Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ann Dunham

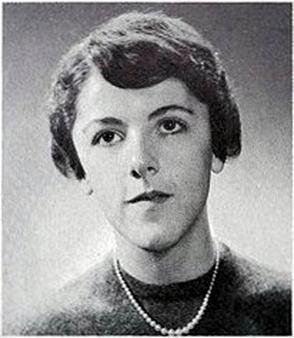

American anthropologist, mother of Barack Obama From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Stanley Ann Dunham (November 29, 1942 – November 7, 1995) was an American anthropologist who specialized in the economic anthropology and rural development of Indonesia. Born in Wichita, Kansas, she studied at the East–West Center and at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in Honolulu, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts (1967), a Master of Arts (1974), and a PhD (1992) in anthropology.

Drawing on her interest in craftsmanship, weaving, and the role of women in cottage industries, Dunham conducted research on women's work on the island of Java and blacksmithing in Indonesia. To address the problem of poverty in rural villages, she designed microcredit programs while working as a consultant for the United States Agency for International Development. In Jakarta, she worked for the Ford Foundation, and consulted for the Asian Development Bank in Pakistan. Towards the latter part of her life, she worked with Bank Rakyat Indonesia, where she helped apply her research to the largest microfinance program in the world.

As the mother of Barack Obama, the 44th president of the United States, her anthropological research faced renewed interest after his election, with new symposiums, endowments, fellowships, exhibitions, and publications dedicated to reexamining her life and upholding her legacy.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Dunham was born on November 29, 1942, in Wichita, Kansas, the only child of Madelyn Lee Payne and Stanley Armour Dunham.[1] She was of predominantly English ancestry, with small amounts of Scottish, Welsh, Irish, German and Swiss-German.[2] Wild Bill Hickok was her sixth cousin, five times removed.[3] Ancestry.com claimed on July 30, 2012, after using a combination of old documents and yDNA analysis, that Dunham's mother was descended from John Punch, an African slave in seventeenth-century colonial Virginia.[4][5]

Her parents were born in Kansas and met in Wichita, where they married on May 5, 1940.[6] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, her father joined the United States Army, and her mother worked at a Boeing plant in Wichita.[7] According to Dunham, she was named after her father because he wanted a son, though her relatives doubt this story. Her maternal uncle recalled that her mother named Dunham after her favorite actress Bette Davis' character (Stanley Timberlake) in the film In This Our Life because she thought Stanley, as a girl's name, sounded sophisticated.[1] As a child and teenager, she was known as Stanley.[8] Other children teased her about her name. Nonetheless, she used it through high school, "apologizing for it each time she introduced herself in a new town."[9] By the time Dunham began attending college, she was known by her middle name, Ann, instead.[8]

After World War II, Dunham's family moved from Wichita to California while her father attended the University of California, Berkeley. In 1948, they moved to Ponca City, Oklahoma, and from there to Vernon, Texas, and then to El Dorado, Kansas.[10] In 1955, the family moved to Seattle, Washington, where her father was employed as a furniture salesman and her mother worked as vice president of a bank. They lived in an apartment complex in the Wedgwood neighborhood where she attended Nathan Eckstein Junior High School.[11]

In 1957, Dunham's family moved to Mercer Island, an Eastside suburb of Seattle. Dunham's parents wanted their daughter to attend the newly opened Mercer Island High School.[12] At the school, teachers Val Foubert and Jim Wichterman taught the importance of challenging social norms and questioning authority to the young Dunham, and she took the lessons to heart: "She felt she didn't need to date or marry or have children." One classmate remembered her as "intellectually way more mature than we were and a little bit ahead of her time, in an off-center way",[12] and a high school friend described her as knowledgeable and progressive: "If you were concerned about something going wrong in the world, Stanley would know about it first. We were liberals before we knew what liberals were." Another called her "the original feminist".[12] She went through high school "reading beatnik poets and French existentialists".[13]

Remove ads

Family life and marriages

Summarize

Perspective

On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state to be admitted into the Union. Dunham's parents sought business opportunities in the new state, and after graduating from high school in 1960, Dunham and her family moved to Honolulu. Dunham enrolled at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa.[14][15]

First marriage

While attending a Russian language class, Dunham met Barack Obama Sr., the school's first African student.[14][15] Dunham and Obama Sr. were married on the Hawaiian island of Maui on February 2, 1961, despite parental opposition from both families.[12][16] Dunham was three months pregnant.[12][9] Obama Sr. eventually informed Dunham about his first marriage in Kenya but claimed he was divorced. Years later she discovered this was false.[15] Obama Sr.'s first wife, Kezia, later said she had granted her consent for him to marry a second wife in keeping with Luo customs.[17]

On August 4, 1961, at the age of 18, Dunham gave birth to her first child, Barack Obama, in Honolulu.[18] Friends in the state of Washington recall her visiting with her month-old baby in 1961.[19][20][21][22][23] She studied at the University of Washington from September 1961 to June 1962, and lived as a single mother in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle with her son while her husband continued his studies in Hawaii.[11][20][24][25] When Obama Sr. graduated from the University of Hawaii in June 1962,[26] he left for Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he began graduate study at Harvard University in fall 1962.[15] Dunham returned to Honolulu and resumed her undergraduate education at the University of Hawaii with the spring semester in January 1963. During this time, her parents helped her raise her child. Dunham filed for divorce in January 1964 and Obama Sr. did not contest.[9]

Second marriage

At the East–West Center, Dunham met Lolo Soetoro,[27] a Javanese[28] surveyor who came to Honolulu in September 1962. In 1965, Soetoro and Dunham were married in Hawaii, and in 1966, Soetoro returned to Indonesia. Dunham graduated from the University of Hawaii with a B.A. in anthropology on August 6, 1967, and moved in October the same year with her son to Jakarta, Indonesia, to rejoin her husband.[29]

The family first lived in a newly built neighborhood in the Menteng Dalam administrative village of the Tebet subdistrict in South Jakarta for two and a half years. In 1970 they moved to the Matraman Dalam neighborhood in the Pegangsaan administrative village of the Menteng subdistrict in Central Jakarta.[30][31] On August 15, 1970, Soetoro and Dunham had a daughter, Maya Kassandra Soetoro.[6] Dunham enriched her son's education with correspondence courses in English, recordings of Mahalia Jackson, and speeches by Martin Luther King Jr. In 1971, she sent Obama back to Hawaii to attend Punahou School.[29] In August 1972, Dunham and her daughter moved back to Hawaii so Dunham could begin graduate study in anthropology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Dunham's graduate work was supported by an Asia Foundation grant from August 1972 to July 1973 and by an East–West Center Technology and Development Institute grant from August 1973 to December 1978.[32]

Dunham completed her coursework at the University of Hawaii for an M.A. in anthropology in December 1974.[28] She spent three years in Hawaii, then returned to Indonesia in 1975 with her daughter to do anthropological field work.[32][33] Lolo Soetoro and Dunham divorced on November 5, 1980; Lolo Soetoro married Erna Kustina in 1980 and had two children, a son, Yusuf Aji Soetoro (born 1981), and daughter, Rahayu Nurmaida Soetoro (born 1987).[34] Dunham was not estranged from either ex-husband and encouraged her children to feel connected to their fathers.[35]

Remove ads

Professional life

Summarize

Perspective

Early career (1968–1975)

Dunham taught English in Central Jakarta from 1968 to 1972. She was also assistant director of the Indonesia-America Friendship Institute[32] and later a department head and director of the Institute of Management Education and Development.[32] During this same time, Dunham co-founded the Ganesha Volunteers (Indonesian Heritage Society) at the National Museum in Jakarta.[32][36] She was also a crafts instructor in weaving, batik, and dye at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu from 1972 to 1975.[32]

Development (1977–1984)

She worked in rural development, championing women's work and microcredit for the world's poor with leaders from organizations supporting Indonesian human rights, women's rights, and grass-roots development.[29] In March 1977, under the supervision of agricultural economics professor Leon A. Mears, she developed and taught a short lecture course at the Faculty of Economics of the University of Indonesia (FEUI) in Jakarta for staff members of the Indonesian National Development Planning Agency.[32]

She was a short-term consultant in the office of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Jakarta, writing recommendations on village industries and other non-agricultural enterprises for the Indonesian government's third five-year development plan (REPELITA III) between May and June 1978.[32][37] Dunham worked as a rural industries consultant in Central Java on the Indonesian Ministry of Industry's Provincial Development Program (PDP I) from October 1978 to December 1980. The program was funded by the USAID and implemented through Development Alternatives, Inc. (DAI).[32][37]

Dunham was the program officer for women and employment in the Ford Foundation's Southeast Asia regional office in Jakarta from January 1981 to November 1984.[32][37] While at the Ford Foundation, she developed a model of microfinance which is now the standard in Indonesia, a country that is a world leader in micro-credit systems.[38] Peter Geithner, father of Tim Geithner (who later became U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in her son's administration), was head of the foundation's Asia grant-making at that time.[39]

International consulting (1986–1995)

From May to November 1986 and from August to November 1987, Dunham was a cottage industries development consultant for the Agricultural Development Bank of Pakistan (ADBP) under the Gujranwala Integrated Rural Development Project (GADP).[32][37] The credit component of the project was implemented in the Gujranwala district of the Punjab province of Pakistan with funding from the Asian Development Bank and IFAD, with the credit component implemented through Louis Berger International, Inc.[32][37] Dunham worked closely with the Lahore office of the Punjab Small Industries Corporation (PSIC).[32][37]

From January 1988 to 1995, Dunham was a consultant and research coordinator for Indonesia's oldest bank, Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) in Jakarta, with her work funded by USAID and the World Bank.[32][37] In March 1993, Dunham was a research and policy coordinator for Women's World Banking (WWB) in New York.[32] She helped WWB manage the Expert Group Meeting on Women and Finance in New York in January 1994, and helped the WWB take prominent roles in the UN's Fourth World Conference on Women held September 4–15, 1995 in Beijing, and in the UN regional conferences and NGO forums that preceded it.[32]

Remove ads

Academic research

Summarize

Perspective

Dunham carried out research on village industries in the Yogyakarta Special Region within Central Java in Indonesia under a student grant from the East–West Center from June 1977 through September 1978.[37] As a weaver herself, Dunham was interested in village industries, and moved to Yogyakarta City, the center of Javanese handicrafts.[33][40]

Dunham was awarded a PhD in anthropology from the University of Hawaii on August 9, 1992. Her 1,043-page dissertation was completed under the supervision of Alice G. Dewey.[41] Titled Peasant blacksmithing in Indonesia: Surviving against all odds,[42] it was described by anthropologist Michael Dove as "a classic, in-depth, on-the-ground anthropological study of a 1,200-year-old industry".[43] According to Dove, Dunham's dissertation challenged popular perceptions regarding economically and politically marginalized groups, and countered the notions that the roots of poverty lie with the poor themselves and that cultural differences are responsible for the gap between less-developed countries and the industrialized West.[43]

Duke University Press published a new version of Dunham's dissertation as a book in December 2009. It was revised and edited by Dunham's graduate advisor Alice G. Dewey and Nancy I. Cooper, with a foreword by Dunham's daughter, Maya Soetoro-Ng. In his afterword, Boston University anthropologist Robert W. Hefner describes Dunham's research as "prescient" and her legacy as "relevant today for anthropology, Indonesian studies, and engaged scholarship".[44] The book was launched at the 2009 annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association in Philadelphia with a special Presidential Panel on Dunham's work; the 2009 meeting was taped by C-SPAN.[45]

Dunham produced a large amount of professional papers that are held in collections of the National Anthropological Archives (NAA). Her daughter donated a collection of them that is categorized as the S. Ann Dunham papers, 1965–2013. This collection contains case studies, correspondence, field notebooks, lectures, photographs, reports, research files, research proposals, surveys, and floppy disks documenting her dissertation research on blacksmithing, as well as her professional work as a consultant for organizations such as the Ford Foundation and the Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI). They are housed at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Her field notes have been digitized and, in 2020, Smithsonian Magazine noted that an effort had been established for a project to transcribe them.[46]

Remove ads

Illness and death

Summarize

Perspective

In late 1994, Dunham was living and working in Indonesia. One night, during dinner at a friend's house in Jakarta, she experienced stomach pain. A visit to a local physician led to an initial diagnosis of indigestion.[9] Dunham returned to the United States in early 1995 and was examined at the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center in New York City and diagnosed with uterine cancer. By this time, the cancer had spread to her ovaries.[15] She moved back to Hawaii to live near her widowed mother and died on November 7, 1995, 22 days short of her 53rd birthday.[47][48][29][49][50] Following a memorial service at the University of Hawaii, Obama and his sister spread their mother's ashes in the Pacific Ocean at Lanai Lookout on the south side of Oahu.[29] Obama scattered the ashes of his grandmother Madelyn Dunham in the same spot on December 23, 2008, weeks after his election to the presidency.[51]

Obama talked about Dunham's death in a 30-second campaign advertisement ("Mother") arguing for health care reform. The ad featured a photograph of Dunham holding a young Obama in her arms as Obama talks about her last days worrying about expensive medical bills.[50] The topic also came up in a 2007 speech in Santa Barbara.[50] Dunham's employer-provided health insurance covered most of the costs of her medical treatment, leaving her to pay the deductible and uncovered expenses, which came to several hundred dollars per month. Her employer-provided disability insurance denied her claims for uncovered expenses because the insurance company said her cancer was a preexisting condition.[52][53]

Remove ads

Personal beliefs

Summarize

Perspective

She felt that somehow, wandering through uncharted territory, we might stumble upon something that will, in an instant, seem to represent who we are at the core. That was very much her philosophy of life — to not be limited by fear or narrow definitions, to not build walls around ourselves and to do our best to find kinship and beauty in unexpected places.

Maya Soetoro-Ng[29]

In his 1995 memoir Dreams from My Father, Barack Obama wrote, "My mother's confidence in needlepoint virtues depended on a faith I didn't possess... In a land [Indonesia] where fatalism remained a necessary tool for enduring hardship ... she was a lonely witness for secular humanism, a soldier for New Deal, Peace Corps, position-paper liberalism."[54] In his 2006 book The Audacity of Hope Obama wrote, "I was not raised in a religious household ... My mother's own experiences ... only reinforced this inherited skepticism. Her memories of the Christians who populated her youth were not fond ones ... And yet for all her professed secularism, my mother was in many ways the most spiritually awakened person that I've ever known."[55] "Religion for her was "just one of the many ways—and not necessarily the best way—that man attempted to control the unknowable and understand the deeper truths about our lives," Obama wrote.[56]

Maxine Box, Dunham's best friend in high school, recalled that Dunham openly identified as an atheist and was intellectually engaged with the topic and other subjects well in advance of her peers.[12][57] On the other hand, Dunham's daughter, Maya Soetoro-Ng, when asked later if her mother was an atheist, said, "I wouldn't have called her an atheist. She was an agnostic. She basically gave us all the good books—the Bible, the Hindu Upanishads and the Buddhist scripture, the Tao Te Ching—and wanted us to recognize that everyone has something beautiful to contribute."[27] "Jesus, she felt, was a wonderful example. But she felt that a lot of Christians behaved in un-Christian ways."[56]

In a 2007 speech, Obama contrasted the beliefs of his mother to those of her parents, and commented both on her spirituality and her skepticism.[9] He described his mother's parents as coming from a Baptist and Methodist background in a culture that was nonobservant and skeptical of organized religion. Obama, who identifies as a Christian, also had a father from a Kenyan Muslim family who was not religious and did not practice Islam.[58]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

The University of Hawaii at Mānoa (UH) first held a symposium about Dunham in September 2008.[59] The University of Hawaii Foundation established the Ann Dunham Soetoro Endowment, which supports a faculty position housed in the Anthropology Department at UH, and the Ann Dunham Soetoro Graduate Fellowships, which provide funding for students associated with the East–West Center (EWC).[60] Dunham's alma mater, Mercer Island High School, began offering the Stanley Ann Dunham Scholarship in 2010.[61] President Obama and his family visited an exhibition of his mother's anthropological work on display at the EWC in 2012.[62]

An exhibition of Dunham's Javanese batik textile collection (A Lady Found a Culture in its Cloth: Barack Obama's Mother and Indonesian Batiks) toured six museums in the United States, finishing the tour at the Textile Museum of Washington, D.C., in August 2009.[63] Earlier in her life, Dunham was interested in the textile arts as a weaver, creating wall hangings for her own enjoyment. After moving to Indonesia, she was attracted to the striking textile art of the batik and began to collect a variety of different fabrics.[64] Dunham was awarded the Bintang Jasa Utama, Indonesia's highest civilian award, in December 2010; the Bintang Jasa is awarded at three levels, and is presented to those individuals who have made notable civic and cultural contributions.[65]

A major biography of Dunham by former New York Times reporter Janny Scott, titled A Singular Woman, was published in 2011.[66] Filmmaker Vivian Norris's feature length biographical film of Ann Dunham entitled Obama Mama (La mère d'Obama-French title) premiered on May 31, 2014, as part of the 40th annual Seattle International Film Festival, not far from where Dunham grew up on Mercer Island.[67] In the 2016 film Barry, a dramatization of Barack Obama's life as an undergraduate college student, Dunham is played by Ashley Judd.[68]

Remove ads

Publications

- Dunham, S Ann (1982). Civil rights of working Indonesian women. OCLC 428080409.

- Dunham, S Ann (1982). The effects of industrialization on women workers in Indonesia. OCLC 428078083.

- Dunham, S Ann (1982). Women's work in village industries on Java. OCLC 663711102.

- Dunham, S Ann (1983). Women's economic activities in North Coast fishing communities: background for a proposal from PPA. OCLC 428080414.

- Dunham, S Ann; Haryanto, Roes (1990). BRI Briefing Booklet: KUPEDES Development Impact Survey. Jakarta: Bank Rakyat Indonesia.

- Dunham, S Ann (1992). Peasant blacksmithing in Indonesia : surviving against all odds (PhD thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. OCLC 608906279, 607863728, 221709485. ProQuest 304001600.

- Dunham, S Ann; Liputo, Yuliani; Prabantoro, Andityas (2008). Pendekar-pendekar besi Nusantara : kajian antropologi tentang pandai besi tradisional di Indonesia [Nusantara iron warriors: an anthropological study of traditional blacksmiths in Indonesia] (in Indonesian). Bandung, Indonesia: Mizan. ISBN 9789794335345. OCLC 778260082.

- Dunham, S Ann (2010) [2009]. Dewey, Alice G; Cooper, Nancy I (eds.). Surviving against the odds : village industry in Indonesia. Foreword by Maya Soetoro-Ng; afterword by Robert W. Hefner. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822346876. OCLC 492379459, 652066335.

- Dunham, S Ann; Ghildyal, Anita (2012). Ann Dunham's legacy : a collection of Indonesian batik. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. ISBN 9789834469672. OCLC 809731662.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads