Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

First statute of the IMRO

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

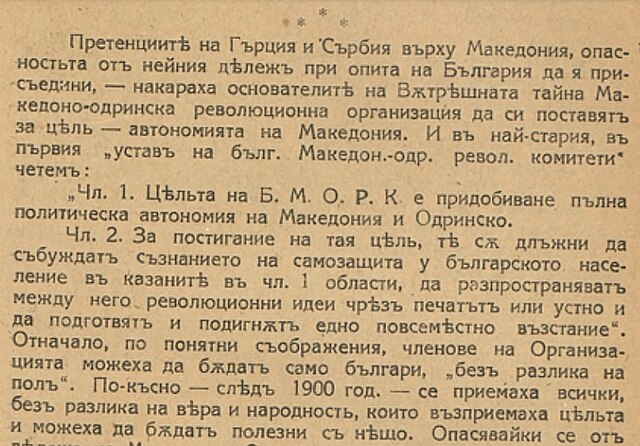

Remove ads

In the earliest dated samples of statutes and regulations of the clandestine Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) discovered so far, it is called Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committees (BMARC).[note 1][11][12][13] These documents refer to the then Bulgarian population in the Ottoman Empire, which was to be prepared for a general uprising in Macedonia and Adrianople regions, aiming to achieve political autonomy for them.[14][15] In thе statute of BMARC, that itself is most probably the first one,[16][17] the membership was reserved exclusively for Bulgarians.[18] This ethnic restriction matches with the memoirs of some founding and ordinary members, where is mentioned such a requirement, set only in the Organization's first statute.[19][note 2] In fact, the founders of IMRO were sympathetic to Bulgarian, but hostile to the Serbian nationalism,[20] which led them to establish in 1897 a Society against Serbs.[21] The organization's ethnic character is confirmed by the lack of any mention of Macedonian ethnicity.[22] The name of BMARC, as well as information about its statute, was mentioned in the foreign press of that time, in Bulgarian diplomatic correspondence, and exists in the memories of some revolutionaries and contemporaries.[23]

Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees

Chapter I. – Goal

Art. 1. The goal of BMARC is to secure full political autonomy for the Macedonia and Adrianople regions .

Art. 2. To achieve this goal they [the committees] shall raise the awareness of self-defense in the Bulgarian population in the regions mentioned in Art. 1., disseminate revolutionary ideas – printed or verbal, and prepare and carry on a general uprising.

Chapter II. – Structure and Organization

Art. 3. A member of BMARC can be any Bulgarian, independent of gender, ...

Due to the lack of original protocol documentation, and the fact its early organic statutes were not dated, the first statute of the Organisation is uncertain and is a subject to dispute among researchers. The dispute also includes its first name and ethnic character, as well as the authenticity, dating, validity, and authorship of its supposed first statute.[24] Moreover, in North Macedonia, any Bulgarian influence on the country's history is a source of ongoing disputes and sharp tensions, thus such historical influences are often rejected by Macedonian researchers in principle. Certain contradictions and even mutually exclusive statements, along with inconsistencies exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization, which further complicates the solution of the problem. It is not yet clear whether the earliest statutory documents of the Organization have been discovered. Its earliest basic documents discovered for now, became known to the historical community during the early 1960s.

The revolutionary organization set up in November 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki changed its name several times before adopting in 1919 in Sofia, Bulgaria its last and most common name i.e. Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[25] The repeated changes of name of the IMRO has led to an ongoing debate between Bulgarian and Macedonian historians, as well as within the Macedonian historiographical community.[26] The crucial question is to which degree the Organization had a Bulgarian ethnic character and when it tried to open itself to the other Balkan nationalities.[27] As a whole, its founders were inspired by the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary traditions.[28] Such activists believed that Slavic Macedonian society was reproducing the Bulgarian National Revival with a time lag.[29] The situation was similar in Adrianople Thrace.[30] All its basic documents were written in the pre-1945 Bulgarian orthography.[31] The first statute of the IMRO was modelled after the statute of the earlier Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC).[32] IMRO adopted from BRCC also its symbol: the lion, and its motto: Svoboda ili smart.[33] All its six founders were closely related to the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki.[34] They were native to the region of Macedonia, and some of them were influenced from anarcho-socialist ideas, which gave to organisation's basic documents slightly leftist leaning.[35]

The first statute was drawn up in the winter of 1894. In the summer of the same year, the first congress of the organization took place in Resen. At this meeting, Ivan Tatarchev was elected as its first head. The draft of the first statute was approved there, while the drafting of its first regulations was commissioned.[36][37] The occasion for convening this meeting was the celebration on the consecration of the newly built Bulgarian Exarchate church in the town in August 1894.[38] It was decided at the meeting to preferably recruit teachers from the Bulgarian schools as committee members.[39] Of the sixteen members who attended the group’s first congress, fourteen were Bulgarian schoolteachers. Schoolteachers were en masse involved in the committee's activity, and the Ottoman authorities considered the Bulgarian schools then "nests of bandits". On the eve of the 20th century IMRO was often called by the Ottoman authorities "the Bulgarian Committee",[40][41] hence the Ottomans considered it to be Bulgarian in its national orientation,[42] while its members were designated as Comitadjis, i.e. "committee men".[43]

Remove ads

Memoirs' controversy

Summarize

Perspective

Contradictions, inconsistencies and even mutually exclusive statements exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization on the issue.[44] According to the founding member Hristo Tatarchev's пemoirs, there were created two structures with the first statute from 1894: an organization and its central committee. He mentions as their names "Macedonian Revolutionary Organization" (MRO) and a "Central Macedonian Revolutionary Committee" (CMRC) and clarifies that the word "Bulgarian" was subsequently dropped from their names. It is not clear, if its first name was simply MRO, how the definition "Bulgarian" was dropped from it subsequently. However, Tatarchev notes that he doesn't remember the first name very clearly.[note 3] On the other hand, according to the founding member Gyorche Petrov, initially the IMRO was not called an "Organization", and this term was introduced after 1895.[45] According to another founding member, Petar Poparsov, the Organization was designated initially a "Committee", and its first name was "Committee for acquiring the political rights of Macedonia, given to it by the Treaty of Berlin".[46] Per Tatarchev, the founders of the IMRO had Zahari Stoyanov's memoir about the April Uprising of 1876, in which the statute of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC) was published, which they took as a model for the organization's first statute.[47] According to Tatarchev, the Adrianople region was included in the organization's program in 1895, while this decision was implemented practically in 1896.[48][49] However, per Hristo Kotsev (1869-1933) Dame Gruev commissioned him to start the construction of the committee network in Adrianople region in 1895.[50] Thus, in September 1895, the first revolutionary committee was founded in Bulgarian Men's High School of Adrianople.[51]

According to Poparsov, the first statute's swatch was sent to be printed in Romania, where it burned down in a fire and its publication failed.[46] However, according to the IMRO activist Lazar Gyurov (1872-1931), the first statute and regulations were printed in a very limited quantity in Thessaloniki after 1894. According to Gyurov's claims, he had hidden one copy each of the statutes and regulations, but he did not manage to keep them because they fell apart due to poor storage conditions. It is known that the first statute was prepared by Petar Poparsov and was adopted at the beginning of 1894, and according to some reports, the first regulations were developed by Ivan Hadzhinikolov either in the same year or in 1895. The data presented by Gyurov has raised the question of whether the foundational documents of the Organization were really printed in Thessaloniki for the first time. It is known also that another early statute and regulations adopted in 1896, were printed in Sofia in 1897, by Gyorche Petrov and Gotse Delchev.[52] According to Gyorche Petrov, before the drafting of the second statute and regulations in 1896, there were available others, which were still in use, that suggests there were earlier printed statutes and regulations after all.

The first statute allowed the membership only for Bulgarians and this is confirmed by Tatarchev in his memoirs from 1936 as follows: "it was allowed that every Bulgarian, from any region, could be a member",[53][54] as well as in the memoirs of other revolutionaries.[55] According to Hristo Matov, although the first statute allowed the membership only to Bulgarians Exarchists, in practice the leaders of the Organization didn't prohibit the membership of Patriarchists, Uniates and Protestants of all local nationalities,[56][57] According to Ivan Hadzhinikolov, membership was open to everyone from Macedonia.[58] According to Tatarchev's recollections, the decision about the change of the statute, so that not only Bulgarians could be members of the organization, was taken in 1896.[59] Per the SMAC activist Vladislav Kovachev the first statute of the IMRO allowed the membership only for Bulgarians within a special article. According to the revolutionary Nikola Altaparmakov (1873-1953), a revolutionary committee was founded in Thessaloniki in 1893, and per its first statute, any Bulgarian could be its member.[60] Dimitar Vlahov maintained that initially, the organization worked only among Bulgarians who belonged to the Bulgarian Exarchate.

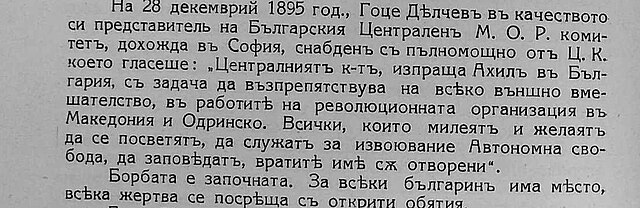

Per Iliya Doktorov (1876-1947) initially the organization had a nationalist character and only Bulgarians had the right to be members of it, but this ethnic restriction lasted until 1896.[61] According to Georgi Bazhdarov, who also confirmed the statute of BMARC as a first one, the Organization was opened to other nationalities besides Bulgarians after 1900.[62] In the memoirs of Alekso Martulkov, it is claimed that the original statute of the organization allowed only Bulgarians as members. This situation was changed in a new statute in 1896.[63] Per Bulgarian anarchist Spiro Gulabchev (1856 – 1918), in the mid-1890s, arose the "Bulgarian Macedonian Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee", which, according to its statute and regulations, was a Bulgarian nationalist organization.[64] According to Dimitar Popevtimov (1890-1961), the organization was initially called the BMARC, and only Bulgarians were accepted as its members, per its first statute from 1894.[65] Per Peyo Yavorov, the first IMRO statute was almost a copy of the old Bulgarian revolutionary statute and contained a special article according to which only Bulgarians were its members. According to Nikola Zografov in 1895 Gotse Delchev was supplied with a power of attorney from the name of the BMARC and sent to Sofia to propagate the struggle for autonomy that was open to every Bulgarian. Per Hristo Silyanov in the minds of the founders of the organization, it was Bulgarian in its ethnic composition, and its member, according to the first statue, could be "any Bulgarian".[66] Krste Misirkov states in his brochure On the Macedonian Matters (1903) that the “Bulgarian committees” were led by "Bulgarian clerks", aiming the creation of “Bulgarian Macedonia".[67]

Remove ads

Bulgarian Macedonian–Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committees

Summarize

Perspective

Discovery of the statute of BMARC

The basic documents of the Оrganization under its earliest names, i.e. Bulgarian Macedonian Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC) and Secret Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Orgazation (SMARO) were nearly unknown until the 1960s to the historical researchers.[68] In 1955, the historian Ivan Ormandzhiev published in Sofia the undated statute of the SMARO, which he dated from 1896.[69][70] In 1961, Macedonian historian Ivan Katardžiev published undated statute and regulations discovered by him, naming the organization BMARC, which he dated from 1894. The discovered documents are kept since then at the Institute of National History in Skopje.[71][72] Originals of the statute and the regulations of BMARC were found in 1967 also in Bulgaria.[73] According to the statute of the BMARC, membership of the Organization was allowed only for Bulgarians. Per Katardžiev the statute of the BMARC was the first statute and that was the first official name of the IMRO. According to him, the organization never bore as an official name the designation "Macedonian Revolutionary Organization" (MRO).[74] Some international, Bulgarian and Macedonian researchers have adopted his view that this was the first statute, i.e. the first official name of the organization.[75][76][77][78]

Macedonian views

BMARC

Katardžiev claimed that this was the first statute of the organization and under this name, it existed from 1894 until 1896 when it was changed to Secret Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (SMARO). In 1969, the name BMARC as the first one, was officially promoted as position of the Macedonian historical community in the second volume of the first ever three-volume History of the Macedonian people, as well as in its one-volume edition, in 1970.[79] Per Gane Todorovski from its very name could be concluded this was initially an organization primarily of the Bulgarian population in Macedonia and Adrianople areas.[80] Thus, per historian Krste Bitovski this was not only the first preserved statute but the original statute of IMRO.[81] According to Manol Pandevski the basic program document of the Organization was published in 1894 under the name "Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committees", and so it even was not called an organization.[82] Katardžiev, confirmed there was an overlapping of the texts of the statutes and regulations of BMARC and these of SMARO, and it was clear that when drafting these of SMARO, those of BMARC were used. Later that conclusion was confirmed, while corrected statute and rules of the BMARC were discovered in Bulgaria, which are practically drafts of the basic documents of the SMARO.[83]

Revisionist turn

In 1981, the Macedonian historiography for the first time publicly dissociated itself from the thesis advocated by Katardziev for the name BMARC in the first volume of the two-volume publication Documents for the struggle of the Macedonian people for independence and for a national state.[84] In 1999 this view has been finally revised by Blaže Ristovski in his "History of the Macedonian nation". He practically adopted the position of some from his Bulgarian colleagues, the first name of the Organization was MRO.[85] Today many historians in North Macedonia question the authenticity of the statute of BMARC or reject its relation to the IMRO. They claim that IMRO-activists had allegedly an ethnic Macedonian identity,[86][87] while the designation Bulgarian is thought to had rather a religious connotation then.

Those who accept the existence of the statute claim the term Bulgarian was used ostensibly for tactical reasons because the organization's activity was concentrated primarily on the Bulgarian Exarchist population. Others insist that the founders of the organization were then under the influence of some kind of Bulgarian nationalist propaganda.[88][89] Or, as the historian Dimitar Dimeski claimed, even without to mention the name "BMARC", per its first statute, the organization had a nationalist character. It was the result of intolerance, external influence and lack of experience.[90] On the other hand, the existence of the Adrianoplolitan part in the name of the Organization, which is undoubtedly Bulgarian, points per Macedonian scholars, to the existence of some kind of supra-ethnic organizational system.

An example for this revisionist turn is the historian Vančo Gjorgiev. In 1997 Gjorgiev himself confirmed the authenticity and the dating from 1894 of the statute of BMARC.[91] Gjorgiev also published the Statutes and the Regulations of BMARC translated from Bulgarian into Macedonian language in 2013.[92] However in 2021, he has rejected all this, claiming that allegedly not a single document written from any activist of the Organization has been found so far, containing the name of BMARC.[93]

Bulgarian views

IMRO as Bulgarian organization

Bulgarian historians see the statute and the regulations of BMARC as a confirmation of the Bulgarian ethnic character of the organization.[94][95][37] The aim of the Committees per Art. 2 of their statute was to raise the consciousness for self-defense among the Bulgarian population in both regions in order that there be one single uprising in them.[96] The definition Macedonian then had a regional meaning,[97] while the ideas of separate Macedonian nation were supported only by a handful of intellectuals.[98] They insist also, except the national designation "Bulgarian" in the name, another part of it is related to the then vilayet of Adrianopole, whose Bulgarian population has not being contested in North Macedonia today.[99] Also, apart from the fact the statute allowed the membership only to Bulgarians, the regulations contain an oath which also confirms its Bulgarian character.[100] Such an interpretation stems not only from the fact all documents of the Organization were written in the Bulgarian language, but also from the wide acceptance of Bulgarians, as from the Bulgarian principality (including Eastern Rumelia), as well as from Ottoman Thrace (Vilayet of Adrianople) into the leadership of the Organization. Such an example was the case with the affiliation of the Bulgarian Secret Revolutionary Brotherhood to IMRO in 1899. Its leader Ivan Garvanov, who was from Bulgaria proper, became the head of the IMRO in 1902, and architect of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising.[101] This corroborates the fact that the Macedonian revolutionaries then did not insist on any own ethnic difference with regard to the rest of the Bulgarians.[102]

MRO

In 1969 the Bulgarian historian Konstantin Pandev promoted the view that the designation BMARC lasted from 1896 until 1902, when it was changed to SMARO, a view adopted by some international and Bulgarian historians.[103][104][105][106] Until then, Bulgarian historians shared Katardžiiev's opinion that the designation BMARC was used between 1894 and 1896. Today some Bulgarian researchers assume the first unofficial name of the organization during 1894-1896 was Macedonian Revolutionary Organization or Macedonian Revolutionary Committee.[107] However, despite the name MRO is present in some contemporary sources,[108][109][110][111] neither statutes nor regulations, or other basic documents with such names have not yet been found.[112] Other Bulgarian researchers suppose that the founding statute of the IMRO still hasn't been discovered or it hasn't survived.[26] Thus, the first preserved statute of the organization is that of the BMARC.[113] Other Bulgarian historians do not accept the view of Pandev and continue to adhere to that of Katardziev, i.e., the first statutory name of the organization from 1894 was BMARC.[114][115][116] Bulgarian researchers also maintain that Katardžiev himself had some manifestations when he publicly claimed the IMRO revolutionaries had Bulgarian self-awareness.[117][118][119]

Authorship dispute

According to some Bulgarian and Macedonian researchers, the author of BMARC's statute was Petar Poparsov.[120][121] Other Bulgarian historians assume that the authors of the statute were Gotse Delchev and Gyorche Petrov.[122] Per Peyo Yavorov, Gotse Delchev participated in a congress of the Organization, which adopted a statute, almost a copy of the old Bulgarian revolutionary statute. It contained a special article according to which only Bulgarians were accepted as its members. According to Yavorov, Delchev voted in support of this article in question, which he believed was chauvinistic. Later, when the circumstances changed, Gotse was the first to insist that this article be amended, and this is what happened.[123][124] In Ivan Hadzhinikolov's memoirs, is written that Petar Poparsov was assigned to draw up the first statute. In his memoirs, Dame Gruev recounts the founders grouped together and jointly drew up a statute modeled after the statute of the revolutionary organization in Bulgaria before the Liberation.[125] Gyorche Petrov also tells about the writing of the statutes in his memoirs. According to him, initially a short statute drafted by Dame Gruev was in force. It was decided to draw up a new complete statute and regulations. Petrov do it in Sofia, together with Delchev.[126]

Periodization dispute

The periodization of the Internal Organization's names is a matter of debate while both the BMARC and SMARO statutes were not dated. As mentioned above, it is believed by some Bulgarian historians that in 1896 the first and probably unofficial name MRO was changed to "BMARC", and the organization existed under this name until 1902. It is believed by them too, the first statute's swatch burned down in a fire in Bucharest, and was irrevocably lost. However, when Pandev promoted this view in 1969, the memoirs of Lazar Gyurov, where he confirmed the publication of the first statute in 1894 in Thessaloniki, were still unknown.[127] There are still Macedonian historians who acknowledge the existence of the name "ВMARC" in the very early period of the Organization (1894–1896), but generally today in North Macedonia it is assumed that between 1894 and 1896 it was called MRO, while in 1896–1905 period the name of the organization was "SMARO".[128] On October 10, 1900, the newspaper "Pester Lloyd", published in retelling form excerpts from the captured by the Ottoman authorities statutes of the Bulgarian Macedonian Revolutionary Committee, i.e. BMARC. On October 13, the Greek newspaper "Imera" published the same material.[23]

On the other hand, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Skopje Gottlieb Para (1861-1915), in his report of 14.11.1902, attached a document in translation, which he designated as the new statute of the revolutionary organization. This document bears the title: "Statute of the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization". It is identical to the document issued in 1902, according to Pandev, as well as with the statute, which according to Katardziev was compiled in 1897.[129] At the same time the Serbian Consul General in Bitola Mihajlo Ristic wrote on January 25, 1903 that until the beginning of 1902, the work of the Committee had a purely Bulgarian character, while the local Serbs and Greeks were feared from its activity. At the end of 1902, however the Committee-members began to turn to all Christians for cooperation, regardless of their nationality.[130] Also, even in 1895, Gotse Delchev was supplied with a power of attorney and sent to Sofia, as a representative of the "Bulgarian Central Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee".[131] Based on the early 2000s discovery, that the cover of the BMARC rules were dated 1896, the problem when the BMARC regulations were printed, is claimed to be solved by the Bulgarian historian Tsocho Bilyarski.[132][133] However, Hadzhinikolov points out that he prepared it in 1895.[134] According to Tatarchev, in 1894 arose the need to develop an internal rulebook and this was done by Hadzhinikolov at the end of the same year.

In this way, the question of the time of creation and adoption of the rules remains open. According to the memoires of Dimitar Voynikov (1896-1990), when Delchev visited Strandzha Mountain in 1900, the changes in the statute of SMARO were already fact and were discussed at a meetings with the local IMRO-activists, where his father was present.[135] Also, Macedonian historians point to the fact that a copy of the "SMARO" statute was kept in London since 1898.[136] In 1905 the organization changed its name to Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO), which is indisputable.[137]

Membership and ideology

Per Article 3 of the statute of BMARC: "Membership is open to any Bulgarian, irrespective of sex, who has not compromised himself in the eyes of the community by dishonest and immoral actions, and who promises to be of service in some way to the revolutionary cause of liberation."[138][139] The next statute of SMARO opened membership in the Organization to every Macedonian or Adrianopolitan, regardless of their ethnic origin. The subsequent statute of 1905 declared that anyone living in European Turkey could be a member of IMARO, regardless of sex, faith, nationality, or belief.[140] The IMRO members saw then the future of Macedonia as a multinational community, and did not aim at a separate Macedonian ethnicity, but understood "Macedonian" as an umbrella term, encompassing the different nationalities in the area.[141] The common political agenda declared in the BMARC, SMARO and IMARO statutes was the same: to achieve political autonomy of both regions. While this leftist idea was taken aboard by some Vlachs, as well as by some Patriarchist Slavic-speakers, the new statutes, which Delchev and Petrov had prepared early in 1897, and which Delchev revised in 1902, failed to attract other groups.[note 4][142] For them the IMRO remained the Bulgarian Committee.[143][144][145] According to Hristo Tatarchev, founders' demand for autonomy was motivated by concerns that a direct unification with Bulgaria would provoke the rest of the Balkan states and the Great Powers to military actions. In their discussion the Macedonian autonomism was seen as a step for an eventual unification with Bulgaria.[146] According to the revolutionary Dimo Hadzhidimov this idea remained a Bulgarian, until it disappeared even among the Bulgarians, while any other nationality didn't accept it.[147] In 1911, it passed a new decision according to which again only members of Bulgarian nationality would be admitted to the organization. Although this change was not included in the next basic documents of the Organization, it became an informal principle.[148][149][150]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

In 2015, a civil association "BMARC Ilinden-Preobrazhenie" was registered in Bulgaria. Among its founders were scientists, historians, journalists and descendants of Bulgarian historical figures from the regions of Macedonia and Southern Thrace.[151] In 2016, a monument to the fallen revolutionaries from Macedonia and Thrace was uncovered in Sofia. On the left side of the monument is written the abbreviation BMARC (БМОРК), denoting the first name of the revolutionary organization.[152]

In 2018, in relation with the campaign for the change of the constitutional name of the then Republic of Macedonia, the Bulgarian Cultural Club in Skopje initiated the idea to include the name of BMARC in the preamble of the Macedonian constitution.[153] On the other hand, in 2023 the founder of VMRO-DPMNE, Lyubcho Georgievski, proposed to include the Bulgarians in North Macedonia as a separate ethnic minority in the preamble of its constitution, based on fact that such people were members and founders of the historical BMARC. Moreover, this was actually a mandatory condition of the EU to the accession of the country into the Union.[154]

However, these ideas were rejected. According to historian Vanċo Gjorgiev, since Bulgarians were removed from the Organization's alleged first statute once, there is no place for them in the country's current constitution too.[155] In North Macedonia, the acknowledgement of any Bulgarian influence on its history and politics is very undesirable, because it contradicts the post-WWII Yugoslav Macedonian nation-building and historical narratives, based on a deeply anti-Bulgarian attitudes, which still continue today.[156][157][158] On that occasion, the Macedonian film director Darko Mitrevski has concluded that there is no more mythologized term in Macedonian history than the name of IMRO, but behind this historical myth is hidden actually the original designation of BMARC, an organization founded by people with Bulgarian consciousness.[159][160]

See also

- Internal Revolutionary Organization

- Unity Committee

- Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee

- Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee

- Bulgarian People's Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization

- Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation

- Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United)

- Bulgarian Action Committees

External videos with opinions of Macedonian public figures, historians, etc., on the issue

- Excerpt from an interview of the journalist Vasko Eftov with Prof. Katardžiev in the program Vo Centar called "Kade odi Macedonija?" Archived 2023-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Vo centar with Vasko Eftov about the issue with the foundation of the IMRO Kako Blaze Koneski stana Falsifikatorot od Nebregovo!?

- Vo centar with Vasko Eftov about the issue with he foundation of the IMRO Васко Ефтов: ВМРО е создадено од декларирани Бугари Archived 2024-05-04 at the Wayback Machine.

Remove ads

Gallery

- Statute of the BRCC used as a model for the IMRO's first statute.[161] This statute was drawn up in Bucharest in 1872. Its authors were Vasil Levski and Lyuben Karavelov. In the middle is depicted a lion, standing enraged over a broken Ottoman flag and torn rings of iron chain.

- Cover of the statute of the BMARC. Above is an inscription "statute" with the name of the organization below. In the middle is a picture with a seated woman. In her right hand she holds a flag where it is written "Svoboda ili smart". Below is depicted a lion wearing a crown.[162][132]

- A book about Gotse Delchev, issued in 1904 by Peyo Yavorov. Per him there was a congress of the IMRO, which adopted a statute, with a special article according to which only Bulgarians were accepted as its members. This issue was changed in the next statute.[166]

- The magazine "Macedonia" (1922) where Georgi Bazhdarov claims on p. 5, the first name of the organisation in its first statute was BMАRC.[169]

- "The Struggle of the Macedonian People for Liberation" (1925) where Dimitar Vlahov maintains on p. 10 that initially, the organization worked only among Bulgarians who belonged to the Bulgarian Exarchate.[170]

- "The Construction of Life" (1927), authored by Nikola Zografov (1869 - 1931). Per his view espoused on p. 58 in 1895 the Organization already bore the name BMARC and the struggle for autonomy was open to every Bulgarian.[171]

- Hristo Tatarchev's Memoirs about the creation of the IMRO, which according to his opinion espoused on p. 103, was first called MRO and CMRC. Published in Sofia by Lyubomir Miletich in 1928.[172]

- The newspaper Yeni Asır, providing info about one of the voivodas of the Bulgarian chetas Yane Sandanski, who was also a leader of the centralist faction of the Bulgarian committee (1908).[173]

- The cover of the first volume of the book The Liberation Struggles of Macedonia by Hristo Silyanov, per whom in the minds of the founders of the organization, it was Bulgarian, and its member, according to the first statue, could be "any Bulgarian".[174]

- The initial page from the manuscript of Spiro Gulabchev, dedicated on the IMRO, where he criticizes the organization as a Bulgarian nationalist society that was named in its first statute and regulations as BMARC.

- Cover of the unpublished book "Notes and Reflections on the Macedonian Nation" where Dimitar Popevtimov cited in 1959 art. 3 from the statute of the BMARC, claiming this was the initial name of IMRO.

- On October 10, 1900, the newspaper "Pester Lloyd", published in retelling form excerpts from the statutes of the BMARC.

- Cover of the book "My Participation in the Revolutionary Struggles" from 1954. The author Alekso Martulkov claims the first statute from 1894 contained a special Article, which permitted the membership in the Organization only to Bulgarians.

- Monument of the fallen for the freedom of Macedonia and Thrace in Sofia. On the first line at the top left is the abbreviation BMARC (БМОРК), denoting the first name of the revolutionary organization.

Remove ads

Notes

- Bulgarian: Български македоно-одрински революционни комитети (БМОРК), Macedonian: Бугарски македонско-одрински револуционерни комитети (БМОРК)

- This formulation was understood then primarily as referring to the Bulgarian Exarchists, who in those conditions were synonymous with the name "Bulgarians". Apart from them, the Bulgarian Uniates from the Kukush region and the Bulgarian Protestants from the Razlog region were among the first to be drawn into the IMRO. Both, the former and the latter were distinguished by their Bulgarian national self-awareness. For more see: Дмитрий Олегович Лабаури (2008) Болгарское национальное движение в Македонии и Фракии в 1894-1908 гг. Идеология, программа, практика политическои борьбы. БАН, ISBN 9789543223176, стр. 137.

- In his memoirs from 1928 Tatarchev, when mentioning Organization's first name and structure, noted that he does not remember them very clearly, making the remark: "as far as I can remember." So far, no statutes or other basic documents with a similar name have been discovered from this period. According to Macedonian specialist Ivan Katardziev, the Organization never bore an official name MRO. In Tatarchev's own recollections from 1936 he maintains that in the first statute, the membership was allowed for every Bulgarian, and that the possibility for membership of other nationalities was open in 1896 in a new statute. Tatarchev also clarified that the word "Bulgarian" was subsequently dropped from the name of the Organization, because the autonomous principle, required the founders to avoid everything that aroused suspicion of nationalism among the other nationalities. It seems he had mix up in his different memoires the circumstances from the first and from the second congresses of IMRO, hold in 1894 and 1896 respectively, when a different statutes were adopted.

- Such Patriarchist Slavs who tended to identify themselves as Greeks or Serbs, were called then by the pro-Bulgarian IMRO-revolutionaries (sic) Grecomans and Serbomans, while the Vlachs with Bulgarian self-awareness were designated Bulgaromans.

Remove ads

External links

- The Regulations of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (scanned original) Archived 2023-08-17 at the Wayback Machine;

- The Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (in English) Archived 2023-05-01 at the Wayback Machine;

- The Statute of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (in Bulgarian) Archived 2023-03-21 at the Wayback Machine;

- The Regulations of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (in Bulgarian) Archived 2024-12-04 at the Wayback Machine;

- The Statute and the Regulations of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (in Macedonian);

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads