifles and using smokeless powder. The high-speed 7×57mm Mauser round was termed the "Spanish Hornet" by the Americans because of the supersonic crack as it passed overhead. Other irregular troops were armed with Remington Rolling Block rifles in .43 Spanish using smokeless powder and brass-jacketed bullets. U.S. regular infantry were armed with the .30–40 Krag–Jørgensen, a bolt-action rifle with a complex magazine. Both the U.S. regular cavalry and the volunteer cavalry used smokeless ammunition. In later battles, state volunteers used the .45–70 Springfield, a single-shot black powder rifle.[137]

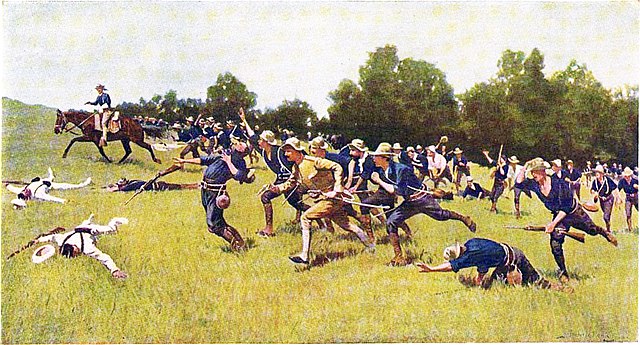

On July 1, a combined force of about 15,000 American troops in regular infantry and cavalry regiments, including all four of the army's "Colored" Buffalo Soldier regiments, and volunteer regiments, among them Roosevelt and his "Rough Riders", the 71st New York, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, and 1st North Carolina, and rebel Cuban forces attacked 1,270 entrenched Spaniards in dangerous Civil War-style frontal assaults at the Battle of El Caney and Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago.[138] More than 200 U.S. soldiers were killed and close to 1,200 wounded in the fighting, thanks to the high rate of fire the Spanish put down range at the Americans.[139] Charles A. Wikoff, a U.S. Army colonel who was killed in action, was the most senior U.S. Army officer killed in the Spanish–American War.[140] Supporting fire by Gatling guns was critical to the success of the assault.[141][142] Cervera decided to escape Santiago two days later. First Lieutenant John J. Pershing, nicknamed "Black Jack", oversaw the 10th Cavalry Unit during the war. Pershing and his unit fought in the Battle of San Juan Hill. Pershing was cited for his gallantry during the battle.

The Spanish forces at Guantánamo were so isolated by Marines and Cuban forces that they did not know that Santiago was under siege, and their forces in the northern part of the province could not break through Cuban lines. This was not true of the Escario relief column from Manzanillo,[143] which fought its way past determined Cuban resistance but arrived too late to participate in the siege.

After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the American advance halted. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a bloody, strangling siege of the city.[144] During the nights, Cuban troops dug successive series of "trenches" (raised parapets), toward the Spanish positions. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by U.S. soldiers and a new set of excavations went forward. American troops, while suffering daily losses from Spanish fire, suffered far more casualties from heat exhaustion and mosquito-borne disease.[145] At the western approaches to the city, Cuban general Calixto Garcia began to encroach on the city, causing much panic and fear of reprisals among the Spanish forces.

Battle of Tayacoba

Lieutenant Carter P. Johnson of the Buffalo Soldiers' 10th Cavalry, with experience in special operations roles as head of the 10th Cavalry's attached Apache scouts in the Apache Wars, chose 50 soldiers from the regiment to lead a deployment mission with at least 375 Cuban soldiers under Cuban Brigadier General Emilio Nunez and other supplies to the mouth of the San Juan River east of Cienfuegos. On June 29, 1898, a reconnaissance team in landing boats from the transports Florida and Fanita attempted to land on the beach, but were repelled by Spanish fire. A second attempt was made on June 30, 1898, but a team of reconnaissance soldiers was trapped on the beach near the mouth of the Tallabacoa River. A team of four soldiers saved this group and were awarded Medals of Honor. The USS Peoria and the recently arrived USS Helena then shelled the beach to distract the Spanish while the Cuban deployment landed 40 miles east at Palo Alto, where they linked up with Cuban General Gomez.[146][147]

Naval operations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

The major port of Santiago de Cuba was the main target of naval operations during the war. The U.S. fleet attacking Santiago needed shelter from the summer hurricane season; Guantánamo Bay, with its excellent harbor, was chosen. The 1898 invasion of Guantánamo Bay happened between June 6 and 10, with the first U.S. naval attack and subsequent successful landing of U.S. Marines with naval support.[148][149]

On April 23, a council of senior admirals of the Spanish Navy had decided to order Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete's squadron of four armored cruisers and three torpedo boat destroyers to proceed from their present location in Cape Verde (having left from Cádiz, Spain) to the West Indies.[150]

In May, the fleet of Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete had been spotted in Santiago harbor by American forces, where they had taken shelter for protection from sea attack. A two-month stand-off between Spanish and American naval forces followed.

U.S. Assistant Naval Constructor, Lieutenant Richmond Pearson Hobson was ordered by Rear Admiral William T. Sampson to sink the collier USS Merrimac in the harbor to bottle up the Spanish fleet. The mission was a failure, and Hobson and his crew were captured though Hobson soon became a national hero for leading what was widely reported as a suicide mission. Upon release, Hobson was presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor and promoted to Captain.[k]

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, was the largest naval engagement of the Spanish–American War. When the Spanish squadron finally attempted to leave the harbor on July 3, the American forces destroyed or grounded five of the six ships. Only one Spanish vessel, the new armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón, survived, but her captain hauled down her flag and scuttled her when the Americans finally caught up with her. The 1,612 Spanish sailors who were captured and sent to Seavey's Island at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, where they were confined at Camp Long as prisoners of war from July 11 until mid-September. The Americans treated Spain's officers, soldiers, and sailors with great respect. Ultimately, Spanish prisoners were returned to Spain with their "honors of war" on American ships. Admiral Cervera received different treatment from the sailors taken to Portsmouth. For a time, he was held at Annapolis, Maryland, where he was received with great enthusiasm by the people of that city.[152]

U.S. withdrawal

Yellow fever had spread quickly among the American occupation force, crippling it. A group of concerned officers of the American army chose Theodore Roosevelt to draft a request to Washington that it withdraw the Army, a request that paralleled a similar one from General Shafter, who described his force as an "army of convalescents". By the time of his letter, 75% of the force in Cuba was unfit for service.[153]

On August 7, the American invasion force started to leave Cuba. The evacuation was not total. The U.S. Army kept the black Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment in Cuba to support the occupation. The logic was that their race and the fact that many black volunteers came from southern states would protect them from disease; this logic led to these soldiers being nicknamed "Immunes". Still, when the Ninth left, 73 of its 984 soldiers had contracted the disease.[153]

Puerto Rico

On May 24, 1898, in a letter to Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge wrote, "Porto Rico is not forgotten and we mean to have it".[154]

In the same month, Lt. Henry H. Whitney of the United States Fourth Artillery was sent to Puerto Rico on a reconnaissance mission, sponsored by the Army's Bureau of Military Intelligence. He provided maps and information on the Spanish military forces to the U.S. government before the invasion.

The American offensive began on May 12, 1898, when a squadron of 12 U.S. ships commanded by Rear Adm. William T. Sampson of the United States Navy attacked the archipelago's capital, San Juan. Though the damage inflicted on the city was minimal, the Americans established a blockade in the city's harbor, San Juan Bay. On June 22, the cruiser Isabel II and the destroyer Terror delivered a Spanish counterattack, but were unable to break the blockade and Terror was damaged.

The land offensive began on July 25, when 1,300 infantry soldiers led by Nelson A. Miles disembarked off the coast of Guánica. The first organized armed opposition occurred in Yauco in what became known as the Battle of Yauco.[citation needed]

This encounter was followed by the Battle of Fajardo. The United States seized control of Fajardo on August 1, but were forced to withdraw on August 5 after a group of 200 Puerto Rican-Spanish soldiers led by Pedro del Pino gained control of the city, while most civilian inhabitants fled to a nearby lighthouse. The Americans encountered larger opposition during the Battle of Guayama and as they advanced towards the main island's interior. They engaged in crossfire at Guamaní River Bridge, Coamo and Silva Heights and finally at the Battle of Asomante.[7] The battles were inconclusive as the allied soldiers retreated.

A battle in San Germán concluded in a similar fashion with the Spanish retreating to Lares. On August 9, 1898, American troops that were pursuing units retreating from Coamo encountered heavy resistance in Aibonito in a mountain known as Cerro Gervasio del Asomante and retreated after six of their soldiers were injured. They returned three days later, reinforced with artillery units and attempted a surprise attack. In the subsequent crossfire, confused soldiers reported seeing Spanish reinforcements nearby and five American officers were gravely injured, which prompted a retreat order. All military actions in Puerto Rico were suspended on August 13, after U.S. President William McKinley and French ambassador Jules Cambon, acting on behalf of the Spanish government, signed an armistice whereby Spain relinquished its sovereignty over Puerto Rico.[7]

Remove ads

Cámara's squadron

Summarize

Perspective

Shortly after the war began in April, the Spanish Navy ordered major units of its fleet to concentrate at Cádiz in southern Spain to form the 2nd Squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Livermoore.[155] Two of Spain's most powerful warships, the battleship Pelayo and the brand-new armored cruiser Emperador Carlos V, were not available when the war began—the former undergoing reconstruction in a French shipyard and the latter not yet delivered from her builders—but both were rushed into service and assigned to Cámara's squadron.[156] The squadron was ordered to guard the Spanish coast against raids by the U.S. Navy. No such raids materialized. While Cámara's squadron lay idle at Cádiz, U.S. Navy forces destroyed Montojo's squadron at Manila Bay on 1 May and bottled up Cervera's squadron at Santiago de Cuba on 27 May.

During May, the Spanish Ministry of the Navy considered options for employing Cámara's squadron. Minister of the Navy Ramón Auñón y Villalón made plans for Cámara to take a portion of his squadron across the Atlantic Ocean and bombard a city on the East Coast of the United States, preferably Charleston, South Carolina, and then head for the Caribbean to make port at San Juan, Havana, or Santiago de Cuba,[157] but in the end this idea was dropped. Meanwhile, U.S. intelligence reported rumors as early as 15 May that Spain also was considering sending Cámara's squadron to the Philippines to destroy Dewey's squadron and reinforce the Spanish forces there with fresh troops.[158] Pelayo and Emperador Carlos V each were more powerful than any of Dewey's ships, and the possibility of their arrival in the Philippines was of great concern to the United States, which hastily arranged to dispatch 10,000 additional U.S. Army troops to the Philippines and send two U.S. Navy monitors to reinforce Dewey.[158]

On 15 June, Cámara finally received orders to depart immediately for the Philippines. His squadron, made up of Pelayo (his flagship), Emperador Carlos V, two auxiliary cruisers, three destroyers, and four colliers, was to depart Cádiz escorting four transports. After detaching two of the transports to steam independently to the Caribbean, his squadron was to proceed to the Philippines, escorting the other two transports, which carried 4,000 Spanish Army troops to reinforce Spanish forces there. He then was to destroy Dewey's squadron.[159][157][160] Accordingly, he sortied from Cádiz on 16 June[161] and, after detaching two of the transports for their voyages to the Caribbean, passed Gibraltar on 17 June[159] and arrived at Port Said, at the northern end of the Suez Canal, on 26 June.[162] There he found that U.S. operatives had purchased all the coal available at the other end of the canal in Suez to prevent his ships from coaling with it.[163] He also received word on 29 June from the British government, which controlled Egypt at the time, that his squadron was not permitted to coal in Egyptian waters because to do so would violate Egyptian and British neutrality.[162][157]

Ordered to continue,[164] Cámara's squadron passed through the Suez Canal on 5–6 July. By that time, word had reached Spain of the annihilation of Cervera's squadron off Santiago de Cuba on 3 July, freeing up the U.S. Navy's heavy forces from the blockade there, and the United States Department of the Navy had announced that a U.S. Navy "armored squadron with cruisers" would assemble and "proceed at once to the Spanish coast."[164] Fearing for the safety of the Spanish coast, the Spanish Ministry of the Navy recalled Cámara's squadron, which by then had reached the Red Sea, on 7 July 1898.[165] Cámara's squadron returned to Spain, making stops at Mahón on Menorca in the Balearic Islands on 18 July[166] and at Cartagena on either 20[166] or 23 July[157], according to different sources, before arriving at Cadiz,[157] where it was dissolved on 25 July 1898.[167] No U.S. Navy forces subsequently threatened the coast of Spain, and Cámara and Spain's two most powerful warships thus never saw combat during the war.[157]

Remove ads

Making peace

Summarize

Perspective

With defeats in Cuba and the Philippines, and its fleets in both places destroyed, Spain sued for peace and negotiations were opened between the two parties. After the sickness and death of British consul Edward Henry Rawson-Walker, American admiral Dewey requested the Belgian consul to Manila, Édouard André, to take Rawson-Walker's place as intermediary with the Spanish government.[168][169][170]

Hostilities were halted on August 12, 1898, with the signing in Washington of a Protocol of Peace between the United States and Spain.[6] After over two months of difficult negotiations, the formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, was signed in Paris on December 10, 1898, the United States acquired Spain's colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines in the treaty, and Cuba became a U.S. protectorate.[11] The treaty came into force in Cuba on April 11, 1899, with Cubans participating only as observers. Having been occupied since July 17, 1898, and thus under the jurisdiction of the U.S. military government, Cuba formed its own civil government and gained independence on May 20, 1902, with the announced end of U.S. military government jurisdiction over the island. However, the U.S. imposed various restrictions on the new government, including prohibiting alliances with other countries, and reserved the right to intervene. The U.S. also established a de facto perpetual lease of Guantánamo Bay.[171][172][173]

Remove ads

Medical disaster

Summarize

Perspective

The Spanish–American War was a medical disaster for American and Spanish forces. While combat casualties were low, disease took a devastating toll on American troops. The central medical crisis of the war was the typhoid fever epidemic that ravaged military camps. The war exposed serious deficiencies in American military medical preparedness and sanitation practices and led to long-term reforms.[174][175]

Typhoid fever

- 21,738 soldiers contracted typhoid fever (82% of all sick soldiers).

- 1,590 died from typhoid, resulting in a 7.7% mortality rate

- Typhoid accounted for 87% of all deaths from disease in assembly camps

- The epidemic affected every regiment. The assembly camps at home proved more deadly than the Cuban battlefields due to poor sanitation and inadequate medical knowledge about disease transmission.[176]

While typhoid was the primary killer, other diseases also plagued American forces. Yellow fever struck over 2,000 troops during the Cuban campaign. Malaria and dysentery were widespread among soldiers. About 55,000 Spanish troops in Cuba (out of 230,000) were incapacitated by illness.[177]

Causes

Multiple interacting factors contributed to the disaster:[178]

Lack of preparedness: Many medical officers lacked experience in camp sanitation and disease prevention. The previous Army experience in numerous small frontier camps left it unprepared. Poor sanitation: Camps were often filthy, with inadequate waste disposal systems. Insufficient medical supplies: Chaos during embarkation left many units without proper medical equipment. Inexperience: Many volunteer regiments were hastily organized, leading to increased sickness early on.

Long term impact

The medical crisis of the Spanish–American War had far-reaching consequences:[179] More soldiers died from disease than from combat (fewer than 400 killed in action vs. thousands from illness) This led to significant reforms in military medicine and sanitation practices. Special boards, such as the U.S. Army Typhoid Board, were established to study the outbreaks and recommend preventive measures.[180][181][182]

Remove ads

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

The war lasted 16 weeks. John Hay (the U.S. ambassador in London) boasted that it had been "a splendid little war".[183] The press showed Northerners and Southerners, blacks and whites fighting against a common foe, helping to ease the scars left from the American Civil War.[184] Exemplary of this was that four former Confederate States Army generals had served in the war, now in the U.S. Army and all of them again carrying similar ranks. These officers were Matthew Butler, Fitzhugh Lee, Thomas L. Rosser and Joseph Wheeler, though only the latter had seen action. Still, in an exciting moment during the Battle of San Juan Hill, Wheeler apparently forgot for a moment which war he was fighting, having supposedly called out "Let's go, boys! We've got the damn Yankees on the run again!"[185]

The war marked American entry into world affairs. Since then, the U.S. has had a significant hand in various conflicts around the world, and entered many treaties and agreements. The Panic of 1893 was over by this point, and the U.S. entered a long and prosperous period of economic and population growth, and technological innovation that lasted through the 1920s.[186]

The war redefined national identity, served as a solution of sorts to the social divisions plaguing the American mind, and provided a model for all future news reporting.[187]

The idea of American imperialism changed in the public's mind after the short and successful Spanish–American War. Because of the United States' powerful influence diplomatically and militarily, Cuba's status after the war relied heavily upon American actions. Two major developments emerged from the Spanish–American War: one, it firmly established the United States' vision of itself as a "defender of democracy" and as a major world power, and two, it had severe implications for Cuba–United States relations in the future. As historian Louis Pérez argued in his book Cuba in the American Imagination: Metaphor and the Imperial Ethos, the Spanish–American War of 1898 "fixed permanently how Americans came to think of themselves: a righteous people given to the service of righteous purpose".[188]

The 1898 war marks a turning point in American foreign relations, where the aftermath saw a change of policy away from an isolationist country to one that was willing to engage with European powers and their empires. Some historians have argued that that annexing the territories from Spain following the war, including the Philippines and Guam, suggests the US taking on a more varied foreign policy afterwards, and that the US used these as a foothold to rival the emerging German and Japanese empires interested in East Asian resources.[189] Also saying the aftermath of changes to US foreign policy, producing a more aggressive role in its relations with other countries culminated later with US involvement in the Chinese Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Aftermath in Spain

Described as absurd and useless by much of historiography, the war against the United States was sustained by an internal logic, in the idea that it was not possible to maintain the monarchical regime if it was not from a more than predictable military defeat

— Suárez Cortina, La España Liberal, [190]

A similar point of view that is shared by Carlos Dardé:

Once the war was raised, the Spanish government believed that it had no other solution than to fight, and lose. They thought that defeat —certain— was preferable to revolution —also certain—. [...] Granting independence to Cuba, without being defeated militarily... it would have implied in Spain, more than likely, a military coup d'état with broad popular support, and the fall of the monarchy; that is, the revolution

— La Restauración, 1875–1902. Alfonso XII y la regencia de María Cristina, [191]

As the head of the Spanish delegation to the Paris peace negotiations, the liberal Eugenio Montero Ríos, said: "Everything has been lost, except the Monarchy". Or as the U.S. ambassador in Madrid said: the politicians of the dynastic parties preferred "the odds of a war, with the certainty of losing Cuba, to the dethronement of the monarchy".[192] There were Spanish officers in Cuba who expressed "the conviction that the government of Madrid had the deliberate intention that the squadron be destroyed as soon as possible, in order to quickly reach peace[193]".

Although there was nothing exceptional about the defeat in the context of the time (Fachoda incident, 1890 British Ultimatum, First Italo-Ethiopian War, Greco-Turkish War (1897), Century of humiliation, Russo-Japanese War ... among other examples), in Spain the result of the war caused a national trauma due to the affinity of peninsular Spaniards with Cuba, but only in the intellectual class (which gave rise to Regenerationism and the Generation of '98), because the majority of the population was illiterate and lived under the regime of caciquismo.

The war greatly reduced the Spanish Empire. Spain had been declining as an imperial power since the early 19th century as a result of Napoleon's invasion. Spain retained only a handful of overseas holdings: Spanish West Africa (Spanish Sahara), Spanish Guinea, Spanish Morocco, and the Canary Islands. With the loss of the Philippines, Spain's remaining Pacific possessions in the Caroline Islands and Mariana Islands became untenable and were sold to Germany[194] in the German–Spanish Treaty (1899).

The Spanish soldier Julio Cervera Baviera, who served in the Puerto Rican campaign, published a pamphlet in which he blamed the natives of that colony for its occupation by the Americans, saying, "I have never seen such a servile, ungrateful country [i.e., Puerto Rico] ... In twenty-four hours, the people of Puerto Rico went from being fervently Spanish to enthusiastically American.... They humiliated themselves, giving in to the invader as the slave bows to the powerful lord."[195] He was purportedly challenged to a duel by a group of young Puerto Ricans for writing this pamphlet.[196]

Culturally, a new wave called the Generation of '98 originated as a response to this trauma, marking a renaissance in Spanish culture. Economically, the war benefited Spain, because after the war large sums of capital held by Spaniards in Cuba and the United States were returned to the peninsula and invested in Spain. This massive flow of capital (equivalent to 25% of the gross domestic product of one year) helped to develop the large modern firms in Spain in the steel, chemical, financial, mechanical, textile, shipyard, and electrical power industries.[197] However, the political consequences were serious. The defeat in the war began the weakening of the fragile political stability that had been established earlier by the rule of Alfonso XII.

A few years after the war, during the reign of Alfonso XIII, Spain improved its commercial position and maintained close relations with the United States, which led to the signing of commercial treaties between the two countries in 1902, 1906 and 1910. Spain would turn its attention to its possessions in Africa (especially northern Morocco, Spanish Sahara and Spanish Guinea) and would begin to rehabilitate itself internationally after the Algeciras Conference of 1906.[198] In 1907, it signed a kind of defensive alliance with France and the United Kingdom, known as the Pact of Cartagena in case of war against the Triple Alliance.[199] Spain improved economically because of its neutrality in the First World War.[200]

Teller and Platt Amendments

The Teller Amendment was passed in the Senate on April 19, 1898, with a vote of 42 for versus 35 against. On April 20, it was passed by the House of Representatives with a vote of 311 for versus 6 against and signed into law by President William McKinley.[201] Effectively, it was a promise from the United States to the Cuban people that it was not declaring war to annex Cuba, but would help in gaining its independence from Spain. The Platt Amendment, was a move by the United States' government to shape Cuban affairs to promote American interests without violating the Teller Amendment.[202]

The Platt Amendment granted the United States the right to stabilize Cuba militarily as needed.[203] It permitted the United States to deploy Marines to Cuba if Cuban freedom and independence were ever threatened or jeopardized by an external or internal force.[203] Passed as a rider to an Army appropriations bill which was signed into law on 2 March 1903, it effectively prohibited Cuba from signing treaties with other nations or contracting a public debt. It also provided for a permanent American naval base in Cuba.[203] Guantánamo Bay was established after the signing of the Cuban–American Treaty of Relations in 1903. The U.S. compelled Cuban assent by insinuating American forces would not be withdrawn otherwise.[citation needed] Thus, despite that Cuba technically gained its independence after the war ended, the United States government ensured that it had some form of power and control over Cuban affairs.[original research?]

Aftermath in the United States

The U.S. annexed the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.[203] The notion of the United States as an imperial power, with colonies, was hotly debated domestically with President McKinley and the Pro-Imperialists winning their way over vocal opposition led by Democrat William Jennings Bryan,[203] who had supported the war. The American public largely supported the possession of colonies, but there were many outspoken critics such as Mark Twain, who wrote The War Prayer in protest. Roosevelt returned to the United States a war hero,[203] and he was soon elected governor of New York and then became the vice president. At the age of 42, he became the youngest person to become president after the assassination of President McKinley.

The war served to further repair relations between the American North and South. The war gave both sides a common enemy for the first time since the end of the Civil War in 1865, and many friendships were formed between soldiers of northern and southern states during their tours of duty. This was an important development, since many soldiers in this war were the children of Civil War veterans on both sides.[204]

The African American community strongly supported the rebels in Cuba, supported entry into the war, and gained prestige from their wartime performance in the Army. Spokesmen noted that 33 African American seamen had died in the Maine explosion. The most influential Black leader, Booker T. Washington, argued that his race was ready to fight. War offered them a chance "to render service to our country that no other race can", because, "unlike Whites", they were "accustomed" to the "peculiar and dangerous climate" of Cuba. One of the Black units that served in the war was the 9th Cavalry Regiment. In March 1898, Washington promised the Secretary of the Navy that war would be answered by "at least ten thousand loyal, brave, strong black men in the south who crave an opportunity to show their loyalty to our land, and would gladly take this method of showing their gratitude for the lives laid down, and the sacrifices made, that Blacks might have their freedom and rights."[205]

Veterans Associations

In 1904, the United Spanish War Veterans was created from smaller groups of the veterans of the Spanish–American War. The organization has been defunct since 1992 when its last surviving member Nathan E. Cook a veteran of the Philippine-American war died, but it left an heir in the Sons of Spanish–American War Veterans, created in 1937 at the 39th National Encampment of the United Spanish War Veterans.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States (VFW) was formed in 1914 from the merger of two veterans organizations which both arose in 1899: the American Veterans of Foreign Service and the National Society of the Army of the Philippines.[206] The former was formed for veterans of the Spanish–American War, while the latter was formed for veterans of the Philippine–American War. Both organizations were formed in response to the general neglect veterans returning from the war experienced at the hands of the government.

To pay the costs of the war, Congress passed an excise tax on long-distance phone service.[207] At the time, it affected only wealthy Americans who owned telephones. However, the Congress neglected to repeal the tax after the war ended four months later. The tax remained in place for over 100 years until, on August 1, 2006, it was announced that the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS would no longer collect it.[208]

Impact on the Marine Corps

The U.S. Marine Corps during the 18th and 19th centuries was primarily a ship-borne force. Marines were assigned to naval vessels to protect the ship's crew during close quarters combat, man secondary batteries, and provide landing parties when the ship's captain needed them.[209] During the Mexican–American War and the Civil War, the Marine Corps participated in some amphibious landings and had limited coordination with the Army and Navy in their operations.[210] During the Spanish–American War though, the Marines conducted several successful combined operations with both the Army and the Navy. Marine forces helped in the Army-led assault on Santiago and Marines also supported the Navy's operations by securing the entrance to Guantanamo Bay so American vessels could clear the harbor of mines and use it as a refueling station without fear of Spanish harassment.[211] Doctrinally, the Army and the Navy did not agree on much of anything and Navy officers were often frustrated by the lack of Army support.[212] Having the Marine Corps alleviated some of this conflict because it gave Navy commanders a force "always under the direction of the senior naval officer" without any "conflict of authority" with the Army.[212]

The combined Marine Corps-Navy operations during the war also signaled the future relationship between the two services.[209] During the Banana Wars of the early 20th century, the island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific during World War II, and into modern conflicts America is involved in, the Marine Corps and Navy operate as a team to secure American interests. Thanks to the new territorial acquisitions of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, America needed the capabilities the Marines could provide.[209] The Spanish–American War was also the first time that the Marine Corps acted as America's "force in readiness" because they were the first American force to land on Cuba. Being a "body of troops which can be quickly mobilized and sent on board transports, fully equipped for service ashore and afloat" became the Marine Corps' mission throughout the rest of the 20th century and into the 21st century.[212]

The Spanish–American War also served as a coming of age for several influential Marines. Lieutenants Smedley D. Butler, John A. Lejeune, and Wendell C. Neville and Captain George F. Elliott all served with distinction with the First Battalion that fought in Cuba.[131] Lieutenant Butler would go on to earn two Medals of Honor, in Veracruz and Haiti. Lieutenants Lejeune and Neville and Captain Elliott would all become Commandants of the Marine Corps, the highest rank in the service and the leader of the entire Corps.

Marines' actions during the Spanish–American War also provided significant positive press for the Corps.[209] The men of the First Battalion were welcomed as heroes when they returned to the States and many stories were published by journalists attached to the unit about their bravery during the Battle of Guantanamo. The Marine Corps began to be regarded as America's premier fighting force thanks in large part to the actions of Marines during the Spanish–American War and to the reporters who covered their exploits.[209] The success of the Marines also led to increased funding for the Corps from Congress during a time that many high-placed Navy officials were questioning the efficacy and necessity of the Marine Corps.[212] This battle for Congressional funding and support would continue until the National Security Act of 1947, but Marine actions at Guantanamo and in the Philippines provided a major boost to the Corps' status.[209]

Aftermath in acquired territories

Article IX of The Treaty of Paris stated that the U.S. Congress were responsible for decisions regarding the civil and political rights of the indigenous populations of the newly acquired territories of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. There was initial reluctance in Congress to set firm plans for the once-Spanish islands. The debate of whether to retain the islands or give them independence eventually became the core debating and campaigning issue of the 1900 election.[213] With McKinley's victory, Congress began to pass legislation that marked the United States' "deliberate turn toward imperialism."[214]

Puerto Rico

In 1900, Congress enacted the Foraker Act, this established that Puerto Ricans would not have U.S. citizenship, despite being under U.S. sovereignty. Instead, the Act declared that they were only "citizens of Porto Rico," and therefore, would not gain the civil, political, or constitutional rights that came with U.S. citizenship.[215] The Foraker Act also established a system of taxation. Puerto Ricans were required to pay tax to fund the imposed system of government, and goods imported from the U.S. to Puerto Rico had tariffs placed upon them.[216]

The Act implemented a new system of government in Puerto Rico, with the U.S. president holding the sole power to appoint the governor and upper legislative chamber. Puerto Ricans were able to elect the lower legislative chamber delegates and a resident commissioner to represent them in Washington, although the latter role had restricted influence, as it was as a non-voting representative.[217] Two political parties emerged, the Republicanos, co-founded by Frederico Degetau, and the Federales. The Republicanos' politics were strongly aligned with U.S. policies especially in comparison to the Federales. Before the election took place, the Federales decided to boycott the polls, this was in response to the favouritism displayed towards the Republicanos by U.S. officials. The Republicanos were subsequently elected, with Degetau becoming resident commissioner.[217]

The treatment of Puerto Rico was considered unconstitutional by some due to the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment which declares that "persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States."[218] In response to this, a series of court cases known as the Insular Cases took place, which sought to determine if the territories acquired in the War would be given U.S. citizenship or any constitutional rights. As a result of these cases, the Doctrine of Territorial Incorporation was established. This stated that the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam would be categorised as "unincorporated" territories and would "not form part of the United States within the meaning of the Constitution."[219] This decree set a new precedent for how the U.S. government dealt with acquired territories, as they established a "colonial formula" in which they had total sovereignty over territories without been legally obligated to give rights to those they preside over.[220][221]

Guam