Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Autonomy for the region of Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace within the Ottoman Empire was a concept that arose in the late 19th century and was popular until around 1920. The plan was developed among Macedonian and Thracian Bulgarian émigrés in Sofia and covered several meanings. It was adopted and given prominence by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee.

Art. 1. The goal of BMARC is to secure political autonomy for the Macedonia and Adrianople regions.

Art. 1. The goal of SMAO is to secure political autonomy for the Macedonia and Adrianople regions.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The idea of autonomy was promoted during the 1880s, by diverse political parties in Bulgaria and in Eastern Rumelia, aimed at "national unification of Bulgarian people".[1] This scenario was partially facilitated by the Treaty of Berlin (1878), according to which Eastern Rumelia, Macedonia and Adrianople areas were given back from Bulgaria to the Ottomans, but especially by its unrealized 23rd article, which promised future autonomy for unspecified territories in then European Turkey, settled with Christian population.[2] This trend emphasized the principle of popular sovereignty, and appealed for a democratic constitution and further decentralization and local autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. In general, an autonomous status was presumed to imply a special kind of constitution of the region, a reorganization of gendarmerie, broader representation of the local Christians in all the administration, etc.

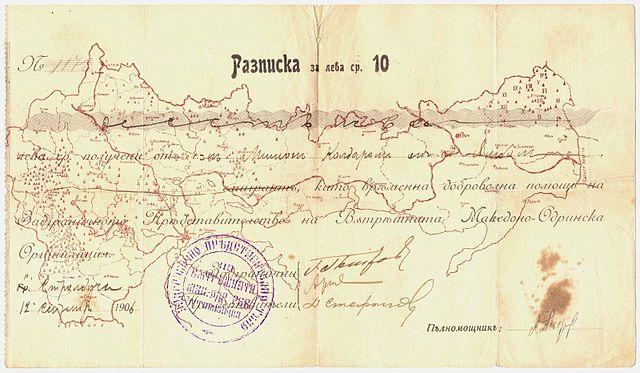

The concept was popularized in 1894 by the first statute of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) with its demand for political autonomy of the Macedonia and Adrianople regions.[1] Initially its membership was open only for Bulgarians and it opposed the Greek, Serb, and Bulgarian irredentist claims towards Macedonia.[3] It was active in Macedonia, but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople).[4] At the eve of the 20th century, on the initiative of Gotse Delchev, it changed its exclusively Bulgarian character and opened it to all Macedonians and Thracians regardless of their nationality.[5] The Organization gave a guarantee for the preservation of the rights of all national communities there. Those revolutionaries saw the future autonomous Macedono-Adrianople Ottoman province as a multinational polity.[6] Another Bulgarian organisation called Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committee (SMAC) also had as its official aim the struggle for autonomy of Macedonia and Adrianople regions. Its earliest documents referring to the autonomy of Macedonia were the Decisions of the First Macedonian Congress in Sofia in 1895.[7]

However, there was not a clear political agenda behind this idea and its final outcome, after the expected dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.[1] By many activists, from SMAC especially, and in IMRO such as Hristo Matov and Hristo Tatarchev, the autonomy was seen as a transitional step towards unification of both areas with Bulgaria.[8][9][10] This outcome was based on the example of short-lived Eastern Rumelia. The successful unification between the Principality of Bulgaria and this Ottoman province in 1885 was to be followed. On the other hand, IMRO leaders like Gotse Delchev, Gyorche Petrov, Petar Poparsov, Yane Sandanski, Dimo Hadzhidimov etc. and their supporters strongly resisted Macedonia’s incorporation into Bulgaria, and saw the autonomy as a first step towards a independent Macedonia which would join a future Balkan Federation.[10][11][12][13][14][15] Serbia and Greece were totally opposed to that set of ideas while Bulgaria was ambivalent because of SMAC and those within IMRO who supported the annexation by Bulgaria.[16]

According to an editorial in the Pravo newspaper called "Political separatism" (June 7, 1902), which itself was based in Sofia and was close to the IMRO, the idea of Macedonian autonomy was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity. As the ideas of the Treaty of San Stefano were already unrealistic, the autonomy was the only alternative to the partition of Macedonia by the Balkan states and the assimilation of its Bulgarian population by Serbs, Greeks, etc.[17] The text implies that the integrity of Macedonia means conservation of the unity of the Bulgarian people. Thus, paradoxically, through the realization of autonomy, it is projected Bulgarians to remain united, even though politically divided.[18]

In 1905 the newspaper Revolyutsionen list issued in Sofia and redacted by Hadzhidimov, expressed the opinion of the Serres leftist group about the autonomy as follows:

" They, the Supremists, represent a complete negation of the Internal Organization – there is an abyss between it and them. First of all, against the goal of the Organization of Autonomous Macedonia and its motto "Macedonia for the Macedonians", they put some "autonomous Macedonia" with a disguised motto “Macedonia for Bulgaria”. “Autonomous Macedonia” is understood by the organization as an independent state, which will enter as a separate member into the federation of the other states of the Peninsula; and the Supremists understand it as a transitional form to "San Stefano Bulgaria", which is feasible only for those who do not see further than their noses."[19]

During the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and the First World War (1914–1918) the organisations supported the Bulgarian army and joined to Bulgarian war-time authorities when they took control over parts of Thrace and Macedonia. In this period autonomist ideas were abandoned and the direct incorporation of occupied areas into Bulgaria was supported.[20] These wars left both areas divided mainly between Greece, Serbia (later Yugoslavia), and the Ottoman Empire (later Turkey). That resulted in the final decline of the autonomist concept. After that the combined Macedonian-Adrianopolitan revolutionary movement split into two detached organisations – the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation and the Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation.

In 1919 the so-called Temporary representation of the former United Internal Revolutionary Organisation founded by former members of the IMARO, issued a memorandum and send it to the representatives of the Great Powers on the Peace conference in Paris. They advocated for autonomy of Macedonia as a part of a future Balkan Federation. Following the signing of the Treaty of Neuilly and the partition of Macedonia, the activity of the Temporary representation faded and in 1920 it was dissolved. The former IMRO revolutionary and member of the Temporary representation Hadzhidimov wrote in his brochure "Back to the Autonomy" in 1919:

"This idea, nevertheless, remained a Bulgarian idea until it disappeared even among the Bulgarians. Neither the Greeks, nor the Turks, nor any other nationality in Macedonia accepted that slogan... The idea of autonomous Macedonia was developed most significantly after the creation of the Internal Macedonan revolutionary Organization which was Bulgarian in respect of its members and proved to be well decided, of great military might and power of resistance. The leadership of the Macedonian Greeks could not rally under the banner of such an organization which would not, under any circumstances, serve Hellenism as a national ideal... Undoubtedly, since the Greeks of Macedonia, the second largest group following the Bulgarians, had a position like this vis-a-vis the idea of autonomy, the latter could hardly anticipate success."[21][22]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads