Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Wild man

Mythical figure From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The wild man (German: Wilder Mann, der Wilde Mann), wild man of the woods is a mythical figure and motif resembling a hairy human that appears in the art and literature of medieval Europe. Generally considered large-statured race of humans who are hairy all over its body, living in the wilderness or woodlands. They are often thought to be covered with moss, or wear green or vegetative clothing, and iconically wield a club or hold an uprooted tree as a staff. They also occur in female versions as wild women.

—Alte Pinakothek museum, Munich.

The Wilde Mann (Middle High German: wilde man) is attested in Middle High German literature, particularly German heroic epics[a] while the female Wilde Weib (wildez wîp) figures in the Arthurian works,[b] typically appear as adversaries. These beings are also called by names meaning "wood men"[c] and in older forms of the language, "wood wife"[d]. In Middle English a corresponding term for the wild man is woodwose or wodewose.

In the folklore of German-speaking areas collected mainly in the 19th century, there are especially the Alpine wild man and wild women. These beings could be man-hunters or otherwise be sinister, but could also endow luck or bounty, exhibiting aspects of woodland spirits.

The folklore that had developed in the mining areas around Harz or Ore Mountains by the 16th century regarded the wild man of the mines (also known as "mountain monk"[e]) as potentially both dangerous and beneficent, guiding humans to the discovery of ore deposits. The house of the Princes of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Brunswick-Lüneburg), which controlled one of the silver mines, minting silver thaler ("dollar") coinage with the wild man in their coat-of-arms, starting 1539.

These wild man had already frequently appeared in European family heraldic devices since the latter half of the 15th century.[f] It also became commonplace to depict the wild man as shield-bearers of the family coat of arms (e.g., within a portrait painting by Albrecht Dürer, cf. image right).[g] This period also roughly coincides with the popularization of the concept of the "noble wild man" or "noble savage" as can already be seen in Hans Sachs's "Lament of the Wild Men" (1530), and also reflected in artistic depictions of the wild folk from this period onward.

The defining characteristic of the figure is its "wildness"; iconography from the 12th century onward has consistently depicted the wild man as being covered with hair. Around the same transition period, biblical[h] or other humans afflicted with madness came to be conventionally depicted with hairiness, and subsequently, literary figures who temporarily loses sanity and live in the wild (Merlin, Ywain) also came to be associated with wild men.

Remove ads

Terminology

Summarize

Perspective

"Wild man" is a technical term in use since the Middle Ages, applied to a hairy human-like creature with certain animal-like traits but which has not quite descended to the level of ape; it may have hairless spots around the face, palms, feet, sometimes elbows and knees, and around the breasts in case of the female "wild woman". If the creature exhibits additional animal-like traits, it may not be a wild man in question, but rather the satyr, faun, or the devil (Bernheimer's definition).[2]

"Wild man" and its cognates in some languages are the common terms for the creature in most modern languages;[3] it appears in German as wilder Mann, in French as homme sauvage. But in Italian uomo selvatico "forest man" is often used.[4]

The German wild man (Der Wilde) also occurs in a more modern folklore tradition, localized in a region spanning from Switzerland to Carinthia, Austria (and often Hesse in Germany) according to the Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens (HdA),[5] registered under such names as wilde Frau,[6][7] Wildfrau, -en,[8][9] wilde Fraulein, Wildfräulein[10] wilder Mann,[11] Wildmannli,[12][13] wilde Männle.[14] Wildmännlein[15] Plural forms are: wilde Männer,[16] or wilde Leute[17][14] or wilde Menschen.[18] Females are also called wildes Weib (pl. wilde Weiber).[19] When the wild men appear in solitary fashion, they are similar to giants and ogres, while the women tend to be more goddess-like.[20]

The "wild man" is attested in Middle High German as wilde man in the 13th century, once in a lyrical poem[i] alluding to Sigenot[21] the older form of which only survived in fragments,[22] and elsewhere in the Arthurian romance Wigamur which gives wilde man (v. 203),[23] as well as the female form wildez wîp (vv. 112, 200, 227ff.)[24] (For additional examples in MHG literature cf. § German epics below).

In Old High German, the term wildaz wîp (lit. 'wild wife, wild woman') together with holzmuoja, holzmoia (lit. 'wood maiden') occurs in a glossary[j] as equivalent to Latin lamia (female monster); the same glossary also has an entry for the form wildiu wîp equated to Latin ulula (lit. 'screech owl', cf. strix of mythology.[k][l][26][27][25]

Another old example is the mention of "ad domum wildero wîbo" ("house of the wild women"), a piece of landmark or toponymy somewhere in Hessen,[29] mentioned in Codex Eberhardi (c. 1150) by the monk Eberhard of Fulda or a text close to it.[34][35][36][m]

Wood-folk type synonyms

The wild man is referred to as waltluoder in Wolfdietrich,[n][38] and in the same work, the title hero must deal with the advances of Rauhe Else ("Shaggy Else"), classified as a wild woman (cf. § German epic below).

In the epic Laurin the wild man is referred to as a waltmann (lit. 'wood man').[38] The same term waltman is used in Iwein to characterize the herdsman as a wild man, and he is also described as being as hairy as a walttôren (lit. 'wood fool'[39])[40] (Cf. Iwein discussed below under § Medieval iconography).

In MHG a synonym for wild woman is holz-wîp (lit. 'wood wife').[42][43]

In modern regional folklore, the creatures with sylvan (wood-related) names that correspond to the Alpine wild folk are the Holzleuten or Moosleuten (wood- or moss people) of Central Germany, Franconia, and Bavaria;[20] Holzfräulein aka Waldfräulein, Waldweiblein of the Bohemian Forest and the Upper Palatinate;[20] the Waldweiblein and Moosweiblein (lit. 'moss maiden') of the Harz mountains region;[20] the Lohjungfer[o] (pl. Lohjungfern) of Halle in Saxony;[44] and the Buschweiblein (lit. 'bush maiden') of Westphalia.[45]

Other aliases

Folklore in Tyrol and German-speaking Switzerland into the 20th century speaks of a wild woman called Fänge (Faengge, Fankke),[46] which is a post-medieval neologism deriving from the Latin fauna, the feminine form of faun.[3] The wild women of the Alpine region are "identical to or closely related to" the Fänggen or the Salige (Salige Frauen).[45]

The wild man is called a Bilmon (corruption of "wild man") Salvadegh, or Salvanel in Wälsch-Tirol (present-day Trento Province),[47] which may be spelt Salvan or Salvang[48] with usage extending to Lombardy.[3] The wild man is called l'om salvadegh by Ladin language-speakers in Folgrait (Folgaria) and Trambileno; this is readily recognizable as equivalent to French l'homme sauvage, where Old French salvage derives from Latin silvāticus "sylvan, pertaining to forest".[47] Hence these names are related to Silvanus, the Roman tutelary god of gardens and the countryside.[3] The (medieval Latin) term silvaticus was in fact used in the sense of "wild woman" by Burchard of Worms in the 10th century,[49] and it has been suggested he was referring to beings who would have been called Selvang in dialect according to modern-day folklore.[50]

The local name Frauberte or Frau Berta was supposedly current either in Ronchi near Ala, or the aforementioned Folgrait and Trambileno areas.[47][51][p] Likewise there are a sort of wild women known as Berchtra or Perchta (diminutive: Perchtel) in Carinthia.[q][52]

It is contended that the Norgg[54] or Orke or Orge;[55][r] Lorgg[54] or Lorge;[s][t] or Nörglein,[55][u] Nörkel, Örggele in folklore from parts of the Alps, particularly Tyrol, also may correspond to the wild man,[56][57] with the proviso that these (especially diminutives) are names for "wild dwarf people".[58][60] This appears to be connected to Italian orco (Neapolitan: huorco, pl. orci) in the sense of "subterraneans"[v] (≈dwarfs[61] or gnomes[62]),[55] or perhaps rather a "harmless wild folk" version of the orco such as appears in the literary fairy tales of the Pentamerone.[63] The Italian orco is cognate to French ogre,[64] as is modern literary orcs,[65] and is related to Orcus, a Roman and Italic god of death.[66][3][w]

When the wild man herds livestock, he is called Geißler (goatherd) or Kühler (cowherd).[68] Waldfänke is also synonymous to wilder Mann,[70] and the form Waldfenken-Geißler is used in commentary.[71]

The Rüttelweib, Rittelweibe (lit. 'shaking wife'; pl. Rüttelweiber[x]) of the Giant Mountains is also considered another regional fabulous being corresponding to the wild woman of the Alpine Region.[20]

English terms

In Old English/Anglo-Saxon there is recorded wude-wāsa meaning "satyr" or "faun",[72] a compound of wude "woodland, forest" and wasa of uncertain etymology,[73][74] though perhaps meaning "forest dweller";[75] or else it may perhaps be a compound formed from *wāsa "being", from the verb wesan, wosan "to be, to be alive".[76]

From it has derived Middle English woodwose, wodewose, woodehouse also used to the present day,[y] (with variant spelling such as wodewese, etc.,[73]) understood perhaps as variously singular or plural.[z][73][3] The form wodwos[aa] occurs in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c. 1390).[77][73][ab] This wild man (woodwose) has no relation to the Green Knight, but is just another enemy whom Sir Gawain happens to encounter in journey.[80]

The Middle English word is first attested for the 1340s in the context of decorative piece of art depicting a wild man, namely a piece of tapestry of the Great Wardrobe of Edward III,[81][ac] but as a surname it is found as early as 1251, of one Robert de Wudewuse.[74] The Middle English term wodewoos meaning "wild man" is found embedded in the Anglo-Norman caption to a painting in the Taymouth Hours (15th century)[82] (cf. § Manuscript illuminations)

Remove ads

Medieval literature

Summarize

Perspective

Verbal descriptions of the wild folk in medieval literature will be mainly discussed here. Visual depictions during the medieval period will be discussed under § Iconography.

German epic

That the German epic Sigenot (cf. image right) featured both the giant named Sigenot and the wild man[83] was certainly known in the 13th century, as the minnesinger Heinrich Frauenlob sings "Wa kam mit Parcivale /ris' Sigenot unt der wilde man? (Where came the giant Sigenot and the Wild Man, with Parzival?)",[21] but the actual so-called elder Sigenot (13th century) is lost except in a fragmentary state,[22] so the attestations come from the younger Sigenot (15th century) as "wilde man, wild man.[84]

The female character Rauhe Else ("Shaggy Else") in Wolfdietrich is also considered a wild woman example. She is a hairy woman crawling on all fours trying to get Wolfdietrich to marry her, but when he does not comply, casts a spell that turns him into a madman roaming the woods. God commands her to reverse the spell, and Wolfdietrich is now willing to marry her ("so long as the wild woman gets baptized"[85]). Fortunately, when she dips into a spring she sheds her furry skin and transforms into a beautiful maiden, now calling herself Sigeminne.[86][87][88][89][ad] She (Rauch Elss, christened Sygemin) is also mentioned as being the first wife of Wolfdietrich in the Anhang zum Heldenbuch.[92][91]

In the Arthurian Wigamur there is the wildez wîp (wild woman) who dwells in a hole in a rock.[24] In another Arthurian epic Wigalois, the dwarf named Karriôz is explicitly stated to have a wildez wîp as his mother.[38] In Wigalois there also appears a monstrous female of the woods named Rûel (cf. image right) as an adversary to the title hero, and though she is also described as a "wild woman" by modern commentators, she is not to be confused with Karriôz's mother.[93]

French epic

A "black and hairy" forest-dwelling outcast is mentioned in the tale of Renaud de Montauban, written in the late 12th century.[94]

Although the romance of Valentine and Orson can be discussed as an example of a wild man narrative,[95] this is rather recognizable as a fictional treatment of the feral child.[96]

Welsh and Irish literature

For the Myrddin Wyllt (mad Merlin) Suibhne Geilt (Mad Sweeney) driven to live in the wilderness and interpreted by some modern commentators as exhibiting the Wild Man of the Woods motif, cf. § Celtic mythology (under §Medieval parallels) below.

Remove ads

Medieval to Renaissance transition

Summarize

Perspective

As the name implies, the main characteristic of the wild man is his wildness. Civilized people regarded wild men as beings of the wilderness, the antithesis of civilization. Such had been the medieval view through the High Middle Ages.[97] That is to say, the wild man had been something that civilized people strove to reject..[98]

The regard for the wild man as such an abominable fearsome character began to blunt, and by the 14th century in the example of the Bal des Sauvages held by King Charles VI of France (cf. § In dance and festival) the wild man was being employed in costume, not so much as embodiment of evil and savagery, but as a toything of court nobles.[99]

The paradigm had reversed and the Wild Man became the Noble Savage by the time of Spenser's The Faerie Queene (1590, 1596)[ae] and Hans Sachs's Klag der wilden holtzleut uber die ungetrewen welt ("Lament of the Wild Men about the Unfaithful World", 1530) and it became a iconic model.[af][102][103] Bernheimer analyzes this as a backlash reaction by the nobility of having to live within the constraints of aristocratic conventions and chivalric code.[104]

Although emergence of the concept of the "Noble Savage" (French: bon sauvage) had occurred post-discovery of the Americas, according to one observer[105] not inconsistent with the foregoing 16th century examples, much of the scholarship on the Noble Savage pertains to thinking of the Enlightenment Period (18th century). The coinage of the term "noble savage" itself has often been (falsely) attributed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, [106] though refuted;[107] as Rousseau never actually used that term himself, even though the philosopher did profusely use the construct of "savage" to critique various aspects of civilized society.[108]

Modern recorded folklore

Summarize

Perspective

The purported nature of these wild folk or wood people in folklore, like the lore of demons in general, is highly ambiguous, unpredictable and mutable.[45]

Physical characteristics

Giants or dwarfs

The wild people can be dwarfish or be gigantic in size.[109] And this may not necessarily be regional variations: the wild folk of Bernhardswald (in Schlüchtern Hesse) are purported to be giants or dwarfs depending on the season.[ag][111]

They can be of different temperaments, but may exact vengeance on those who are frightened by them,[113] or mock them [115] In that case, the smaller wild folk are more easily appeased, while the giant types will tear their tormentors apart[116] or curse them with "seven times seven generations of curses and woe"29)

Friedrich Ranke argues that the legends concerning the wild people in Central Germany became less frightening, because the forests themselves shed much of their eeriness due to development and deforestation, so that only the low rolling hills remained. Thus in this regions, the folklore concerned the wild little folk of "harmless good nature",[ah][117]

Attire

The wild man stereotypically carries an uprooted fir tree,[119][120] or an iron club[121] or an iron pole,[122] etc.

Alpine wild man

There are also the Alpine wild man recorded by modern folklorists, whose lore is generally found in the lore of Alps (mountainous Italian Tyrol and Italian and German-speaking parts of Grisons, Switzerland). The wild man of the Alps had the reputation of abducting women and devouring humans, particularly children. In Grisons it is also accused of depositing its changeling child, swapping it with a human baby.[123] Allegedly peasants in the Grisons tried to capture the wild man by getting him drunk and tying him up in hopes that he would give them his wisdom in exchange for freedom.[124] This is noted as paralleling the capture of Silenus already described by Xenophon (d. 354 BC),[124] with Silenus being described as a satyr which Midas caught by getting him drunk with wine.[125][ai]

Legend also has it that humans were able to capture it once by getting it drunk, thereby learning the manufacture of cheese.[aj][47]

A legend from Folgrait (Folgaria) has it that a certain man heard the noise of the wild man hunting, and called out to him in rhymed couplet to give him a share,[ak] and received half a human corpse at his doorstep, subsequently having to take the trouble to have the hunter take back the unwanted gift.[126][47] There are also variant versions with different rhymes from Ritten and Barbian.[128][al] However, in a cognate tale from Vallarsa, the wild hunter is not specified as a "wild man".[129] It is comparable to a similar wild hunter myth from Northern Germany, that if anyone calls out to heckle the hunt, hunter forces a "half portion" (Halb Part) of foul-smelling game or human part, reciting a couplet that if you join in the hunt, you must help out with the chewing.[131]

A legend held that Wildmannli dwelled in the Gross Windgällen mountain in the canton of Uri, Switzerland that disapproved of humans hunting on Sundays, and a hunter who breached the taboo and shot a chamois was turned to stone.[132]

Alpine wild woman

—Woodcut by Maria Braun (1921)[133]

Meanwhile, the Tyrolian and Swiss Fängge (Faengge, Fankke)[46] as well as the Austrian Salige Frau are (subtypes or aliases of the) wild woman.[134]

The wild woman basically matches the female version of the wild man in appearance, and notably has drooping breasts[135][136][27] (for which the Tyrolean wild woman has earned the nickname Langtüttin[137][138] however, she may appear in the form of beautiful women.[139]

The wild woman, the Fängge, and the Salige Frau are all associated with protecting alpine game, especially the chamois[am][140][141] The legendary protectress called Kaiserfrau of Nachtberg (a peak situated between Thiersee and Brandenberg, Austria) is not explicitly called a wild woman in the original telling,[142] but is classified as such.[143] In the tale, the tall woman dressed in green robe commands a shepherd to kill all poachers, otherwise she will destroy his entire flock. He obliges, and due to the reputation the Kaiserfrau harms hunters, the stock of game in the forest rebounds.[142]

The wild women of Styria, Austria were said to reside mostly on Mt. Schöckl. They have a hollow or trough[an]-like back (hence comparable to the skogsnuva of Sweden[145]), so they can pretend to be old tree trunks instantly by turning their backs, even when a hiker senses the presence of the beautiful wild woman. The wild women of Schöckl are said to be hunted by the Wild Hunt that travels on flying sleds carrying demons.[146][ao]

Remove ads

Iconography

Summarize

Perspective

In art the hair more often covers the same areas that a chemise or dress would, except for the female's breasts (cf. fig. right); male knees are also often hairless. As with the feather tights of angels, this is probably influenced by the costumes of popular drama.

By the 12th century the wild folk were almost invariably came to be described as hairy all over,[148] having a coat of hair covering their entire bodies except for their hands, feet, faces above their long beards, and the breasts and chins of the females.[149]

Around the same 12th century, the conventions of hairiness came to be extended to certain legendary personages in mentally altered states.[150][aq] A prime example was the biblical Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon who went mad was no longer depicted as a smooth-bodied human, but a hairy creature. Other examples were ascetic saints[ar] (cf. § Biblical parallels) or literary hermits such as the Merlin of the Welsh (cf. § Celtic mythology) or Arthurian Ywain who were overcome by a spell of madness or lovelorn dementia (cf. § Celtic mythology).[153][154]

Bernheimer asserts that medieval paintings of Nebuchadnezzar came to be conventionally depicted as a wild man in crouching positions as according to contemporary ideas, though contradicting the biblical description in Daniel 4 (Book of Daniel, 2nd century BC) which ascribed him feather-like growths of hair like eagles, and bird-like claws.[155]

The wild man was used as a symbol of mining in late medieval and Renaissance Germany. The town of Wildemann in the Upper Harz was founded during 1529 by miners who, according to legend, met a wild man and wife when they ventured into the wilds of the Harz mountain range. For use as heraldic devices in the German mining area and elsewhere, cf. § Heraldry below.

Some early sets of playing cards have a suit of Wild Men, including a pack engraved by the Master of the Playing Cards (active in the Rhineland c. 1430–1450), some of the earliest European engravings. A set of four miniatures on the estates of society by Jean Bourdichon of about 1500 includes a wild family, along with "poor", "artisan" and "rich" ones.

Remove ads

Medieval iconography

Summarize

Perspective

Some of the earliest evidence for the wild-man tradition appears in the above-mentioned 9th- or 10th-century Spanish penitential.[67] This book describes a dance in which participants donned the guise of the figures Orcus, Maia, and Pela, and ascribes a minor penance for those who participate with what was apparently a resurgence of an older pagan custom.[67][as]

Manuscript illuminations

—Syracuse University Library ms. Latin, f.104v

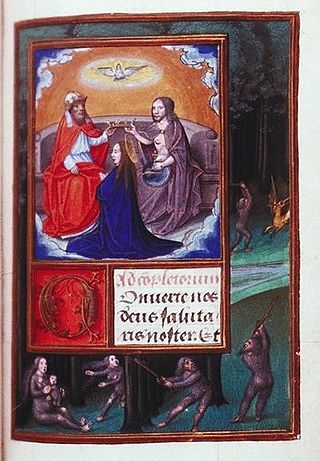

The wild folk are featured in the marginal paintings (drollery) in a number of illuminated manuscripts. There are wild men and women painted in the narrative border around the miniature of the Coronation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Book of Hours held at the Syracuse University Library (cf. fig. left).[156]

In the Taymouth Hours (15th century), there are a series of miniatures (bas-de-page illustrations) recounting a story of a wild man abducting a maiden. Though the captions in this work are written in Anglo-Norman French, the wild man is called wodewose, which is a Middle English term.[82][158]

There is also the drollery of a wild man being baited by three dogs, in the Queen Mary Psalter (14th century).[160][161][162]

Mural art

The herdsman character who is only a vilain in Chrétien 's Old French Yvain, the Knight of the Lion (though described as a "wild man" in modern scholarship[163]) is literally a wild man (waltman, "man of the woods") in Hartmann's Middle High German Iwein.[40] The wild herdsman is depicted as a club-carrying wild man on one of the fresco murals of the Iwein cycle at Rodenegg Castle (Castello di Rodengo) in South Tyrol (cf. image right).[164] The wild man is similarly painted on the mural at Schmalkalden Castle (Wilhelmsburg Castle). The man wears a skin with two paws attached to it, perhaps the influence of the Greek hero Hercules (wearing the lion skin).[165]

There is a giantess room series among the Runkelstein Castle (Castel Roncolo) fresco murals, and the label "Fraw Riel" suggests identification with the female Rûel of Wigalois (mentioned above as being categorized as wild woman by some modern commentators).[166][at] The Runkelstein frescos are themed on a triads of heroes, giantesses, and giants, etc. The giant Schrutan is one of them,[166] who figures in the epic Rosengarten zu Worms as one of the single combat participants.[au][169][167] Although clad in knightly armor, he holds an uprooted tree, and the Schrutan in this painting is "encoded as a giant-wild man hybrid" according to one art critic.[170]

Engravings

Albrecht Dürer depicts the wild man pursuing the maiden in his "Coat of Arms of Death" (1503), of which it is commented that the wild man springs to life from the conventional immobile role as shield-bearer of heraldic device (cf. also another of his work discussed under § Wild Men as shield-bearer below).[171][172]

English examples

Carved image of a group of wild men (woodwoses) engaged in battle with a beast form a roof boss in Canterbury Cathedral, and is grouped among a number of Green Man bosses present in the cathedral.[173][av] There is also a furry wild man depicted in the crypt of the Canterbury Cathedral.[aw][175][176] The visual artistic depictions of the English wild man (woodwose) and the green man merged during the Middle Ages to form a single type.[176]

Classical influences

There are instances where medieval depiction of satyr or faunus lose their beastly traits (hooves and horns), turning into creatures not so far apart from wild men.[177]

Medieval myth and art also adopted a convention of depicting the Greek hero Heracles, clad in lion skin and carrying a club as a wild man, sometimes of a more conventional type[ax] or more outlandishly as a tailed monster with clawed feet.[ay][179] (e.g. painting at Schmalkalden, described above)

Gallery of artwork

- Knight saving a woman from a wild man, ivory coffer, 14th century

- "Wild Man", c. 1521/22, bronze by Paulus Vischer

- Gargoyle, Moulins Cathedral

- Wild family, miniature by Jean Bourdichon, from a set showing The Four States of Society

Remove ads

Heraldry

Summarize

Perspective

Wild Men as shield-bearer

By the second half of the fifteen century, it became widely conventional to have engravings made of a wild man holding up a shield (escutcheon) bearing the family's coat of arms (cf. images left).[181][171] Particular examples include the Princes of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (cf. also § Numismatics below) and later by the royals of Brandenburg–Prussia.[182]

To avail themselves to this needs, the engravers came up with the idea of having a prototype or template at hand of a wild man holding up a blank shield, so that the proper emblem can be filled in to cater to the particular patron. Martin Schongauer was one such engraver,[183] four heraldic shield engravings of the 1480s which depict wild men holding heraldic shield (emblems of moor, greyhound, stag, and lion).[az]

Dürer in his Portrait of Oswald Krell (1499) drew two wild men supporting family heraldic shields. The one on the left wears a green garment made of moss, the one on the right is hairy all over (see image at top of page).[1]

The wild man appears in the coats of arms of e.g. Naila[184] and of Wildemann.[185]

- Arms of Kostelec nad Černými lesy, Central Bohemia

- Canting coat of arms of the city of Lappeenranta, Finland: the Swedish name of the city is Villmanstrand, originally spelled as Viltmanstrand

- The German Glücksburg dynasty used Heracles as a Hellenic version of a wild man when they became the royal family of Greece

- Coat of arms of the Dutch municipality of 's-Hertogenbosch (den Bosch), capital of the province of North Brabant

- Wild man, blazoned "demi-savage", on crest of Scottish clan Murray

Numismatics

The so-called Wildemannstaler was a type of taler (thaler, "dollar") denomination coins featuring a standing wild man on the reverse, first struck by Duke Henry the Younger of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel in 1539,[188][189] using the silver mined from the Upper Harz mountains.[190] Thus, much of this wild man is really part of silver-mining folklore, rather than alpine or forest region folklore.[191] The standing wild man on the early coin (and some heraldic illustrations) depicts a wild man holding a club (uprooted tree[192]) and a clump of burning flame in the other hand (cf. photo right).[188] The folkloric explanation of the flame is that it represents a light source or beacon of light to guide humans through the dark mine tunnels to the ore source or silver vein, as clarified by the work of Gerhard Heilfurth and Ina-Maria Greverus (1967).[193] Heilfurth regards the wild man in this context to be a type of Berggeist or "mountain spirit" (which is really a generic term or class used by modern folklorists), better known as Bergmönch or "mountain monk" in the folklore of the Harz mountains. The explanation of the "monk" name comes from the historical fact that the neighboring Walkenried Monastery held control of the workings of the Harz mining operation at one time.[194]

The lore of the mining spirit type wild man (or the BergmönchHeilfurth & Greverus (1967), p. 212) was localized mainly in the Harz and the Ore Mountains.[195] The folklore is attested in the following piece of 16th century writing, which stated that in the community of Wildemann (town named after "wild man"):

helt man dafür, daß daß Closter von Walckenred sonderlichen den Wildemanner Zog inne gehabt, beleget vnd gebawet hat, weil sich der Daemon Metallicus, der Bergteuffel, den die Bergleut daß Berg Mänlein nennen, in einer gestalt eines großen Mönchs hat sehen laßen, fürnemlich auff der Zechen Wildemann, da viel guter leute denselbigen gesehen, auch offtmals großen schaden gethan vnd angericht.

(It is believed that the Walkenried Monastery held, occupied, and built upon the Wildemann mine in particular, since the Daemon Metallicus or mountain devil, whom the miners call the "mountain manikin" (Bergmännlein, i.e. gnome), appeared in the form of a large monk, especially at the Wildemann mine, where many good people saw him, and he often caused great damage and destruction.

There is also the political and polemical interpretation of the wild man and flame emblem, namely, Henry the Younger was insinuating threat of violence, even the burning down of townships.[188][197] When Henry's less quarrelsome son Julius succeeded as duke, the flame on the coin was replaced by a candle or taper, and these coins are known as the Lichttaler or "Light taler" among numismatists. Later, Julius added other objects, the skull, the hourglass, and eyeglasses to the composition.[198][199]

Remove ads

In dance and festival

Summarize

Perspective

Wild man and wild woman of the Schembart Carnival of Nuremberg, From a 16th century manuscript.[200]

Aspects of German folk traditions about the wild man was preserved in performances of Wildemannspiel ("wild man play") and Wildemanntanz (dance), which tended to be held during Shrovetide/Carnival season.[201][202][203]

In the Morgestraich of the Carnival of Basel a wild man would take the first dance alongside other masked figures; this wild man held an uprooted tree in hand, and was entwined with leaves around the head and loins.[204] There is a 1435 account of the wild man dance in Basel featuring 23 such wild men (uomini selvatici).[205]

In the 15th century Fastnachtspiel (carnival play) "Ein spil von holzmennern", two men of the woods quibble over the female (holzweip) of their kind.[206][207] In Etschland (Etschtal),[ba] Ulten,[bb] and Vinschgau in South Tyrol,[209]. An example given of the Wildemannspiel conducted at Marling in South Tyrol: a youth and two younger boys are dressed up in beard moss hair, with a jangling chain of snail shells, holding a young tree as staff, and he waited in a cave towards St. Felix and dressed up schoolgirls were tasked to enter the forest and find the three of them.[210]

More examples come from civic celebrations or processions. At the Schembart Carnival of Nuremberg there were participants (German: Läufer lit. 'runners', or called "mummers") dressed up as a wild man (Holtzmendlein[211]) holding up a dwarf (on a stick) as captive, together with a wild woman (Holtzfrewlein), likely a man in "drag" (as the breast portion is laid bare) (cf. image right).[bc][212][213]

In Swiss locales of Vitznau, Weggis, Gersau, Küssnacht there is the Schämeler or Tschämeler representing the wild man,[214] with the local folk dressing up as them using moss, bark, leaves, etc., and holding a whole tree as staff.[215]

Outside of German-speaking regions, the (magnus) ludus de homine salvatico, a large-scale Pentecostal play about the wild man was put on in Padua in the year 1208, and 1224; not much is known about these except it featured giants (gigantibus). Another ludus was held in Aargau, Switzerland in 1399.[216]

It also became fashionable at one time for participants in the carousels at court festivals to dress up as club-carrying wild men (cf. image right).[217]

King Charles VI of France and five of his courtiers were dressed as wild men and chained together for a masquerade at the tragic Bal des Sauvages which occurred in Paris at the Hôtel Saint-Pol, 28 January 1393 (cf. image lef). They were suited up "six quilts of fabric coated with pitch then stuck with flax (linen) fibers in the form and shape of hair", making themselves out to be "hommes sauvages, covered in hair from head right up to the soles of their feet".[220][221] A careless torch set the costumers aflame, and all but one of the courtiers died; the king's own life saved by his aunt the Duchess of Berry, who covered him with her dress.[1][222][223] There exist paintings of this scene in copies of Froissart's Chroniques (as green men;[1] compare similar image right).[225] It is supposed that "dyed tufted flax" was used[221] to simulate the hair.

England's Henry VIII held a wild man dance on the Twelfthnight at the Great Hall of Greenwich in 1515[226]

The Burgundian court celebrated a pas d'armes known as the Pas de la Dame Sauvage ("Passage of arms of the Wild Lady") in Ghent in 1470. A knight held a series of jousts with an allegoric meaning in which the conquest of the wild lady symbolized the feats the knight must do to merit a lady.

Remove ads

Medieval parallels

Summarize

Perspective

Old High German had the terms schrat, scrato or scrazo, which appear in glosses of Latin works as translations for fauni, silvestres, or pilosi, identifying the creatures as hairy woodland beings.[3] Some of the local names suggest associations with characters from ancient mythology. Slavic has leshy "forest man".

Scandinavian folklore

The wild women of Styria, Austria were said to reside mostly on Mt. Schöckl. They have a hollow or trough[bd]-like back (hence comparable to the skogsnuva of Sweden[145]

Celtic mythology

There are medieval Welsh,[227][228] Irish,[229][228] and Scottish mythical narratives about men going mad and living in the wilderness, considered as part of the Celtic Wildman tradition according to scholars.[228]

The Welsh tradition regarding Myrddin Wyllt ("mad Merlin")[be] is that he went mad after the Battle of Arfderydd which took place in 573 AD in the wake of the battle that resulted in the death of Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio who was the king he served. It is recorded as suchin the annals, though it may not be historically accurate.[230] Myrddin then fled to the forest, living life as man of the woods, according to Giraldus Cambrensis (12th century).[231] The battleground (Arfderydd) became identified as a place near the Scottish border, making plausible the legend that Merlin's flight took him to the Caledonian Forest in Scotland.[230] Geoffrey of Monmouth recounts the Myrddin Wyllt legend in his Latin Vita Merlini of about 1150,[232] and the attachment of the madness motif may or may not have been Geoffrey's invention.[227]

The legend of the Scottish Lailoken who lost his wits in battle is so similar in background to the Myrddin legend, it is considered a version of the same myth,[228] and in fact, there is an aside comment that Lailoken might have been Merlin of Britain though that cannot be ascertained in the source itself,[227] namely the Lailoken fragment[228] or more precisely the Latin fragmentary The Life of Saint Kentigern.[227] There is also a geographical proximity of the battlegrounds involved,[233] pinpointable as present-day Arthuret in Cumbria, England.[230][227]

The Irish analogue[234][230] is the legend of Suibhne Geilt ("mad Sweeny"), a king [bf] of the Dál nAraidi who himself went mad during the combat of the Battle of Mag Rath of 637 AD[230][235] The legend is accounted for in Buile Shuibhne (The Frenzy of Sweeney, 9th century[236]).[230][238]

It is commented by James George O'Keeffe (1913) the Welsh and Irish versions exhibit the dispersed Wild Man (of the Woods) tradition.[229]

In Chrétien's Arthurian Romance Yvain, the episode when the title hero estranged from his lover Laudine lose his wits and lives in the wilderness, this has been characterized as a wild man episode by modern commentators.[163][239] Bernheimer lists Yvain, Lancelot, and Tristan among the Arthurian knights who chose to live as wild men in the aftermath of mental anguish having earned the disfavor of their beloved lady.[154]

The fragmentary 16th-century Breton text An Dialog Etre Arzur Roe D'an Bretounet Ha Guynglaff (Dialog Between Arthur and Guynglaff) tells of a meeting between King Arthur and Guynglaff ("a sort of wild man of the woods"), who predicts events which will occur as late as the 16th century.[240]

King's mirror

The notion of the Irish geilt, gelt (madness), which Grimm's notes glosses as equivalent to wilder mann or waldmann,[bg][241] is discussed in the Old Norse Konungs skuggsjá (Speculum Regale or "the King's Mirror", written in Norway about 1250),[243] which points to the Northmen having learned about the Suibhne legend from Ireland.[244]

There is also another item of Irish Mirabilia considered possibly relevant, namely, a sort of beast-man with a horse-like mane, which stooped when walking, and could not surely demonstrate the ability to comprehend speech.[246][247] Meyer thought this may have been a version of the "half-ox man" related by Giraldus[245] (cf. Gir. II.21[248]) William Sayers (1985) thought it may be connected to the Irish water horse (each uisge) despite lack of connection with water,[bh]

Slavic mythology

Wild (divi) people are the characters of the Slavic folk demonology, mythical forest creatures.[250] Names go back to two related Slavic roots *dik- and *div-, combining the meaning of "wild" and "amazing, strange".

Among the Bohemian populace, the wild man is known as lesní muž (pl. lesní mužove, lit. 'forest man'), who abducts a girl to forcibly make her his married wife.[251] The Bohemian wood woman has the reputation of forcing a girl to dance the night, but to undertake the yarn-spreading chore the girl missed, in fact endowing her an inexhaustible supply of yarn,[bi] but if the dancing partner is a boy, the wood woman tickles him to death.[28] The female Bohemian wild woman is called divý žena or divá žena (pl. divé ženy).[252]

In the East Slavic sources referred: Saratov dikar, dikiy, dikoy, dikenkiy muzhichok – leshy; a short man with a big beard and tail; Ukrainian lisovi lyudi – old men with overgrown hair who give silver to those who rub their nose; Kostroma dikiy chort; Vyatka dikonkiy unclean spirit, sending paralysis; Ukrainian lihiy div – marsh spirit, sending fever; Ukrainian Carpathian dika baba – an attractive woman in seven-league boots, sacrifices children and drinks their blood, seduces men.[250] There are similarities between the East Slavic reports about wild people and book legends about diviy peoples (unusual people from the medieval novel "Alexandria") and mythical representations of miraculous peoples. For example, Russians from Ural believe that divnye lyudi are short, beautiful, have a pleasant voice, live in caves in the mountains, can predict the future; among the Belarusians of Vawkavysk uyezd, the dzikie lyudzi – one-eyed cannibals living overseas, also drink lamb blood; among the Belarusians of Sokółka uyezd, the overseas dzikij narod have grown wool, they have a long tail and ears like an ox; they do not speak, but only squeal.[250]

Remove ads

Ancient parallels

Summarize

Perspective

Figures similar to the European wild man occur worldwide from very early times. The earliest recorded example of the type is the character Enkidu of the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh.[253][254]

Classical parallels

Classical wild races

"Classical antiquity like the Middle Ages, had its wild men", according to Bernheimer.[255] This included savage races of (sometimes hairy[255]) humans supposedly found in exotic places. Herodotus (c. 484 BC – c. 425 BC),'s wild men and wild women supposedly lived in western Ancient Lybia (a vast region west of the Nile, not just the present-day nation) where there also lived marvels such as men with eyes in their chest (headless men) and dog-faced humanoids (cynocephaly).[256] Ctesias[bj] (fl. 5th century BC)'s Indika and Alexander the Great (d. 323 BC)'s conquest influenced Europeans into thinking that such wild men (and the marvelous prodigies too[bk]) lived rather in the East, in the Indian subcontinent.[256]

Megasthenes[bl] (died c. 290 BCE), wrote of two kinds of men to be found in India whom he explicitly describes as wild: first, a creature brought to court whose toes faced backwards; second, a tribe of forest people who had no mouths and who sustained themselves with smells.[257] Both Quintus Curtius Rufus and Arrian (1st and 2nd centuries AD) refer to Alexander himself meeting with a tribe of fish-eating savages while on his Indian campaign.[258]

The wild man races described by the learned writings of ancient historians may have had influence on the Medieval wild man folklore but establishing the degree would be difficult given the separation in time. But one can catalogue which ancient pieces of writing were accessible to medieval men.[bm][255]

Distorted accounts of apes may have contributed to both the ancient and medieval conception of the wild man. In his Natural History Pliny the Elder describes a race of silvestres, wild creatures in India who had humanoid bodies but a coat of fur, fangs, and no capacity to speak – a description that fits gibbons indigenous to the area.[257] The ancient Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator (fl. 500 BC) reported an encounter with a tribe of savage men and hairy women in what may have been Sierra Leone; their interpreters called them "Gorillae," a story which much later originated the name of the gorilla species and could indeed have related to a great ape.[257][259] Similarly, the Greek historian Agatharchides describes what may have been chimpanzees as tribes of agile, promiscuous "seed-eaters" and "wood-eaters" living in Ethiopia.[260]

Silvanus

The medieval wild man lends itself to easy comparison with a number of classical woodland divinities. However, the aforementioned definition laid out by Bernheimer clearly distinguishes the faun and satyr from the wild man.[2] Grimm states that the German shaggy wood-sprite schrat answers to the classical faun, satyr, and perhaps even Silvanus.[261] Old High or Middle High German glossaries equating forms of the word schrat with faunus or sylvestri hominus.[241] Grimm speculate on the possibility schrat might have been a being of larger stature in olden times.[262]

The medieval wild man typically depicted holding an uprooted tree may have derived form the classical Silvanus who is lord of the gardens and uprooter of trees, though the latter is more prone to be holding a cypress sapling he is about to transplant.[177] The centaur is more likely to hold a club, though this creature is of course, half horse.[177]

Biblical parallels

The Christian Saint John Chrysostom (died 407)[152] purportedly had grown hair all over his body during his life in the wilderness, Late medieval legends.[94]

Earlier Christian writings on Desert Fathers as found in the Apophthegmata Patrum ("Sayings of the Desert Fathers") are similar, but less outlandish: typically their head of hair has grown long enough to cover their naked bodies.[105] A general term for to describe such ascetics living in the wilderness was Grazers (Ancient Greek: βοσκοί, romanized: boskoí) coined among the Greek or Eastern Christians.[bn] There is the hypothesis that notion of the "noble wild man" that emerged in the 15th century (after the European discovery of the Americas) may have been influenced by the notion of these "grazers".[105]

Remove ads

In modern fiction

Summarize

Perspective

Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale (1611), the dance of twelve "Satyrs" conflates wild men and satyrs.[265] The dance is held at the rustic sheep-shearing (IV.iv), described by a servant:

Masters, there is three carters, three shepherds, three neat-herds, three swine-herds, that have made themselves all men of hair, they call themselves Saltiers,[bo] and they have a dance which the wenches say is a gallimaufrey[bp] of gambols...[bq]

Petrus Gonsalvus (born 1537) was referred to by Ulisse Aldrovandi as "the man of the woods" due to his condition, hypertrichosis, and it is believed that his marriage to the lady Catherine inspired the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast.[non-primary source needed]

The term wood-woses or simply Woses is used by J. R. R. Tolkien to describe a fictional race of wild men, the Drúedain, in his books on Middle-earth. According to Tolkien's legendarium, other men, including the Rohirrim, mistook the Drúedain for goblins or other wood-creatures and referred to them as Púkel-men (Goblin-men). He allows the fictional possibility that his Drúedain were the "actual" origin of the wild men of later traditional folklore.[266][267]

British poet Ted Hughes used the form wodwo as the title of a poem and a 1967 volume of his collected works.[268]

The fictional character Tarzan from Edgar Rice Burroughs' 1912 novel Tarzan of the Apes has been described as a modern version of the wild man archetype.[253]

Remove ads

See also

Explanatory notes

- Middle High German: waltman.

- Old High German: holzmuoja,

- Cf. Christian I of Denmark's coat of arms (1449), with wild man as shield-supporter.

- Cf. also Martin Schongauer's works during the 1480s, described below.

- Prime example: Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon who went mad.

- By Heinrich Frauenlob, cf. § German epic below for further information

- Grimm explains ululae to be "funereal birds, death-boding wives, still called in later times klagefrauen.. resembling the prophetic Berhta" (for which cf. Frau Berta below), and altogether as denoting "she who wails or moos (German: muhende) in the forest". Lexer's definition of holzmuoje gives either a wood specter (Gespenst) or wood owl (Eule).[25]

- Bernheimer explains that lamia derives ultimately from Maia, a Greco-Roman earth and fertility goddess who is identified elsewhere with Fauna and who exerted a wide influence on medieval wild-man lore.[3]

- Rushing (2016), endnote 54 to Chapter 1, considers this mention of the wilde Weib to be one of the oldest references, relying Mannhardt's dating of 11th century.

- It is not clear if this Ronchi near Ala refers to Ronchital=Valle dei Ronchi that lies further east than Ala, Folgrait (Folgaria), or Trambileno.

- Called Pechtra or Pechtra-baba by the Carinthian Slovenes according to Graber, but only the -baba is a pan-Slavic stem.

- Definite or possibly diminutive forms: Orken, Orgen.

- Altered to Lorke by Bernheimer

- Definite or possibly diminutive form: Lorgen.

- Transliterated as Noerglein by Bernheimer.

- Importantly to Bernheimer, Orcus is associated with Maia in a dance celebrated late enough to be condemned in a 9th- or 10th-century Spanish penitential.[67]

- pl. var. Rüttelweibern, Rittelweibern.

- The term has been displaced in modern usage by "wild man", but it survives in the form of the surname Wodehouse or Woodhouse (see Wodehouse family).

- Perhaps understood as a plural in wodwos and other wylde bestes, and as singular in Wod wose that woned in the knarrez.

- The latinized term diasprez perhaps should be read as "diapered" meaning "embroidered" according to Warton, Thomas (1840) The history of English poetry; Wharton here also gives provides quoted Latin text, naming the source as Ex comp. J. Coke clerici, Provisor. Magn. Garderob. ab ann. xxi. Edw. III. de 23 membranis, ad ann. xxiii. memb. x.

- They walk high atop mountains and shake the treetops during stormy nights with flashes of lightning. They walk (as dwarfs) among the horsetails (de:Schachtelhalme) when the Arum (Aaronspflanze are in bloom.[110]

- Ranke (1924), p. 184, German: "harmlose Gutmütigkeit".

- And if they were able to detain him longer, would have learned how to make wax from milk. This motif of getting the wild man drunk to extract knowledge was seen above in the lore of the Grisons, with the Silenus parallel noted.

- „Wilder Mann, Glück und Hual, / Pring mir auch mein Thual!" where Hual should be read as Heil ("hail, health") and Thual as Teil ("part, portion").

- Zingerle's tale No. 124 is cited by Schneller for comparison.

- The term muldenartige — Mulde is vague, meaning shallow container or trough, but historically it refers to a Backtrog or bread trough.

- Cf. Salige Frau also said to be preyed on by the Wild Hunt.[147]

- There was some basis to this according to the shifting medieval scholarship. While Isidore of Seville (d. 636) had explained mental states in terms of the well-known Four humors (melancholia caused by black bile), Arnaldus de Villa Nova (d. 1311) would state that while mania was caused by the humour of choler, it could exhibit symptoms of animal-like physical transformations, and indeed, the medieval lay-person of that period believed that madman assumed shaggy forms.[151]

- Example of Saint John Chrysostom (died 407).[152] Late medieval legends developed claiming he was overgrown with hair all over his body when recaptured.[94]

- The identity of Pela is unknown, but the earth goddess Maia appears as the wild woman (Holz-maia in the later German glossaries), and names related to Orcus were associated with the wild man through the Middle Ages, indicating that this dance was an early version of the wild-man festivities celebrated through the Middle Ages and surviving in parts of Europe through modern times.[67]

- However, the fresco has this giantess holding Nagelring (Dietrich von Bern's sword) thus some confounding of names is involved.[166]

- The scene appears to be one of either a hunt or a baiting. Charles John Philip Cave reporting on animal themes in roof bosses reports that "bull-baiting is in the nave aisle at Winchester; in the Canterbury cloisters a bull is tossing a wild man".[174]

- Bernheimer guesses this might be a depiction of the Ichthyophagi from the Alexander Romance.

- Hercules as a wild man, illustrated in a manuscript containing poems by Robert de Blois (fl. second third of the 13th century.[178] ).

- 14th century illuminated manuscript of Seneca's Hercules Furens.

- Each image is confined within an approximately 78 mm circular composition which is not new to Schongauer's oeuvre. In Wild Man Holding a Shield with a Hare and a Shield with a Moor's Head, the wild man holds two parallel shields, which seem to project from the groin of the central figure. The wild man supports the weight of the shields on two cliffs. The hair on the apex of the wild man's head is adorned with twigs which project outward; as if to make a halo. The wild man does not look directly at the viewer; in fact, he looks down somberly toward the bottom right region of his circular frame. His somber look is reminiscent of that an animal trapped in a zoo as if to suggest that he is upset to have been tamed. There is a stark contrast between the first print and Shield with a Greyhound, held by a Wild Man as this figure stands much more confidently. Holding a bludgeon, he looks past the shield and off into the distance while wearing a crown of vines. In Schongauer's third print, Shield with Stag Held by Wild Man, the figure grasps his bludgeon like a walking stick and steps in the same direction as the stag. He too wears a crown of vines, which trail behind into the wind toward a jagged mountaintop. In his fourth print, Wild Woman Holding a Shield with a Lion's Head, Schongauer depicts a different kind of scene. This scene is more intimate. The image depicts a wild woman sitting on a stump with her suckling offspring at her breast. While the woman's body is covered in hair her face is left bare. She also wears a crown of vines. Then, compared to the other wild men, the wild woman is noticeably disproportionate. Finally, each print is visually strong enough to stand alone as individual scenes, but when lined up it seems as if they were stamped out of a continuous scene with a circular die.

- The term muldenartige — Mulde is vague, meaning shallow container or trough, but historically it refers to a Backtrog or bread trough.

- Cf. also name glossary on Myrdding Gwyllt in: Bromwich, Rachel (2014) [1961]. Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain (4 ed.). Cardiff: University Of Wales Press. pp. 458–459. ISBN 9781783161461. Cf. also notes to Triad #61, Tri Thar6 Ellyl (Three Bull-Spectres) of Britain.

- Not a historically recorded king, thus he was no more than lord.

- Grimm also says it compares to Myrddin Gwyllt.

- Sayers in turn offers comparisons with the Germanic analogues, i.e. nix, English nicker, Swedish bäckahästen and hints at reminiscence to the "Wild Man of the Woods motif".[249]

- A motif seen with the moss woman, as Mannhardt points out. Cf. also the legend of the Salk under Salige Frau.

- Seleucus I Nicator's ambassador to Chandragupta Maurya.

- Bernheimer actually speaks of "legends from the Mediterranean past" exerting "influence of these upon folklore, art, and imaginative literature". As to visual art § Classical influence was discussed above under §Iconography.

- Sault, "leap".

- Gallimaufrey, "jumble, medley".

- The account Shakespeare may have been inspired by the episode of Ben Jonson's masque Oberon, the Faery Prince (performed 1 January 1611), where the satyrs have "tawnie wrists" and "shaggy thighs"; they "run leaping and making antique action".[265]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads