Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Tekhelet

Blue dye prized by ancient Mediterranean civilizations From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Tekhelet[a] (Hebrew: תְּכֵלֶת təḵēleṯ) is a blue dye that historically held great significance in ancient Mediterranean civilizations. It is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and is accordingly commonplace in Jewish culture, wherein it features prominently to color the fringes (called tzitzit) of several Jewish religious garments, such as the tallit. The dye was similarly used in the clothing of the High Priest of Israel and in tapestries in the Tabernacle.[1]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Biblical texts do not specify the source or production method of tekhelet. Rabbinic literature, however, records that it was produced from a marine animal: ḥillāzon (חלזון).[b] The practical knowledge of tekhelet production was lost over time, resulting in the omission of the dye from tzitzit. The ḥillāzon has been identified in contemporary times as Hexaplex trunculus.

Remove ads

Biblical references

Of the 49[3] or 48[1][4] uses of the word tekhelet in the Masoretic Text, only one refers to fringes on cornered garments of the whole people of Israel (Numbers 15:37–41). Six are non-ritual uses, such as Mordechai dressing himself in tekhelet before the King of Persia (Esther 8:15). Tekhelet could be used in combination with other colors as in 2 Chronicles 3:14 where the veil of Solomon's Temple is made of tekhelet, Tyrian purple (Hebrew: אַרְגָּמָן, romanized: ʾargāmān) and scarlet (Hebrew: שָׁנִי, romanized: šāni or כַּרְמִיל karmil). Ezekiel 27:7 mentions that tekhelet-cloth could be obtained from "isles of Elishah" (Cyprus). All Biblical mentions of tekhelet imply that it was difficult to obtain and expensive, an impression corroborated by later rabbinic writings.[5]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The manufacture of tekhelet is believed to date back to 1750 BCE at least. In the Amarna letters (14th century BCE) tekhelet garments are listed as a precious good used for a royal dowry.[6]

Data about the dye seems to have been lost sometime after the period of Rav Ahai (5th–6th century).[7] The Tanhuma (8th century) is the first written source to lament this loss.[6]

In his doctoral thesis (London, 1913) on the subject, Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog proposes H. trunculus (then known as Murex trunculus) as the most likely candidate for the source of the dye.[8][9] Though H. trunculus fulfilled many of the Talmudic criteria, Herzog's inability to consistently obtain blue dye from the snail precluded him from declaring it to be the dye source.

In the 1980s, Otto Elsner, a chemist from the Shenkar College of Fibers in Israel, discovered that if a solution of the dye was exposed to ultraviolet rays such as from sunlight, blue instead of purple was consistently produced.[10][11] Elsner's discovery of that exposure to sunlight turns the red 6,6'-dibromoindigo extracted from the hypobranchial gland of H. trunculus snails[12] into a mixture of blue indigo dye and blue-purple 6-bromoindigo was widely viewed as resolving Herzog's issue.

In 1988, Rabbi Eliyahu Tavger dyed tekhelet from H. trunculus for the commandment of tzitzit for the first time in recent history.[6]: 23 Based on this work, four years later, the ''Ptil Tekhelet'' Organization (he) was founded to educate about the dye production process and to make the dye available for all who desire to use it.

Remove ads

Color

Summarize

Perspective

The exact hue of tekhelet in antiquity is not definitive. The color of tekhelet was likely to have varied in practice, as ancient dyers would have lacked the capability of producing precise shades from one batch of dye to another.[13] Modern scholars believe that tekhelet probably referred to blue to blue-purple colors.[14]

In the early classical sources (Septuagint, Aquila, Symmachus, Vulgate, Philo, and Josephus), tekhelet was translated into Koine Greek as hyakinthos (ὑακίνθος, "alpine squill"[15]) or its Latin equivalent.[16] The flower of the alpine squill ranges from a violet blue to a bluish purple, and the word hyakinthos was used to describe both blue and purple colors.[16]

Early rabbinic sources provide indications as to the nature of the color. Some sources describe tekhelet as visually indistinguishable from indigo (קלא אילן qālā ilān).[c] This description is also somewhat ambiguous, as different varieties of indigo have colors ranging between blue and purple,[16] but generally the color of dyed indigo in the ancient world was blue.[17]

Other rabbinic sources describe tekhelet as similar to the sea or sky. An oft-repeated explanation for the Torah's choice of tekhelet went as follows: "Why is tekhelet different from all other colors? Because tekhelet is similar [in appearance] to the sea, and the sea is similar to the sky, and the sky is similar to lapis lazuli, and lapis lazuli is similar to the Throne of Glory."[18] (In a few versions of this source, "plants" are included in this chain of similarity even though plants are not blue;[19] though it has been suggested that these sources refer to bluish plants like hyacinth.)[16]

In other sources, the color of the tekhelet is compared to the night sky.[20] Rashi quotes Moshe ha-Darshan who describes it as "the color of the sky as it darkens toward evening" – a deep sky blue or dark violet.[21]

Rashi himself describes the color as "green" (ירוק)[22] and "green, and close to the color of leeks",[23] the latter commenting on a Talmudic passage according to which the morning Shema may be recited once it is light enough to distinguish between tekhelet and leeks. However, other rabbinic texts comment that "the appearance which is called in the language of Ashkenaz bleu (בלו"א) is within the category of green"[24] suggesting that Rashi's language does not necessarily rule out a blue color.

The Sifrei says that counterfeit tekhelet was made from both "[red] dye and indigo", indicating that the overall color was purple.[d] However, other sources list just "indigo" as the counterfeit, suggesting either that in their opinion the color was purely blue, or that indigo was the main counterfeit ingredient and the other ingredients not significant enough to mention.

The Sippar Dye Text (7th century), as well as the Leyden papyrus X and Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis (3rd century) provide recipes for counterfeit takiltu that includes a mixture of red and blue colors, for an overall purple color.[14]

A pure blue can only be produced from Hexaplex dye through a debromination process. The creation of blue Hexaplex dye using this process was only discovered in the 1980's, leading some experts to conclude that ancient dyers would not have been able to create blue tekhelet (and, therefore, that an undebrominated purple color is more likely).[16] However, in recent years archaeologists have recovered several fabrics dyed blue with Hexaplex dye 1800 or more years ago, demonstrating that ancient dyers could and did make blue dye from Hexaplex.[17] Such fabrics have been found at Wadi Murabba'at (2nd century),[25] Masada (1st century BCE),[26] Qatna (14th century BCE),[27] and arguably[28] the Pazyryk burials (5th–4th century BCE).[17]

Remove ads

Source – Identifying the ḥillazon

Summarize

Perspective

While the Bible does not identify the source of tekhelet, rabbinic texts specified that it could only be made from a sea creature known as the ḥillāzon.[e] Various animals have been suggested as the ḥillazon.[30][31][12][32]

Rabbinic sources describe several qualities of this animal. It was found on the coast between Tyre and Haifa.[33] "Its body is similar to the sea, and its form (ברייתו) is similar to a fish, and it comes up [from the sea] once every 70 years, and with its blood tekhelet is dyed, therefore it is expensive."[34] Dye was extracted from the Ḥillazon by cracking it open, suggesting that it has a hard external shell.[35] Another source suggested that just as the Hebrews' clothing did not wear out in the desert (Deut 8:4), the shell of the ḥillāzon does not wear out.[36]

Garments dyed with tekhelet and indigo have such a similar appearance that it was said only God can distinguish them.[37] One opinion states that there is no chemical test which can distinguish between tekhelet and indigo wool, but another opinion describes such a test and tells the story of it working successfully.[38] Trapping the ḥillāzon is considered a violation of Shabbat.[39] In the time of the Talmud, the ḥillāzon was used as part of a remedy for hemorrhoids,[40] though this may refer to a different species of snail.[f]

Hexaplex trunculus

Arguments for Hexaplex trunculus

The dye produced by Hexaplex has the exact same chemical composition as indigo,[41] corresponding to the statement that only God can distinguish the tekhelet from indigo garments.

In the area between Tyre and Haifa where the ḥillāzon was found, piles of murex shells hundreds of yards long have been found, apparently the result of dyeing operations.[42] In Tel Shikmona (near Haifa), a "biblical era purple dye workshop" was found, including relics of purple dye produced from sea snails, as well as textile manufacturing equipment.[43]

Chemical testing of ancient blue-dyed cloth from the appropriate time period in Israel reveals that a sea snail-based dye was used. Since murex dye was available, very long-lasting, and visibly indistinguishable from indigo-based dyes, but also not specifically prohibited as counterfeit despite being known, it is argued that H. trunculus (or one of the other two indigo-producing sea snails) must have been the ḥillāzon or at least deemed as acceptable to use interchangeably.[44]

The word ḥillāzon is cognate to the Arabic word halazūn (حلزون), meaning snail.[45] Hexaplex opponents suggest that in ancient times the word might have referred to a broader category of animals, perhaps including other candidate species such as the cuttlefish.[46]

Another Talmudic requirement is that the dye cannot fade, and the H. trunculus dye does not fade and can only be removed from wool with bleach.[47]

The Talmud states that the ḥillāzon is preferably kept alive while the dye is extracted, as killing it causes the dye to degrade.[g] This matches both ancient descriptions of the Hexaplex dyeing process and also modern experience that an enzyme in the snail needed for dye production decays quickly after death.[42][49]

The Jerusalem Talmud as quoted by Raavyah translates tekhelet as porporin;[h] similarly Musaf Aruch translates tekhelet as parpar. These translations refer to the Latin term purpura, meaning the dye produced by Hexaplex snails.[42] Similarly, Yair Bacharach stated that tekhelet was derived from purpura snails, even though this forced him to conclude that the colour of tekhelet was purple (purpur) rather than blue, as in his era it was unknown how to produce blue dye from Hexaplex.[42][51]

The word porforin, or porpora, or porphoros is used in the midrash as well as many other Jewish texts to refer to the Ḥillazon, and this is the Greek[52] translation of Murex trunculus. Pliny and Aristotle also both refer to the Porpura as being the source for purple and blue dyes, showing that the Murex has a long history of being used for blue dye.[53]

Deuteronomy 33:19 speaks of "treasures hidden in the sand", which the Talmud clarifies refers to the ḥillāzon.[54] H. trunculus often burrows into the sand, making it difficult to detect even by scuba divers.[42]

While (as described in the next section) Hexaplex arguably does not fit every textual description of the ḥillāzon, nevertheless, "Of the thousands of fish and mollusks that were studied to date, no other fish has been found that can produce the tekhelet color", which suggests that there is no more likely alternative species.[42]

Arguments against Hexaplex trunculus

The Talmud equates the colors of tekhelet and indigo but also gives a practical test to distinguish between the two fabrics. Seemingly, since the color-producing compounds in H. trunculus and indigo are identical, no test should be able to distinguish them.[42][46] However, according to Professor Otto Elsner, while Hexaplex and indigo have the same color-producing compound, they also contain other compounds which differ and may lead to a different response in the practical test.[42] According to Dr. Israel Irving Ziderman's, heating the violet wool in 60-80C will turn the wool blue with a small hint of violet.

The ḥillāzon's body resembles the sea, which is not intuitive of H. trunculus. When alive, H. trunculus is well camouflaged and has a similar appearance to the sea floor, apparently due to algae growing on its shell.[42] The shell color can even be blue, similar to the sea.[55]

The ḥillāzon has a "form like a fish", which a snail seemingly is not. H. trunculus' shell somewhat resembles a fish in shape.[56] Similarly Maimonides, Tosafot, and Rashi say the Ḥillazon is a "fish" (דג), while H. trunculus is a snail rather than a fish. H. trunculus supporters argue that many other forms of aquatic life not usually called a "fish" (e.g., shellfish) are also called "דגים" in Hebrew.[57]

The ḥillāzon is said to come up from the sea once every 70 years. It is unclear what this is exactly referring to, but the Hexaplex has no such cycle.[46] Hexaplex supporters note that elsewhere the Talmud makes clear that the ḥillāzon was also hunted by normal methods at other times.[39] Some sources say the reference to "70 years" does not imply a periodic cycle, but rather simply that this phenomenon is a rare event.[42] Hexaplex may have cycles of other lengths which inspired this statement: a seven-month cycle for harvesting Hexaplex was claimed by Pliny and confirmed in modern research, while Hexaplex appears to have a yearly behavioral cycle in which it burrows in the sand in summer and emerges from swimming in winter.[55] Other sources claim that the 70-year cycle was a miraculous occurrence which no longer occurs or else that the decrease in Hexaplex population numbers may have caused this behavior to cease.[42]

Two other snails produce natural indigo dye like H. trunculus: Bolinus brandaris and Stramonita haemastoma. However, H. trunculus contains a higher proportion of natural indigo and thus is a more natural source for blue tekhelet. Archaeological finds show H. trunculus being processed separately from snails of the other species, suggesting that a different color was derived from this species.[49]

Trapping the Ḥillazon is a violation of Shabbat.[39] However, according to some rishonim, in general, it is permitted to capture slow-moving animals like snails on Shabbat (as capturing them requires only a trivial effort - בחד שחיא).[58] This contradiction suggests that the hillazon is not a snail. Hexaplex supporters argue that since Hexaplex tends to camouflage itself and hide in the sand, capturing it is a difficult process and thus (by some opinions) forbidden.[42] There is another point of contention in that the animals permitted to catch are land-based slow-moving creatures. All sea-based creatures, aside from having the halakhic status of a "fish", on a more practical level are impossible for the average person to gather without some form of trapping, and in fact, even today are caught with nets[59] or wicker baskets.[60]

Maimonides described the ḥillāzon, stating that "its blood is as black as ink",[61] which does not seem to match the characteristics of Hexaplex. Hexaplex supporters argue that this claim has no source earlier than Rambam and seems to be based on a mistaken statement by Aristotle[46] However, a black precipitate can indeed be derived from Hexaplex and refined into dye.[55] Additionally, Aristotle classified the dye secretions of marine snails into two color categories: black and red, with tekhelet falling under the black blood category.[62] In his "History of Animals", Aristotle writes: "There are many kinds of purpurae ... Most of them contain a black pigment; in others, it is red, and the quantity of it small."[63]

Tractate Menachot[64] and the Rambam explain the process for making the dye for tekhelet, and neither of them mention explicitly that it needs to be placed in the sunlight. Exposing the dye to sunlight is the most commonly used method today to make the dye from H. trunculus.[57] Other methods have been discovered to produce blue, such as like boil heating or adding a strong reactant.[65]

Sepia officinalis

In 1887, Grand Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner ("the Radziner Rebbe") concluded that Sepia officinalis (common cuttlefish) met many of the criteria. Within a year, Radziner chassidim began wearing tzitzit with cuttlefish dye. Herzog obtained a sample of this dye and had it chemically analyzed. The chemists concluded that it was the well-known synthetic dye "Prussian blue" made by reacting iron(II) sulfate with an organic material. In this case, the cuttlefish only supplied the organic material, which could have as easily been supplied from a vast array of organic sources. Herzog thus rejected the cuttlefish as the ḥillāzon. Some [who?] suggest that had Leiner known this fact, he too would have rejected it based on his explicit criterion that the blue color must come from the animal and that all other additives are permitted solely to aid the color in adhering to the wool.[66]

Janthina

Having failed to consistently achieve blue dye from H. trunculus, Herzog wrote, "If for the present all hope is to be abandoned of rediscovering the ḥillāzon shel tekhēleth in some species of the genera Murex [now "Hexaplex"] and Purpura we could do worse than suggest Janthina as a not improbable identification".[67] Janthina is another genus of sea snails, separate from Hexaplex. More recently, blue dye has been obtained from Janthina,[68] but Janthina seems an unsuitable candidate in several ways: it was apparently only rarely used by ancient dyers; only found far out at sea (while the ḥillāzon is apparently found near the coast); and its pigment is allegedly unsuitable for dyeing.[55]

Remove ads

Current status of the tekhelet commandment

Summarize

Perspective

A midrash states that tekhelet was "hidden" (נגנז) and now only white strings are available.[69] The meaning of the term "hidden" is unclear. Beit Halevi argued (when debating the Radziner rebbe) that a continuous tradition regarding the source of the dye, which no longer exists, was necessary in order for it to be used.[70] However, Radbaz and Maharil ruled otherwise, that rediscovering the dye is sufficient to perform the commandment.[42] Yeshuot Malko suggested that even if tekhelet was hidden until the messianic era, the apparent rediscovery of tekhelet suggests that the messianic era is approaching, rather than suggesting that the tekhelet is invalid.[71]

A principle of halakha is that when in doubt about the laws of a commandment from the Torah, one acts stringently. Some rabbis [who?], therefore, argue that even if we are uncertain in our identification of the ḥillāzon, we must wear the most likely dye anyway (i.e. Hexaplex). Others disagree, asserting that the principle of stringency only applies in cases such that after one acts stringently, there is no further obligation (whereas if Hexaplex is only doubtfully correct, there would remain a theoretical obligation to find the actual correct species and use it).[42] Nevertheless, a number of Rabbis wear tekhelet publicly.[72]

Based on Deuteronomy 14:1, the Talmud rules that we should not make divisions among the Jewish people. Therefore, if a person acts differently from the rest of the Jewish people, they are creating divisions.[73] Some have argued that one should not publicly wear tekhelet for this reason;[74] others consider this not to be a concern.[75] In any case it would not be relevant in many contemporary communities where tekhelet-wearing is widespread.

There exists a Torah commandment not to detract from any other law. Rabbi Hershel Schachter says that if one knows what tekhelet is, yet chooses to wear tzitzit without tekhelet, they are violating this commandment.[76] Many other rabbis do not agree with this statement.

Remove ads

Tying methods

Summarize

Perspective

A garment with tzitzit consists of four tassels, each containing four strings. There are three differing opinions in rabbinic literature regarding the number of strings in each tassel that should be dyed with tekhelet: two strings,[77] one string,[78] or one-half string.[79]

Maimonides holds that half of one string should be colored blue, and it should wrap around the other seven white strings. It should wrap around three times and then leave some space and then three more and leave some more space and should continue like this for either 7 or 13 groups. The first and last wrap-around should be from a white string, not a blue string.[80]

Abraham ben David holds that one full string should be blue, and there should be four groups of at least seven coils alternating between white and blue, both beginning and ending with blue.[80] There are multiple other opinions of how to tie the tzitzit if one full string is blue.

Tosafot holds that two full strings should be tekhelet. He is of the opinion that the coils should be in groups of three, starting with three white, then three blue alternating and ending with three white.[81] There is another way to tie using two full strings that Rabbi Hershel Schachter follows based on the opinion of Samuel ben Hofni.[80]

Remove ads

Tekhelet in Jewish culture

Besides the ritual uses of tekhelet, the color blue plays various roles in Jewish culture, largely influenced by the role of tekhelet.

The stripes on the tallit, often black or blue, are believed by some to symbolize the lost tekhelet,[82] though other explanations have been given.[16] The use of blue in the tallit and temple robes led to the association of blue and white with Judaism[83] and inspired the design of the flag of Israel.

Like their non-Jewish neighbors, Jews of the Middle East painted their doorposts, and other parts of their homes with blue dyes; have ornamented their children with tekhelet ribbons and markings.[84]

Remove ads

Gallery

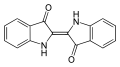

- Structural formula of murex-based tyrian purple, the red-purple dye present in tekhelet indigo before exposure to sunlight. (note the two bromides: in marine environments, sodium bromide is abundant. It is far less abundant in terrestrial environments[citation needed])

- Structural formula of plant based or synthetic indigo, a counterfeit dark-blue

See also

- Argaman, also called Tyrian purple, a Biblical reddish-purple dye from the related seasnail, Bolinus brandaris

Note

- Also transliterated as tekheleth, t'chelet, techelet, and techeiles.

- Bava Metzia 61a-b; Menachot 40a-b

- "Sifrei Bamidbar 115:1". www.sefaria.org.

- Unusually, Rabbi Israel Lipschitz wrote that any dye of the proper color could serve as tekhelet, not just ḥillāzon dye.[29]

- The term hillāzon does not refer exclusive to the animal from which tekhelet was derived; for example, in tractate Sanhedrin 91a it refers to a land snail.

- Note that this wording is not present in contemporary texts of the Jerusalem Talmud. According to Raavyah, the Jerusalem Talmud text is בין תכלת לכרתן, בין פורפרין ובין פריסינן, with פריסינן meaning "leek" similar to πράσο in modern Greek. Thus, the Jerusalem Talmud is simply translating "tekhelet" and "leek" to their Greek equivalents. This interpretation follows a recently discovered manuscript of Raavyah's commentary; previously, printed editions of the commentary had substituted פריפינין for פריסינן (an apparent corruption, though justified by the creative suggestion[46] that it represents a novel Greek word parufaino, meaning "a robe with a hem or border of purple").[50]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads