Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Stephen Kotkin

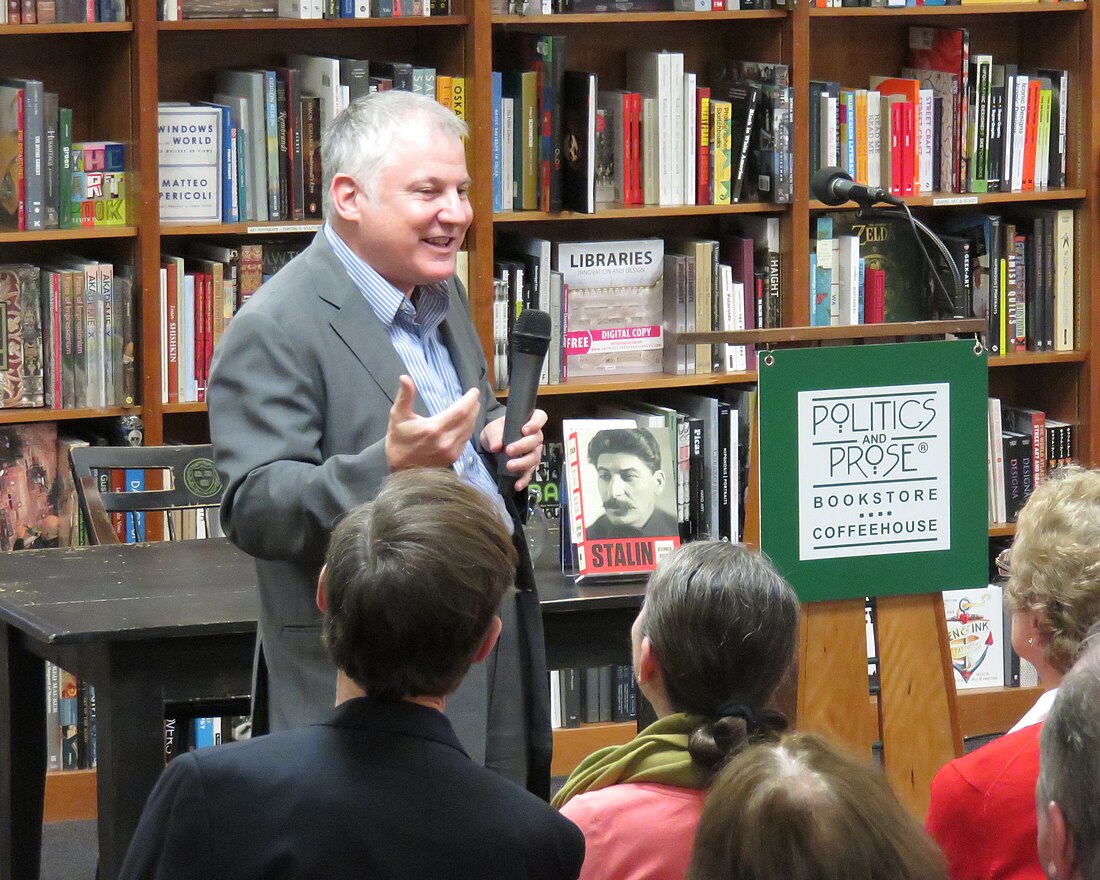

American historian, academic and author (born 1959) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Stephen Mark Kotkin (born February 17, 1959)[1] is an American historian, academic, and author. He is the Kleinheinz Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University.[2] For 33 years, Kotkin taught at Princeton University, where he attained the title of John P. Birkelund '52 Professor in History and International Affairs; he took on emeritus status from Princeton University in 2022. He was the director of the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies and the co-director of the certificate-granting program in History and the Practice of Diplomacy.[3] He has won a number of awards and fellowships, including the Guggenheim Fellowship, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. He is the husband of curator and art historian Soyoung Lee.[4]

Kotkin's most prominent book project is his three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin: The first two volumes have been published as Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 (2014) and Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 (2017), and the third volume remains to be published.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Kotkin was born in New Jersey, the third son of Jay Kotkin, a factory worker of Belarusian-Jewish descent, and Joanne Korolewicz,[citation needed] a cook and art teacher.[5] His father's family emigrated from Vitebsk in the Russian Empire (now Belarus).[6] He grew up in New York City.[7]

He graduated from the University of Rochester in 1981 with a B.A. degree in English. He studied Russian and Soviet history under Reginald E. Zelnik and Martin Malia at the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned an M.A. degree in 1983 and a Ph.D. degree in 1988, both in history.[8] Initially, his PhD studies focused on the House of Habsburg and the History of France, until an encounter with Michel Foucault persuaded him to look at the relationship between knowledge and power with respect to Stalin.[9]

Starting in 1986, Kotkin traveled to the Soviet Union, conducting academic research and receiving academic fellowships. He was a visiting scholar at the USSR Academy of Sciences (1991) and then at its descendant, the Russian Academy of Sciences (1993, 1995, 1998, 1999 and 2012). He was also a visiting scholar at University of Tokyo's Institute of Social Science in 1994 and 1997.[10]

Remove ads

Academic career

Kotkin joined the faculty at Princeton University in 1989. He served as the director of the Russian and Eurasian Studies Program for thirteen years (1995–2008) and as the co-director of the certificate program in History and the Practice of Diplomacy from 2015 to 2022.[8] He is now the Kleinheinz Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Author

Summarize

Perspective

Kotkin has written several nonfiction books about history as well as textbooks. Among scholars of Russia, he is best known for Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization which exposes the realities of everyday life in the Soviet city of Magnitogorsk during the 1930s.[11] In 2001, he published Armageddon Averted, a short history of the fall of the Soviet Union. He is a frequent contributor on Russian and Eurasian affairs and he also writes book and film reviews for various publications, including The New Republic, The New Yorker, the Financial Times, The New York Times and The Washington Post. He also contributed as a commentator for NPR and the BBC.[10] In 2017, Kotkin wrote in The Wall Street Journal that Communist democide resulted in the deaths of at least 65 million people between 1917 and 2017, stating: "Though communism has killed huge numbers of people intentionally, even more of its victims have died from starvation as a result of its cruel projects of social engineering."[12]

His first volume in a projected trilogy on the life of Stalin, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 (976 pp., Penguin Random House, 2014) analyzes his life through 1928, and was a Pulitzer Prize finalist.[13] It received reviews in newspapers,[14][15] magazines,[16][17] and academic journals,[18][19] The second volume, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941 (1184 pp., Penguin Random House, 2017) also received several reviews,[20][21] magazines,[22] and academic journals[23][24] upon its release. In these books, among other things, Stephen Kotkin suggested[25] that Lenin's Testament was authored by Nadezhda Krupskaya. Kotkin pointed out that the purported dictations were not logged in the customary manner by Lenin's secretariat at the time they were supposedly given; that they were typed, with no shorthand originals in the archives, and that Lenin did not affix his initials to them;[26][27] that by the alleged dates of the dictations, Lenin had lost much of his power of speech following a series of small strokes on December 15–16, 1922, raising questions about his ability to dictate anything as detailed and intelligible as the Testament[28][29] and that the dictation given in December 1922 is suspiciously responsive to debates that took place at the 12th Communist Party Congress in April 1923.[30] However, the Testament has been accepted as genuine by many historians, including E. H. Carr, Isaac Deutscher, Dmitri Volkogonov, Vadim Rogovin and Oleg Khlevniuk.[31][dubious – discuss][32] Kotkin's claims were also rejected by Richard Pipes soon after they were published, who claimed Kotkin contradicted himself by citing documents in which Stalin referred to the Testament as the "known letter of comrade Lenin." Pipes also points to the inclusion of the document in Lenin's Collected Works.[33]

The third and final volume, Stalin: Totalitarian Superpower, is set to be published in "several years", according to Kotkin in November 2024.[34] He is currently writing a multi-century history of Siberia, focusing on the Ob River Valley.[10]

Remove ads

Published works

Remove ads

Political views

Summarize

Perspective

Stephen Kotkin supports a centrist view of "normal politics," based on the premise that "problems arise at the extremes, the far left and the far right that don't recognize the legitimacy either of capitalism or of democratic rule of law institutions."[36] Several socialist media outlets have accused Kotkin of ideological bias against the Bolshevik Revolution, pointing out that Kotkin referred to American journalist and socialist John Reed, author of Ten Days that Shook the World, as "former Harvard cheerleader" in his book Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928.[37][38] When speaking about the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine in an interview with Foreign Affairs, Kotkin suggested that a serious threat of regime change in Russia could ultimately motivate Vladimir Putin to stop the war. Kotkin also described Donald Trump's foreign policy regarding the war in Ukraine as unpredictable, and said he thought it was unlikely that Trump would succeed in becoming an autocrat, given the existing checks and balances in the United States' political system.[39]

In an article in Foreign Affairs magazine, Kotkin proposed a series of policies to better prepare the American economy and society for international confrontation with China and Russia. He called for the expansion of STEM education, stating that it makes little sense to admit students " lacking the universal language of science, engineering, computers, and economics" and that students would be "limited to majoring in themselves and their grievances." He likewise called for the expansion of community colleges and trade schools. In the article Kotkin also stated his belief that drastic cutbacks of environmental regulations and cutting housing construction subsidies would allow the free market to construct housing faster, and also called for mandatory national service for young Americans.[40]

Remove ads

References

Works cited

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads