Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Book of Tobit

Deuterocanonical (apocryphal) book of Christian scripture From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Book of Tobit (/ˈtoʊbɪt/),[a][b] a work of Second Temple Jewish literature, is one of the deuterocanonical (or apocryphal) books of the Bible. It dates to the 3rd or early 2nd century BC. It emphasizes God’s testing of the faithful, his response to prayer, and his protection of the covenant people, the Israelites.[1] The narrative follows two Israelite families: the blind Tobit in Nineveh and Sarah, abandoned in Ecbatana.[2] Tobit’s son Tobias is sent to recover ten silver talents once deposited in Rhages in Media, and on his journey—guided by the angel Raphael—he meets Sarah.[2] Sarah is afflicted by the demon Asmodeus, who slays her prospective husbands, but with Raphael’s help the demon is exorcised and she marries Tobias.[1] They return together to Nineveh, where Tobit’s sight is miraculously restored.[2]

Since the 20th century, scholarly consensus has held that Tobit was originally composed in a Semitic language.[3] Five Aramaic and Hebrew fragments were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, dating to the 1st or 2nd century BC.[4] The book influenced the authors of the Testament of Job, the Testament of Solomon, and possibly (depending on dating) Sirach, Jubilees, and the Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children.[5] It was included in both the Jewish-originated Septuagint[6] and the Old Latin Bible, which preserves textual traditions of Hebrew or Jewish vorlage.[7][8] It is extant in major Christian codices such as Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, and Basiliano-Venetus. Multiple ancient recensions are preserved in Greek and Latin, along with translations into Arabic, Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Syriac.[9]

In the New Testament period, Tobit was cited or echoed by Jewish Christians including Matthew,[10][11][12][13] Luke,[14][15][16][17] John,[18][19][20][21] and the Didache.[22] Early patristic use appears in 2 Clement,[23] Polycarp,[24] and Origen, who after visiting 3rd-century Alexandria, Rome, Caesarea, and Athens, remarked that "the churches use Tobit".[25] Irenaeus further noted that the 2nd-century Gnostic Ophites included Tobit among the biblical prophets[26]

By contrast, explicit canonical rejection of Tobit by Rabbinic Judaism is recorded from the 2nd century onward. Rabbi Akiva declared "The books of Sirach and all other books written from then on do not defile the hands",[27] while a contemporary Talmudic baraita insisted that "our Rabbis taught" the present twenty-four book Masoretic canon.[28] Origen, though emphasizing Christian acceptance, acknowledged that "the Jews do not use [it]",[29] and Jerome likewise noted that the Bethlehem Jews had "excised" the book from their canon, relegating it to the non-canonical "agiografa", though still copying and reading it.[30] Fifteenth-century Hebrew and Aramaic manuscripts attest to its continued transmission, as does the medieval Midrash Tanhuma, which attributes a probable Tobit allusion to 11th-century Moshe ha-Darshan.[31]

The book is regarded as deuterocanonical by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, though it continues to be absent from the Jewish Masoretic Text. The Protestant tradition similarly deems it Apocrypha, useful for teaching and liturgy but not canonical; in the historic Protestant traditions, the Book of Tobit is located in the intertestamental section straddling the Old Testament and New Testament.[32][33][34][35] Most scholars see the book as a didactic folktale or novella which inserted storytelling elements into a historical context, rather than a strictly literal narrative.[36][37]

Remove ads

Structure and summary

Summarize

Perspective

The book has 14 chapters, forming three major narrative sections framed by a prologue and epilogue:[38]

- Prologue (1:1–2)

- Situation in Nineveh and Ecbatana (1:3–3:17)

- Tobias's journey (4:1–12:22)

- Tobit's song of praise and his death (13:1–14:2)

- Epilogue (14:3–15)

(Summarised from Benedikt Otzen, "Tobit and Judith").[39]

The prologue tells the reader that this is the story of Tobit of the tribe of Naphtali, deported from Tishbe in Galilee to Nineveh by the Assyrians. Tobit himself has always kept the laws of Moses, and brought offerings to the Temple in Jerusalem before the catastrophe of the Assyrian conquest. The narrative notes his marriage to Anna, and they have a son named Tobias.

Tobit, a pious man, buries dead Israelites, but one evening, while he sleeps, sparrows partially blind him by defecating in his eyes; he later becomes fully blind after physicians place ointment in his eyes.[40] He becomes dependent on his wife, but accuses her of stealing and prays for death. Meanwhile, his relative Sarah, living in far-off Ecbatana, also prays for death, for the demon Asmodeus has killed her suitors on their wedding-nights and she is accused of having caused their deaths.

God hears their prayers and dispatches the archangel Raphael to help them. Tobit sends Tobias to recover money from a relative, and Raphael, in human disguise, offers to accompany him (along with Tobias' dog). On the way they catch a fish in the Tigris, and Raphael tells Tobias that the burnt heart and liver can drive out demons and that the gall can cure blindness. They arrive in Ecbatana and meet Sarah; and as Raphael had predicted, the fish-offal drives out the demon.

Tobias and Sarah are married, Tobias grows wealthy, and they return to Nineveh (in Assyria) where Tobit and Anna await them. The gall cures Tobit's blindness, and Raphael departs after admonishing Tobit and Tobias to bless God and declare his deeds to the people (the Israelites), to pray and fast, and to give alms. Tobit praises God, who has punished his people with exile but who will show them mercy and rebuild the Temple if they turn to him.

In the epilogue Tobit tells Tobias that Nineveh will be destroyed as an example of wickedness; likewise Israel will be rendered desolate and the Temple will be destroyed, but Israel and the Temple will be restored; therefore Tobias should leave Nineveh, and he and his children should live in righteousness.

Remove ads

Significance

Tobit is a work with some historical references, combining prayers, ethical exhortation, humour and adventure with elements drawn from folklore, wisdom tale, travel story, romance and comedy.[36][41] It offered the diaspora (the Jews in exile) guidance on how to retain Jewish identity, and its message was that God tests his people's faith, hears their prayers, and redeems the covenant community (i.e., the Jews).[41]

Readings from the book are used in the Latin liturgical rites of the Catholic Church. Because of the book's praise for the purity of marriage, it is often read during weddings in many rites. Doctrinally, the book is cited for its teachings on the intercession of angels, filial piety, tithing and almsgiving, and reverence for the dead.[42][43] Tobit is also made reference to in chapter 5 of 1 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[44]

Remove ads

Composition and manuscripts

Tobit exists in two Greek versions, one (Sinaiticus) longer than the other (Vaticanus and Alexandrinus).[45] Aramaic and Hebrew fragments of Tobit (four Aramaic, one Hebrew – it is not clear which was the original language) found among the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran tend to align more closely with the longer or Sinaiticus version, which has formed the basis of most English translations in recent times.[45]

No scholarly consensus exists on the place of composition, but a Mesopotamian origin seems logical given that the story takes place in Assyria and Persia and it mentions the Persian demon "aeshma daeva", rendered "Asmodeus". However, the story contains significant errors in geographical detail (such as the distance from Ecbatana to Rhages and their topography), and arguments against and in favor of Judean or Egyptian composition also exist.[46] The story is set in the 8th century BC, but the book itself is thought to date from between 225 and 175 BC.[47]

The Vulgate places Tobit, Judith and Esther after the historical books (after Nehemiah). Some manuscripts of the Greek version place them after the wisdom writings.[48]

Canonical status

Summarize

Perspective

Those books found in the Septuagint but not the Masoretic Text are called the deuterocanon, meaning "second canon".[49] Catholic and Orthodox Christianity include it in the Biblical canon. As Protestants came to follow the Masoretic canon, they therefore did not include Tobit in their canon, but do recognise it in the category of deuterocanonical books called the apocrypha.[49]

The Book of Tobit is listed as a canonical book by the Council of Rome (AD 382),[50] the Council of Hippo (AD 393),[51] the Council of Carthage (397)[52] and (AD 419),[53] the Council of Florence (1442)[54] and finally the Council of Trent (1546),[55] and is part of the canon of the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Churches, and the Oriental Orthodox Churches. Catholics refer to it as deuterocanonical.[56]

Augustine[57] (c. AD 397) and Pope Innocent I[58] (AD 405) affirmed Tobit as part of the Old Testament Canon. Athanasius (AD 367) mentioned that certain other books, including the book of Tobit, while not being part of the Canon, "were appointed by the Fathers to be read".[59]

According to Rufinus of Aquileia (c. AD 400) the book of Tobit and other deuterocanonical books were not called Canonical but Ecclesiastical books.[60]

Protestant traditions place the book of Tobit in an intertestamental section called Apocrypha.[32] In Anabaptism, the book of Tobit is quoted liturgically during Amish weddings, with "the book of Tobit as the basis for the wedding sermon."[34] The Luther Bible holds Tobit as part of the "Apocrypha, that is, books which are not held equal to the sacred Scriptures, and nevertheless are useful to read".[35] Luther's personal view was that even if it were "all made up, then it is indeed a very beautiful, wholesome and useful fiction or drama by a gifted poet" and that "this book is useful and good for us Christians to read."[36] Article VI of the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England lists it as a book of the "Apocrypha".[61] The first Methodist liturgical book, The Sunday Service of the Methodists, employs verses from Tobit in the Eucharistic liturgy.[33] Scripture readings from the Apocrypha are included in the lectionaries of the Lutheran Churches and the Anglican Churches, among other denominations using the Revised Common Lectionary, though alternate Old Testament readings are provided.[62][63] Liturgically, the Catholic and Anglican churches may use a scripture reading from the Book of Tobit in services of Holy Matrimony.[64]

Tobit contains some interesting evidence of the early evolution of the canon, referring to two rather than three divisions, the Law of Moses (i.e. the torah) and the prophets.[65] For unknown reasons it is not included in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible, although four Aramaic and one Hebrew fragment were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, indicating an authoritative status among some sects.[66] Proposed explanations have included its age, literary quality, a supposed Samaritan origin, or an infringement of ritual law, in that it depicts the marriage contract between Tobias and his bride as written by her father rather than her groom.[67] Alternatively, allusions to fallen angels and its thematic connections with works such as 1 Enoch and Jubilees may have disqualified it from canonicity.[68] It is, however, found in the Greek text of the Septuagint, from which it was adopted into the Christian canon by the end of the 4th century.[67]

Remove ads

Influence

Tobit's place in the Christian canon allowed it to influence theology, art and culture in Europe.[69] It was often dealt with by the early Church fathers, and the motif of Tobias and the fish (the fish being a symbol of Christ) was extremely popular in both art and theology;[69] this is normally called Tobias and the Angel in art. Particularly noteworthy in this connection are the works of Rembrandt, who, despite belonging to the Dutch Reformed Church, was responsible for a series of paintings and drawings illustrating episodes from the book.[69]

Scholarship on folkloristics (for instance, Stith Thompson, Dov Noy, Heda Jason and Gédeon Huet) recognizes the Book of Tobit as containing an early incarnation of the story of The Grateful Dead, albeit with an angel as the hero's helper, instead of the spirit of a dead man.[70][71][72][73][74]

The story of Tobit inspired also the oratorio Il ritorno di Tobia (1775) by Joseph Haydn.

Remove ads

Image gallery

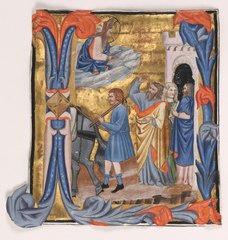

- Departure of Tobias guided by the archangel Raphael; cutting from an initial I from a gradual by the Master of Noah's Ark: Cleveland Museum of Art

- Tobias heals the blindness of his father Tobit, by Domingos Sequeira

- Anna and the Blind Tobit, Rembrandt and Dou (1630)

- Tobias and the Angel, Filippino Lippi, c. 1472–1482

- The wedding of Tobias and Sarah: Raphael binds the demon. Jan Steen, c. 1660

- Tobit and Anna, Abraham De Pape, c. 1658 National Gallery of London

- Tobit comforts Anna, stained glass roundel, southern Netherlands, c. 1500

- Tobit buries the dead, F. Bartolozzi after G.B. Castiglione, 1651.

- The Blindness of Tobit: A Sketch, William James Smith, After Rembrandt, ca. 1825.

Remove ads

See also

- Mary Untier of Knots (painting with Tobias and the Angel)

- Tobias and the Angel (Verrocchio)

- Philosopher in Meditation ("Tobit and Anna in an Interior" by Rembrandt)

Notes

- From the Ancient Greek: Τωβίθ Tōbith or Τωβίτ Tōbit (Τωβείθ and Τωβείτ spellings are also attested), itself derived from Hebrew: טובי Tovi meaning "my good"; Book of Tobias in the Vulgate from the Greek Τωβίας Tōbias, which in turn comes from the Hebrew טוביה Tovyah "Yah is good"

- Also known as the Book of Tobias.

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads