Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Wampanoag-class frigate

US Navy steam frigates From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

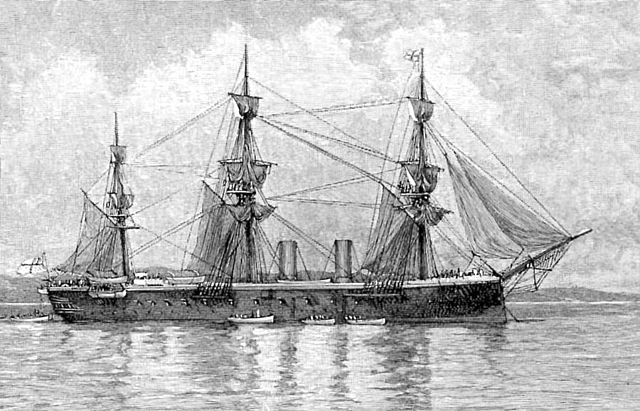

The Wampanoag class was a series of wooden-hulled screw frigates built for the Union Navy during the American Civil War. The ships were designed to decimate British merchant shipping in the event that the United Kingdom entered the war on the Confederate side. Of the eight ships planned, only five entered service and served brief careers. A combination of engineering, financial, and operational issues limited their practicality and service history even as the class's namesake, USS Wampanoag, was the world's fastest steamship.

Initially described as "commerce destroyers" and cruisers, the ships featured novel steam engines developed by different engineers, though three failed to reach the intended speed of 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h). Redundant at the end of the Civil War, their construction alarmed Britain during the Alabama Claims, prompting the Royal Navy to develop an equivalent vessel. Over time, the class's emphasis on speed over armor foreshadowed the evolution of the battlecruiser.

Remove ads

Development

Summarize

Perspective

Despite the United Kingdom's official stance of neutrality during the American Civil War, British assets were used to support the rebelling Confederacy, particularly in the development of its navy.[1][2] Shipyards in Liverpool constructed blockade runners and privateers for the Confederates, exploiting a legal loophole by ensuring the vessels were not armed until they reached Portugal. Among these ships were CSS Alabama, Florida, and Alexandra, which wreaked havoc on Union shipping; Alabama alone was responsible for destroying 65 merchant vessels.[2][3]

The Union Navy was alarmed by these developments, as the disruption of American trade routes drove up domestic prices, damaged the economy, and forced the reassignment of ships from blockade duties against the South. By 1863, the Union feared that Britain might intervene to support the Confederates directly - a scenario that would have left the Union Navy hopelessly outmatched by the Royal Navy. Faced with that prospect, the Union Navy began planning for a possible war with the United Kingdom. While the Union fleet could not match the Royal Navy in conventional battles, the plan called for employing commerce raiding. By using cruisers to launch hit-and-run attacks on British ports and merchant shipping, the Union hoped to make a war too costly for Britain to justify, ultimately forcing it back into neutrality.[4][5][6]

Remove ads

Design

Summarize

Perspective

Benjamin Isherwood, the Union Navy's Engineer-in-Chief, envisioned what he called a "commerce destroyer" for this new role. He proposed a large ship with the range to cross the Atlantic and loiter in British shipping lanes, a heavy armament capable of destroying any merchant vessels encountered, and a top speed of 15 knots (17 mph; 28 km/h) - fast enough to either overtake and attack shipping or evade the Royal Navy. To achieve this, his design incorporated both sails and steam engines. While steam engines of the era provided high speeds, they consumed an immense amount of fuel, making them only practical for combat. Outside of engagements, sails would ensure the necessary range for long voyages without concern for fuel.[7][4]

Engines

The primary issue with Isherwood's proposal was speed. At 15 knots under steam, the ships would be the fastest in the world. In comparison, most American warships operated at around 11 knots (13 mph; 20 km/h), while British merchant ships averaged 10 knots (12 mph; 19 km/h). To achieve this speed, the design featured long, narrow hulls - similar to those of fast clippers - paired with a high-power steam propulsion system created by Isherwood. His design included eight massive boilers, four of which were equipped with superheaters, that supplied steam to four engines with 100-inch (250 cm) wide pistons. The engines drove an 18-foot (5.5 m), four-bladed propeller through a novel gearing system designed to prevent excessive vibrations that threatened to rattle the ship apart.[4][5]

His design was immediately controversial, with objections to its slender hull form, reliance on engines as the primary source of propulsion, and his engine design. One critic was Edward Dickerson, a marine engineer who argued that the design would be highly inefficient based on the later-debunked theory that steam behaved as a perfect gas. After gaining support from elements within the Navy and Congress, Dickerson was granted the opportunity to design the engines for one of the ships, which was named Idaho.[8] John Ericsson, the naval architect behind USS Monitor, also opposed the concept. His ship, Madawaska, was built identically to Isherwood's Wampanoag, with the sole difference being its engines. Additionally, the firm Merrick & Sons was permitted to design the engines for another vessel, Chattanooga, while Isherwood's engines were installed in the rest.[6][4] By diversifying the engine designs, the Navy aimed to have each design compete against one another.[6]

Overview

With variations in each engine, the dimensions of each ship varied wildly, ranging from 3,043–4,446 short tons (2,761–4,033 t; 2,717–3,970 long tons) in displacement and between 298–335 feet (91–102 m) in length.[9] Due to the ship's fine hulls, no chaser (bow-mounted) or aft guns could be mounted, which would have limited the ships' ability to engage fleeing vessels. The exception was a single 60-pound (27 kg) rifled gun mounted on a pivot, although the Navy viewed it as inadequate and questioned its ability to fire forward. Instead, the rest of the armament was mounted on the broadside; the weapons on Wampanoag consisted of ten 8-inch (20 cm) smoothbore and two 100-pound (45 kg) guns along with two 12-pound (5.4 kg) howitzers.[a][6][5] The two ships built at private shipyards, Chattanooga and Idaho, were armed with 17 and 8 guns of unspecified types, respectively.[9]

While Isherwood wanted the ships to have iron hulls, shortages made him revert to wood. The ships were rigged as barks, had a straight stem as a stern, were fitted with four funnels, and lacked watertight bulkheads inside the hull.[6][9] In the ships fitted with Isherwood's engines, significant issues arose due to their sheer size. Weighing as much as 30% of the vessel's displacement, the engines occupied an enormous amount of internal space, leaving little room for coal storage, crew accommodations, and provisions.[6][10][9]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, the Navy faced severe funding cuts, which left many projects abandoned.[11] The frigates, which were nearly complete, suffered construction delays as funds dried up. The last ships in the class, Neshaminy, Pompanoosus, and Bon Homme Richard, were all ultimately canceled.[9][8]

Trials

The first ship launched, Idaho, fitted with Dickerson's engines, was an immediate failure. During her trials, she reached a top speed of just 8.27 knots (9.52 mph; 15.32 km/h) - barely half the intended 15 knots.[8] Madawaska, with John Ericsson's design, briefly hit 16 knots (18 mph; 30 km/h) but could only sustain 13 knots (15 mph; 24 km/h). The failure was attributed to Ericsson designing machinery better suited for an ironclad.[4] Similarly, Chattanooga managed 13.5 knots (15.5 mph; 25.0 km/h) but failed to meet the requirement while significantly wearing out her engines. All three ships built against Isherwood's design had failed.[6]

Following further scandals over engine costs and practicality, only Wampanoag and Ammonoosuc, the two ships fitted with Isherwood's engines, were completed and became serviceable.[6][9] On her maiden voyage, Wampanoag reached a top speed of 17.75 knots (20.43 mph; 32.87 km/h), averaging 16.6 knots (19.1 mph; 30.7 km/h), making her the fastest steamship in the world and a major vindication of Isherwood's work.[8][6] Likewise, Ammonoosuc exceeded the goal by breaking 17 knots (20 mph; 31 km/h).[12] Wampanoag held the world speed record for 11 years, and no American warship surpassed her speed until 1899.[6]

Later history

After her initial failure, Idaho was retained by the Navy and stripped of her engines. She was commissioned and sent to Japan, and was sold off after a typhoon ripped off her sails in 1869. Ammonoosuc and Chattanooga were laid up after their trials, and Madawaska was fitted with new engines and rebuilt.[9] Neshaminy was laid up at the New York Navy Yard between 1866 and 1869, only for her hull to be inspected and deemed economically unfixable. She was sold off in 1874 to John Roach as partial payment for the reconstruction of USS Puritan.[13]

In 1869, the Secretary of the Navy disapproved of the large number of warships named after Native American tribes and the incoherent naming conventions used across the fleet. As a result, he ordered a systematic renaming of vessels.[14] The five remaining Wampanoag-class frigates were subsequently renamed after American states.[9] That same year, the Navy assembled a board to review war-era vessels as part of budget reduction efforts. The board criticized the class, believing that their high speeds did not justify their costly operation, especially for a role that was no longer needed.[8][5] By 1870, just years after the class was launched, the entire class had been decommissioned and were gradually disposed of over the next two decades.[9]

Remove ads

Legacy

The original purpose of the frigates was rendered obsolete while they were still under construction. The British government, seeking to enforce neutrality during the Civil War, eventually seized vessels built for the Confederacy and closely monitored Confederate agents to prevent further support.[8][2] After the war, the United Kingdom perceived the Wampanoag-class frigates as a potential threat, which contributed to its willingness to pay for war damage. During the Alabama Claims, Britain agreed to pay $15.5 million in compensation for the damage caused by the British-built Confederate raiders, which helped to normalize Anglo-American relations.[15][8] The Royal Navy was interested in the Wampanoag's design, which lead it to build HMS Inconstant around a similar idea that favored speed over armor and armament: a concept that would later develop into the battlecruiser.[4]

Remove ads

Ships in class

Summarize

Perspective

Due to various differences in characteristics, sources vary on what constitutes being a part of the Wampanoag class. While all eight were built during the same program and to the same general design, some sources only include Wampanoag and Ammonoosuc, while others exclude Chattanooga and Idaho.[9][4][16]

Remove ads

See also

Footnotes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads