Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

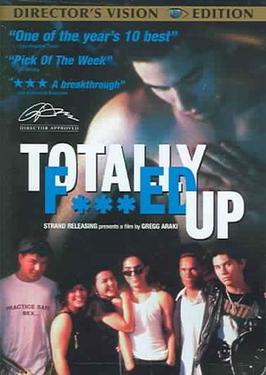

Totally F***ed Up

1993 film by Gregg Araki From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Totally F***ed Up (also known as Totally Fucked Up) is a 1993 American drama film written and directed by Gregg Araki. The first installment of Araki's Teenage Apocalypse film trilogy, it is considered a seminal entry in the New Queer Cinema genre.

The film chronicles the dysfunctional lives of six gay adolescents who have formed a family unit and struggle to get along with each other and with life in the face of various major obstacles. Araki classified it as "a rag-tag story of the fag-and-dyke teen underground....a kinda cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes flick." It premiered at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival.[2]

Remove ads

Plot

The plot is concerned with six teenagers, four of whom are gay men, the other two a lesbian couple. The plot is episodic, spliced with segments of other material and occasional tangents not central to the plot framed through the amateur documentary filmmaking of Steven, one of the teenagers, but it mainly follows a linear series of events. Araki has constructed the film in 15 parts, which is described in the opening titles.

The film details the lives and romances of the six characters, including Steven and Deric breaking up after Steven's infidelity, Deric being the victim of a gay bashing attack, and Michele and Patricia's attempts to conceive a child, before ultimately culminating at a climax in which Andy dies of suicide, and there is an epilogue-like reaction from the other five characters before the film ends.

Remove ads

Cast

- James Duval as Andy

- Roko Belic as Tommy

- Susan Behshid as Michele

- Jenee Gill as Patricia

- Gilbert Luna as Steven

- Lance May as Deric

- Alan Boyce as Ian

- Craig Gilmore as Brendan

- Nicole Dillenberg as Dominatrix

Production

Araki has said they shot on 16mm film without permits and that the film had "virtually no crew" and that he operated the camera himself, accompanied by only a sound person and producer/PA, and the cast.[2]

Style

The film makes extensive use of a handheld video camcorder, which one of the characters uses to provide insight into the lives of other characters through interview-like discussion. The technique - first seen in a major theatrical release with Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989) - became popular throughout the 1990s, evident also in such later films as Reality Bites (1994), American Beauty (1999) and The Blair Witch Project (1999).[3] Araki himself revisited the camcorder idea in his 1997 film Nowhere.

Remove ads

Home media

The film was released on Region 1 DVD on June 28, 2005. The film also has a region 2 release in the UK and Germany. These releases feature a commentary track with Araki, Luna and Duval. On September 24, 2024, The Criterion Collection released the film as part of its Gregg Araki's Teen Apocalypse Trilogy set. The film was restored in 2K resolution.[4]

Reception

In a negative review for Variety, Todd McCarthy called the film "a rather stale serving" and "murkier and harder to watch than Araki’s last picture". He criticized the film's "arbitrary structure and lack of interesting characters" as well as "the passive, victimized mind-set of [Araki's] characters".[5]

In The Austin Chronicle, Steve Davis wrote that the film centers on teens who are “disengaged from everything, both as a function of their age and sexual identity,” praising Araki’s unpolished style for amplifying this detachment.[6]

Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas noted that "Araki presents none of his young people, all of whom are played so expertly by his cast, as gay stereotypes but rather as indistinguishable in dress and mannerisms from other L.A. teen-agers," commending the film's rejection of caricature and its representational performances [7], adding to the reception of the film's authenticity.

In an interview with IndieWire, Araki said that young people are still being moved by his work "and there’s a whole new generation of kids accessing the Trilogy via DVDs, etc,"[2] solidifying its status.

Remove ads

Year-end lists

- 6th – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times[8]

See also

- Gregg Araki

- The Doom Generation (1995)

- Nowhere (1997)

- New queer cinema

- Independent film

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads