Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Zichan

Chinese statesman of the State of Zheng (died 522 BC) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Zichan (WG: Tzu Ch'an) (traditional Chinese: 子產; simplified Chinese: 子产)[1] (c. 581–522 BCE)[2] was a Chinese statesman during the late Spring and Autumn period. From 543 BCE until his death in 522 BCE, he served as the chief minister of the State of Zheng. Also known as Gongsun Qiao (traditional Chinese: 公孫僑; simplified Chinese: 公孙侨,[3] he is better known by his courtesy name Zichan.

As chief minister of Zheng, an important and centrally located state, Zichan faced aggression from powerful neighbours without and fractious domestic politics within. He was a political leader at a time when Chinese culture and society was enduring a centuries-long period of turbulence. Governing traditions had become unstable and malleable, institutions were being battered by chronic war, and new forms of state leadership were emerging but were sharply contested.

Under Zichan the Zheng state prospered. He introduced reforms with strengthened the state and met foreign threats. His statecraft was respected by his peers and reportedly appreciated by the people. Favourably treated in the Zuo Zhuan (an ancient text of history), Zichan drew comments from his near-contemporary Confucius, later from Mencius and Han Fei.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

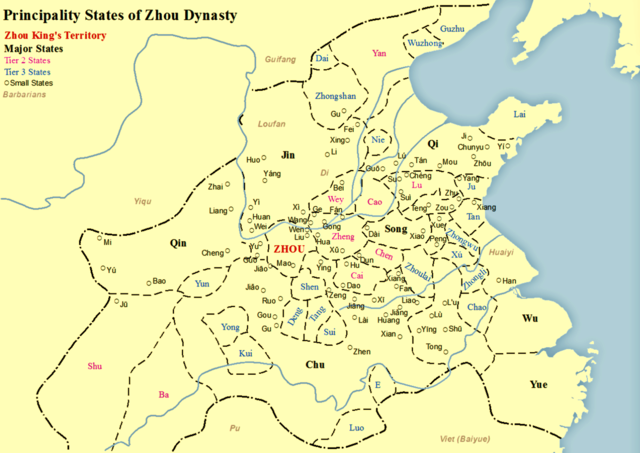

Zhou dynasty

By its military defeat in 771 BCE,[4] later historians divide the Zhou (c. 1045–221 BCE) into two periods: Western and Eastern, as Zhou moved its capital east over 500 km (310 mi).[5] The dynasty not only never recovered, its regime steadily lost strength during the Spring and Autumn period (770–481 BCE). At its start the Zhou rulers deployed the fengjian system. Differing from feudal estates,[6] in ancient China the patriarchal kinship relation formed the primary bond between the royal dynast and the local 'vassal'.[7][8][9][10][11] Regular state ceremonies sacrificing for Zhou clan ancestors, made by both royals and vassal rulers, at first strengthened the fengjian system.[12][13][14]

State of Zheng

Duke Huan (r. 806–771) founded Zheng, being enfeoffed by his brother the Zhou King Xuan (r. 825–782). As close kin, to remain near Zhou's new royal lands, by 767 BCE Zheng state had also moved its capital east.[15] Xinzheng was a walled city with a Grand Ancestral Temple, smaller clan temples, and a "great city gate" that led to the main thoroughfare (c. 600 BC);[16][17] population estimated at 10,000 (up to 100,000).[18][19][20][21] Strategically located,[22] Zheng prospered through trade,[23] at first fielding strong armies. Under Duke Zhuang (r. 743–701) Zheng in the Battle of Xuge (707) defeated the Zhou King's invasion.[24][25] Due to his wide influence Duke Zhuang was compared to the Five Hegemons.[26] In 673 BCE Zheng attacked the royal capital, killed the usurper, restoring the Zhou King.[27][28][29] Its military becoming less effective against its larger state rivals, a vigorous Zheng nonetheless manoeuvred to survive frequent attacks.[30]

During Zichan's youth, the reign of the figurehead Duke Jian of Zheng (r. 566–530) began. Political stability was precarious during the Eastern Zhou. The prior Duke of Zheng, Xi, had been killed by nobles in his ministry.[31][32][33][34] Zichan as leader confronted such political turbulence, yet achieved major civic reforms benefitting the state and its people. Later, during the Warring States (480–221) Zheng state relapsed, when "the centre of the political stage was occupied by the competition between clans".[35][36] That era's fierce warfare continued among the fewer states. Zheng state met its demise in 375 BCE.[37][38][39]

Family of Zichan

Zichan was closely related to the hereditary sovereigns, the Dukes of Zheng state,[40][41] hence also more distant kin of the royal Zhou.[42] As a grandson of Zheng's formidable Duke Mu (r. 627–606),[43] Zichan was also called Gongsun Qiao, "Ducal Grandson" Qiao. Zichan was a member of the clan of Guo, one of the Seven Houses of Zheng.[44] Led by their nobility these various clans competed (at times, by internecine strife) for power and prestige. The Guo lineage was not among the strongest clans of Zheng. Zichan's ancestral surname was Ji, his personal name Ji Qiao.[45][46][47]

In 565 BCE Zichan's father, Prince Guo (Ziguo),[48] led a victorious campaign against the State of Cai. His military success, however, risked provoking the hostility of stronger neighbouring states, Jin to the north and Chu to the south. Yet the Zheng leadership appeared pleased. However Zichan, the teenage son of Ziguo, had a different view. He said a small state like Zheng should excel in civic virtue, not martial achievement, else it will have no peace.[49] In response, Ziguo rebuked Zichan.[50][51][52][53][54] Three years after the Cai victory, during a revolt by rival nobles of Zheng, Zichan's father Ziguo was assassinated.[55][56][57]

Remove ads

Career profile

Summarize

Perspective

Path as state official

In 543 BCE, when nearing 40 years of age,[58][59] Zichan became prime minister of Zheng state. Zichan's career path to the top position started in 565 BCE,[60] and involved finding his way through the intense social instability, sometimes violent, and foreign threats, that challenged Zheng's aristocratic political class.[61] Selected events of his early career follow, the chief primary source being the Zuo Zhuan.[62]

Since 570 BCE Zichan's father Ziguo had been one of three leading aristocrats who directed Zheng's government. The head of state was the Duke of Zheng, but in fact this triumvirate of nobles kept control. In 563 BCE "Zisi had laid out ditches between fields" so that four clans "lost lands".[63] Later in 563 BCE "armed insurgents" led by seven disaffected clan nobles (many who had lost lands), overthrew the government and killed all three rulers: Zisi, Ziguo, and Zi'er.[64] Zichan recovered his father's body, and rallied his lineage. He "got all his officers in readiness... formed his men in ranks, [and] went forth with 17 chariots of war". Another "led the people" to Zichan's side. Two rebel leaders (and many followers) were killed; five leaders fled Zheng.[65][66][67][68] The ruling 'oligarchy' of elite and pugnacious Zhou-era nobles prevailed against the brutal assault by rebel clan leaders.[69][70]

After the 563 BCE rebellion was quelled, Zikong the new Zheng leader issued a document declaring his autocratic rule. It provoked fierce opposition from other nobility and the people. Zichan urged Zikong to renounce the document by burning it in public. His rhetoric to Zikong used likely scenarios to illustrate a probable negative outcome. Zikong then burned it.[71][72][73] In 553 BCE Zikong tried again to monopolize political power, supported by Chu state. But two nobles rose to fatally block him. The two formed a new triumvirate to rule Zheng, the third being the popular Zichan, elevated now as a high minister.[74][75][76]

In 561 BCE Zheng joined (or was recruited by) a coalition headed by the powerful Jin state to the north.[77] Zichan as a high minister maneuvered to ally Zheng with fellow small-state members, in order to lighten their burdens. Jin, as the current hegemon, required all 'northern league' members to make regular state visits to Jin, and each time to bring high-value gifts.[78][79] In 548 BCE Zichan wrote a convincing letter to Jin's chief minister. It criticised Jin for increasing the value of 'gifts' demanded. Zichan successfully argued this worked against Jin's reputation. Worth more than the gifts was Jin's good name; on it rested Jin's virtue, the very foundation of Jin state.[80][81][82] Zichan continued to lobby Jin on behalf of the small states.[83]

In 547 BCE Zheng started a popular war against the small state of Chen as pay back (a year earlier the large and powerful Chu state and Chen had attacked Zheng, "wells were filled up and trees were cut down").[84][85][86] With 700 chariots Zheng (with Zichan second in command) took the Chen capital. In the brief military occupation a ceremony was held with the Chen ruler, and the two Zheng leaders persuaded the city's priest "to sprinkle the altar of the earth". They then restored to Chen ministers their lists, seals, and charts. Zheng forces withdrew, without looting the city or destroying its sanctuaries, nor did the Zheng army seize hostages. For a military victor to act harshly, sack the enemy capital, and take vengeance was then customary in ancient China's multi-state system.[87][88][89][90][91][92] Zichan later defended Zheng's invasion of Chen before resentful ministers of Jin.[93][94][95]

In 544 BCE a feud had begun between two nobles of rival clans.[96][97] In 543 BCE it threatened the precarious unity of Zheng state.[98][99][100][101] Zichan kept his distance from the bitter conflict's social contagion; he was unable to stop it until after a battle. Yet by his following ritual propriety he led in restoring Zheng unity.[102][103][104][105] Zichan remained a popular leader.[106][107]

Han Hu, aristocratic clan leader and influential minister,[108] in 544 BCE wanted Zichan to become prime minister of Zheng. A reluctant Zichan had declined: the office was troubled from without by strong and aggressive rival states, and from within by the constant feuding of the clans, which made Zheng "impossible to govern well". Zheng state, however, avoided the worst of the era's fierce and lawless inter-clan violence.[109][110][111] By late 543 BCE Zichan had been persuaded enough by Han Hu that a tolerable coexistence between the nobility was more likely, sufficient for Zichan to pursue reforms.[112][113][114][115]

The merits of his political path in office, ably pursued apparently for decades, and his popularity, can be portrayed with skepticism. Prof. Lewis suggests a strikingly different interpretation (than the Zuo Zhuan) about the transfer of power to Zichan. First he gives a sequence-of-events summary to 543 BCE of his rise from the lower nobility to Zheng's highest office, while winning over the people. He then concludes, "Following another civil war in 543 BCE, Zi Chan seized effective power".[116][117] On the other hand, Zichan's career can viewed as anticipating the benevolent qualities of the Confucian ruler.[118]

Reform programs

Zichan initiated actions to strengthen the Zheng state. Along with subordinate ministers and aides,[119] Zichan scrutinized and straightened what reforms might work best over time, and improvised.

Agricultural methods were managed to increase the harvest. Boundaries between farmlands were reset. Tax reforms increased state revenue. The military was kept current. Laws were published, sharply breaking with tradition. Administration of state operations were centralised, effective officials recruited, social norms guided. Commerce flourished. Zhou-era rites were performed, in an evolving social context, and the religious needs of the people addressed. The culture and customs of Zheng state were followed, its special ministry for divinations was both curbed and instructed. Interstate relations required constant vigilance, e.g., to meet demands for tribute. His negotiating skills were tested. Zichan had opposition and acquired a sophist enemy. He did not always succeed.[120]

From the Han dynasty historian Sima Qian,[121] his Shiji:

Tzu-ch'an[122] was one of the high ministers of the state of [Zheng]. ... [Its affairs had been] in confusion, superiors and inferiors were at odds with each other, and fathers and sons quarrelled. ... [Then] Tzu-ch'an [was] appointed prime minister. After... one year, the children in the state had ceased their naughty behaviour, grey-haired elders were no longer seen carrying heavy burdens... . After two years, no one overcharged in the markets. After three years, people stopped locking their gates at night... . After four years, people did not bother to take home their farm tools when the day's work was finished, and after five years, no more conscription orders were sent out to the knights. ... Tzu-ch'an ruled for twenty-six years [sic], and when he died the young men wept and the old men cried... .[123][124][125]

The earlier Zuo Zhuan had also told of the people's appraisal of Zichan, a version similar to the Shiji, but differing in stages and detail. After one year the workers complained, griping about new taxes on their clothes and about a new levy against the land. Yet after three years the workers praised Zichan: for teaching their children, and increasing the yield of their fields.[126][127]

Yet however skilful his statecraft, Zichan in his reformist role as proponent of advanced policies was not unique. Over a century earlier Guan Zhong (720–645 BCE), the chief minister of Qi, earned praise for his effective management. His innovations included administrative and military-agricultural innovations. The Qi state nonetheless maintained traditional Zhou rituals. As a consequence Duke Huan of Qi became the 'first' of the Five Hegemons, and a noted "paragon".[128][129][130][131] Another reformist minister was Li Kui (455–395 BCE) of Wei.[132][133]

Agriculture

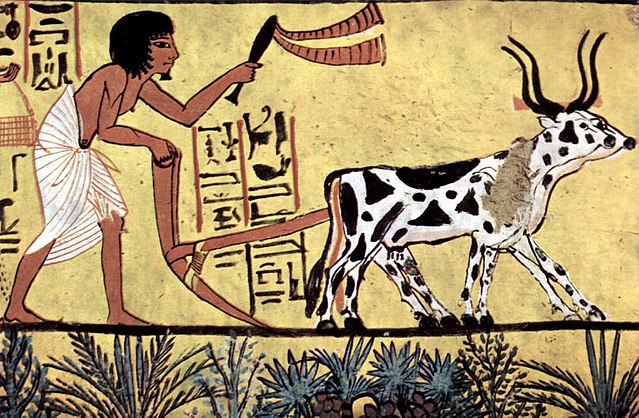

Agricultural politics in Zheng not only affected management of the land, farm operations and the harvest, but also issues of taxation, and military strength. Of the several powerful clans, the rival lineage groups (zu) of Zheng, each controlled its own lands, the primary source of community wealth and livelihood.

Zichan's policy sought to increase food production, to improve the sowing and reaping of crops, the tending of livestock.[137][138] A minister's role included agricultural management to further state prosperity,[139] as recorded in the Zhou era's Shijing.[140][141][142] Techniques and methods developed. Farm implements of stone or wood were being replaced by metal. As yoked to oxen, an iron plow increased the yield, directly causing a rise in prosperity of people and rulers.[143][144][145]

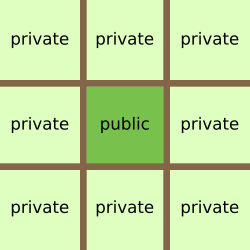

Zichan in 543 BCE reset the boundaries of farm lands and the location of irrigation ditches.[146] "The fields were all marked out by their banks and ditches."[147][148] The Mencius later described a traditional well-field system of land use,[149][150] in which eight plots of farm land surround a ninth to be tilled in common.[151][152] More probably clan lineages (zu) controlled the agricultural lands, and distributed parcels to the peasants who paid rent in kind; the remaining land was collectively cultivated to support, e.g., the lineage temple.[153][154][155]

The 543 BCE order by Zichan transformed Zheng agriculture, it "carried out such reforms as grouping houses by five, responsible for one another, and marking out all the fields by banks and ditches."[156][157][158] Clan leaders of Zheng had long dominated the farming operations on their lands, which determined power, wealth, and status.[159][160] Among the fierce inter-clan rivalries, violent revolts had irrupted to nullify any action to lessen a clan's land dominance. Moving the ditches was inherently risky for any politician (e.g., Zichan's father in 562 BCE).[161][162][163]

Tax issues arose from Zichan's reforms of farmland. Zheng's revenues were chronically short, often due to costs for defence, or to pay out tribute to powerful neighbouring states.[164] A 537 BCE reform made by Zichan increased the land tax, which drew sharp criticism in Zheng. The people reviled him, "His father died on the road, and he himself is a scorpion's tail." Zichan replied that there was no harm in the people's complaints, but that the new law benefited Zheng. "I will either live or die," he said, quoting an Ode, "I will not change it."[165][166]

Taxing land was delicate. Nuanced by the multifaceted politics of land agency and ownership, such issues were contested then in the event, and later by scholars.[167][168] In progress seemed to be a fundamental shift in the social-political evolution of farmland control. Starting confusedly in the Spring and Autumn (Zichan's era), the shift was completed more-or-less during the Warring States (475–221). Moving away from traditional communities dominated by clan lineages, land ownership devolved, parcel by parcel, to more efficiently-run holdings of "nuclear family households". Holdings that the state more easily taxed.[169][170][171][172][173]

Warfare intersected agriculture. Chariots driven in battle by aristocrats (familiar to Zichan) were starting to be supplanted by infantry.[174][175] Most foot soldiers were also farmers.[176][177][178][179] As interstate competition intensified, it pushed the ruling ministers to devote more resources for their armies. Existential demands on agriculture were made: by the state treasury and for military recruits.[180][181]

Accordingly, a state's army was supported by taxing land and its ranks were filled by drafting farmers. The early reforms by Qi state (7th century BCE) had organized its infantry into fighting units of five so as to match the social units of five composed of farming families.[182] By his agricultural and land-tax reforms starting in 543 BCE, "Zi Chan reordered the fields of Zheng into a grid with irrigation channels, levied a tax on land, organised rural households into units of five, and created a qiu levy."[183][184][185] The qiu levy here suggests the qiu troops that Lu state had mustered earlier, circa 590 BCE. Prof. Lewis concludes that Zichan followed the land tax and armed force policies of Jin and Lu states in "extending military recruitment into the countryside". These innovations were opposed and contested by the traditional elites (clan leaderships) who were "losing their privileged position" as the controlling factor in Zheng's armed forces.[186][187][188][189] Bureaucratic reforms during the Warring States would finish off the power of aristocratic clans.[190][191]

Laws of 536 BCE

Prior legal regime

In Zichan's reform of government one major focus concerned the law. Before Zichan, in each state the powerful hereditary clans, descendants of the Zhou lineage, had generally enforced their own closely-held laws and regulations.[192] "So long as the penal law remains in the secret archives of the state, those who administer the code are free to employ their own private judgement and their own moral discretion... ."[193] The contents of the law might be known only to a "limited number of dignitaries who were concerned with their execution and enforcement." Laws "were not made known to the public."[194] "When the people were kept from knowing the law, the ruling class could manipulate it as it saw fit."[195] The various clan laws, originally derived from the Zhou, were fragmented but widespread among the states.[196][197][198][199][200]

Publication

Yet the traditional governance among the city-states was then faltering and dissolving in continually changing conditions. In many regimes the ministers, by manoeuvre or usurpation, were replacing Zhou-lineage clan rulers in whose name they had acted. Ministers began to assume direct state rule of the population.[201] The Zuo Zhuan records that in 536 BCE Zheng state had its penal statutes inscribed on a bronze tripod cauldron or ding. "In the third month, the Zheng leaders cast a penal code in bronze."[202][203] These laws were made public, a first among the Eastern Zhou states.[204][205]

Au contraire, one modern view challenges this notion that before the Spring and Autumn period no state had published its laws. Prof. Creel doubted that laws were kept secret. He refers to earlier laws mentioned in very ancient writings.[206][207] Creel questioned several widely quoted passages 1) from the Zuo Zhuan which narrate how Zichan inscribed the Zheng laws on the bronze tripod ding in 536 BCE; and, 2) the story that Confucius criticized the similar publication of laws in 513 BCE by Jin, a nearby state.[208][209][210][211] Zichan in 526 BCE alludes to royal Zhou kings on punishments.[212][213] Nota Bene: Laws were purposely kept secret in the Song dynasty. "The philosophy of the Song rulers was that the laws belonged exclusively to the emperor and were never to be made accessible to the people." If known people may "circumvent" like in Zichan's day. Ming dynasty policy did the reverse, "disseminating knowledge of the law for the guidance of the people."[214][215]

Yet the story of Zichan being first in China to publish state laws remains the consensus of modern scholarship and research.[216][217][218][219][220][221] Prof. Zhao comments how the conflicted political situation of Zheng "produced the legendary figure of Zichan, arguably the most influential reformer of his age. [Zichan's] most remarkable act was placing a caldron inscribed with Zheng's legal codes in a public place in 536". Judging by the fierce reaction generated, Zichan's action must have been considered "sensational at the time".[222] A law whose text was available to those subject to it, would work to foster their awareness of proper civic conduct. Published laws served the state, 1) as a way of informing and guiding the people, and also 2) as a more effective tool of control, because it warns as well as legitimises punishment of violators. That Zichan possessed the ability to break open a new chapter in social norms was because he "had the complete support of the people of Cheng [Zheng], he enjoyed a position of full authority there throughout his life."[223][224][225][226]

Adverse reactions

For publishing the laws of Zheng, Zichan was criticised by some of his key contemporaries. It undermined the nobility, undercut their governing authority and their judicial role. Before, in making their legal judgements, the elite officials had applied to the facts their own confidential interpretation of what they viewed as the inherited social traditions, styled later 'rule by virtue'. The end result of this shrouded procedure would be very difficult to challenge.[227] By articulating and making public the legal statutes the people were better empowered to advance an opposing view of state law. Up until then ruling circles thought publishing the law would be detrimental, would open the door to public argument, bickering, and shameless manoeuvring to avoid social tradition, its time-tested moral force.[228][229] The situation was multi-sided, as political roles were changing during a surge in growth of material culture; the social tradition itself was in flux. Opening up laws to be viewed by the common people would subsequently become the trend in pre-imperial Chinese statecraft.[230]

Deng Xi of Zheng (545–501 BCE),[231] for good or ill, acquired a reputation for provoking social conflict and civic instability. A child when Zichan published the laws, Deng Xi was a controversial official of Zheng with Mingjia philosophical views.[232] Despite being aware and warned of the corrosive activities of the Mingjia, Zichan in 536 BCE had an historic bronze ding cast, inscribed with Zheng's penal laws. As Deng Xi came of age, he challenged the state and its ministers, including Zichan.[233][234][235] Some thought he studied trickery.[236] The state of Zheng put Deng Xi to death in 501 BCE according to the Zuo Zhuan.[237][238] Most probably it was not by Zichan.[239][240][241][242] Ancient documents, however, are divided as to who ordered his execution.[243][244][245][246][247] Sun comments, "But the problems he raised were not solved by his death."[248][249]

Shuxiang, a minister of Jin and personal 'friend' of Zichan, wrote a long 'letter' faulting him for making the Zheng law public. The strong letter marshalled traditional arguments against publishing the penal laws. The publicity weakened the aura of timeless truth accorded the closely-held laws of clan leadership. Confucius may later have raised such issues anew.[250][251][252][253] Harshly accusing Zichan of grave error, Shuxiang predicted future calamity for Zheng state. Responding Zichan claimed to be "untalented" and so unable to properly manage the laws with a view toward the future generations. To benefit people of Zheng alive today was his aim.[254][255][256][257][258] Issues at stake here were long debated, e.g., by philosophers of the Warring States era that followed,[259][260] and long continued.[261]

Political change

Zichan created "a break with the long-standing tradition of clan autonomy, [by] the institution of his codified law."[262] The after-effects worked to centralise legal authority in the Zheng state ministers, and to diminish the discretionary power of the several clans.[263][264][265] The legal publication also worked in various bargains and disputes to benefit the people of Zheng.[266]

More generally, the 'traditional' social conduct fostered by the li-centred rites, ancient customs once inspired by an animated world view and later associated with the Kongzi school, would be reworked, restructured and rationally integrated. After the Spring and Autumn (Zichan's era), the harsh fajia triumphed during the Qin military conquests.[267][268] Traditional social values, however, as articulated in the 'rites of li', continued to be practiced, infiltrated wide society, won political support during the Han dynasty, and eventually conjoined with or edged out legalism to "amalgamate with law".[269][270][271][272]

Yet the Kongzi doctrines explicitly fostered inner family rankings, hence the authority of the patriarch, and thus of clan-leader law, for good or ill.[273][274] A comparatist can see analogies to the paterfamilias of Roman Law.[275] Zichan in his era straddled these trends. Meticulously abiding by the rites of his office, yet innovative, deploying Zheng state law in 536 BCE to advance the people's welfare by diminishing clan law.

Sources, the text

After Zichan's legal publication of 536 BCE, it became common practice for states to selectively publish their laws. By 513 BCE Jin state, for example, had cast its laws in a bronze tripod ding for display.[276][277][278][279] In order to draft the language of the 536 Zheng legal text, an immediate source for Zichan was his own ministry's experience in prosecuting crime.

Another source for legal language commonly used in Zheng: writings privately held by the various clans. Each competing clan likely possessed its own traditions surrounding its juridical authority, its customs and rules useful to guide its own style of settling disputes.[280][281][282][283][284]

When the zu [clans] started to dissolve... people naturally needed moral principles and rules which would assimilate the customs and customary laws of different zu and be universally applied to all... .[285]

The powerful neighboring state of Jin in 621 BCE had reformed its "regulations for official affairs". Addressed were crimes, litigation, fugitives, bonds and contracts, ranking rituals, and duties of officials. The compilation of the reformed regulations were given to two officials to put into pratice.[286][287][288]

Another source existed in the written texts of the blood covenants (meng), which were negotiated between states, or between other political entities. These were produced to motivate compliance with agreements during the late Spring and Autumn when the prior era of concord and trust was disintegrating.[289][290][291][292][293]

Ancient statutes mentioned as a source. After describing Zichan's publication, the Zuo Zhuan narrates the negative response of Shuxiang, who names three statutes, each of an historical dynasty (Xia, Shang, and Zhou), as the basis of Zheng's 536 laws. Yet nothing is known of the content of these three ancient 'statutes'.[294][295][296][297]

About the lost legal text that Zheng state published in 536 BCE, a subsequent written law providea a platform for conjecture. The Fa Jing is traditionally assigned to the reformer Li Kui of Jin state circa 400 BCE, yet its authorship is questioned.[298][299] Li Kui is "regarded by Chinese historians as the first Legalist philosopher". The "published penal code attributed" to him is "not extant today" but was of "paradigmatic status", considered the "basis of the later Qin Law. and Han Law.[300] The Fa Jing contains six 'fascicles' which are titled: "Statutes on Robbery, on Banditry, on Net, on Arrest, Miscellaneous Statutes, and Statutes on the Composition (of Judgements)".[301] Another translation of these six 'fascicles': "bandits, brigands, prisons, arrests, miscellaneous punishments, and special circumstances".[302][303]

Government

Duke Mu of Zheng (r. 627–606),[304][305] was a formidable ruler. His descendants for generations led the Zheng government.[306][307] Zichan was a grandson (Gongson) of Duke Mu. Using the Zuo Zhuan as the primary ancient source, selected events of Zichan's career as Zheng leader (543–522) follow.

In 548 BCE Zichan had talked shop with a Zheng clan leader You Ji,[308][309][310] and with Ran Ming a high officer.[311] Asked by the circumspect You Ji about the way of government, Zichan offered these comments:

Governing is like farming, in that one thinks about it day and night, in that one thinks about its beginnings so as to achieve its ends, in that one acts on these thoughts from morning till evening. Do not act on what you have not thought through; do this in the same way that fields follow dividing boundaries. In this way there will be few errors.[312][313][314]

In late 543 BCE Zichan became first minister of Zheng.[315] Land reforms were started.[316]

"In taking charge of government, Zichan chose the able and employed them." Feng Jianzi was a decision maker. You Ji was "handsome and gracious, refined and learned".[319] Gongsun Hui knew neighbouring states, could read people, and write speeches. Pi Chen was a strategist of the countryside. When Zheng prepared to deal with rival states and their princes, Zichan consulted with each of these competent and tested officials. "Consequently there were rarely any failures." Such that Wei's minister called it "abiding by ritual propriety".[320][321][322] In the often dysfunctional clan nobility of Zichan's day "selecting men for office according to their ability" was unusual, as "office was commonly inherited and considered a family possession".[323] Zichan's methods increased the state's control and reach.[324]

For a state project Zichan wanted the Feng clan leader Gongsun Duan, and gave him settlements. A minister colleague You Ji complained about the gift. Zichan's reply was that he needed such clan elites to help him acchieve his goals, and not to begrudge the gift. "Let us for now give the great lineages a sense of security, and wait to see which way they go." Here, however, the overreaching Gongsun Duan turned out to quickly disappoint Zichan.[325][326]

In 542 BCE Han Hu, leader of the influential Han lineage,[327] wanted Zichan to appoint an inexperience youth he knew to a high position. Zichan declined; his lengthy reply is 'quoted' in the Zuo Zhuan. After listening to Zichan's thoughtful reasoning Han Hu praised Zichan's abilities, and said to him, "I have heard that a noble man applies himself to understand what is important and far-reaching, while a petty man applies himself to understanding what is minor and close at hand. . . . If it were not for your words, sir, I would not have understood."[328][329][330] Like Kongzi, Zichan "argued that government was a craft that required study."[331][332] Then Zichan remarked, "Men's minds are different, even as their faces are."[333]

Villagers (according to the Zuo Zhuan for 542 BCE) were debating Zheng state policies at local schools. To the suggestion that these villagers be stopped, Zichan replied, "Why should we do that?" People will freely gather and talk after work. "They are my teachers." Zichan's apparent inclination was to follow what the villagers "deem to be good policies and emend whatever they regard as bad". To diminish resentment Zichan had heard of invoking loyalty, but to use the force of authority "would be like blocking a river". A disaster follows when a river dyke breaks. It is "better that I hear criticism and let it be my medicine". The Zuo Zhuan continues, "Confucius heard this story and remarked, 'Judging from this, when people say that Zichan was not humane, I do not believe it'."[334][335][336][337] Several years later Zichan was accused of suppressing the speech and writing of Deng Xi.[338][339]

In 541 BCE two suitors, first cousins, contested marriage to the beautiful sister of Xuwu Fan. Already engaged to the younger You Chu, the woman then received a "betrothal fowl" from a superior officer Gongsun Hei,[340][341] his agent insisting on its delivery. Alarmed, Xuwu Fan told Zichan who, saying its sorrow reflected the acrimonious domestic affairs in Zheng state; Zichan left the problem to him. The cousins agreed to let the woman decide. Gongsun Hei in "elegant attire" left a gift of cloth and exited. You Chu in military dress shot an arrow to left and to right, sprang to his chariot and left. The woman watched from her chamber. She choose the "manly" You Chu. Gongsun Hei then arranged to meet You Chu. Enraged, he had intended to kill him. You Chu, aware of the danger, came with a dagger-axe. He chased Gongsun Hei to a crossroads, and there wounded him. After Gongsun Hei spoke to high officers of Zheng, telling them he acted in friendship. Zichan found "a measure of right on both sides".[342] "When both are equally justified, the younger, inferior one bears the blame."[343][344][345]

You Chu was arrested. "The great ordering principles of the state are five," Zichan said: to hold in awe the ruler, to heed his government, to revere the nobles, to serve the elders, to nurture your kin. In this case Gongsun Hei was "a great officer of the 1st degree". You Chu lifted his weapon (while the Duke was in the city) against Gongsun Hei, his cousin, his elder, his superior. Accordingly, You Chu was banished by the ruler. Zichan told him, "Do your best and set out quickly." Before, Zichan had consulted with You Ji, head of You Chu's clan, who agreed that his exile was necessary.[346][347][348] The next year Gongsun Hei took his own life. He had plotted to "remove the You lineage and take over" causing bitterness among Zheng's high officers. Zichan prosecuted Gongsun Hei, with several prior crimes included.[349][350]

In 537 BCE Zichan increased the land tax.[351]

In 536 BCE Zichan selectively published Zheng's penal laws.

In 526 BCE Zichan received a request from Han Qi the chief minister of Jin state, to purchase a certain jade ring. Zichan replied that such a ring, a "twin", was not in the state treasury. Zheng clan leaders then came forward to press Zichan to give it to Han Qi. Zichan, after considering how a "border state" keeps its sovereignty, responded with caution. His duty was not to favor the powerful (here Jin state which forced Zheng to pay it tribute), but to follow ritual propriety. Han Qi then said that he bought the matching jade ring from a merchant; however, this merchant insisted on first notifying Zheng leaders. Zichan now raised the issue of a covenant made by Duke Huan (r. 806–771 BCE) to Zheng merchants. In stressful times, with Zheng about to move its capital eastward, worthy merchants had served their state well. Han Qi withdrew his request for the ring. Often renewed, the long-ago merchant covenant stated,

"You will not rebel... and we will not force you to sell anything... or seize anything from you. You will have your profitable market and your precious goods".[352][353][354][355]

In 522 BCE Zichan "died after an illness of several months". He left his successor You Ji advice on how to run the government of Zheng. "Only one who has virtue is capable of controlling the people by means of leniency. Failing that, nothing is better than harshness". He analogised harsh laws to fire, people feared fire. Water is familiar like leniency, but people drown.[356][357][358] "When Zichan died and Confucius heard of it, he shed tears and said, 'His was a way of cherishing people that was passed down from ancient times'."[359]

In the hierarchy of Zichan's day, the nobility dominated a much larger rural population based on agriculture.[360][361][362] Yet it was a time of social transformation when the people were becoming more of a political factor, which the elites had to somehow acknowledge, or more carefully manipulate.[363][364] Zichan had earned an early reputation as a civic provider for the people's welfare.[365][366][367] In leadership style he seemed to imply an advance in political culture. Reportedly Zichan took into account the views or motivations of the nascent soldier-peasants, the common people of his Zheng state.[368][369][370][371]

Rites, ancient virtue

In 544 BCE Jizha, a prince of Wu who was regarded as a master of Zhou ritual and the arts,[372][373] undertook travel for a friendly diplomatic mission. At Lu and other states, Jizha was invited to witness the performance of music and dance, local and Zhou.[374][375] Jizha's sensitivity to moral character and ritual custom (odes and songs, dancers and musicians) endowed him with a seer's ability, a master's touch not only to refine a state's ritual ceremonies but to understand keenly its political leaders.[376][377]

Jizha came to Zheng, he met Zichan. They exchanged gifts, each acting as if the other was an old acquaintance, "it was as if the two had known each other for a long time". He told Zichan:

"Those controlling the government of Zheng are extravagant. Disaster will come soon, and government is sure to fall to you. When you take charge... conduct it cautiously by the rules of ritual propriety. Otherwise the domain of Zheng will go to ruin."[378][379][380]

By 543 BCE a dispute between two rival nobles of different clans erupted in violence and rocked Zheng state. Liang Xiao was a lineage leader,[381] also a minister of Zheng, and a notorious alcoholic. His rival Gongsun Hei led armed men of the Si clan to assault his residence which they burnt. Zheng leaders met to confer, the consensus favoring the stronger Si clan (related to the Feng clan, and to the clan of chief minister Han Hu, who thought Liang Xiao "extravagant and arrogant" and a failure).[382] Cautious, Zichan declined to take sides. In accord with ritual propriety, Zichan had the dead of the Liang clan dressed for burial. Later, three covenants were sworn, first under auspices of the Si clan, then by the Duke and his high officers at the domain's Ancestral Temple. They after "swore a covenant with the inhabitants of the capital".[383][384][385]

The Liang clan took up arms. "Both sides summoned Zichan". Not able to stop the brewing fight, he'd "follow the one favored by Heaven". In the battle Liang Xiao died. "Zichan dressed the corpse, pillowed his head on his thigh, and wailed for him." Han Hu then became furious when the Si clan threatened to go after Zichan. "Ritual propriety is the pillars of the domain," he said. "There is no greater disaster than to kill the one who has ritual propriety."[386][387][388][389]

Also in 543 BCE, as a leader of the Feng clan, Feng Juan asked Zichan for permission to hunt in preparation for a sacrifice. Zichan refused saying, "A ruler alone uses animals fresh from a hunt" for sacrifice.[390] In anger the Feng clan began to gather a force to attack him. Zichan readied to flee to Jin state. The clan leader Han Hu (Zi Pi) stopped Zichan. Instead the Feng leader fled. Three years latter, Zichan let Feng Juan return to Zheng, and gave him back his estate, his lands and accrued income.[391][392]

Later in 543 BCE Zichan became prime minister.

In 530 BCE Duke Jian died.[395][396] The Zheng state ceremony included the funeral procession. The pathway to the burial ground had to be cleared, yet it went through the You clan's ancestral temple. You Ji reluctantly permitted its clearance; however, Zichan re-routed the procession. Also the home of the supervisor of tombs would be pulled down. Otherwise, the morning funeral would not be held until midday. Zichan reasoned that the delay would hurt neither the visiting princes nor the people of Zheng. According to the Zuo Zhuan text, "Zichan understood [that in] ritual propriety, one does not pull others down in order to build oneself up."[397][398]

In 526 BCE the new Duke Ding held a state ceremony for visitors from Jin. A Zheng minister from an established family came late. The ceremony continued without accommodating him with entry to his traditional place, which drew laughter from guests. Afterwards another Zheng minister told Zichan that this was a lapse in ritual propriety and "a disgrace for you, sir." Zichan replied that making consequential mistakes in the performance of his state duties (he lists nine examples) would be for him a disgrace, but here was not. "You would do better to correct me on some other point."[399][400][401]

For 517 BCE (five years after Zichan died), the Zuo Zhuan mentions a summer meeting between the states. You Ji the successor as head of Zheng state was asked by the Jin minister about ceremony and li (ritual propriety). In reply You Ji recalled a speech by "our former high officer" Zichan. The Zuo Zhuan here presents Zichan's views at length. His speech is the ancient book's "grandest exposition of ritual and its role in ordering human life in accordance with cosmic principles", write the modern translators. About ritual propriety, Zichan said:

It is "the warp thread of heaven and earth, [on which] people make their model. . . . Warmth and kindness, generosity and affability, were made to imitate heaven's way of giving birth and fostering things. . . . For sorrow there is wailing and weeping, for pleasure there is singing and dancing, for joy there is giving and forgiving, for anger there is war and contention... . For this reason rulers were careful in their conduct and made their orders trustworthy".[402][403][404][405][406]

On Zichan's view of the guiding hand of ancient virtue,[407][408] Prof. Fung comments, "The idea expressed here... is that the practical value of ceremonials and music, punishments and penalties, lies in preventing the people from falling into disorder, and that these have originated from man's capacity for imitating Heaven and Earth." He quotes the Guoyu about these "Human interpretations of the sacrificial rites".[409][410][411][412]

Prof. Hsiao compares the core of Zichan's comments on ancient rituals and ceremonies to the teachings of Dong Zhongshu,[413] a leading scholar of the Western Han. Dong elaborated how the rites link human society to various cosmic and natural forces.[414][415][416][417]

As for participants in the Zhou-era ceremonies, distinguished verse from the Shijing may inform us about the subjective feel of the ancient li rites. "As the oldest son of a recently deceased clan head... [who] still grieves," writes Prof. Hunter, "the only moment of respite [is] during the ancestral sacrifice when his father comes down from Heaven to enjoy the offerings." The son's felt connections may be reestablished then, both to nature and community, and to his father and his ancestral wisdom.[418][419][420]

Belief, divination

Zichan's grandfather, the Duke Mu of Zheng (r. 627–606 BC), was a formidable ruler. A few years after his death, however, Zheng state faced ruin. At stake in 597 BCE was control over the land, taxes, trade, and defense, even the liberty of the Zheng people. Exhausted after a long siege of its capital by Chu state, Zheng leaders twice conducted divinations,[421] asking whether or not to further resist. In the event the victorious Chu king entered the city, but allowed its humbled Duke and Zheng state to survive.[422][423]

In 541 BCE Zichan was sent on an official visit to Zheng's powerful northern neighbor. The Prince of Jin had become very ill. An official Shuxiang told Zichan that a Jin diviner had diagnosed the Prince as haunted by two spirits, neither known to Jin scribes. Learned in ancient lore, Zichan identified the two spirits, one of a star, the other a neglected riverine ancestor.[426] Yet neither afflicted the prince, said Zichan. Instead poor management of his life-force made the prince ill: (1) of his time each day, of his emotions, his food and drink; and, (2) poor vetting of conflicts re clan origins of his harem ladies, if needed vetting by the tortoise-shell.[427][428] Shuxiang and Zichan then talked politics, e.g., about Gongsun Hei of Zheng.[429] Overhearing their conversation the Jin Prince said of Zichan, "He is a noble man and widely versed in the things of the world", then "rewarded him lavishly".[430][431] Yet the Jin Prince evidently did not take the cure.[432]

In 536 BCE rumors of the ghost of a controversial politician gripped the populace of Zheng. It started perhaps when "someone dreamed that Liang Xiao walked in armour" and threatened to kill the head of the Si lineage on a certain day, and the next year the Feng lineage head. Liang Xiao had been a troubled, important minister of Zheng, an alcoholic; he died in 543 BCE during urban fighting between the Si clan and the Liang clan. "The people of Zheng spooked one another with tales of Liang Xiao". On the day so foretold the Si clan chief died. Later the Feng chief fell dead. City inhabitants became frightened, then terrified. To "sooth the people" and calm the ghost, Zichan established positions for the family of Liang Xiao.[433][434][435]

The haunting stopped. His colleague You Ji questioned, challenged Zichan, who replied: "When a ghost has a place to go, it does not become an evil spirit." As to the official positions for the unfit family members who lacked propriety, Zichan appraised that as a minor violation. "I did it to please the people," he said. "We who are in charge of government [must] curry favour, for lacking favour, we will have no credibility. Without credibility, the people will not follow us."[436][437]

"Whatever his own beliefs about the existence of these ghosts, Zichan shows here a canny ability to maintain the balance of power among noble lineages and to manipulate public opinion by appearing to appease the spirits of his enemies."[438]

Later Zichan was asked about whether Liang Xiao was still able to be a ghost. His powerful family, Zichan replied, had "held the handle of government for three generations" so that his very strong vitality might make a capable aura-soul. His violent death could trigger a ghost, which may then possess another person, becoming a demon.[439] Zichan in his conduct of state affairs, paid respect to popular religious values and loyalties. Yet Zichan apparently also kept abreast of the nascent attitude about Heaven, that appropriate behaviour should conform to moral norms as understood among human beings, rather than to unknowable mysteries.[440] Yet Zichan demonstrated concern for the afterlife of ancestors, including ghosts.

In 535 BCE the Jin Prince was ill for three months. Zichan was told by a Jin official that the Prince "dreamed of a tawny bear" perhaps vengeful. Zichan identified the bear as the spirit of Gun, father of the sage-king Yu. The Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties all made him offerings. Jin state then made the spirit an offering. The Prince rallied, and then gave Zichan two cauldrons.[441][442][443]

In 525 BCE a comet appeared. Pi Zao, Zheng's Master of Divination, warned Zichan of a great fire. "If we offer a pouring vessel and a jade ladle, Zheng is certain not to have a fire." Zichan disagreed, refused.[444][445] In 524 BCE fires burned in neighbouring states. Pi Zao, supported by Zheng nobles, requested a sacrifice but Zichan refused, saying to a minister, "The Way of Heaven is far away. . . . How can we know anything of it? In truth this fellow only talks a lot. [Yet by luck] he might be right... ." However, the "great turtle shell" and ancestral tablets were moved. Invocators addressed water and fire spirits. As the fires approached Zichan ordered safety measures across the city. The military "took up positions along the path of the fire". Houses burned, whose owners were afterwards given tax relief and building materials. For three days there was wailing, and the city markets did not open.[446][447][448][449]

Zichan told Jin state officials later in 525 BCE, "we were fortunate enough not to perish". The sometimes-allied Jin leaders had "divined with turtle shell and milfoil,"[450] when the fires hit Zheng.[451]

Prof. Kaizuka reads Zichan's comments on the unknowable Way of Heaven as indicative of a budding rationalism emerging in late Spring and Autumn China. In distinguishing the human world as "what can be known" and the will of Heaven as "incomprehensible", Zichan's "attitude contained the seeds" of reliance on reason. "This development spelt the end of the unity of religion and government in the joint sacrificial community which formed the city-state". It also reflects the split between his written laws and the obscurity of clan rule.[452][453]

In 523 BCE a great flood hit Zheng. By the capital's south gate, a pool formed where dragons fought. People asked for an expiatory sacrifice, which Zichan refused. "When we fight, dragons take no notice, so why should we... when dragons fight? [T]he water is their home."[454][455][456] Modern writers offer conjectures about Zichan here.[457][458][459]

Prof. Hsiao, in a discussion of "ancient religious practices honoring gods and spirits", and of the declining "role of the irrational" during the Warring States period, comments on Zichan (Tzu-ch'an) per the two episodes (the comet and the dragons) above.

"In the Spring and Autumn Period there occasionally appeared some individuals capable of casting off superstition. Tzu-ch'an of the state of Cheng refused to believe in spirits. When Pei-tsao [Pi Zao] told him that a certain comet portended a conflagration, he replied: 'The way of heaven is distant, while the way of man is near. We cannot reach to the former; what means have we of knowing it?'"[460][461]

In Zheng a text attributed to Zichan discussed the soul and survival. Humans each have two souls: the material p'o exists from sperm; after birth the aerial hun appears from breath, little by little. In life joined, the two separate after death. The material "follows the body into the tomb" and the aerial subsists free. Each soul seeks to "support its spectral life" hence the living care for the dead, who become their guardians. If starving, however, the soul turns to brigandage to survive.[462][463][464]

The royal Zhou's cultural dominance continually receded during this Chũnqiũ period. The predominately rural people of the vassal states[465] began to align more with the fruitfulness and vitality of their farm lands, rather than the fading charisma of capital aristocrats and clan leaders.[466][467] Hence the declining status of urban shrines to the Zhou lineage. The countryside "altars of soil and grain" began to gain popularity.[468][469][470] In 524 BCE because of the great fire, Zichan had "made a great altar of earth and performed exorcisms in four directions".[471][472][473]

Interstate relations

The early ambition of Zheng's political leadership seemed similar to other Zhou vassals, to strengthen the state and expand its territory. Initially triumphant, it became the leading state c. 700 BCE. Such status did not last. Zheng's strategic position had powerful neighbours who hemmed it in on all sides, blocking its potential for competitive expansion.[474]

Zichan acted like a highly skilled realist in state-to-state politics. When the State of Jin tried to interfere in Zheng's internal affairs after the death of a Zheng minister, Zichan was aware of the danger. He argued that if Zheng allowed Jin to determine the minister's successor, Zheng lose its sovereignty. He eventually convinced Jin not to interfere in Zheng affairs.[475]

In 548 BCE Zheng state invaded Chen. Zichan jouneyed to Jin to defend it.[476][477]

In 546 BCE an interstate meeting was convened in the state of Song, to negotiate a durable peace, chiefly between a northern league headed by Jin, and the southern league of Chu. The Covenant of Song resulted.[478][479][480][481] In the unsteady armistice or balance of power, Zichan had better opportunities to exercise his statecraft, and became known for his political skills.[482]

In 539 BCE the Duke Jian of Zheng accompanied by Zichan visited Chu state. The ambitious King Ling recited a hunting ode in a Chu ceremony. Zichan then made preparations, and in marshland south of the Yangzi river the King, the Duke, and Zichan went out hunting.[483]

In 538 BCE the King of Chu asked Zichan, "Will Jin grant overlordship of the princes to us?" After describing the confused internal affairs of the Jin ruling class, Zichan replied in the affirmative. "Will the princes come to us?" By the Covenant of Song (546 BCE),[484] and considering the prevailing political conditions in the various states, their rivalries and alliances, Zichan again was affirmative. The King said, "In that case, is there nothing I want that I cannot have?" "One cannot seek fulfillment at the expense of others. If you share the desires of others, you will succeed in everything," said Zichan.[485][486] Despite this "warning about the dangers of overreaching",[487] King Ling later that year "showed off his lack of moderation in the presence of all the princes." Zichan then remarked, "The Chu King is excessive and stubborn in the face of remonstrance. He will last no longer than ten years."[488]

In 536 BCE Shuxiang a Jin minister sent a harsh letter to his 'friend' Zichan, to condemn his publication of Zheng's penal laws. As a result of this unforced blunder by Zichan, Shuxiang told him that Zheng state will likely perish in the near future.[489]

Later in 536, while traveling to Jin state an embassy of Chu intended to cross over the territory of Zheng. Chu and Jin were the very powerful neighbours, Jin to the north and Chu to the south. The embassy was met at the border by Zheng officials including Zichan, who required them to swear an oath to do no harm within Zheng's borders. This was standard diplomatic protocol as proscribed in ritual texts.[490][491][492]

In 531 BCE the Chu army occupied the weak state of Cai. Jin state was unable to aid Cai. Years earlier Zichan had criticized Cai's leader for negligence and arrogance, wondering if he could "manage to die a natural death". Now Zichan said, "Cai is small and disobedient, while Chu is large and lacking in virtue. Heaven will abandon Cai in order to make Chu overfull".[493]

In 529 BCE an arrogant and aggressive King Ling of Chu, who by patricide had seized his throne, came to grief. Faced with the death of his sons, and political rebellion on all sides, from both the princes and the multitude, the king took his own life.[494]

Also in 529 BCE Zichan attended the conference of states at Pingqiu called by Jin state. There he successfully disputed with Jin officials.[495][496]

Zichan's general view was to allow in most cases the common people of Zheng "free discussion of his policies" in their local schools.[497] He excepted, however, discussion of relations with neighboring states, which too often would lead to 'hot-headed' notions that courted disaster. This matter required the subtle use of reason, yet here Zichan is said to have "failed to shake off the prejudice of the nobleman."[498]

Remove ads

Viewed in philosophy

Summarize

Perspective

Zichan's political thinking is known from his work as minister of state. The kernels of his thought are found in the historical record. His near contemporary Confucius mentioned him. In the centuries following his death, several philosophers of the Warring States period, and later, referred to his exemplary state actions, suggesting contexts for understanding his points of view. For in his lifetime Zichan's public life had resulted in an acknowledgement, whether bad or good, of how his career and recorded sayings had defined his reputation, which endured in ancient Chinese political thought.[500][501][502]

Era of conflict & flux

During the course of the Spring and Autumn period when Zichan was minister "the old order broke down". The people "were bewildered by the lack of standards for settling disputes and maintaining harmonious relationships." The old clan-based hereditary houses, still nominally in power, were losing their social status while appointed state ministers became the new dominant authorities. The resulting regimes were often conflicted, divided and fragmented internally. War between the states also increased in frequency. The changing and confused statecraft of the era no longer enjoying traditional sanction. State upheavals and social instability seemed to compel a search for innovation, for a fundamental change.[503][504]

Zichan is "depicted in the [Zuo Zhuan] as one of the wisest men of his time, and also as a leading statesman in the small ancient state of [Zheng], which was under constant threat of extinction by its powerful neighbours". Evidently in his person Zichan practised the traditional li ceremonies and elite virtues of the fading Zhou dynasty (whose ideals were endorsed by Confucius). In his political craft, however, Han-era historians could see him as able to anticipate the later Legalist philosophy of the Warring States period, i.e., skillful in the promulgation and enforcement of newly articulated laws. Such enforced obedience to state-wide standards would better secure the political control of events by the ministers.[505][506]

The Zuo Zhuan quotes at length from a speech attributed to Zichan. His thoughts tended to separate the distant domains of Heaven and the near domain of the human world. He argued against superstition and acted to curb the authority of the Master of Divination. He counselled the people to follow their reason and experience. Heaven's way is distant and difficult to grasp; while the human way is near at hand.[507][508][509][510]

Confucius

Kongzi and Zichan

In the pages of the Lunyu, Confucius speaks well of Zichan. In his personal conduct and attitudes, Zichan is described as demonstrating the traditional virtues Confucius advocated.

The Master said of Tsze-ch'an that he had four of the characteristics of a superior man: in his conduct of himself, he was humble; in serving his superiors, he was respectful; in nourishing the people, he was kind; in ordering the people, he was just."[512][513]

The Lüshi Chunqiu paired Confucius and Zichan (who in this translation is called 'Prince Chan'). Both are praised as talented state ministers who led their countries to significant achievements. Both became regarded as successful governors who directed others to accomplish administrative tasks.[514]

There were, of course, issues on which Zichan and Confucius did not agree. Confucius, then only 15, did not comment when Zichan caused the laws of Zheng to be published in 536 BCE.[515][516] Yet when later in 513 BCE the neighbouring city-state of Jin published its laws, Confucius clearly made known his strong opposition. Such actions undercut the traditional authority of the Zhou-dynasty kings and the city-state nobles who ruled in their name, which scheme of governance were idealized in Confucian doctrine.[517][518] In modern reinterpretations, however, Confucius may often appear to foster the people's welfare over such authority.[519][520][521]

Another area of disagreement touched on the human capacity to draw insights from observing society. Confucius taught about an ability to discern, from common repetitive civic events, the distant future. By careful observation, change in the customary rites of a dynasty can indicate the course of its social history many generations hence.[522][523][524][525] Zichan, however, at a decisive moment of political conflict, was known to confess that he was not talented enough to make such future predictions. So he merely tailored his decision carefully only for the people of Zheng then living.[526]

Zichan's regard for the popular welfare was nonetheless limited, culture-bound to the era's customary rankings.[527][528] Yet records of his policy decisions showed that he'd take into account the interests of commoners. Zichan's career seems largely in keeping with the beneficial social values taught later by Confucius.[529]

Like Zichan, Confucius was "born in [this] period of great political and social change", a centuries-long revolutionary "upheaval caused by forces beyond his control and already under way." Yet Confucius drew upon the Zhou cultural inheritance. Prof. Creel notes scholarly speculation about contemporary sources that Confucius drew upon in developing his teachings. The Zuo Zhuan quotes at length "several statesmen who, living shortly before Confucius... expressed ideas remarkably like his." They were "advanced in their thinking".[530]

The Han historian Sima Qian in his text the Shiji lists Zichan as one of the six teachers of Confucius.[531][532]

Zichan and Kongzi

Confucius (551–479 BCE) was almost 30 when Zichan died. That is, "the formative period of Confucius' thinking" were years that "coincided exactly with the time" of Zichan's civic career, which embodied "rule by a worthy minister".[533] Although himself for most years an unsuccessful office seeker, Confucius survived as an independent, private teacher, and became a revered educator. His teachings later accepted as an orthodoxy, he also established in China the literary tradition of personal authorship. Confucius thus left us his views in assembled writings and created a school of disciples, unlike Zichan who instead actively served his city-state in government office.[534]

Zichan has been appraised as practicing the ethics of the Confucian ideal ruler before it was taught by the sage, i.e., as Zheng leader Zichan was a forerunner to Confucian doctrine, before Confucius came of age.[535] In comparison, the influential politician Zichan often upheld the state's ancestral sacrifices and public ceremonies, endorsing their privileging status in Zheng's civic affairs. He cultivated his own inner life according to the moral compass of the rites of Li, so as to guide his public actions by authoritative ethics.[536][537][538]

Zichan, in his career as an active statesman, has been judged favorably over the instructor Confucius, who seldom carried the burden of public office.[539] Anachronistically,[540] a part of Zichan's role was somewhat comparable to the scholar official who later as 'Confucian' magistrate, subordinate to and in the name of a dynastic emperor, administered and adjudicated.[541][542]

The Zuo Zhuan, following more or less a quasi-Confucian point of view, documents many episodes featuring the activities of Zichan as the minister of Zheng. In general, Zichan is presented in a favourable light.[543]

Mencius

The Mengzi of Mencius, fourth century (Warring States period), refers to Zichan. A perplexed disciple questions Mencius about the conduct of Shun, one of the legendary sage kings. Shun's hostile parents and family had lied to him. Shun mistakenly believed them, but he did not reveal a corrupt nature thereby. Shun believed their lies because of his regard for his parents. A life of virtue is then discussed.

Mencius compared sage king Shun here to a story about Zichan, when he had believed a dishonest servant. Zichan gave his groundkeeper a live fish to keep in a pond; instead he cooked and ate it. He later told Zichan the fish was alive and swimming in the pond. Zichan was happy that the fish "found his place". Hearing this from Zichan, the servant mocked his reputation for wisdom. But not Mencius, who concluded: "Thus a noble man may be taken in by what is right, but he cannot be misled by what is contrary to the way".[544][545][546]

Yet Mengzi in another episode disapproved of Zichan's 'small kindness'. The head of the Zheng government Zichan, it was reported, used to carry people across the rivers in his own carriage. Mengzi wrote, "He was kind but did not understand how to govern." Better it would be to get the bridges in good repair so the people not need wade across the rivers.[547][548]

Shen Buhai

In 354 BCE Shen Buhai[549] (c. 400–337 BCE)[550] became chancellor of Han state. Before 403 Han had been one of three rebellious, clan-ruled constituent provinces of Jin (W-G: Chin); it received state status from the Partition of Jin.[551][552] In 375 BCE Han conquered and annexed its neighbour Zheng (W-G: Cheng),[553][554] where Shen Buhai had been born.

"The most famous man of Cheng was the statesman Tzu-ch'an [Zichan], who controlled its government from 543 B.C. until his death in 522. . . . In some respects the role of Tzu-Ch'an in Cheng resembled that which Shen Pu-hai would play in Han two centuries later."[555]

Shen Buhai's "talent in statecraft" enabled him to "live quite well" during the Warring States period. Then the seven states were engaged in a fierce, all-consuming competition to survive. To become "strong in war" required "becoming strong in organisation, population, and production". Effective rulers benefited from ministers or advisers with such skill and experience. A state's prestige was in fact celebrated by presence at court of political philosophers whose statecraft had been verified by success.[556]

Shen Buhai's contemporary was Shang Yang the legalist.[557][558] In their comparison, Han Fei distinguished two styles of government. The use of law (fa) to control people's conduct (which might be used to restrict activity to agriculture and war). The use of technique (shù)[559] to manage through tact and formality, the personnel of government ministries (bureaucratic administration).[560][561][562][563] In this sense Shen Buhai did not follow legalism (fa) per se, but emphasized rather the use of technique (shù).[564][565][566]

Zichan could be said to be an early example of employing both evolving styles. Yet the rapid development of statecraft and expansion of government bureaucracy between the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States was so comprehensive,[567][568][569] that Zichan's methods and techniques of administration sometimes seemed primitive to later philosophers.[570][571]

Shang Yang

Acclaimed by his adherents as the best minister at implementing legalism during the Warring States period, Shang Yang (c. 390–338 BCE) did not mention Zichan in his writings. A major theme in Shang's politics was focus on agriculture and war, to the exclusion of all else,[572] to strengthen his Qin state in order to dominate all its rivals.[573][574][575]

Zichan, of a different age, was not so narrowly focused. He aspired to foster the virtues of traditional rites, by fa and shù he kept Zheng state rather fit,[576] with diplomacy he parried rival states, his government made room for merchants, the people of Zheng discussed his policies, along the way he accumulated a reputation in good standing.[577][578][579]

Xunzi

A follower of Confucius, Xunzi (c. 310 BCE – after 238 BCE) advanced the doctrine. He crafted a philosophical framework (filtered by Taoism and Legalism) to nest the teachings of the Rújiā. Differing with Mencius, Xunzi concluded that our human nature was not good to start, but we needed to be guided by education and nourished by the rites of li.[580][581][582]

In discussing the life of Confucius, Xunzi mentioned 'an official act of Zichan' that contributed to a precedent Confucius chose to follow.[583]

In his first few days as prime minister of Lu, Confucius ordered the execution of a well-known person. His followers questioned the harsh act. In affirming his decision, Confucius gave five reason that justified putting a man to death (e.g., his "speaking falsely and arguing well" or his doing "what is wrong and making it seem smooth"). Confucius is said to have had a short list of historical examples (given in the Xunzi) of justified executions, included as the sixth and last: "Zichan executed Deng Xi".[584][585][586]

Also about Zichan, Xunzi wrote; "Zichan was a person who won over the people, but he never went as far as making government work."[587] Xunzi's opinion may be attributed to Zichan in his traditional role as a Zhou-era ruler who established a personal model for his people to cultivate, and acted directly like a benevolent father. This role opposed the legalist conception where the ruler held authority, whose connections to the people all passed through competent officials who administered the laws, which alone set the standards of behavior. Official enforcement of law caused the government to work.[588][589]

Han Feizi

Once taught by Xunzi (a Confucian), Han Feizi (c. 280–233 BCE) became a critic of Kongzi, and the premier philosopher of legalism.[590][591][592] His life was difficult, it ended in tragedy. Of the nobility of Han state,[593] his gift for political affairs was early recognized despite his stutter.[594][595] Yet the Duke of Han ignored him, then sent him as an envoy to Han's enemy Qin state. Han Fei's writings were already greatly admired by Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BCE), its powerful ruler.[596] The legalist Li Si,[597] a classmate of his youth, was now Qin's chief minister. Li Si claimed Han Fei was a spy. He was jailed.[598][599][600]

1. Zichan appears in the text Han Feizi (written by Han Fei and others). Three different passages refer to Zichan's effective method of handling 'litigants' or 'suspects' to get at the truth. Zichan "separated them and never allowed them to speak to each other. Then he inverted their words and told each the other's arguments and thereby found the vital facts involved in the case."[601][602] Zichan here anticipates such methods [shù] advocated by Shen Buhai.

2. Han Fei observed that "when prestige in a royal house is low" ministers utter few "upright words". If "self-seeking" prevails, few will seek merit or serve "the public". As an example Han Fei writes, "when Zǐ Chǎn sincerely advised the monarch" he was "angrily rebuked" by his father Zǐ Guó.[603][604][605] Han Fei later added: Ziguo told Zichan his loyalty to the state was "an act sharply different" from other ministers. If the sovereign is "worthy and enlightened" he will listen to you. If not, you are left "estranged" and "endangered", and "your father, too".[606][607]

3. Han Fei can hold Zichan in high esteem. In the composite book Han Feizi a state policy to please the people is decidedly rejected. In illustrating the people's folly, Zichan is placed in equal stead to Yu, a legendary sage king and founder of the Xia dynasty.[608][609][610] "Yu profited the whole world, [Zichan] preserved the state of [Zheng], yet both men suffered slander... ." The people failed to understand them. The Han Feizi concludes that an able ruler knows: (a) "the wisdom of the people is not sufficient to be of use" for governing, (b) "to try to please the people [is the cause] of confusion", and (c) the people "are of no help in ensuring good [political order]".[611][612][613]

Apparently Han Fei here opposes a Confucian teaching, i.e., that a contented yet lively people indicates good government.[614][615][616] Yet Zichan's career is more 'proto-Confucian' than not.[617] Although Zichan did raise the land tax against popular opposition,[618] he also knew the political advantage of a public favorable (even if irrationally) to state leaders.[619] In putting down a clan revolt, it was with public support.[620] He did know how to punish.[621] Although the people initially complained of his reforms, a few years later they praised him.[622] By publishing the Zheng's penal laws, the people benefitted.[623] Zichan was widely considered a popular minister.[624] Interpretations of the Han Feizi, however, include nuanced framing about the issue of public welfare.[625][626][627][628][629]

4. In a passage that criticizes Zichan, the Han Feizi carefully (if paradoxically) rejects both benevolence as a government policy, and the practice of personal virtue in its officials. In grasping the two handles of government (rewards and punishments), the ruler should judge solely by objective standards, not seeking to show benevolence but justice. Rewards are for merit, punishment for crime; officials must be satisfied accordingly. Furthermore, the state alone has authority to determine the standards; officials may not disagree or counter state policy by employing a personal moral 'wisdom'.[630][631]

5. Shortly before death Zichan advised his successor as prime minister to skillfully punish offenders to preserve good order for the people.[632][633] The Han Feizi quotes Zichan, "You must use strict measures to govern the people. Fire appears fierce, so people are rarely burned, water appears weak, so people often drown".[634][635]

Sang Hongyang

Sang Hongyang (152–80 BCE), politician and policy maker of the Han dynasty, considered an "undisguised legalist", achieved the high office of Imperial Secretary.[636] Son of a merchant, known for his skill in production and trade, tax and revenue, Sang Hangyang played a key role in the Discourses on Salt and Iron, which dealt with state monopolies. A dispute with rival bureaucrats resulted in his death.[637][638][639]

As against Confucians, the legalist Sang held that "the people's characters are fixed by natural endowment and cannot be alterred". Challenging his foe's claims that a ruler's good example will likely sway others to better conduct, Sang referred to Zichan of Zheng. His exemplary career was not enough to curb the crimes of unruly clan chiefs. "Even such sages and worthies as... Tzu-ch'an (Zichan) were yet unable to transform the evil and specious characters of... a Teng Hsi (Deng Xi)."[640][641]

Deng Xi vs. Zichan

The Liezi gives two stories about Deng Xi's rivalry with Zichan.[642] Both such events occur in the state of Zheng, and appear to illustrate fundamental life principles.

The Liezi text

Obscure in origin the Liezi became widely admired, a book of "stories and philosophical musings" collected over centuries.[644][645][646] Questions about its authenticity has resulted in a "considerable secondary literature". Yet during the Tang dynasty the Liezi was deemed the third of three Taoist classics, after the Tao Te Ching and the Zhuangzi.[647][648]

Its nominal author Lie Yukou (fl. 400 BCE) was "a real or imaginary hero of Chuang-tzu's anecdotes". In this dating of Lie Yukou, he reportedly hailed from Zichan's own state of Zheng.[649][650][651]

In the early Taoism of Zhuang Zhou, "Lieh Tzu could ride upon the wind... and return in fifteen days."[652][653] The notion of a mystic gnosis by the Taoist perfect man is presented in "the famous mystic Lieh-tzu, [yet] treated by Chuang-tzu somewhat suspiciously as a man inclined to use his spiritual power to display himself and to control the world through his charismatic magic."[654]

Rivalry and fate

From chapter six, "Endeavour and Destiny", this episode first addresses the rivalry in Zheng state between Zichan and Deng Xi (WG: Teng Hsi). Its second half (omitted here) discusses how to manage life and death, suffering and change.

Graham's translation differs in detail from Wong's version.[655] Of the rivalry, telescoped renderings are given here, first Graham's, then Wong's.

Deng Xi liked to argue what was ambiguous. He wrote a code of laws, yet he attacked the chief minister, Zichan. The state adopted the laws, Zichan accepted the criticism, then suddenly had Deng Xi executed. "They could not have acted otherwise."[656]

Deng Xi liked to find fault, to stir up conflict among his colleagues in the government. Zichan ruled Zheng and to control crime enacted stricter laws. All were agreeable except Deng Xi. He attacked Zichan and his laws, so that officials split into two hostile camps. Without warning, Zichan had Deng Xi executed. "Things could not have happened otherwise... given the natural dispositions of the two men."[657]

The modern consensus for dating events in ancient China seems to place Zichan's death in 522 BCE, and to place Deng Xi's execution in 501 BCE, twenty-one years later.[658][659] Yet the Liezi makes a telling exemplar of their rivalry, which ends in the sudden execution.[660][661] The Lushi Chunqiu states:

When Prince Chan governed Zheng, Deng Xi strove to disrupt things. . . . Thus, wrong was taken to be right, and right was taken to be wrong. With no standard of what was right and wrong, what was permissible and impermissible varied each day. . . . The state of Zheng fell into complete chaos, and the populace clamored. Prince Chan, troubled by this turn of events, had Deng Xi executed.[662]

Opinions among scholars vary. "Car, si bon de le disent les auteurs Han, ils insistent bien sur le fait qu'il sut châtier. Une seule fois, c'est vrai, mais c'est bien le caractère unique de l'exécution de Deng Xi... qui la rend, tout la fois, admissible, efficace et nécessaire."[663][664]

Hedonistic brothers

This episode is from chapter seven, entitled "Yang Chu", a chapter considered markedly different than the rest of the Liezi.[665][666] Yang Zhu (c. 440 BCE – c. 360 BCE) founded the philosophical school of Yangism,[667][668] which flourished for a time during the Warring States period. Contra the more optimistic Confucius who focused on social norms and community service, Yang Chu held negative views of life, yet taught an individual's cultivation of the ego. Such inner personal development was coherent with Taoism. Although Taoism did not teach simple hedonism, nor did Yang Chu,[669][670] 'his' Liezi chapter clearly adopts a hedonism.[671][672] Elsewhere in the Liezi, however, hedonism is explicitly criticised.[673][674] In this episode, the attack on Zichan also seems to strike at Confucius.[675][676][677]

Zichan's success as Zheng minister led him to ponder his two wayward brothers, each a mark of failure in his family. He confided his unease with Deng Xi, who encouraged him to 'put things straight'.

His elder brother Chao was a drunk, with his own rice-beer brewery; his constant intoxication was wrecking his health and fortune. Younger brother Mu, a libertine, kept many young beautiful women; obsessed with his sex life, he was careless of all else.

Zichan met with them. Reason and foresight, morals and reputation are more important to the good life, he said, than feelings of the moment. If so, he'd offer them responsible, well-rewarded positions.

Mocking him, his brothers said they'd chosen to follow the true path of their human desires. Better, they said, than his way of pandering to the world and doing violence to his natural self. Pleasure and happiness beat reputation and a disagreeable life. If all followed nature, no need for government.