Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

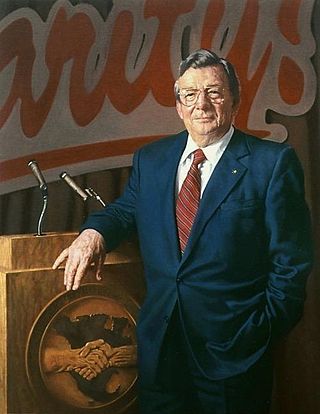

Tom Kahn

U.S. social democrat (1938 – 1992) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Tom David Kahn (September 15, 1938 – March 27, 1992) was an American social democrat known for his leadership in several organizations. He was an activist and influential strategist in the civil rights movement and a senior adviser and leader in the U.S. labor movement.[1]

Kahn was raised in New York City. At Brooklyn College, he joined the U.S. socialist movement, where he was influenced by Max Shachtman and Michael Harrington.[2] As an assistant to civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, Kahn helped organize the 1963 March on Washington.[1][2] Kahn's analysis of the civil rights movement influenced Rustin, who was the nominal author of "From Protest to Politics";[2][3] this article, originally a 1964 pamphlet from the League for Industrial Democracy, was written by Kahn, according to Rachelle Horowitz. It remains widely reprinted, for example in Rustin's Down the Line (1971) and Time on two crosses (2003).

A leader in the Socialist Party of America, Kahn supported its 1972 name change to Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA). Like other SDUSA leaders, Kahn worked to support free labor unions and democracy and against Soviet communism; he also worked to strengthen U.S. labor unions. Kahn worked as a senior assistant to and speechwriter for Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson, AFL–CIO Presidents George Meany and Lane Kirkland, and other leaders of the Democratic Party, labor unions, and civil-rights organizations.[1][2]

In 1980, Kirkland appointed Kahn to organize the AFL–CIO's support for the Polish labor union Solidarity[4][5] despite protests by the USSR and the Carter administration. Kahn began acting as director of the AFL–CIO's Department of International Affairs in 1986[6] and officially became director in 1989.[2] He died in 1992, aged 53.[1][2]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Kahn was born Thomas John Marcel[7] on September 15, 1938, and was immediately placed for adoption at the New York Foundling Hospital. He was adopted by Adele and David Kahn and renamed Thomas David Kahn. His father, a member of the Communist Party USA, became president of the Transport Workers Local 101 of the Brooklyn Union Gas Company.[2]

Tom Kahn was a civil libertarian who "ran for president of the Student Organization of Erasmus Hall High School in 1955 on a platform calling for the destruction of the student assembly, because it had no power", an election he lost.[2] In high school, he met Rachelle Horowitz,[2] who became his lifelong friend and political ally.[2][8]

Democratic socialism

As undergraduates at Brooklyn College (CUNY), Kahn and Horowitz joined the U.S. movement for democratic socialism after hearing Max Shachtman denounce the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary:[9] Shachtman described

rolling Russian tanks [...] defenceless Hungarian workers and students fighting back with stones [...] a heroic people's crushed hopes, and [...] our democratic socialist links to those hopes. Freedom, democracy—they were not abstractions; they were real and could therefore be destroyed. Communist totalitarianism was not merely a political force, an ideological aberration that could be smashed in debate; it was a monstrous physical force. Democracy was not merely the icing on the socialist cake. It was the cake—or there was no socialism worth fighting for. And if socialism was worth fighting for here, it was worth fighting for everywhere: socialism was nothing if it was not profoundly internationalist. I do not remember whether that was the night I signed up. But it was the night I became convinced.[10][11]

Kahn's and Horowitz's talents were recognized by Michael Harrington.[2] Harrington had joined Shachtman after working with Dorothy Day's Catholic Worker's house of hospitality in the Bowery of Lower Manhattan. Harrington was about to become famous for his book on poverty in the United States, The Other America. Kahn idolized Harrington, particularly for his erudition and rhetoric in writing and debate.[12]

Civil rights

As a leader of the American socialist movement, Harrington sent Kahn and Horowitz to help Bayard Rustin, a leader of the civil rights movement, who became a mentor to Kahn.[13][14] Harrington affectionately called Kahn and Horowitz the "Bayard Rustin Marching and Chowder Society".[15] Kahn helped Rustin organize the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington and the 1958 and 1959 Youth March for Integrated Schools.[16]

Homosexuality and Bayard Rustin

According to Horowitz, as a young man Kahn "was gay but wanted to be straight [...] It was a different world then".[17][18] He had a short relationship with a member of the Young People's Socialist League (YPSL):

Although everyone active in the movement was aware of it, [before 1956] he was never explicitly out of the closet. He took his sexual orientation as an affliction, a source of pain and embarrassment. In part, perhaps, because he was so unreconciled to his longings, he limited himself for a long time to brief encounters. But then he became involved with one of the YPSL's and was compelled to seek the counsel of a psychiatrist to explain his unfamiliar feelings. The diagnosis, he told me, was "you're in love."[19]

Kahn was "very good looking, a very attractive guy" according to longtime socialist David McReynolds,[17] also an openly gay New Yorker.[20] Kahn accepted his homosexuality in 1956, the year he and Horowitz volunteered to help Rustin with his work in the civil rights movement. "Once he met Bayard, then Kahn knew that he was gay and had this long-term relationship with Bayard, which went through many stages",[17] according to Horowitz, who quoted Kahn's remembrance of Rustin:

When I met him for the first time he was a few years younger than I am now, and I was barely on the edge of manhood. He drew me into a vortex of his endless campaigns and projects [...] He introduced me to Bach and Brahms, and to the importance of maintaining a balance in life between the pursuit of our individual pleasures and engagements in, and responsibility for, the social condition. He believed that no class, caste or genre of people were exempt from this obligation.[2]

Cohabiting in Rustin's apartment proved unsuccessful, and their romantic relationship ended when Kahn enrolled at Howard University, but Kahn and Rustin remained lifelong friends and political comrades.[21]

Howard University

Kahn enrolled for his junior and senior years at Howard,[22] where he became a leader in student politics. He worked closely with Stokely Carmichael, who later became a national leader of young civil-rights activists and then one a leader of the Black Power movement. Kahn and Carmichael helped fund a five-day run of The Threepenny Opera, by the Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht and the socialist composer Kurt Weill: "Kahn—very shrewdly—had captured the position of Treasurer of the Liberal Arts Student Council and the infinitely charismatic and popular Carmichael as floor whip was good at lining up the votes. Before they knew what hit them the Student Council had become a patron of the arts, having voted to buy out the remaining performances."[23] Kahn and Carmichael worked with Howard University's chapter of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Kahn introduced Carmichael and his fellow SNCC activists to Rustin, who became an influential SNCC adviser.[24] Kahn's and Rustin's emphasis on economic inequality influenced Carmichael.[25] Kahn graduated from Howard in 1961.[22][26]

Leadership

Kahn (along with Horowitz and Norman Hill) helped Rustin and A. Philip Randolph plan the 1963 March on Washington.[1][2][27][28] For this march, Kahn also ghost wrote Randolph's speech. Kahn's analysis of the civil rights movement influenced Rustin (the nominal author of Kahn's 1965 essay "From Protest to Politics"),[2][3] Carmichael, and William Julius Wilson.[2]

League for Industrial Democracy

In 1964, Kahn became director of the League for Industrial Democracy. Beginning in 1960, he had written several LID pamphlets, many of which were published in political journals like Dissent and Commentary and some of which appeared in anthologies.[29] His pamphlet The Economics of Equality gave an "incisive radical analysis of what it would take to end racial oppression".[30][31]

Student League for Industrial Democracy: Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)

Before Kahn became LID director, he was involved with the Student League for Industrial Democracy, which became Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Along with other LID members Rachelle Horowitz, Michael Harrington, and Don Slaiman, Kahn attended the LID-sponsored meeting that discussed the Port Huron Statement.[32] He was listed as a student representative from Howard University[33] and elected to the National Executive Committee.[34] The LID representatives criticized the Port Huron Statement for promoting students as leaders of social change, for criticizing the U.S. labor movement and its unions, and for its criticisms of liberal and socialist opposition to Soviet communism ("anti-communism").[35][36] According to Port Huron activist Todd Gitlin, Kahn believed the SDS students were "elitist" and overly critical of labor unions and liberals, attributing upper-class origins and Ivy League schooling to them.[34]

In 1965, LID and SDS split when SDS voted to remove from its constitution the "exclusion clause" that prohibited membership by communists, against Kahn's arguments.[37][38] The SDS exclusion clause had barred "advocates of or apologists for [...]totalitarianism".[39] The clause's removal effectively invited a "disciplined cadre" to attempt to "take over or paralyze" SDS, as had happened in mass organizations in the 1930s.[40] Afterward, Marxism–Leninism, particularly the Progressive Labor Party, helped write SDS's "death sentence".[40][41][42][43] But Kahn continued to argue with SDS leaders about tactics, strategy,[30] and accountable leadership.[44] In 1966, he attended SDS's Illinois Convention, where his arguments and delivery overwhelmed and were resented by other activists.[30]

Kahn's determined style of debate emerged from the socialist movement led by Max Shachtman. He expressed his admiration for Shachtman's intellectual toughness in his 1973 memorial:

His answers, of course, could not always be correct. But they were on target and always fundamental.[45]

Social Democrats, USA

Kahn and Horowitz were leaders in the Socialist Party USA, and supported changing its name to Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA),[2] despite Harrington's opposition.[46] Ben Wattenberg said that SDUSA members seemed to be

ingeniously trying to bury the Soviet Union in a blizzard of letterheads. It seemed that each of Tom's colleagues—Penn Kemble, Carl Gershman, Josh Muravchik and many more—ran a little organization, each with the same interlocking directorate listed on the stationery. Funny thing: The Letterhead Lieutenants did indeed churn up a blizzard, and the Soviet Union is no more.

I never did quite get all the organizational acronyms straight—YPSL, LID, SP, SDA, ISL—but the key words were "democratic", "labor", "young" and, until events redefined it away from their understanding, "socialist". Ultimately, the umbrella group became "Social Democrats, U.S.A", and Tom Kahn was a principal "theoretician."

They talked and wrote endlessly, mostly about communism and democracy, despising the former, adoring the latter. It is easy today to say "anti-communist" and "pro-democracy" in the same breath. But that is because American foreign policy eventually became just such a mixture, thanks in part to those "Yipsels" (Young People's Socialist League), with Tom Kahn as provocateur-at-large.

On the conservative side, foreign policy used to be anti-communist, but not very pro-democracy. And foreign policy liberal-style might be piously pro-democracy, but nervous about being anti-communist. Tom theorized that to be either, you had to be both.

It was tough for labor-liberal intellectuals to be "anti-communist" in the 1970s. It meant being taunted as "Cold Warriors" who saw "Commies under every bed" and being labeled as—the unkindest cut—"right-wingers".[47]

Kahn worked as a senior assistant and speechwriter for Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson, AFL–CIO Presidents George Meany and Lane Kirkland, and other leaders of the Democratic Party, labor unions, and civil rights organizations.[1][2] According to Wattenberg, he was an effective speechwriter because he could communicate ideas to an American audience.[47]

Estrangement from Harrington

Another protégé of Shachtman's, Michael Harrington, called for an immediate withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam in 1972. His proposal was rejected by the majority, who criticized the war's conduct and called for a negotiated peace treaty, the position associated with Shachtman and Kahn. Harrington resigned his honorary chairmanship of the Socialist Party and organized a caucus for like-minded socialists.According to Irving Howe, the conflict between Kahn and Harrington became "pretty bad".[48]

Harrington handed former SDS activist and New York City journalist Jack Newfield a speech by AFL–CIO President George Meany. Addressing the September 1972 Convention of the United Steelworkers of America, Meany ridiculed the Democratic Party Convention, which had been held in Miami:

We heard from the gay-lib [gay-liberation] people who want to legalize marriage between boys and boys, and between girls and girls ... We heard from the people who looked like Jacks, acted like Jills, and had the odor of Johns [customers of prostitutes] about them.

Harrington attributed this gay-baiting taunt to Kahn, and Newfield repeated it in his autobiography.[49] Maurice Isserman's biography of Harrington also describes this speech as reflecting Kahn's self-hatred.[50]

The blaming of Kahn for Meany's speech and Isserman's scholarship have been criticized by Rachelle Horowitz and by Joshua Muravchik, then an officer of the Young People's Socialist League (1907). According to Horowitz, Meany had many speechwriters—two specialists besides Kahn and even more writers from the AFL–CIO's Committee on Political Education (COPE) Department. Horowitz called it "inconceivable that Kahn wrote those words". She quoted a concurring assessment by Arch Puddington that Isserman "assumes that because Kahn was not publicly gay he had to be a gay basher. He never was."[51] According to Muravchik, "there is no reason to believe that Kahn wrote those lines, and Isserman presents none."[52]

Harrington failed to support an anti-discrimination (gay rights) plank in the 1978 platform of the Democratic Party Convention, but noted his personal support after being criticized in The Nation.[53] Along with others in the AFL–CIO and SDUSA, Kahn was accused of criticizing Harrington's application for his Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee to join the Socialist International and to organize a 1983 conference on European socialism; Harrington complained for six pages in his autobiography The Long Distance Runner, and "brooded" about Kahn's opposition, exaggerating the importance of the Socialist International to the U.S., according to Isserman's biography.[54] In 1991, even after Harrington's 1989 death, Howe warned Isserman that Kahn's description of Harrington "may well be a little nasty" and "hard line".[48]

AFL–CIO support for free trade unions

After becoming an assistant to the president of the AFL–CIO in 1972, a position he held until 1986, Kahn developed expertise in international affairs. In 1980 AFL–CIO officer Lane Kirkland appointed Kahn to organize the AFL–CIO's support for the Polish labor-union Solidarity, which was maintained and increased even after protests by the USSR and the Carter administration.

Support of Solidarity, the Polish union

Kahn was heavily involved in supporting the Polish labor movement.[4][5][56][57] The trade union Solidarity (Solidarność) began in 1980. The Soviet-backed Communist regime headed by General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared martial law in December 1981.

In 1980, AFL–CIO President Lane Kirkland appointed Kahn to organize the AFL–CIO's support of Solidarity. The AFL–CIO sought approval in advance from Solidarity's leadership to avoid jeopardizing its position with unwanted or surprising U.S. help.[4][55][56][58] Politically, the AFL–CIO supported the Gdansk workers' 21 demands by lobbying to stop further U.S. loans to Poland unless the demands were met. Materially, the AFL–CIO established the Polish Workers Aid Fund. By 1981 it had raised almost $300,000,[56] which was used to purchase printing presses and office supplies. The AFL–CIO donated typewriters, duplicating machines, a minibus, an offset press, and other supplies Solidarity requested.[4][55][56][58]

It is up to Solidarity ... to define the aid they need. Solidarity made its needs known, with courage, with clarity, and publicly. As you know, the AFL–CIO responded by establishing a fund for the purchase of equipment requested by Solidarity and we have raised about a quarter of a million dollars for that fund.

This effort has elicited from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Bulgaria the most massive and vicious propaganda assault ... in many, many years. The ominous tone of the most recent attacks leaves no doubt that if the Soviet Union invades, it shall cite the aid of the AFL–CIO as evidence of outside anti-Socialist intervention.[59]

All this is by way of introducing the AFL–CIO's position on economic aid to Poland. In formulating this position, our first concern was to consult our friends in Solidarity ... and their views are reflected in the statement unanimously adopted by the AFL–CIO Executive Council:

The AFL–CIO will support additional aid to Poland only if it is conditioned on the adherence of the Polish government to the 21 points of the Gdansk Agreement. Only then could we be assured that the Polish workers will be in a position to defend their gains and to struggle for a fair share of the benefits of Western aid.[60]

In testimony to the Joint Congressional Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Kahn suggested policies to support the Polish people, in particular by supporting Solidarity's demand that the Communist regime finally establish legality by respecting the 21 rights guaranteed by the Polish constitution.[61]

The AFL–CIO's support enraged the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and worried the Carter administration, whose Secretary of State Edmund Muskie told Kirkland that the AFL–CIO's continued support of Solidarity could trigger a Soviet invasion of Poland. After Kirkland refused to withdraw support for Solidarity, Muskie met with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobyrnin to clarify that the U.S. government did not support the AFL–CIO's position.[58][62][63] Aid to Solidarity was also initially opposed by neo-conservatives Norman Podhoretz and Jeane Kirkpatrick, who before 1982 argued that communism could not be overthrown and that Solidarity was doomed.[55][58]

The AFL–CIO's autonomous support of Solidarity was so successful that by 1984 both Democrats and Republicans agreed that it deserved public support. The AFL–CIO's example of open support was deemed appropriate for a democracy and much more so than the clandestine funding through the CIA that had occurred before 1970.[4] Both parties and President Reagan supported the non-governmental organization National Endowment for Democracy (NED) through which Congress would openly fund Solidarity through the State Department's budget beginning in 1984. The NED was designed with four core institutions, the two major parties and the AFL-CIO and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The NED's first president was Carl Gershman, a former SDUSA director and former U.S. Representative to the United Nations committee on human rights. From 1984 until 1990, the NED and the AFL–CIO channeled equipment and support worth $4 million to Solidarity.[5][64][65][66]

Director of the AFL–CIO's Department of International Affairs

In 1986, Kahn became director of the AFL–CIO Department of International Affairs, where he implemented Kirkland's program of a consensus foreign policy. Working with leaders from member unions, Kahn helped draft resolutions that represented consensus decisions on nearly all issues.[67]

Kahn acted as director of the AFL–CIO's Department of International Affairs in 1986,[6] after Irving Brown suffered a stroke and resigned; after Brown died in 1989, Kahn was officially named director.[68]

Living with AIDS

Earlier in 1986, Kahn learned that he was infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), then a terminal diagnosis. He wanted to spend his remaining years with his new partner,[69] who was "the love of his life",[8] but accepted the office of director out of a sense of duty, knowing that he was taking "a job that would most surely work him to death".[69] He warned his co-workers that his condition would bring cognitive decline and asked that they monitor him for signs of debilitation. The International Department's computer system was upgraded to allow Kahn to work from home.[8]

Kahn died of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Silver Spring, Maryland, on March 27, 1992, aged 53, after having been cared for by his partner and supported by his friends and colleagues.[8] He was survived by his partner, his sister,[1][2] and his niece.[6] Kahn planned most of his own memorial service, which was held at the AFL–CIO headquarters.[8]

Remove ads

Works

- "The Power of the March — And After," Dissent, vol. 10, no. 4 (Autumn 1963), pp. 316–320.

- "Problems of the Negro Movement," Dissent, vol. 11, no. 1 (Winter 1964), pp. 108–138.

- The Economics of Equality. Foreword by A. Philip Randolph and Michael Harrington. New York: League for Industrial Democracy, 1964.

- From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement. New York: League for Industrial Democracy, Feb. 1965. —Ghost written by Kahn, according to Horowitz (2007), pp. 223–224.

- "Problems of the Negro Movement," in Irving Howe (ed.), The Radical Papers. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1966; pp. 144–169.

- "Direct Action and Democratic Values," Dissent, vol. 13, no. 1, whole no. 50 (Jan.-Feb. 1966), pp. 22–30.

- "The Riots and the Radicals," Dissent, vol. 14, no. 5, whole no. 60 (Sept.-Oct. 1967), pp. 517–526.

- "The Problem of the New Left," Commentary, vol. 42 (July 1966), pp. 30–38.

- "Max Shachtman: His Ideas and His Movement," Archived 2010-06-20 at the Wayback Machine New America, Nov. 15, 1972.

- "Farewell to a Decade of Illusions," New America, vol. 11 (Dec. 1980), pp. 6–9.

- "How to Support Solidarnosc: A Debate." With Norman Podhoretz; introduction by Midge Decter; moderated by Carl Gershman. Democratiya, vol. 13 (Summer 2008), pp. 230–261.

- "Moral Duty," Transaction, vol. 19, no. 3 (March 1982), pg. 51.

- "Beyond the Double Standard: A Social Democratic View of the Authoritarianism versus Totalitarianism Debate," New America, July 1985. —Speech of January 1985.

Remove ads

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads