Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Third party (U.S. politics)

US political parties other than the two major parties From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Third party, or minor party, is a term used in the United States' two-party system for political parties other than the Republican and Democratic parties. The plurality voting system for presidential and Congressional elections have over time helped establish a two-party system in American politics. Third parties are most often encountered in presidential nominations and while third-party candidates rarely win elections, they can have an effect on them through vote splitting and other impacts.

James B. Weaver won five states in 1892.

Robert M. La Follette won his home state of Wisconsin in 1924.

Strom Thurmond won four states in 1948.

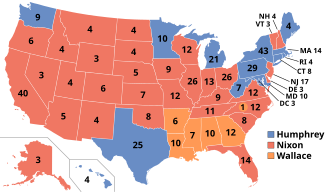

George Wallace won five states in 1968.

With few exceptions,[1] the U.S. system has two major parties which have won, on average, 98% of all state and federal seats.[2] According to Duverger's law two main political parties emerge in political systems with plurality voting in single-member districts. In this case, votes for minor parties can potentially be regarded splitting votes away from the most similar major party.[2][3] Third party vote splitting exceeded a president's margin of victory in three elections: 1844, 2000, and 2016.

There have only been a few rare elections where a minor party was competitive with the major parties, occasionally replacing one of the major parties in the 19th century.[3][4] No third-party candidate has won the presidency since the Republican Party became the second major party in 1856. Since then, a third-party candidate won states in five elections: 1892, 1912, 1924, 1948, and 1968. 1992 was the last time a third-party candidate placed second in any state, and 1996 was the last time a third-party candidate got over 5% of the vote nationally.[5]

Remove ads

Notable exceptions

Summarize

Perspective

Greens, Libertarians, and others have elected state legislators and local officials. The Socialist Party elected hundreds of local officials in 169 cities in 33 states by 1912, including Milwaukee, Wisconsin; New Haven, Connecticut; Reading, Pennsylvania; and Schenectady, New York.[6] There have been governors elected as independents, and from such parties as Progressive, Reform, Farmer-Labor, Populist, and Prohibition. After losing a Republican primary in 2010, Bill Walker of Alaska won a single term in 2013 as an independent by joining forces with the Democratic nominee. In 1998, wrestler Jesse Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota on the Reform Party ticket.[7]

Sometimes a national officeholder that is not a member of any party is elected. Previously, Senator Lisa Murkowski won re-election in 2010 as a write-in candidate after losing the Republican primary to a Tea party candidate, and Senator Joe Lieberman ran and won reelection to the Senate as an "Independent Democrat" in 2006 after losing the Democratic primary.[8][9] As of 2025, there are only two U.S. senators, Angus King and Bernie Sanders, who identify as Independent and both caucus with the Democrats.[10]

The last time a third-party candidate carried any states in a presidential race was George Wallace in 1968, while the last third-party candidate to finish runner-up or greater was former president Teddy Roosevelt's 2nd-place finish on the Bull Moose Party ticket in 1912.[5] The only three U.S. presidents without a major party affiliation upon election were George Washington, John Tyler, and Andrew Johnson, and only Washington served his entire tenure as an independent. Neither of the other two were ever elected president in their own right, both being vice presidents who ascended to office upon the death of the president, and both became independents because they were unpopular with their parties. John Tyler was elected on the Whig ticket in 1840 with William Henry Harrison, but was expelled by his own party. Johnson was the running mate for Abraham Lincoln, who was reelected on the National Union ticket in 1864; it was a temporary name for the Republican Party.

Remove ads

More favorable electoral systems for third parties

Summarize

Perspective

Electoral fusion

Electoral fusion in the United States is an arrangement where two or more United States political parties on a ballot list the same candidate,[11] allowing that candidate to receive votes on multiple party lines in the same election.[12]

Electoral fusion is also known as fusion voting, cross endorsement, multiple party nomination, multi-party nomination, plural nomination and ballot freedom.[13][14]

Electoral fusion was once widespread in the U.S. and legal in every state. However, as of 2024, it remains legal and common only in New York and Connecticut.[15][16][17]Ranked-choice voting

Some state-wide elections

Local option for municipalities to opt-in

Local elections in some jurisdictions

RCV banned state-wide

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) can refer to one of several ranked voting methods used in some cities and states in the United States. The term is not strictly defined, but most often refers to instant-runoff voting (IRV) or single transferable vote (STV), the main difference being whether only one winner or multiple winners are elected. At the federal and state level, instant runoff voting is used for congressional and presidential elections in Maine; state, congressional, and presidential general elections in Alaska; and special congressional elections in Hawaii. Since 2025, it is also used for all elections in the District of Columbia.

Single transferable voting, only possible in multi-winner contests, is not currently used in state or congressional elections. It is used to elect city councillors in Portland, Oregon, Cambridge, Mass., and several other cities.[19][20]

As of April 2025, RCV is used for local elections in 47 US cities including Salt Lake City and Seattle.[21] It has also been used by some state political parties in party-run primaries and nominating conventions.[22][23][24] As a contingency in the case of a runoff election, ranked ballots are used by overseas voters in six states.[21]

Since 2020, voters in seven states have rejected ballot initiatives that would have implemented, or allowed legislatures to implement, ranked choice voting. As of June 2025, ranked-choice voting has also been banned in seventeen states.[25][26][27]

Notwithstanding apparent efforts by RCV advocates to implement RCV in all elections, there exists much public, private, and academic hesitation as to the viability of such an undertaking. Complexity, cost, possible promotion of strategic voting, and issues of transparency are among issues cited as barriers to adoption.[28]Approval voting

Approval voting is a single-winner rated voting system where voters can approve of all the candidates as they like instead of choosing one. The method is designed to eliminate vote-splitting while keeping election administration simple and easy-to-count (requiring only a single score for each candidate). Approval voting has been used in both organizational and political elections[which?] to improve representativeness and voter satisfaction.

Critics of approval voting have argued the simple ballot format is a disadvantage, as it forces a binary choice for each candidate (instead of the expressive grades of other rated voting rules).Proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body.[29] The concept applies mainly to political divisions (political parties) among voters. The aim of such systems is that all votes cast contribute to the result so that each representative in an assembly is mandated by a roughly equal number of voters, and therefore all votes have equal weight. Under other election systems, a slight majority in a district – or even just a plurality – is all that is needed to elect a member or group of members. PR systems provide balanced representation to different factions, usually defined by parties, reflecting how votes were cast. Where only a choice of parties is allowed, the seats are allocated to parties in proportion to the vote tally or vote share each party receives.

Exact proportionality is never achieved under PR systems, except by chance. The use of electoral thresholds that are intended to limit the representation of small, often extreme parties reduces proportionality in list systems, and any insufficiency in the number of levelling seats reduces proportionality in mixed-member proportional or additional-member systems. Small districts with few seats in each that allow localised representation reduce proportionality in single-transferable vote (STV) or party-list PR systems. Other sources of disproportionality arise from electoral tactics, such as party splitting in some MMP systems, where the voters' true intent is difficult to determine.

Nonetheless, PR systems approximate proportionality much better than single-member plurality voting (SMP) and block voting.[30] PR systems also are more resistant to gerrymandering and other forms of manipulation.

Some PR systems do not necessitate the use of parties; others do. The most widely used families of PR electoral systems are party-list PR, used in 85 countries;[31] mixed-member PR (MMP), used in 7 countries; and the single transferable vote (STV), used in Ireland,[32] Malta, the Australian Senate, and Indian Rajya Sabha.[33][34] Proportional representation systems are used at all levels of government and are also used for elections to non-governmental bodies, such as corporate boards.Remove ads

Barriers to third party success

Summarize

Perspective

Winner-take-all vs. proportional representation

In winner-take-all (or plurality voting), the candidate with the largest number of votes wins, even if the margin of victory is extremely narrow or the proportion of votes received is not a majority. Unlike in proportional representation, runners-up do not gain representation in a first-past-the-post system. In the United States, systems of proportional representation are uncommon, especially above the local level and are entirely absent at the national level (even though states like Maine have introduced systems like ranked-choice voting, which ensures that the voice of third party voters is heard in case none of the candidates receives a majority of preferences).[35] In Presidential elections, the majority requirement of the Electoral College, and the Constitutional provision for the House of Representatives to decide the election if no candidate receives a majority, serves as a further disincentive to third party candidacies.

In the United States, if an interest group is at odds with its traditional party, it has the option of running sympathetic candidates in primaries. Candidates failing in the primary may form or join a third party. Because of the difficulties third parties face in gaining any representation, third parties tend to exist to promote a specific issue or personality. Often, the intent is to force national public attention on such an issue. Then, one or both of the major parties may rise to commit for or against the matter at hand, or at least weigh in. H. Ross Perot eventually founded a third party, the Reform Party, to support his 1996 campaign. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt made a spirited run for the presidency on the Progressive Party ticket, but he never made any efforts to help Progressive congressional candidates in 1914, and in the 1916 election, he supported the Republicans.

Micah Sifry argues that despite years of discontentment with the two major parties in the United States, third parties should try to arise organically at the local level in places where ranked-choice voting and other more democratic systems can build momentum, rather than starting with the presidency, a proposition incredibly unlikely to succeed.[36] However, this ignores that in some states a third party is required to have a presidential candidate in order to also run local level candidates.[citation needed]

Spoiler effect

Strategic voting often leads to a third-party that underperforms its poll numbers with voters wanting to make sure their vote helps determine the winner. In response, some third-party candidates express ambivalence about which major party they prefer and their possible role as spoiler[37] or deny the possibility.[38] The US presidential elections most consistently cited as having been spoiled by third-party candidates are 1844, 2000, and 2016.[39][40][41][42][43][44]This phenomenon becomes more controversial when a third-party candidate receives help from supporters of another candidate hoping they play a spoiler role.[44][45][46]

Ballot access laws

Nationally, ballot access laws require candidates to pay registration fees and provide signatures if a party has not garnered a certain percentage of votes in previous elections.[47] In recent presidential elections, Ross Perot appeared on all 50 state ballots as an independent in 1992 and the candidate of the Reform Party in 1996. Perot, a billionaire, was able to provide significant funds for his campaigns. Patrick Buchanan appeared on all 50 state ballots in the 2000 election, largely on the basis of Perot's performance as the Reform Party's candidate four years prior. The Libertarian Party has appeared on the ballot in at least 46 states in every election since 1980, except for 1984 when David Bergland gained access in only 36 states. In 1980, 1992, 1996, 2016, and 2020 the party made the ballot in all 50 states and D.C. The Green Party gained access to 44 state ballots in 2000 but only 27 in 2004. The Constitution Party appeared on 42 state ballots in 2004. Ralph Nader, running as an independent in 2004, appeared on 34 state ballots. In 2008, Nader appeared on 45 state ballots and the D.C. ballot.

Debate rules

Presidential debates between the nominees of the two major parties first occurred in 1960, then after three cycles without debates, resumed in 1976. Third party or independent candidates have been in debates in only two cycles. Ronald Reagan and John Anderson debated in 1980, but incumbent President Carter refused to appear with Anderson, and Anderson was excluded from the subsequent debate between Reagan and Carter. Independent Ross Perot was included in all three of the debates with Republican George H. W. Bush and Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992, largely at the behest of the Bush campaign.[citation needed] His participation helped Perot climb from 7% before the debates to 19% on Election Day.[48][49]

Perot did not participate in the 1996 debates.[50] In 2000, revised debate access rules made it even harder for third-party candidates to gain access by stipulating that, besides being on enough state ballots to win an Electoral College majority, debate participants must clear 15% in pre-debate opinion polls.[51] This rule has been in effect since 2000.[52][53][54][55][56] The 15% criterion, had it been in place, would have prevented Anderson and Perot from participating in the debates in which they appeared. Debates in other state and federal elections often exclude independent and third-party candidates, and the Supreme Court has upheld this practice in several cases. The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) is a private company.[51]

The Free & Equal Elections Foundation hosts various debates and forums with third-party candidates during presidential elections.

Major parties adopt third-party platforms

They can draw attention to issues that may be ignored by the majority parties. If such an issue finds acceptance with the voters, one or more of the major parties may adopt the issue into its own party platform. A third-party candidate will sometimes strike a chord with a section of voters in a particular election, bringing an issue to national prominence and amount a significant proportion of the popular vote. Major parties often respond to this by adopting this issue in a subsequent election. After 1968, under President Nixon the Republican Party adopted a "Southern Strategy" to win the support of conservative Democrats opposed to the Civil Rights Movement and resulting legislation and to combat local third parties. This can be seen as a response to the popularity of segregationist candidate George Wallace who gained 13.5% of the popular vote in the 1968 election for the American Independent Party. In 1996, both the Democrats and the Republicans agreed to deficit reduction on the back of Ross Perot's popularity in the 1992 election. This severely undermined Perot's campaign in the 1996 election.[citation needed]

However, changing positions can be costly for a major party. For example, in the US 2000 Presidential election Magee predicts that Gore shifted his positions to the left to account for Nader, which lost him some valuable centrist voters to Bush.[57] In cases with an extreme minor candidate, not changing positions can help to reframe the more competitive candidate as moderate, helping to attract the most valuable swing voters from their top competitor while losing some voters on the extreme to the less competitive minor candidate.[58]

Remove ads

Current U.S. third parties

Summarize

Perspective

Largest

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2025) |

Smaller parties (listed by ideology)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

This section includes only parties that have actually run candidates under their name in recent years.

Right-wing

This section includes any party that advocates positions associated with American conservatism, including both Old Right and New Right ideologies.

State-only right-wing parties

Centrist

This section includes any party that is independent, populist, or any other that either rejects left–right politics or does not have a party platform.

- Alliance Party

- American Solidarity Party

- Citizens Party

- Forward Party/Forward

- Liberal Party USA

- No Labels

- Reform Party of the United States of America

- United States Pirate Party

- United States Transhumanist Party

- Unity Party of America

State-only centrist parties

Left-wing

This section includes any party that has a left-liberal, progressive, social democratic, democratic socialist, or Marxist platform.

- Communist Party USA

- Freedom Socialist Party

- People's Party

- Party for Socialism and Liberation

- Peace and Freedom Party

- Socialist Action

- Social Democrats, USA

- Socialist Equality Party

- Socialist Alternative

- Socialist Party USA

- Socialist Workers Party

- Working Class Party

- Workers World Party

- Working Families Party

State-only left-wing parties

- Charter Party (Cincinnati, Ohio, only)

- Green Mountain Peace and Justice Party (Vermont)

- Green Party of Alaska

- Green Party of Rhode Island

- Kentucky Party

- Labor Party (South Carolina Workers Party)

- Liberal Party of New York

- Oregon Progressive Party

- Progressive Dane (Dane county, Wisconsin)

- United Independent Party (Massachusetts)

- Vermont Progressive Party

- Washington Progressive Party

Ethnic nationalism

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for granting special privileges or consideration to members of a certain race, ethnic group, religion etc.

- American Freedom Party

- Black Riders Liberation Party

- National Socialist Movement

- New Afrikan Black Panther Party

Also included in this category are various parties found in and confined to Native American reservations, almost all of which are solely devoted to the furthering of the tribes to which the reservations were assigned. An example of a particularly powerful tribal nationalist party is the Seneca Party that operates on the Seneca Nation of New York's reservations.[61]

Secessionist parties

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for Independence from the United States. (Specific party platforms may range from left wing to right wing).

Single-issue/protest-oriented

This section includes parties that primarily advocate single-issue politics (though they may have a more detailed platform) or may seek to attract protest votes rather than to mount serious political campaigns or advocacy.

- Grassroots–Legalize Cannabis Party

- Legal Marijuana Now Party

- Prohibition Party

- United States Marijuana Party[citation needed]

State-only parties

- Approval Voting Party (Colorado)

- Natural Law Party (Michigan)

- New York State Right to Life Party

- Rent Is Too Damn High Party (New York)

Remove ads

Electoral results

Summarize

Perspective

1944

1948

1952

1956

1960

1964

1968

1972

1976

1980

1984

1988

1992

1996

2000

2004

2008

2012

2016

2020

2024

In 2023 and 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. initially polled higher than any third-party presidential candidate since Ross Perot[62] in the 1992 and 1996 elections.[63][64][65] As Democrat Joe Biden withdrew from the race and the election grew closer, his poll numbers and notoriety would drop drastically.[66]

Remove ads

Maps

State wins

- 1892 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by James B. Weaver of the Populist Party.

- 1912 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by Theodore Roosevelt of the Progressive Party.

- 1924 United States presidential election; green denotes electoral votes won by Robert M. La Follette of the Progressive Party.

- 1948 United States presidential election; orange denotes electoral votes won by Strom Thurmond of the Dixiecrat.

- 1968 United States presidential election; Brown denotes electoral votes won by George Wallace of the American Independent Party.

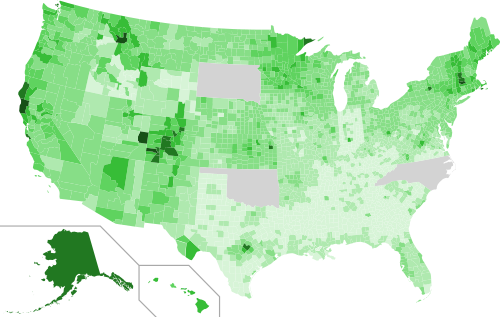

Vote percentages

- 2000 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Green candidate Ralph Nader

- 2016 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson

- 2016 United States presidential election results by county, shaded according to percentage of the vote for Green candidate Jill Stein

Remove ads

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads