Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

1759–1767 novel by Laurence Sterne From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, also known as Tristram Shandy, is a humorous novel by Laurence Sterne. It was published from 1759 to 1767, in nine volumes across five instalments. The novel purports to be a memoir, but the titular Tristram is an effusive and digressive narrator who begins the story with his conception and doesn't reach a description of his birth until the third volume. While attempting to explain four accidents in his early life which have doomed him to an unhappy future, Tristram describes domestic conflicts between his irritable father Walter and his gentle Uncle Toby, and inserts humorous discourses on a range of intellectual topics.

Stylistically, Sterne is influenced by the earlier satirists Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Rabelais, and Cervantes. The novel is characterised by innuendo, especially sexual double entendre and aposiopesis (unfinished sentences). Sterne burlesques serious writers and genres, particularly parodying Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy and the genre of consolatio. The novel is also remembered for surprising visual elements, such as blank, black, and marbled pages; entire paragraphs censored with asterisks; and inserted diagrams.

Tristram Shandy was Sterne's first novel, and immediately transformed his life from that of an obscure rural clergyman to that of a literary celebrity. Eighteenth century audiences expressed some reservations about its daring and bawdy humour, especially given Sterne's religious profession, but praised its originality and its moments of sentimental morality. Over time, it has been an influential novel with a mixed reputation: Victorian audiences criticised it as obscene, but modernist and postmodernist authors embraced it in the twentieth century. Adaptations include the 2006 film A Cock and Bull Story, starring Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon as they metafictionally struggle to make the film.

Remove ads

Background

Sterne was an obscure and financially struggling Anglican clergyman in York when he wrote his first piece of fiction, a satire on church politics titled A Political Romance, in 1759.[1] This pamphlet was published in January of that year,[2] and was not received well within clerical circles: the Archbishop of York considered it embarrassing to make church conflicts so public,[3] and the pamphlet was burned.[4] Nonetheless, Sterne felt he had discovered his true talent for humour writing, and immediately began writing a new work.[5] He began and abandoned a "Rabelaisian Fragment" satirising sermon-writing, then began Tristram Shandy.[6]

Remove ads

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

The book is ostensibly Tristram's narration of his life story. But it is one of the central jokes of the novel that he cannot explain anything simply, that he must make explanatory diversions to add context and colour to his tale, to the extent that Tristram's own birth is not reached until volume three.

Consequently, apart from Tristram as narrator, the most familiar and important characters in the book are his father Walter, his mother, his Uncle Toby, Toby's servant Trim, and a supporting cast of minor characters: the chambermaid Susannah, Doctor Slop, Toby's love interest the Widow Wadman, and the parson Yorick, who later became Sterne's favourite nom de plume and the protagonist of Sterne's next novel.

Though Tristram is always present as narrator and commentator, the book contains little of his life, only the story of a trip through France and accounts of the four comical mishaps which he says have doomed him to an unfortunate life. Firstly, while he was still only an homunculus, Tristram's implantation within his mother's uterus was disturbed. At the moment of procreation, his mother asked his father if he had remembered to wind the clock. The distraction and annoyance led to the disruption of the proper balance of humours necessary to conceive a well-favoured child. Secondly, during his birth Tristram's nose was crushed by Dr. Slop's forceps, an ill omen according to his father's pet theory that a large and attractive nose is important to a man making his way in life. Third, a mistake caused him to be christened with an inauspicious name: another of his father's theories was that a person's name exerted enormous influence over that person's nature and fortunes, and he intended to use an especially auspicious name, Trismegistus (after the esoteric mystic Hermes Trismegistus). Susannah mangled the name in conveying it to the curate, and the child was christened Tristram. According to his father's theory, this conflation of "Trismegistus" and "Tristan" (conveying double sadness through its link to the tragedy of Tristan and Iseult and through folk etymology of Latin tristis, "sorrowful"), doomed him to a life of woe and cursed him with the inability to comprehend the causes of his misfortune. Fourth and finally, as a toddler, Tristram suffered an accidental circumcision when Susannah let a window sash fall as he urinated out of the window.

In between such events, Tristram as narrator finds himself discoursing at length on sexual practices, insults, the influence of one's name and noses, as well as explorations of obstetrics, siege warfare and philosophy, as he struggles to marshal his material and finish the story of his life. In addition to many real authors, he discusses the fictional writer Hafen Slawkenbergius. Most of the action is concerned with domestic upsets or misunderstandings, which find humour in the opposing temperaments of Walter—splenetic, rational, and somewhat sarcastic—and Uncle Toby, who is gentle, uncomplicated, and a lover of his fellow man.

Remove ads

Composition and publication

Summarize

Perspective

Tristram Shandy was published in nine volumes across five instalments over an eight-year period, from 1759 to 1767.[7] The first three instalments followed each other fairly rapidly: volumes one and two in December 1759, three and four in January 1761, and five and six in December 1761.[7] The fourth instalment, containing volumes seven and eight, was published in January 1765,[8] and the final instalment, volume nine, in January 1767.[9] Sterne characterised his writing process as highly spontaneous: "I begin with writing the first sentence——and trusting to Almighty God for the second".[10]

First two volumes

Sterne began writing Tristram Shandy some time early in 1759.[6] On 23 May of that year, he offered the manuscript of the first volume to the publisher Robert Dodsley, promising a second volume before the end of the year.[12] He asked £50 for the copyright to the text; Dodsley counter-offered £20;[13] Sterne instead printed the first two volumes at his own expense, with Dodsley as distributor.[14] This first print run, produced in York by Ann Ward,[15] was small – perhaps only 200 copies, and no more than 500 – and Sterne had to borrow money for the printing costs.[16] That he took on the financial risk himself is often seen as a sign of his confidence that the work would be a commercial success.[16] Volumes one and two were released in late December 1759, with the year 1760 printed on the title page.[17] The novel was an immediate success, which made Sterne's name for the rest of his life.[7] Dodsley purchased the copyright to both volumes in March 1760 for £250, and also promised £380 for the next two volumes;[18][a] he released his second edition, featuring an illustration by William Hogarth, in London on April 2, followed by several more editions as the novel continued to sell out.[20][7] Sterne visited London from March to May 1760 to promote the book and enjoy his newfound literary celebrity,[21] then returned to Yorkshire to write the next volumes.[22]

Later volumes

Two more instalments of the novel appeared in 1761.[23][24] Sterne finished volume three by August 1760, three months after his return to Yorkshire, and continued to make modifications until both it and volume four were printed.[25] He commissioned William Hogarth again to produce a frontispiece illustration.[26] Volumes three and four were published on 28 January 1761,[23] printed and sold by Dodsley in London and J. Hinxmann in York.[27] By November of that year, he had completed the next two volumes.[28] Dodsley and Sterne had ended their publishing relationship for reasons that are still unknown,[29][30] and Sterne did not sell anyone the copyright to volumes five and six.[31] In December Sterne arranged for Thomas Becket and Peter Dehondt to print and sell volumes five and six,[29] which appeared on 22 December 1761,[24] with 1762 on the title page.[32] By this time, fraudulent continuations by other authors had become so prevalent that Sterne autographed every copy of volume five to assure readers that it was legitimate; he repeated the practice in future instalments, signing all copies of volumes seven and nine.[7]

Sterne's intensive writing efforts worsened his tuberculosis, and in January 1762 he travelled to France to benefit from the warmer climate.[33] There, he wrote much less.[34] From August through November 1762, he worked on material about Uncle Toby which would eventually be used in volumes eight and nine.[35] In March 1764, Sterne returned to England, travelling via Paris and London and finally reaching Yorkshire in June.[36] He continued to delegate his clerical duties to the curate who had performed them during his absence,[37] and wrote.[38] Volumes seven and eight were finally completed in November 1764.[39] According to Sterne's biographer Arthur Cash, Sterne finished volume eight (primarily about Uncle Toby) before writing volume seven (primarily a travel narrative) but presented them in the reverse order within the novel.[39] He travelled to London to oversee the volumes' publication, and they appeared on 23 January 1765.[8] As with volumes five and six, Sterne served as his own publisher, with Becket and Dehondt as distributors.[40]

Sterne departed for another journey to France, and this time Italy as well, in October 1765,[41] and resumed writing Tristram Shandy on his return to Yorkshire in June 1766.[42] He decided to publish only one volume, to more easily begin a new serial novel, A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy.[42] In January 1767, he visited London, where he corrected the proofs for the forthcoming ninth volume.[43] Its release was advertised for January 8, but actually occurred January 29.[9] In March of 1768, Sterne died, very shortly after publishing the first instalment of the new serial A Sentimental Journey.[44] It remains uncertain whether Tristram Shandy should be considered a finished novel, or one that simply stopped with his death:[45] when he first planned A Sentimental Journey, he stated that he intended to continue Tristram Shandy alongside it,[42] but volume nine brings most of the storylines to satisfying stopping points so there are many scholars who consider it a fundamentally complete work.[7]

Remove ads

Analysis

Summarize

Perspective

Humour

A constant line of humour in the novel is innuendo, especially sexual double entendre.[46] In the words of the literary scholar Elizabeth Harries: "We quickly become aware that noses, whiskers, button-holes, hobby-horses, crevices in the wall, slits in petticoats, old cock'd hats, green petticoats, and even 'things' have more than one meaning– and that Sterne wants us to be aware of them all."[46] In many cases, the innuendo is implied through aposiopesis, a technique the novel draws attention to:[47]

"My sister, mayhap, quoth my uncle Toby, does not choose to let a man come so near her ****" Make this dash,——'tis an Aposiopesis.—Take the dash away, and write Backside,—'tis Bawdy.—Scratch Backside out, and put Cover'd-way in,—'tis a Metaphor;—and, I dare say, as fortification ran so much in my uncle Toby's head, that if he had been left to have added one word to the sentence,—that word was it.

— 2.6.116

As another form of humour, Tristram Shandy gives a ludicrous turn to solemn passages from respected authors that it incorporates, as well as to the consolatio literary genre.[48][49] Among the subjects of such ridicule were some of the opinions contained in The Anatomy of Melancholy by the seventeenth-century scholar Robert Burton. Burton's attitude was to try to prove indisputable facts by weighty quotations. His book consists mostly of a collection of the opinions of a multitude of writers; it discusses everything, from the doctrines of religion to military discipline, from inland navigation to the morality of dancing schools.[49] Much of the singularity of Tristram Shandy's characters is drawn from Burton, and Sterne parodies Burton's use of weighty quotations.[49] The first four chapters of Tristram Shandy are founded on some passages in Burton.[49] In volume 5, chapter 3, Sterne parodies the genre of consolatio, mixing and reworking passages from three "widely separated sections" of Burton's Anatomy, including a parody of Burton's "grave and sober account" of Cicero's grief for the death of his daughter Tullia.[48]

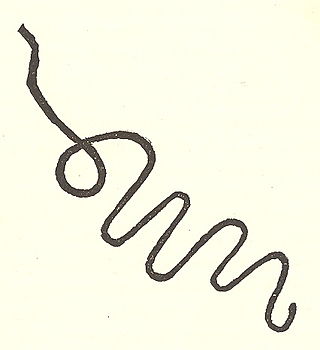

Unconventional visual elements

The novel is remembered for its surprising visual elements, which required innovative printing techniques.[50] One page is printed entirely in black in mourning for a character's death.[51] Another page is marbled, a complex and expensive addition which required the page to be individually added to each copy by hand.[50][25] At one point, a page is left blank; in other places, entire paragraphs are censored with asterisks.[50] The narrator claims to have taken out a chapter because it was so good, the rest of the novel would seem worse in comparison; the chapter numbering and pagination both skip ahead as if the pages had been physically removed.[50] Diagrams of wiggly lines are inserted as visualisations of the novel's wandering narrative structure.[50] Smaller and more frequent visual elements include near-constant dashes; manicules to direct the reader's attention; and pictographic devices, as in the following line: "What could Dr. Slop do? - - - He cross'd himself ✝ ⸺".[52] The literary historian Judith Hawley describes the reading experience as "paradoxical", because "Sterne draws attention to the physical medium of the book and the intellectual sophistications of the reading process, while also introducing us to a cast of charmingly individualized characters" who inspire a suspension of disbelief and an emotional attachment to the narratives that are continually interrupted.[53]

Allusions and influences

Tristram Shandy draws on a tradition of learned wit satire.[54][55] The text is filled with allusions and references to the leading thinkers and writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[48] The satirists Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Rabelais, and Cervantes were major influences on Sterne and Tristram Shandy.[48] Rabelais was by far Sterne's favourite author, and in his correspondence he made clear that he considered himself Rabelais's successor in humorous writing.[56][57] Sterne also frequently draws on Essays by the sixteenth-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, Richard Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy, Of Death by the early scientist Francis Bacon,[48] Swift's Battle of the Books, and the Scriblerian collaborative work The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus.[58]

The title page of the first volume features an epigraph in untranslated Greek. The unattributed quotation is from the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, and means "Men are disturbed not by things, but by their opinions about things."[59]

The novel also makes use of the philosopher John Locke's theories of empiricism, or the way we assemble what we know of ourselves and our world from the "association of ideas" that come to us from our five senses. Sterne is by turns respectful and satirical of Locke's theories, using the association of ideas to construct characters' "hobby-horses", or whimsical obsessions, that both order and disorder their lives in different ways. Sterne borrows from and argues against Locke's language theories (on the imprecision and arbitrariness of words and usage), and consequently spends much time discussing the very words he uses in his own narrative –with "digressions, gestures, piling up of apparent trivia in the effort to get at the truth".[60]

The Sterne scholar Melvyn New highlights that Sterne was not particularly influenced by the writers who eventually came to be known as the major novelists of the eighteenth century: Sterne never mentions Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, or Henry Fielding, and he only acknowledges Tobias Smollett through the unflattering parodic character Smelfungus. As such, despite writing prose fiction, Sterne stands apart from the development of the novel as a genre.[7]

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Eighteenth-century response

First instalment

The immediate success of Tristram Shandy made Sterne a literary celebrity for the rest of his life.[61] The literary historian Judith Hawley writes that the novel "dazzled readers with its originality and daring",[53] and it sold out several times in the first year.[62] Although Sterne was an active promoter of the book and attentive to its commercial potential, he publicly emphasised social rather than financial gains, saying "I wrote not [to] be fed, but to be famous".[10] He gained social patronage from William Pitt and Charles Watson-Wentworth (both future Prime Ministers),[62] was painted by the celebrity portraitist Joshua Reynolds,[63] and spent the spring in London enjoying social invitations from elevated society;[64] he wrote that "from morning to night my Lodgings ... are full of the greatest Company".[62] George Washington enjoyed the book.[65] Sterne answered to the names Tristram Shandy and Parson Yorick, using the personas of his fictional characters as part of his promotion for his book.[66]

There was some controversy when it was discovered that the novel — initially published anonymously — was written by a clergyman: its risqué humour was seen as incompatible with the moral solemnity expected of a religious figure, despite Sterne's invocations of the satirists-cum-priests François Rabelais and Jonathan Swift as precedents.[67] Sterne's biographer Ian Campbell Ross argues that this contradiction became part of Sterne's success: "What distinguished Sterne for many contemporaries was the surprising coupling of a laudable morality with whimsical bawdy. ...his literary and personal success lay precisely in joining contradictions."[68] Critics of the novel included the writers Samuel Johnson, who commented "Nothing odd will do long" and predicted that the novel would be forgotten,[68] and Horace Walpole, who wrote: "At present nothing is talked of, nothing admired, but what I cannot help calling a very insipid and tedious performance: it is a kind of novel called, The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy ... The best thing in it is a sermon — oddly coupled with a good deal of bawdy, and both the composition of a clergyman."[69] A more positive anonymous assessment praised Sterne's "infinite share of wit and goodness, things… which are very seldom, indeed, found in any degree together".[68]

Later instalments

Volumes three and four, published a year later, also sold well.[30] Sterne did not tone down the bawdiness of the novel, which was seen by some of his critics as an intentional provocation.[30] After this instalment, Sterne did not renew his publishing relationship with Dodsley, who has paid him generously for the copyright of the first four volumes; the reason is not known, but Sterne's biographer Ian Campbell Ross suggests that Sterne's insistence on controversial humour likely played a role.[30] Sterne was presented at court, though as a sign of his somewhat mixed reputation, King George III's reception was chilly.[30]

After publishing volumes five and six in late 1761, Sterne was pleased to discover that he was as large a celebrity in Paris as he had been in London, and spent six months enjoying his introductions to notable figures like the encyclopedist Denis Diderot.[63] He was painted by the prominent polymath Louis Carrogis Carmontelle.[63] This instalment sold more slowly than others, though a sentimental episode about a sick army officer (Le Fever) drew praise.[70] The fourth instalment, consisting of volumes seven and eight in 1765, was increasingly sentimental, and garnered praise for its pathos.[71] The fifth and final instalment, of volume nine in 1767, also met what Ian Campbell Ross calls "the usual mixture of extravagant praise and indignant censure",[72] though its slightly smaller print run (3,500 copies rather than the 4,000 of recent instalments) suggests that Sterne had experienced lagging sales.[73]

Nineteenth century

In the nineteenth century, the poet and critic Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) praised the novel.[74][b] The young philosopher Karl Marx was a devotee of Tristram Shandy, and wrote a still-unpublished short humorous novel, Scorpion and Felix, that was obviously influenced by Sterne's work.[75][76] The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe praised Sterne in Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years, which in turn influenced the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.[75][77] The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer called Tristram Shandy one of "the four immortal romances"[78] and the philosopher and logician Ludwig Wittgenstein considered it "one of my favourite books".[79] Among British writers, the novelists Walter Scott and Charles Dickens expressed appreciation for Tristram Shandy.[80]

However, many Victorian critics were hostile to Sterne on the grounds of obscenity.[48] Sterne's harshest critic in this period was the novelist and literary critic William Makepeace Thackeray, who denounced him in his lecture series on eighteenth-century English humorists.[81] Prompted by partly inaccurate biographical information, Thackeray censured Sterne for personal debauchery and profligacy, and argued that his writing was marred by "a latent corruption".[81] Other Victorian critics accused Sterne of plagiarism, often referencing an earlier work of analysis by writer and physician John Ferriar.[48] As Ferriar demonstrated in his 1798 book Illustrations of Sterne, Tristram Shandy incorporates many passages taken almost word for word from all of his influences, which have been rearranged to serve a new meaning.[48] Ferriar himself did not see these borrowings negatively and commented:[48][82]

If [the reader's] opinion of Sterne's learning and originality be lessened by the perusal, he must, at least, admire the dexterity and the good taste with which he has incorporated in his work so many passages, written with very different views by their respective authors.

Ferriar believed that, for example, Sterne's re-used passages from Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy were being creatively repurposed to ridicule Burton's solemn tone and weighty quotations.[49][83] Nonetheless, Victorian writers used Ferriar's findings to claim that Sterne was artistically dishonest, and almost unanimously accused him of mindless plagiarism.[48] Scholar Graham Petrie closely analysed the alleged passages in 1970; he argues that "Sterne's copying was far from purely mechanical, and that his rearrangements go far beyond what would be necessary for merely stylistic ends".[48]

Remove ads

Influence and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Tristram Shandy has been seen by formalists and other literary critics as a forerunner of many narrative devices and styles used by modernist and postmodernist authors such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Carlos Fuentes, Milan Kundera and Salman Rushdie. In particular, while the use of the narrative technique of stream of consciousness is usually associated with modernist novelists, Tristram Shandy has been suggested as a precursor.[84] The critic James Wood also identified the novel as a precursor to the "hysterical realism" of authors such as Rushdie and Thomas Pynchon.[85] Novelist Javier Marías cites Tristram Shandy as the book that changed his life when he translated it into Spanish at 25, claiming that from it he "learned almost everything about novel writing, and that a novel may contain anything and still be a novel."[86]

Tristram Shandy is often referenced in other literary works. Honoré de Balzac's novel La Peau de chagrin (1831) begins with an image from Tristram Shandy: a curvy line drawn in the air by a character seeking to express the freedom enjoyed "whilst a man is free".[88] In Anthony Trollope's novel Barchester Towers (1857), the narrator speculates that the scheming clergyman, Mr Slope, is descended from Dr. Slop in Tristram Shandy.[89] Surprised by Joy (1955) by C. S. Lewis self-consciously references Tristram Shandy when Lewis discusses his father.[90][c] In the Hermann Hesse novel Journey to the East (1932), Tristram Shandy is one of the co-founders of The League.[91]

Abolitionist influence

In 1766, the Black Briton Ignatius Sancho wrote to Sterne, encouraging him to lobby for the abolition of the slave trade.[92] Sterne replied that he had just been at work on "a tender tale of the sorrows of a friendless poor negro-girl", and volume nine included a scene with a Black shop girl too kindhearted to kill flies.[93] Sterne and Sancho's correspondence was widely publicised beginning in 1775, and this scene and their letters became an integral part of 18th-century abolitionist literature.[94][93]

Eponymous mathematical paradox

In philosophy and mathematics, the "paradox of Tristram Shandy" was introduced by Bertrand Russell in his book The Principles of Mathematics to evidentiate the inner contradictions that arise from the assumption that infinite sets can have the same cardinality—as would be the case with a gentleman who spends one year to write the story of one day of his life, if he were able to write for an infinite length of time. The paradox depends upon the fact that the number of days in all time is no greater than the number of years. Karl Popper, in contrast, came to the conclusion that Tristram Shandy—by writing his history of life—would never be able to finish this story, because his last act of writing (that he is writing the history of his life) could never be included in his actual writing.[95]

Remove ads

Adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

Michael Nyman has worked sporadically on Tristram Shandy as an opera since 1981.[96] At least five portions of the opera have been publicly performed[96] and one, "Nose-List Song", was recorded in 1985 on the album The Kiss and Other Movements.[97]

In 2005, BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation by Graham White in ten 15-minute episodes directed by Mary Peate, with Neil Dudgeon as Tristram, Julia Ford as Mother, David Troughton as Father, Adrian Scarborough as Toby, Paul Ritter as Trim, Tony Rohr as Dr Slop, Stephen Hogan as Obadiah, Helen Longworth as Susannah, Ndidi Del Fatti as Great-Grandmother, Stuart McLoughlin as Great-Grandfather/Pontificating Man and Hugh Dickson as Bishop Hall.[98]

The book was adapted on film in 2006 as A Cock and Bull Story, directed by Michael Winterbottom, written by Frank Cottrell Boyce (credited as Martin Hardy),[99] and starring Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon, Keeley Hawes, Kelly Macdonald, Naomie Harris, and Gillian Anderson. The movie plays with metatextual levels, showing both scenes from the novel itself and fictionalised behind-the-scenes footage of the adaptation process, employing some of the actors to play themselves. Like Tristram struggling to get his autobiography written, the filmmakers struggle to get the film made.[100]

Other adaptations include a graphic novel by cartoonist Martin Rowson in 1996,[101] a theatrical adaptation by Callum Hale presented at the Tabard Theatre in Chiswick in February 2014,[102][103] and a comic chamber opera by Martin Pearlman in 2018.[104]

Remove ads

See also

- The Path to Rome, a 1902 travelogue by Hilaire Belloc which has been compared stylistically

Notes

- He says: "The author of Tristram Shandy reveals to us the profoundest depths of the human soul; he opens, as it were, a crevice of the soul; permits us to take one glance into its abysses, into its paradise and into its filthiest recesses; then quickly lets the curtain fall over it. We have had a front view of that marvellous theatre, the soul; the arrangements of lights and the perspective have not failed in their effects, and while we imagined that we were gazing upon the infinite, our own hearts have been exalted with a sense of infinity and poetry."

- My father—but these words, at the head of a paragraph, will carry the reader's mind inevitably to Tristram Shandy. On second thoughts I am content that they should. It is only in a Shandean spirit that my matter can be approached. I have to describe something as odd and whimsical as ever entered the brain of Sterne; and if I could, I would gladly lead you to the same affection for my father as you have for Tristram's.[90] (The text of Tristram Shandy uses the phrase "my father" at the head of a paragraph fifty-one times.)

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads