Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Buddhism in Indonesia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Buddhism has a long history in Indonesia, and it is one of the six recognized religions in the country, along with Islam, Christianity (Protestantism and Catholicism), Hinduism and Confucianism. According to 2023 estimates roughly 0.71% of the total citizens of Indonesia were Buddhists, numbering around 2 million. Most Buddhists are concentrated in Jakarta, Riau, Riau Islands, Bangka Belitung, North Sumatra, and West Kalimantan. These totals, however, are probably inflated, as practitioners of Taoism, Tridharma, Yiguandao, and other Chinese folk religions, which are not considered official religions of Indonesia, likely declared themselves as Buddhists on the most recent census.[4] Today, the majority of Buddhists in Indonesia are Chinese Indonesians, but communities of native Buddhists (such as Javanese, Tenggerese, Sasak, Balinese, Dayak, Alifuru, Batak, and Karo) also exist.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

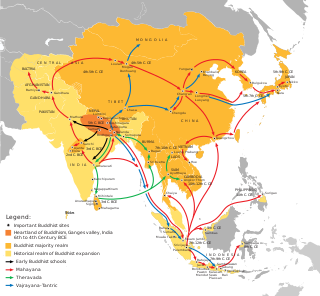

Antiquity

Buddhism, especially Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism, is the second oldest outside religion in Indonesia after Hinduism, which arrived from India around the second century.[4] The history of Buddhism in Indonesia is closely related to the history of Hinduism, as a number of empires influenced by Indian culture were established around the same period. The arrival of Buddhism in the Indonesian archipelago began with trading activity, from the early 1st century, by way of the maritime Silk Road between Indonesia and India.[6] The oldest Buddhist archaeological site in Indonesia is arguably the Batujaya stupas complex in Karawang, West Java. The oldest relic in Batujaya was estimated to originate from the 2nd century, while the latest dated from the 12th century. Subsequently, significant numbers of Buddhist sites were found in Jambi, Palembang, and Riau provinces in Sumatra, as well as in Central and East Java. The Indonesian archipelago has, over the centuries, witnessed the rise and fall of powerful Buddhist empires, such as the Sailendra dynasty and the Mataram and Srivijaya empires.

According to some Chinese sources, the Chinese Buddhist monk I-tsing, while on his pilgrim journey to India, witnessed the powerful maritime empire of Srivijaya based on Sumatra in the 7th century. The empire served as a Buddhist learning center in the region. A notable Srivijayan revered Buddhist scholar is Dharmakīrtiśrī, a Srivijayan prince of the Sailendra dynasty, born around the turn of the 7th century in Sumatra.[7] He became a revered scholar-monk in Srivijaya and moved to India to become a teacher at the famed Nalanda University, as well as a poet. He built on and reinterpreted the work of Dignaga, the pioneer of Buddhist logic, and was very influential among Brahman logicians as well as Buddhists. His theories became normative in Tibet and are studied to this day as a part of the basic monastic curriculum. Other Buddhist monks who visited Indonesia were Atisha, Dharmapala, a professor of Nalanda, and the South Indian Buddhist Vajrabodhi. Srivijaya was the largest Buddhist empire ever formed in Indonesian history. Indian empires such as the Pala Empire helped fund Buddhism in Indonesia; specifically funding a monastery for Sumatran monks.[8]

A number of Buddhist sites and artifacts related to Indonesia's historical heritage can be found in Indonesia, including the 8th century Borobudur mandala cmonument and Sewu temple in Central Java, Batujaya in West Java, Muaro Jambi, Muara Takus and Bahal temple in Sumatra, and numerous statues or inscriptions from the earlier history of Indonesian Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms. During the eras of the Kediri, Singhasari and Majapahit empires, Buddhism — identified as Dharma ri Kasogatan — was acknowledged as one of the kingdom's official religions along with Hinduism. Although some of the kings may have favored Hinduism, harmony, religious tolerance, and even syncretism were promoted as a manifestation of the national motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, which was coined from the Kakawin Sutasoma, written by Mpu Tantular to promote tolerance and coexistence between Hindus (Shivaites) and Buddhists.[9] The classical era of ancient Java has also produced some of the most exquisite examples of Buddhist art; such as the statue of Prajnaparamita and the statue of Buddha Vairochana and Boddhisttva Padmapani and Vajrapani located in the Mendut temple.

Decline and revival

Coming of Islam

In the 13th century, Islam entered the archipelago, and began gaining a foothold in coastal port towns. The fall of the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit empire in the late 15th or early 16th century marked the end of Dharmic civilization in Indonesia. By the end of the 16th century, Islam had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra. For 450 years after that, there was no significant Buddhist practice in Indonesia. Many Buddhist sites, stupas, temples, and manuscripts were lost or forgotten as the region became predominantly Muslim. During this era of decline, few people practiced Buddhism; most of them were Chinese immigrants who settled in Indonesia when migration accelerated in the 17th century. Many kelenteng (Chinese temples) in Indonesia are in fact a tridharma temple that houses three faiths, namely Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.

First missionary effort

In 1934, Narada Thera, a Theravada Buddhist missionary monk from Sri Lanka, visited the Dutch East Indies for the first time as part of his journey to spread the Dhamma in Southeast Asia.[10] This opportunity was seized by local Buddhists to revive Buddhism in Indonesia. A Bodhi tree planting ceremony was held on the southeastern side of Borobudur on March 10, 1934, under the blessing of Narada Thera, and some lay followers were ordained as monks.[4]

Modern Indonesia

State-recognized religions

On January 27, 1965, under the Soekarno administration through Presidential Decree No. 1/PNPS/1965, the legal foundation for the "five religions embraced by the population of Indonesia" concept was established. This document was the first to list the religions within its official elucidation, namely Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism and Buddhism.

The three teachings

Although the belief system is called "Buddhism" and the followers identify themselves as "Buddhists," many of them were actually practicing Tridharma ("the three teachings"), a Chinese syncretised form of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism.[10]

Later, it was the figures from Tridharma who then separated themselves and formed various modern Buddhist organizations that still survive, such as the Indonesian Buddhayana Council (along with Sangha Agung Indonesia) and the Sangha Theravada Indonesia.

National Vesak celebration

The first modern Vesak (Waisak) celebration after Indonesia's independence was held in 1953 at Borobudur Temple, marking a pivotal moment in the national revival of this tradition. Looking back, however, the celebration of Vesak at Borobudur and Mendut temples had actually begun as early as 1929, initiated by the Theosophical Society of the Dutch East Indies. This nascent tradition then came to a complete halt during the Indonesian National Revolution from 1945 to 1949, before finally being revived in 1953 and later officially established as a national holiday in 1983.[11]

Inter-sectarian Buddhayana

In 1955, Ashin Jinarakkhita formed the first Indonesian Buddhist lay organisation, Persaudaraan Upasaka Upasika Indonesia (PUUI). In 1957, the PUUI was integrated into the Indonesian Buddhist Association (Perhimpunan Buddhis Indonesia, Perbudhi), in which both Theravada and Mahayana priesthood were united.[12][13] Nowadays, the PUUI is called Majelis Buddhayana Indonesia (MBI).[14]

In 1960, Jinarakkhita established the Sangha Suci Indonesia, as a monastic organisation. In 1963, the name was changed to Maha Sangha of Indonesia, and in 1974 until the present day, the name was changed into Sangha Agung Indonesia. It is a community of inter-school monastics from the Theravada, Mahayana and Tantrayana schools.[15][16]

Belief in one supreme God

Following the downfall of President Sukarno in the mid-1960s, Pancasila was reasserted as the official Indonesian policy on religion to only recognise monotheism.[17] In 1965, after a coup-attempt, Buddhist organisations had to comply with the first principle of the Indonesian state ideology, Pancasila, the belief in one supreme God.[16] All organisations that doubted or denied the existence of God were outlawed.[18] This posed a problem for Indonesian Buddhism, which was solved by Jinarakkhita by presenting Nibbāna (Nirvana) as the Theravada "God", and Adi-Buddha, the primaeval Buddha of the region's previous Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism, as the Mahayana "God",[18] although this interpretation of the Buddha is controversial and not widely accepted by the Theravada school of Buddhism.[19] According to Jinarakkhita, the concept of Adi Buddha was found in the tenth-century Javanese Buddhist text Sang Hyang Kamahayanikan.[16]

Restriction of Chinese religions

During the New Order era (1966–1998) under President Suharto, the "state-recognized religions" policy was implemented with great rigidity. Through Presidential Instruction No. 14 of 1967, the public practice of Chinese folk religions, beliefs, and customs, including Confucianism, and Indonesian folk religions were severely restricted and suppressed. As a consequence, only five religions were de facto recognized and facilitated by the state, which strongly reinforced the public understanding of there being "five official religions." Many formal Chinese traditional beliefs such as Confucianism and Taoism were also incorporated into the Buddhist practices of Chinese Indonesian Buddhists who were mostly of the Mahayana school, labelling the folk religions as a part of "Buddhism".[20][21] During this time, many Chinese temples changed their names from Chinese names to Pali or Sanskrit.[10]

Chinese Indonesians, in particular, had increasingly embraced Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism). Catholic growth prior to World War II was slow, but subsequently saw some success, most notably after 1965 and the New Order, where all Indonesians were required to proclaim an approved religion. For example, between 1950 and 2000, the Catholic population grew from 1.1% to 8.7% in the Archdiocese of Pontianak, while in the Diocese of Sintang, it grew from 1.7% to 20.1%.[citation needed] Catholicism and other minority religions have experienced enormous growth especially in areas inhabited by large numbers of Chinese Indonesians (who were practicing Chinese folk religions) and ethnic Javanese (who were practicing Indonesian folk religions or aliran kepercayaan). In 2000, there were 301,084 Catholics in Jakarta, compared to only 26,955 in 1960. This means the Catholic population increased elevenfold while in the same period the population of Jakarta merely tripled, from 2,800,000 to 8,347,000.[22] In the early 2000s, some reports also show that many Chinese Indonesians converted to Christianity.[23][24] Demographer Aris Ananta reported in 2008 that "anecdotal evidence suggests that more Buddhist Chinese have become Christians as they increased their standards of education".[23]

Strengthening Theravada roots

Eventually, the Theravada school of Buddhism also began to strengthen its foundations in Indonesia. With the help of monks from the Thai Dhammayuttika Nikāya order, Saṅgha Theravāda Indonesia (Indonesian Theravāda Saṅgha), the first monastic organization of Theravada Buddhism in Indonesia, was formed on October 23, 1976, at the Mahā Dhammaloka Vihāra (now Tanah Putih Vihāra), Semarang, Central Java.[25][26] This organization was initiated by monks who did not agree with the inter-sectarian views of the Indonesian Buddhayana Council. In 1979, the first Buddhist college in Indonesia, Nalanda Institute, was established with the ideal of fulfilling the need for Buddhist teachers to educate Buddhist students.[27][28][29]

Recognition of Confucianism

Following the fall of Suharto in 1998, Abdurrahman Wahid was elected as the country's fourth president. He rescinded the 1967 Presidential Instruction and the 1978 Home Affairs Ministry directive, and Confucianism once again became officially recognised as a religion in Indonesia. Chinese culture and activities were again permitted.[30] This impacted the Buddhist population numbers because Confucianists began to update their national indentity cards (KTP), although many Chinese Indonesians still have not updated it because they could not find a clear dividing line between Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion, and formal Buddhism.

Theravadization of Indonesian Buddhism

In 1981, Berchert argues that the introduction of Theravada Buddhism in Indonesia was largely the result of efforts by Ashin Jinarakkhita, who had been ordained as a monk in Burma. Bechert identifies several important developments during the 1950s that facilitated this revival. These include the establishment of various Buddhist organizations beginning in 1952 and, most significantly, the 1958 visit of Bhikkhu Narada to Java, which laid the foundation for a Buddhist center in Semarang. Bechert's analysis also notes a subsequent trend in the 1970s, where some Chinese temples were gradually converted into Theravada temples.[31][10]

A 2024 study by Buaban, Makin, and Sutrisno analyzes the "Theravadization" of the Buddhayana movement in Indonesia, arguing that while the movement claims to be non-sectarian, its public doctrines and rituals became predominantly Theravada in character. This shift was attributed to two main factors: the transnational discourse of "modern Buddhism," which emphasized Theravada's "rational" teachings and Vipassana meditation as scientific, and Indonesian political pressures, specifically the New Order's assimilation policy that marginalized Mahayana Buddhism due to its strong association with Chinese culture (see Han Buddhism). As a result, Mahayana practices were largely confined to private spaces like homes and kelenteng (Chinese temples), while Theravada was presented in the public sphere to align with the state's needs, a phenomenon visibly demonstrated in the Theravada-dominated national Vesak celebrations.[32]

In 2002, Kertarajasa Buddhist College (STAB Kertarajasa), a Theravada Buddhist private university, was established to accommodate the need for Buddhist religious teachers and preachers.[33][34][29] Later, the Pa-Auk Forest Monastery tradition, along with other Burmese traditions, also planted their Theravadin roots in Indonesia by establishing various branches throughout the country.[35][36] In 2015, another separate Theravadin organization, Saṅgha Bhikkhuṇī Theravāda Indonesia, held the first Theravada ordination of bhikkhunis in Indonesia at Wisma Kusalayani in Lembang, Bandung, West Java,[37] although the validity of this ordination remains controversial among the conservatives (see Bhikkhunī#Re-establishing bhikkhunī ordination),[38] and is not officially recognized by the Saṅgha Theravāda Indonesia.[39]

Diverse Buddhist schools

Over time, as the discrimination of the New Order subsided, other Buddhist schools also began to build their organizations in Indonesia. A 2022 study by Abdul Syukur analyzes the theological debates among Buddhist schools in Indonesia, which arose from the constitutional requirement for each recognized religion to have a concept of one God. The Buddhayana movement successfully addressed this by formulating "Sang Hyang Adi Buddha" as the name of God, based on the Javanese text Sang Hyang Kamahayanikan, a pragmatic move that secured official state recognition for Buddhism. However, this concept was rejected by the Theravada school, which argued that the source text was not from the Pali Canon and instead proposed its own concept of an unnamed, impersonal absolute found in the Udāna scripture (Tatiyanibbānapaṭisaṁyutta Sutta, Ud 8.3), that is a reference to Nibbāna (Nirvana). The Mahayana scool bases its concept of the Godhead on the philosophical principle of the dharmakaya (the eternal, absolute body of the Buddha), while the Nichiren Shoshu Indonesia (NSI) sect identifies God with the Natural Law, embodied in the mantra Nammyohorengekyo, and considers its founder, Nichiren, to be a Buddha. These conflicting doctrines, stemming from each sect's reliance on different Buddhist canons, have resulted in significant disunity and potential for conflict within the Indonesian Buddhist community (see #Inter-school blasphemy).[19]

Representatives

Today, in reference to the principle of Pancasila, a Buddhist monk or pandita representing the Buddhist sangha or parisā (assembly), along with a priest, Brahmin, clergy or representative of other recognized religions, participate in nearly all state-sponsored ceremonies to lead prayers according to their respective faiths.[40]

Once a year, thousands of Buddhists from Indonesia and neighboring countries flock to Borobudur to commemorate the national Waisak Day.[41]

Remove ads

Distribution

Summarize

Perspective

According to the 2018 civil registration, there were 2,062,150 Buddhists in Indonesia.[42] The percentage of Buddhists in Indonesia increased from 0.7% in 2010 to 0.77% in 2018.

Buddhism, whether the three main traditional schools (Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana) or the syncretised versions, is mainly followed by the Chinese community and some indigenous groups of Indonesia, such as the Javanese, Tenggerese, Sasak, Balinese, Dayak, Alifuru, Batak, and Karo.

Organizations

The organizational structure of Buddhism in modern Indonesia is largely characterized by temple affiliations, which can be broadly categorized under some religious councils:

- Theravada school:

- Dhammayuttika Nikaya order and its successors:

- Keluarga Buddhis Theravada Indonesia (KBTI)

- Sangha Theravada Indonesia (STI), for the monks

- Atthasilani Theravada Indonesia (Astinda), for the nuns

- Majelis Agama Buddha Theravada Indonesia (Magabudhi), for the lay followers and panditas

- Wanita Theravada Indonesia (Wandani), specifically for women

- Pemuda Theravada Indonesia (Patria), for the youth

- Sangha Theravada Dhammayut Indonesia (STDI)

- Keluarga Buddhis Theravada Indonesia (KBTI)

- Maha Nikaya order:

- Sangha Dhamma Duta Indonesia (SDDI)

- Majelis Agama Buddha Mahanikaya Indonesia (MBMI)

- Shwegyin Nikaya order:

- Yayasan Satipatthana Indonesia (Yasati)

- Yayasan Dhammavihari (DBS)

- Yayasan Dhammika Kalyanasahaya (DKS)

- Yayasan Kammatthanasamuttapaka Nikaya (KSN)

- Pa-Auk Tawya Vipassana Dhura Hermitage Indonesia (PATVDH Indonesia), part of the Pa-Auk Society led by Bhaddanta Āciṇṇa (Pa-Auk Sayadaw)

- Order-less:

- Sangha Bhikkhuni Theravada Indonesia

- Majelis Umat Buddha Theravada Indonesia (Majubuthi)

- Dhammayuttika Nikaya order and its successors:

- Mahayana schools:

- Majelis Agama Buddha Mahayana (Majubumi)

- Sangha Mahayana Indonesia (SMI)

- Majelis Mahayana Indonesia (Mahasi)

- Majelis Mahayana Buddhis Indonesia (Mahabudhi)

- Parisadha Buddha Dharma Niciren Syosyu Indonesia (NSI)

- Majelis Nichiren Shoshu Buddha Dharma Indonesia (MNSBDI)

- Perhimpunan Buddhis Nichiren Shu Indonesia (PBNSHI)

- Soka Gakkai Indonesia, part of the Soka Gakkai International

- Majelis Agama Buddha Mahayana Tanah Suci (Majabumi TS)

- Mahayana-based organizations, such as Yayasan Buddha Tzu Chi Indonesia, Yayasan Buddha Fo Guang Shan Indonesia, and others

- Vajrayana schools, interschools, syncretised schools, and others:

- Keluarga Buddhayana Indonesia (KBI), an interschool organization that encompasses all three main Buddhist schools at once:

- Sangha Agung Indonesia (SAGIN), for the monks, divided based on the school affiliation

- Sangha Vajrayana Indonesia, a sub-division specifically for Vajrayana monks

- Majelis Buddhayana Indonesia (MBI), for the lay followers

- Sekretariat Bersama Persaudaraan Muda-Mudi Vihara-Vihara Buddhayana Indonesia (Sekber PMVBI), for the youth

- Sangha Agung Indonesia (SAGIN), for the monks, divided based on the school affiliation

- Tridharma (syncretism of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism):

- Majelis Agama Buddha Tridharma Indonesia (Magabutri), for the general lay followers

- Majelis Rohaniawan Tridharma Indonesia (Matrisia), for the panditas

- Pemuda Tridharma Indonesia (Petrisia), for the youth

- Wanita Agama Buddha Tridharma Indonesia (Wagabutri), specifically for women

- Majelis Umat Nyingma Indonesia (MUNI)

- Majelis Palpung Indonesia

- Sangha Kadam Choeling Indonesia

- Majelis Zhenfo Zong Kasogatan (ZFZ Kasogatan)

- Majelis Agama Buddha Tantrayana Indonesia (Majabudti)

- Majelis Agama Buddha Tantrayana Satya Buddha Indonesia (Madha Tantri)

- Majelis Agama Buddha I Kuan Tao Indonesia (Mabikti)

- Majelis Pandita Buddha Maitreya Indonesia (Mapanbumi)

- Majelis Agama Buddha Guang Ji Indonesia (MABGI)

- Vajrayana-based organizations, such as Yayasan Arya Taray Nusantara and others

- Keluarga Buddhayana Indonesia (KBI), an interschool organization that encompasses all three main Buddhist schools at once:

Indonesia's most notable Buddhist organization is Perwakilan Umat Buddha Indonesia (Walubi) which serves as the vehicle of all Buddhist schools in Indonesia.

Indigenous groups

Pockets of Javanese Buddhists exist mainly in villages and cities in Central and East Java. The regencies of Temanggung, Blitar and Jepara count about 30,000 Buddhists, mostly of Javanese ethnicity. For example, native Javanese Buddhists population formed as the majority in mountainous villages of Kaloran subdistrict in Temanggung, Central Java.[43] The Tenggerese people, a Javanese sub-ethnic group, maintain that they practice their faith in Buddhism specifically to uphold the legacy of their ancestors,[44] although they mainly practice Theravada Buddhism in the present day,[45] rather than the historical Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism.

A small minority of Sasaks called the "Bodha" are mainly found in the village of Bentek and on the slopes of Gunung Rinjani, Lombok. They had managed to avoid any Islamic influence and worship deities like Dewi Sri with Esoteric Buddhist and Hindu influences in their rituals due to their secluded geographical location. This group of Sasak, due in part to the name of their tribe, are recognized as Buddhists by the Indonesian government. At present, there are more than 10,000 Buddhists in their community and belonging to the Theravada school.[46]

In the remote interior of Seram Island in Maluku, the Yamatitam people, a subgroup of the indigenous Alifuru tribe, represent another unique Buddhist community. Traditionally living a simple and nomadic life in the mountains, their community had limited contact with the outside world and did not speak the national language. Their journey into Theravada Buddhism began after making contact with a lay follower, who had previously employed them and served as a trade associate, and eventually monks of the Sangha Theravada Indonesia, who started providing them with spiritual guidance and support from 2014. This relationship has not only introduced them to Buddhist teachings but also assisted in their social and educational development, helping to connect their secluded community with the wider Indonesian society, notably through events like joint Vesak celebration and mass wedding ceremonies.[47]

Other missionary efforts were also initiated among the Balinese,[48][49] Dayak,[50][51] Batak, Karo[52][53] and various other ethnic groups.[54] As a result, the Buddhist distribution in Indonesia consists of various ethnicities, not limited to Chinese Indonesians. There are also some Tamil[55][56] and Thai[57][58] Theravada Buddhists who reside in Indonesia.

By provinces

Most Chinese Indonesians reside in urban areas, thus Indonesian Buddhist also mostly live in urban areas. Top ten Indonesian provinces with significant Buddhist populations are Jakarta, North Sumatra, West Kalimantan, Banten, Riau, Riau Islands, West Java, East Java, South Sumatra, and Central Java.[3]

Remove ads

Literature and arts

Summarize

Perspective

Buddhist literature

Antique literature

The oldest extant esoteric Buddhist Mantranaya (largely a synonym of Mantrayana, Vajrayana and Buddhist Tantra) literature in Old Javanese, a language significantly influenced by Sanskrit, is enshrined in the Sang Kyang Kamahayanan Mantranaya.[59]

The Lalitavistara Sutra was known to the Mantranaya stonemasons of Borobudur, refer: The birth of Buddha (Lalitavistara). 'Mantranaya' is not a corruption or misspelling of 'mantrayana' even though it is largely synonymous. Mantranaya is the term for the esoteric tradition on mantra, a particular lineage of Vajrayana and Tantra, in Indonesia. The clearly Sanskrit sounding 'Mantranaya' is evident in Old Javanese tantric literature, particularly as documented in the oldest esoteric Buddhist tantric text in Old Javanese, the Sang Kyang Kamahayanan Mantranaya refer Kazuko Ishii (1992).[60]

The canons

In modern Indonesia, the Buddhist literature in use is derived from ancient Buddhist canons translated into the Indonesian language. The Theravada school emphasizes the utilization of the Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) in the Pali language along with its commentaries and translations; the Mahayana school mostly draws from the Chinese Buddhist canon in Classical Chinese and its translations; and the Vajrayana school relies on the Tibetan Buddhist canon (Kangyur and Tengyur), depending on the lineage.

However, due to the large volume of the canons, each school more frequently uses the paritta or dharani books for daily to weekly chanting,[61] although the canons remain the primary basis for sermons and in-depth study (pariyatti).[62]

Buddhist arts

Antique arts

Like the rest of Southeast Asia, Indonesia seems to have been most strongly influenced by India from the 1st century CE. The islands of Sumatra and Java in western Indonesia were the seat of the empire of Sri Vijaya (8th–13th century), which came to dominate most of the area around the Southeast Asian peninsula through maritime power. The Sri Vijayan Empire had adopted Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, under a line of rulers named the Shailendra. The Shailendras was the ardent temple builder and the devoted patron of Buddhism in Java.[63] Sri Vijaya spread Mahayana Buddhist art during its expansion into the Southeast Asian peninsula. Numerous statues of Mahayana Bodhisattvas from this period are characterized by a very strong refinement and technical sophistication, and are found throughout the region. One of the earliest Buddhist inscription in Java, the Kalasan inscription dated 778, mentioned about the construction of a temple for the goddess Tara.[63]

Extremely rich and refined architectural remains are found in Java and Sumatra. The most magnificent is the temple of Borobudur (the largest Buddhist structure in the world, built around 780–850 AD), built by Shailendras.[63] This temple is modelled after the Buddhist concept of universe, the Mandala which counts 505 images of the seated Buddha and unique bell-shaped stupa that contains the statue of Buddha. Borobudur is adorned with long series of bas-reliefs narrated the holy Buddhist scriptures.[64] The oldest Buddhist structure in Indonesia probably is the Batujaya stupas at Karawang, West Java, dated from around the 4th century. This temple is some plastered brick stupas. However, Buddhist art in Indonesia reach the golden era during the Shailendra dynasty rule in Java. The bas-reliefs and statues of Boddhisatva, Tara, and Kinnara found in Kalasan, Sewu, Sari, and Plaosan temple is very graceful with serene expression, While Mendut temple near Borobudur, houses the giant statue of Vairocana, Avalokitesvara, and Vajrapani.

In Sumatra Sri Vijaya probably built the temple of Muara Takus, and Muaro Jambi. The most beautiful example of classical Javanese Buddhist art is the serene and delicate statue of Prajnaparamita of Java (the collection of National Museum Jakarta) the goddess of transcendental wisdom from Singhasari kingdom.[65] The Indonesian Buddhist Empire of Sri Vijaya declined due to conflicts with the Chola rulers of India, then followed by Majapahit empire.

- The Buddha in Borobudur

- The statue of Prajñāpāramitā from Singhasari, East Java, on a lotus throne

Contemporary Buddhist music

In contemporary Indonesia, some Buddhist groups are developing new worship styles by adapting popular music to attract younger followers. A notable example is True Direction, a Buddhist rock band and music organization from Jakarta founded by Irvyn Wongso in 2015. The group creates what the author terms "Buddhist rock", rock and popular music with lyrics centered on Buddhist teachings, a style that resembles contemporary Christian music. Rather than replacing traditional Buddhist devotional practices, True Direction aims to complement them, using music as an evangelical tool to engage youth who may not be interested in visiting temples. The organization functions as a music school, training musicians and producing modern Buddhist songs which they promote through albums like Dhamma is My Way and social media. While this innovative approach has been successful in reaching younger audiences in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, it has also drawn criticism from some conservative Indonesian Buddhists who are concerned about the "Christianized" style and the potential for it to corrupt young people's understanding of the faith. Despite this, the movement signifies a "selective adaptation" of modern culture to repackage and propagate Buddhist doctrine in the world's largest Muslim nation.[66] Other notable Buddhist contemporary worship bands are Buddhist Worship, Sadhu United, and Kalyana Project.

Remove ads

Festivals

Summarize

Perspective

Vesak

The most important Buddhist religious event in Indonesia is Vesak (Indonesian: Waisak). Once a year, during the full moon in May or June, Buddhists in Indonesia observe Vesak day commemorating the birth, death, and the time when Siddhārtha Gautama attained the highest wisdom and became a Buddha. Vesak is an official national holiday in Indonesia[67] and the ceremony is centered at the three Buddhist temples by walking from Mendut to Pawon and ending at Borobudur.[68] Vesak also is often celebrated in Sewu temple and numerous regional temples in Indonesia.

Asalha

In Indonesia, the annual Asalha Puja (Indonesian: Asalha) celebration is also centered at Borobudur Temple, where it incorporates the Indonesia Tipiṭaka Chanting (ITC). Initiated in 2015, this event usually spans three days during which devotees recite passages from the Pali Canon in the Pali language and undertake the Eight Precepts. The celebration culminates in a grand puja procession where thousands of participants mindfully walk from Mendut to Borobudur, commemorating the Buddha's first sermon.[69][70]

Remove ads

Conflicts

Summarize

Perspective

Discrimination and protests

The Chinese Indonesian community in Tanjung Balai municipality in North Sumatra has protested against the administration's plan to dismantle a statue of Buddha on top of the Tri Ratna Temple.[71][72]

On July 29, 2016, several Buddhist temples were plundered and burnt down in Tanjung Balai of North Sumatra. The incident followed a protest triggered by a resident of Chinese descent, Meliana, who complained about the loud volume of the azan (call to prayer) from a nearby mosque. Although Meliana had apologized, a mob of around 1,000 people attacked Buddhist temples and Chinese-owned shops and homes. According to police, the violence was incited by rumors spread through social media. Despite attempts by local figures to mediate and calls for calm, the mob proceeded with the destruction. At least eight vihāras and pagodas were damaged or set on fire. Authorities reported deploying hundreds of police and military personnel to control the situation and prevent further violence. Several suspects were later arrested in connection with the attacks. The incident drew condemnation from various religious and community leaders, highlighting concerns about religious intolerance and the spread of misinformation in Indonesia.[73]

On 26 November 2016, a homemade bomb was discovered in front of Vihara Buddha Tirta, a Buddhist temple in Lhok Seumawe of Aceh.[74]

Inter-school blasphemy

On June 2, 2020, Leo Pratama Limas, a Chinese-Indonesian Theravada Buddhist extremist, was reported by several Buddhist activists for allegedly spreading hate speech through electronic media. He was subsequently arrested, and his trial began on September 24, 2020, at the North Jakarta District Court. Leo was charged under Article 28, paragraph 2 of the Electronic Information and Transactions Law (ITE Law). The charges stemmed from his YouTube sermons, which were deemed insulting to important figures and symbols in Mahayana Buddhism. The controversial statements included referring to Guanyin as a "water demon" (setan air) and a "crybaby demon" (setan cengeng), and the main deity of Yiguandao (known as "Maitreya Buddhism" in Indonesia) as a "female God" (tuhan betina). In addition to verbal insults, Leo was also accused of desecrating Mahayana sutras by stepping on, burning, and immersing them in water. He also allegedly insulted Ashin Jinarakkhita, the monk who found the inter-sectarian Buddhayana, by calling him a "stupid ascetic" (pertapa dungu). In his defense, Leo claimed his actions were not blasphemy but an attempt to enlighten Buddhists whom he considered to be "lost." According to him, the scriptures he damaged were heretical, and his statements were the truth. The prosecution confirmed that Leo was mentally sound at the time of his actions.[75][76]

Remove ads

See also

- Abangan

- Waisak Day

- Ashin Jinarakkhita

- Narada Maha Thera

- Parwati Soepangat

- Metta Sutta

- Mangala Sutta

- Lumbini Natural Park

- Vihara Buddhagaya Watugong

- Borobodur

- Dharmakīrtiśrī

- Lalitavistara Sūtra

- Candi of Indonesia

- Sanghyang Adi Buddha

- Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism

- A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea

- Buddhism in Malaysia

- Buddhism in Southeast Asia

Remove ads

Notes

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads