Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Celtiberian language

Extinct Celtic language of Iberia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar, and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in the Latin alphabet. The longest extant Celtiberian inscriptions are those on the Botorrita plaques, three bronze plaques from Botorrita near Zaragoza dating to the early 1st century BC, labeled Botorrita I, III, and IV (Botorrita II is in Latin). Shorter and more fragmentary is the Novallas bronze tablet.[2]

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

According to the P/Q Celtic hypothesis, and like its Iberian relative Gallaecian, Celtiberian is classified as a Q Celtic language, putting it in the same category as Goidelic and not P-Celtic like Gaulish or Brittonic.[3]

According to the Insular/Continental Celtic hypothesis, Celtiberian and Gaulish are grouped together as Continental Celtic languages, but this grouping is paraphyletic: no evidence suggests that the two shared any common innovation separately from Insular Celtic. According to Ranko Matasovic in the introduction to his 2009 Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic: "Celtiberian...is almost certainly an independent branch on the Celtic genealogical tree, one that became separated from the others very early."[4]

Celtiberian has a fully inflected relative pronoun ios (as does, for instance, Ancient Greek), an ancient feature that was not preserved by the other Celtic languages, and the particles -kue 'and' < *kʷe (cf. Latin -que, Attic Greek τε te), nekue 'nor' < *ne-kʷe (cf. Latin neque), ekue 'also, as well' < *h₂et(i)-kʷe (cf. Lat. atque, Gaulish ate, OIr. aith 'again'), and ve "or" (cf. Latin enclitic -ve, Attic Greek ἤ ē < Proto-Greek *ē-we). As in Welsh, there is an s-subjunctive; e.g., gabiseti "he shall take" (Old Irish gabid), robiseti, auseti. Compare Umbrian ferest "he/she/it shall make" or Ancient Greek δείξῃ deiksēi (aorist subj.) / δείξει deiksei (future ind.) "(that) he/she/it shall show".

Remove ads

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Celtiberian shows the characteristic sound changes of Celtic languages, such as:[5]

PIE consonants

- PIE *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ > b, d, g: Loss of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) voiced aspiration.

- Celtib. and Gaulish [Gaul.] placename element -brigā 'hill, town, akro-polis' < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-eh₂.

- nebintor 'they are watered' < *nebʰ-i-nt-or.

- dinbituz 'he must build' < *dʰingʰ-bī-tōd; ambi-dingounei 'to build around > to enclose' < *h₂m̥bi-dʰingʰ-o-mn-ei; cf. Latin [Lat.] fingō 'to build, shape' < *dʰingʰ-o, Old Irish (OIr.) cunutgim 'erect, build up' < *kom-ups-dʰingʰ-o; ambi-diseti '(that someone) builds around > enclose' < *h₂m̥bi-dʰingʰ-s-e-ti.

- gortika 'mandatory, required' < *gʰor-ti-ka; cf. Lat. ex-horto 'exhort' < *ex-gʰor-to). However, since the meaning in Celtiberian cannot be determined with certainty, this root may be related to OIr. gort "field" (< PIE *ghо̄rdh-s, gen. *ghrdh-os ‘enclosure, garden, pen') and its many IE cognates.[6]

- duatir 'daughter' < *dʰugh₂tēr, duateros 'grandson, son of the daughter''; cf. Common Celtic (ComCelt.) *duxtir.

- bezom 'mine' < *bʰedʰ-yo 'that which is pierced'.

- PIE *kʷ: Celtiberian preserved the PIE voiceless labiovelar kʷ (hence Q-Celtic), a development also observed in Archaic Irish and Latin. On the contrary, Brythonic and Gaulish (P-Celtic) changed kʷ to p, a change also seen in some dialects of Ancient Greek and some Italic branches like P-Italic. E.g., -kue 'and' < *kʷe, Lat. -que, Osco-Umbrian -pe 'and', neip 'and not, neither' < *ne-kʷe.

- PIE *ḱw > ku: ekuo horse (in the name Ekualakos) < *h₁eḱw-ālo; cf. Middle Welsh (MW) ebawl foal' < *epālo, Lat. equus 'horse', OIr. ech 'horse' < *eko´- < *h₁eḱwo-, Old Breton (OBret) eb < *epo- < *h₁eḱwo-.

- kū 'dog' < *kuu < *kwōn, in Virokū, 'hound-man, male hound/wolf, werewolf'; cf. OIr. Ferchú, Old Welsh (OW) Gurcí < *Virokū 'idem'.[7]

- PIE *gʷ > b: bindis 'legal agent' < *gʷiHm-diks; cf. Lat. vindex 'defender'.[8]

- bovitos 'cow passage' < *gʷow-(e)ito; cf. OIr. bòthar 'cow passage' < *gʷow-(e)itro)[9], boustom 'cowshed' < *gʷow-sto.

- PIE *gʷʰ > gu: guezonto < *gʷʰedʰ-y-ont 'imploring, pleading'; cf. ComCelt. *guedyo 'ask, plead, pray', OIr. guidid, W. gweddi.

- PIE *p > *φ > ∅: loss of PIE *p, e.g. *ro- (Celtib., OIr., and OBret) vs. Lat. pro- and Sanskrit [Skt. ]pra-. ozas sues acc. pl. fem. 'six feet, unit of measure' (< *φodians < *pod-y-ans *sweks);

- aila 'stone building' < *pl̥-ya; cf. OIr. ail 'boulder'.

- vamos 'higher' < *uφamos < *up-m̥os.

- vrantiom 'remainder, rest' < *uper-n̥tiyo; cf. Lat. (s)uperans.

- Toponym Litania (now Ledaña) 'broad place' < *pl̥th2-ny-a.

However, it is possible that, as in other Celtic languages, *p before -l- was voiced to b, if the spelling of the place name 'konbouto (Roman Conplutum) represents /konblouto/.[10]

Final *-m is preserved in Celtiberian (and Lepontic), a further indication of these dialects' conservatism. It is generally fronted to -n in Gaulish (exceptional cases, for instance on the Larzac tablet, are probably due to influence from Latin): boustom "stable."[11]

Consonant clusters

- PIE *mn > un: as in Lepontic, Brythonic, and Gaulish, but not Old Irish and seemingly not Galatian. Kouneso 'neighbour' < *kom-ness-o < *kom-nedʰ-to; cf. OIr. comnessam 'neighbour' < *kom-nedʰ-t-m̥o.

- PIE *pn > un: Klounia < *kleun-y-a < *kleup-ni 'meadow'; cf. OIr. clúain 'meadow' < *klouni). However, in Latin, *pn > mn: damnum 'damage' < *dHp-no.

- PIE *pl > bl as in other Celtic languages, suggested by the placename konbouto (Roman Conplutum) if that represents /konblouto/.[12]

- PIE *nm > lm: Only in Celtiberian: melmu < *men-mōn 'intelligence', Melmanzos 'gifted with mind' < *men-mn̥-tyo; cf. OIr. menme 'mind' < *men-mn̥. Also occurs in modern Spanish: alma 'soul' < *anma < Lat. anima, Asturian galmu 'step' < Celt. *kang-mu.

- PIE *ps > *ss / s: usabituz 'he must excavate (lit. up/over-dig)' < *ups-ad-bʰiH-tōd, Useizu * < *useziu < *ups-ed-yō 'highest'. The Latin ethnic name contestani (Celtib. contesikum) recalls the proper name Komteso 'warm-hearted, friendly' < *kom-tep-so, cf. OIr. tess 'warm' > *tep-so. In Latin epigraphy, this sound is transcribed with gemination: Usseiticum 'of the Usseitici' < *Usseito < *upse-tyo. However, in Gaulish and Brythonic, *ps > *x; cf. Gaul. Uxama, MW uchel, 'one six'.

- PIE *pt > *tt / t: setantu 'seventh' < *septmo-to. However, in Gaulish and Insular Celtic, *pt > x: sextameto 'seventh', O.Ir. sechtmad (< *septmo-e-to).

- PIE *gs > *ks > *ss / s: sues 'six' < *sweks.

- Desobriga 'south/right-hand city' (Celts oriented themselves looking east) < *dekso-*bʰr̥ǵʰa; **Nertobris 'strong town' < *h₂ner-to-*bʰr̥ǵʰs.

- es- 'out of, not' < *eks < *h₁eǵʰs; cf. Lat. ex-, ComCelt. *exs-, OIr. ess-. In Latin epigraphy, this sound is transcribed with gemination: Suessatium < *sweks- 'sixth city'; cf. Lat. Sextantium.[13]

- Dessicae < *deks-ika. However, in Gaulish, *ks > *x: Dexivates.

- PIE *gt > *kt > *tt / t: ditas 'constructions, buildings' < *dʰigʰ-tas (= Lat. fictas).

- loutu 'load' < *louttu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu,

- litom 'it is permitted', ne-litom 'it is not permitted' < *l(e)ik-to; cf. Lat. licitum < *lik-e-to. However, in Common Celtic, *kt > *xt: luxtu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu; cf. OIr. lucht.

- Retugenos 'right-born, lawful' < *h₃reg-tō-genos, Gaul. Rextugenos. In Latin epigraphy, this sound is transcribed with gemination: Britto 'noble' < *brikto < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-to.

- Bruttius 'fruitful' < *bruktio < *bʰruHǵ-t-y-o; cf. Latin Fructuosus 'profitable'.

- PIE *st > *st: as opposed to Gaulish, Irish and Welsh, where the change was *st > ss. This preservation of the PIE cluster *st is another indication of the phonological conservatism of Celtiberian. Gustunos 'excellent' < *gustu 'excellence' < *gus-tu; cf. OIr. gussu 'excellence', Fergus < *viro-gussu, Gaul. gussu (Lezoux Plate, line 7).

Vowels

- PIE *e, *h₁e > e:

- Togoitei eni 'in Togotis' < *h₁en-i; cf. Lat. in, OIr. in 'into, in'.

- somei eni touzei 'inside this territory'.

- es- 'out of, not' < *eks < *h₁eǵʰs; cf. Lat. ex-, ComCelt. *exs-, OIr. ess-.

- esankios 'not enclosed, open', lit. 'unfenced' < *h₁eǵʰs-*h₂enk-yos.

- treba 'settlement, town'; Kontrebia 'conventus, capital' < *kom-treb-ya; cf. OIr. treb, W. tref 'settlement'.

- ekuo horse < *h₁ekw-os, ekualo 'horseman'.

- PIE *h₂e > a:

- ankios 'fenced, enclosed' < *h₂enk-yos.

- Ablu 'strong' < *h₂ep-lō 'strength'.

- augu 'valid, firm' < *h₂ewg-u, adj. 'strong, firm, valid'.

- PIE *o, *Ho > o:

- olzui (dat.sing.) 'for the last' < *olzo 'last' < *h₂ol-tyo, cf. Lat. ultimus < *h₂ol-t-m̥o, OIr. ollam 'master poet' < *oltamo < *h₂ol-t-m̥).

- okris 'mountain' < *h₂ok-r-i; cf. Lat. ocris 'mountain', OIr. ochair 'edge' < *h₂ok-r-i.

- monima 'memory' < *monī-mā < *mon-eye-mā.

- PIE *eh₁ > ē > ī?. This Celtic reflex isn't well attested in Celtiberian. e.g. IE *h₃rēg'-s meaning "king, ruler" vs. Celtiberian -reiKis, Gaulish -rix, British rix, Old Irish rí, Old Welsh, Old Breton ri meaning "king". In any case, the maintenance of PIE ē = ē is well attested in dekez 'he did' < *deked < *dʰeh₁k-et, identical to Latin fecit.

- PIE *eh₂ > ā:

- dāunei 'to burn' < *deh₂u-nei; cf. OIr. dóud, dód 'burn' < *deh₂u-to-.

- silabur sāzom 'enough money, a considerable amount of money' < *sātio < *seh₂t-yo, ComCelt. *sāti 'sufficiency', cf. OIr. sáith.

- kār 'friendship' < *keh₂r; cf. Lat. cārus 'dear' < *keh₂r-os, Ir. cara 'friend', W. caru 'love' < *kh₂r-os.

- PIE *eh₃, *oH > a/u: Celt. *ū in final syllables, *ā in non-final syllables; e.g.:

- datuz 'he must give' < *dh₃-tōd.

- dama 'sentence' < *dʰoh₁m-eh₂ 'put, dispose'; cf. OIr. dán 'gift, skill, poem', Germanic dōma < *dʰoh₁m-o 'verdict, sentence'.

- PIE *Hw- > w-: uta 'conj. and, prep. besides' < *h₂w-ta, 'or, and'; cf. Umb. ute 'or', Lat. aut 'or' < *h₂ew-ti.

- PIE ey remains ey in Celtiberian and Lepontic, especially in root syllables (teiuo- < *dēywo- 'god', ueido- probably 'witness' < *weyd- 'see'). In other Celtic languages, it becomes ē (another indication of Celtiberian conservatism, unless these spellings indicate a high /e/ rather than an actual diphthong). In final syllables, there is some variation in the spelling, with some datives preserving the diphthong:Togoitei eni 'in Togotis', somei eni touzei 'inside of this territory'; and others, not: GENTE (K.11.1) with NSg. kentis/gentis (K.1.3), STENIONTE (K.11.1).[14][15]

Syllabic resonants and laryngeals

- PIE *n̥ > an / *m̥ > am:

- arganto 'silver' < *h₂r̥gn̥to; cf. OIr. argat, OW argant, Lat. argentum.

- kamanom 'path, way' *kanmano < *kn̥gs-mn̥-o; cf. OIr. céimm, OW cemmein 'step'.

- decameta 'tithe' < *dekm̥-et-a; cf. Gaul. decametos, OIr. dechmad 'tenth'.

- dekam 'ten' (cf. Lat. decem, ComCelt. dekam, OIr. deich < *dekm̥.

- novantutas 'the nine tribes' > novan 'nine' < *h₁newn̥; cf. Lat. novem, ComCelt. *novan, OW nauou.

- ās 'we, us' < *ans < *n̥s, OIr. sinni < *sisni, *snisni 'we, us', cf. German uns < *n̥s.

- trikanta < *tri-kn̥g-ta, lit. 'three horns, three boundaries' > 'civil parish, shire' (modern Spanish Tres Cantos).

- PIE *CHC > CaC (C = any consonant, H = any laryngeal), as in Common Celtic and Italic (SCHRIJVER 1991: 415, McCONE 1996: 51 and SCHUMACHER 2004: 135):

- datuz < *dh₃-tōd, dakot 'they put' < *dʰh₁k-ont,

- matus 'propitious days' < *mh₂-tu; cf. Lat. mānus 'good' < *meh₂-no, OIr. maith 'good' < *mh₂-ti.

- PIE *CCH > CaC (C = any consonant, H = any laryngeal): Magilo 'prince' < *mgh₂-i-lo; cf. OIr. mál 'prince' < *mgh₂-lo.

- PIE *r̥R > arR and *l̥R > alR (R = resonant): arznā 'part, share' < *φarsna < *parsna < *pr̥s-nh₂; ComCelt. *φrasna < *prasna < *pr̥s-nh₂; cf. OIr. ernáil 'part, share'.

- PIE *r̥P > riP and *l̥P > liP (P = plosive):

- briganti PiRiKanTi < *bʰr̥ǵʰ-n̥ti 'high, elevated ones'.

- silabur konsklitom 'silver coined' < *kom-skl̥-to 'to cut'.

- PIE *Cr̥HV > CarV and *Cl̥HV > CalV:

- sailo 'dung, slurry' *salyo < *sl̥H-yo; cf. Lat. saliva < *sl̥H-iwa, OIr. sal 'dirt' < *sl̥H-a.

- aila 'stone building' < *pl̥-ya; cf. OIr. ail 'boulder'.

- are- 'first, before'; cf. OIr. ar 'for', Gaul. are 'in front of', < *pr̥h₂i and Lat. prae- 'before' < *preh₂i.

- PIE *HR̥C > aRC (H = any laringeal, R̥ any syllabic resonant, C = any consonant, as in Common Celtic (JOSEPH 1982: 51 and ZAIR 2012: 37): arganto 'silver' < *h₂r̥gn̥to, not **riganto.

Exclusive developments

Affrication of the PIE groups -*dy-, -*dʰy-. -*ty- > z/th (/θ/) between vowels and of -*d, -*dʰ > z/th (/θ/) at the ends of words:

- adiza 'duty' < *adittia < *h₂ed-d(e)ik-t-ya.

- Useizu 'highest' < *ups-ed-yō.

- touzu 'territory' < *teut-yō.

- rouzu 'red' < *reudʰy-ō.

- olzo 'last' < *h₂ol-tyo.

- ozas 'feet' < *pod-y-ans.

- datuz < *dh₃-tōd; louzu 'free' (in: LOUZOKUM, MLH IV, K.1.1.) < *h₁leudʰy-ō; cf. Oscan loufir 'free man', Russian ljúdi 'men, people'.

That this is one of only a very few phonological developments that distinguishes Celtiberian phonologically from Proto-Celtic is one reason Matasovic has deemed Celtiberian a very early independent branch of Proto-Celtic.[16] It is noteworthy that this weakening of most non-initial Proto-Celtic voiced dental stops (ds) seems to indicate that Celtiberian had taken the first step in what became more-widespread lenition of non-initial (and in some cases even initial) voiced consonants in later Celtic dialects.[17]

Remove ads

Morphology

Summarize

Perspective

Noun and adjective cases

- arznā 'part, share' < *parsna < *pr̥s-nh₂. ComCelt. *φrasna < *parsna.

- veizos 'witness' < *weidʰ-yo < *weidʰ- 'perceive, see' / vamos 'higher' < *up-m̥os.

- gentis 'son, descent' < *gen-ti. ComCelt. *genos 'family'.

- loutu 'load' < *louttu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu. ComCelt. *luxtu < *louktu < *leugʰ-tu; cf. OIr. lucht.

- duater 'daughter' < *dʰugh₂tēr. ComCelt. *duxtir.

An -n- stem can be seen in melmu nom. sg. < *-ōn, melmunos gen. sg. (from Botorrita III, probably a name).

STENIONTE (a name) (K.11.1) is probably the dative of an -nt- stem.[23]

It is notable that the genitive singular -o- stem ends in -o in Celtiberian, unlike the rest of Celtic (and Latin), where this ending is -ī [24][25]

There is also a potential vocative case, but it is very poorly attested, with only an ambiguous -e ending for o-stem nouns cited in the literature.

Demonstrative pronouns

Relative pronoun

Forms of the masculine singular relative pronoun *yo- can be found in the first Botorrita plaque: The form io-s in line 10 is the nominative singular masculine of the relative pronoun from PIE *yo- (Skt. ya-, Greek hos), which shows up in Old Irish only as the origin of leniting relative verb forms (the OIr endingless nominative form *yo providing the intervocalic context for lenition) and the nasalizing relative forms (from the accusative *yo-m).[27] Line 7 has the accusative singular io-m and the dative singular io-mui (<*yo-sm-ōi; cf. Skt. yasmai) from the same root.[28][29]

Verbal endings

The PIE third-person verbal ending system seems to be evident, though the exact meaning of many verbs remains unclear:

- primary singular active *-ti in ambitise-ti (Botorrita I, A.5), '(that someone) builds around > encloses' from *h₂m̥bhi-dʰingʰ-s-e-ti.

- auzeti, secondary *-t > /θ/ written <z> in terbere-z (SP.02.08, B-4) and perhaps kombalke-z.

- primary plural active *-nti in ara-nti (Z.09.24, A-4) and zizonti 'they sow' (or perhaps 'they give', with assimilation of the initial to the medial <z>).[30]

- secondary *-nt perhaps in atibio-n (Z.09.24, A-5).

- middle voice *-nto in auzanto (Z.09.03, 01) and perhaps esianto (SP.02.08 A-2).[31]

A third-person imperative *-tо̄d > -tuz perhaps is seen in da-tuz 'he must give' (bronze plaque of Torrijo del Campo), usabituz, bize-tuz (Botorrita I A.5) and dinbituz 'he must build' < *dʰingʰ-bī-tōd.

A possible third-person singular subjunctive -a-ti may be asekati, and another in -e-ti may be seen in auzeti < *aw-dhh1-e-ti 'he may bestow.'[31]

From the same root may come a truncated form of an athematic active third-person singular aorist, if auz is from *auzaz < *aw-dhh1-t.[31]

Also from the same root, an example of the genitive plural of the present active participle ending -nt-om may be found on the Novallas bronze tablet in audintum < *awdheh1-nt-ōm.[31]

Possible infinitive form -u-nei, perhaps from *-mn-ei, may be seen in ambi-tinko-unei (Botorrita I A.5) and ta-unei ‘to give’,[30][24] a reduplicated infinitive form in ti-za-unei > *dhi-dhh1-mn-ei "to place."[32] It is notable that no infinitive forms were preserved or developed in the insular Celtic languages.[33]

Remove ads

Syntax

Celtiberian syntax is considered to have the basic order subject–object–verb.[34] Another archaic IE feature is the use of the relative pronoun jos and the repetition of enclitised conjunctions such as kwe.

Sample texts

Summarize

Perspective

First Botorrita plaque, side A

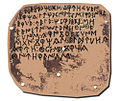

One of four bronze plaques found in Botorrita, this text was written in eastern Celtiberian script. The other side consists of a list of names. (K.01.01.A)

- trikantam : bergunetakam : togoitos-kue : sarnikio (:) kue : sua : kombalkez : nelitom

- nekue [: to-ver-daunei : litom : nekue : daunei : litom : nekue : masnai : dizaunei : litom : soz : augu

- aresta[lo] : damai : uta : oskues : stena : verzoniti : silabur : sleitom : konsklitom : gabizeti

- kantom [:] sanklistara : otanaum : togoitei : eni : uta : oskuez : boustom-ve : korvinom-ve

- makasiam-ve : ailam-ve : ambidiseti : kamanom : usabituz : ozas : sues : sailo : kusta : bizetuz : iom

- asekati : [a]mbidingounei : stena : es : vertai : entara : tiris : matus : dinbituz : neito : trikantam

- eni : oisatuz : iomui : listas : titas : zizonti : somui : iom : arznas : bionti : iom : kustaikos

- arznas : kuati : ias : ozias : vertatosue : temeiue : robiseti : saum : dekametinas : datuz : somei

- eni touzei : iste : ankios : iste : esankios : uze : areitena : sarnikiei : akainakubos

- nebintor : togoitei : ios : vramtiom-ve : auzeti : aratim-ve : dekametam : datuz : iom : togoitos-kue

- sarnikio-kue : aiuizas : kombalkores : aleites : iste : ires : ruzimuz : Ablu : ubokum

- soz augu arestalo damai[35]

- all this (is) valid by order of the competent authority

- soz: all this (< *sod).

- augo: final, valid (< *h₂eug-os 'strong, valid', cf. Latin augustus 'solemn').

- arestalo: of the competent authority (gen. sing. arestalos < *pr̥Hi-steh₂-lo 'competent authority' < *pr̥Hi-sto 'what is first, authority').

- damai: by order (instrumental fem. sing. < *dʰoh₁m-eh₂ 'establish, dispose').

- (Translation: Prospér 2006)

- saum dekametinas datuz somei eni touzei iste ankios iste es-ankios[36]

- of these, he will give the tax inside of this territory, so be fenced as be unfenced

- saum: of these (< *sa-ōm).

- dekametinas: the tithes, the tax.

- datuz: he will pay, will give.

- eni: inside, in (< *h₁en-i).

- somei: of this (loc. sing. < *so-sm-ei 'from this').

- touzei: territory (loc. sing. < *touzom 'territory' < *tewt-yo).

- iste ankios: so (be) fenced.

- iste es-ankios: as (be) unfenced.

- (Transcription: Jordán 2004)

- togoitei ios vramtiom-ve auzeti aratim-ve dekametam datuz

- In Togotis, he who draws water either for the green or for the farmland, the tithe (of their yield) he shall give

- (Translation: De Bernardo 2007)

Great inscription from Peñalba de Villastar

An inscription in the Latin alphabet in the Celtiberian sanctuary of Peñalba de Villastar, in the current municipality of Villastar, Teruel province. (K.03.03) Other translations, which differ dramatically from this and from each other, may be found in P. Sims-Williams' treatment of the Celtic languages in The Indo-European Languages.[37]

- eni Orosei

- uta Tigino tiatunei

- erecaias to Luguei

- araianom komeimu

- eni Orosei Ekuoisui-kue

- okris olokas togias sistat Luguei tiaso

- togias

- eni Orosei uta Tigino tiatunei erecaias to Luguei araianom comeimu

- In Orosis and the surroundings of Tigino river, we dedicate the fields to Lugus.

- eni: in (< *h₁en-i).

- Orosei: Orosis (loc. sing. *oros-ei).

- uta: and (conj. cop.).

- Tigino: of Tigino (river) (gen. sing. *tigin-o).

- tiatunei: in the surroundings (loc. sing. *tiatoun-ei < *to-yh₂eto-mn-ei).

- erecaias: the furrows > the land cultivated (acc. pl. fem. erekaiās < *perka-i-ans > English furrow).

- to Luguei: to Lugus.

- araianom: properly, totally, (may be a verbal complement > *pare-yanom, cfr. welsh iawn).

- comeimu: we dedicate (present 3 p.pl. komeimu < *komeimuz < *kom-ei-mos-i).

- eni Orosei Ekuoisui-kue okris olokas togias sistat Luguei

- In Orosis and Equeiso the hills, the vegetable gardens [and] the houses are dedicated to Lugus.

- Ekuoisui: in Ekuoisu (loc. sing.) -kue: and (< *-kʷe).

- okris: the hills (nom. pl. < *h₂ok-r-eyes).

- olokas: the vegetable gardens (nom. pl. olokas < *olkās < *polk-eh₂-s > English fallow).

- togias: (and) the roofs > houses (nom. pl. or gen. sg. togias < tog-ya-s > Old Irish tuige "cover, protection").[38]

- sistat: are they (dedicated) (3 p.pl. < *sistant < *si-sth₂-nti).

- Luguei: to Lug (dat. Lugue-i).

- (Transcription: Meid 1994, Translation: Prósper 2002[39])

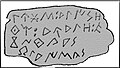

Bronze plaque of Torrijo del Campo

A bronze plaque found in Torrijo del Campo, Teruel province in 1996, using the eastern Celtiberian script.

- kelaunikui

- derkininei : es

- kenim : dures : lau

- ni : olzui : obakai

- eskenim : dures

- useizunos : gorzo

- nei : lutorikum : ei

- subos : adizai : ekue : kar

- tinokum : ekue : lankikum

- ekue : tirtokum : silabur

- sazom : ibos : esatui

- Lutorikum eisubos adizai ekue Kartinokum ekue Lankikum ekue Tirtokum silabur sazom ibos esatui (datuz)

- for those of the Lutorici included in the duty, and also of the Cartinoci, of the Lancici and of the Tritoci, must give enough money to settle the debt with them.

- Lutorikum: of the Lutorici ( gen. masc. pl.).

- eisubos: for those included ( < *h1epi-s-o-bʰos).

- adizai: in the assignment, in the duty (loc. fem. sing. < *adittia < *ad-dik-tia. Cfr. Latin addictio 'assignment').

- ekue: and also (< *h₂et(i)kʷe).

- Kartinokum: of the Cartinoci ( gen. masc. pl.).

- Lankikum: of the Lancici ( gen. masc. pl.).

- Tirtokum: of the Tritoci ( gen. masc. pl.).

- silabur: money.

- sazom: enough (< *sātio < *seh₂t-yo).

- ibos: for them (dat.3 p.pl. ibus < *i-bʰos).

- esatui: to settle the debt (< *essato < *eks-h₂eg-to. Cfr. Latin ex-igo 'demand, require' & exactum 'identical, equivalent').

- datuz: must give (< *dh₃-tōd).

- (Transcription and Translation: Prósper 2015)

- Cortono plaque. Unknown origin.

- Fröhner tessera. Unknown origin.

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

Further reading

- Overview

- Beltrán Lloris, Francisco; Jordán Cólera, Carlos. "Celtibérico". In: Palaeohispanica: revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania antigua n. 20 (2020): pp. 631–688. ISSN 1578-5386 DOI: 10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.395

- de Bernardo Stempel, Patrizia (2002). "Centro Y áreas Laterales: Formación Del Celtibérico Sobre El Fondo Del Celta Peninsular Hispano". In: Palaeohispanica. Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua, n.º 2 (diciembre), 89-132. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i2.349.

- Blažek, Václav. "Celtiberian". In: Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity. N, Řada klasická = Graeco-Latina Brunensia. 2007, vol. 56, iss. N. 12, pp. [5]-25. ISSN 1211-6335.

- Jordán Cólera, Carlos (2007). "Celtiberian". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. Vol. 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula. Article 17. pp. 749–850. ISSN 1540-4889 Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol6/iss1/17

- Lexicon

- Bernardo Stempel, Patrizia de. "Celtic ‘son’, ‘daughter’, other descendants, and *sunus in Early Celtic". In: Indogermanische Forschungen 118, 2013 (2013): 259–298. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/indo.2013.118.2013.259

- Fernández, Esteban Ngomo. “A propósito de matrubos y los términos de parentesco en celtibérico”. In: Boletín del Archivo Epigráfico. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. nº. 4 (2019): 5-15. ISSN 2603-9117

- Fernández, Esteban Ngomo. "El color rojo en celtibérico: del IE *H1roudh- al celtibérico routaikina". In: Boletín del Archivo Epigráfico. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. nº. 6 (junio, 2020): 5-19. ISSN 2603-9117

- Stifter, David (2006). "Contributions to Celtiberian Etymology II". In: Palaeohispanica: revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania Antigua, 6. pp. 237–245. ISSN 1578-5386.

- Wodtko, Dagmar (2023). "Das Keltiberische Lexikon" [The Celtiberian lexicon]. Palaeohispanica. Revista Sobre Lenguas y Culturas de la Hispania Antigua (in German). 23 (23): 151–64. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v23i0.531.

- Alphabet

- Jordán Cólera, Carlos (2015). "La valeur du s diacrité dans les inscriptions celtibères en alphabet latin". Études Celtiques (in French). 41: 75–94. doi:10.3406/ecelt.2015.2450.

- Simón Cornago, Ignacio; Jordán Cólera, Carlos Benjamín. "The Celtiberian S. A New Sign in (Paleo)Hispanic Epigraphy". In: Tyche 33 (2018). pp. 183–205. ISSN 1010-9161

Remove ads

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads